In enterprise applications, nearly every request is executed within a database transaction.

Developers often use frameworks and libraries with declarative mechanisms to simplify transaction management.

The Spring framework, for example, uses a special annotation to arrange for method invocations to be automatically executed within a transaction. This annotation simplifies writing transactional business logic, making it easier to manage transactions in a monolithic application that accesses a single database.

However, while transaction management is relatively straightforward in a monolithic application accessing a single database, it becomes more complex in scenarios involving multiple databases and message brokers.

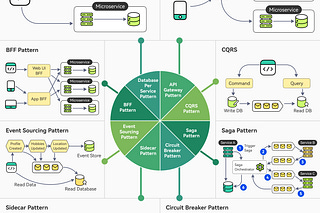

For example, in a microservice architecture, business transactions span multiple services, each with its database. This complexity makes the traditional transaction approach impractical. Instead, microservices-based applications must adopt alternative mechanisms to manage transactions effectively.

In this post, we’ll learn why microservices-based applications require a more sophisticated approach to transaction management, such as using the Saga pattern. We’ll also understand the different approaches to implementing the Saga pattern in an application.

The Need for Saga Pattern

Business transactions can be significantly more complex than traditional database transactions.

To understand this complexity, let's consider a real-world example of placing an order on an e-commerce platform.

From the moment the user clicks the "Buy" button to the point where the product is delivered to the user’s doorstep, a series of steps takes place, forming a complete business transaction.

Here are the key steps involved:

Placing an Order: The user selects the desired products, adds them to the cart, and initiates the checkout process. This step involves capturing the order details, such as the items, quantities, and shipping address.

Creating an Invoice: Once the order is placed, an invoice is generated. The invoice serves as a record of the transaction and is used for billing and accounting purposes.

Handling Payments: The payment process is initiated, where the user provides their payment information, such as credit card details. The payment is processed securely, and upon successful completion, the order is confirmed.

Shipping the Product: After the payment is processed, the order is prepared for shipping. Tracking information is generated, and the user is notified of the estimated delivery date.

Implementing this logic in a monolithic application with a single database is relatively straightforward since all the data required is accessible from a single database.

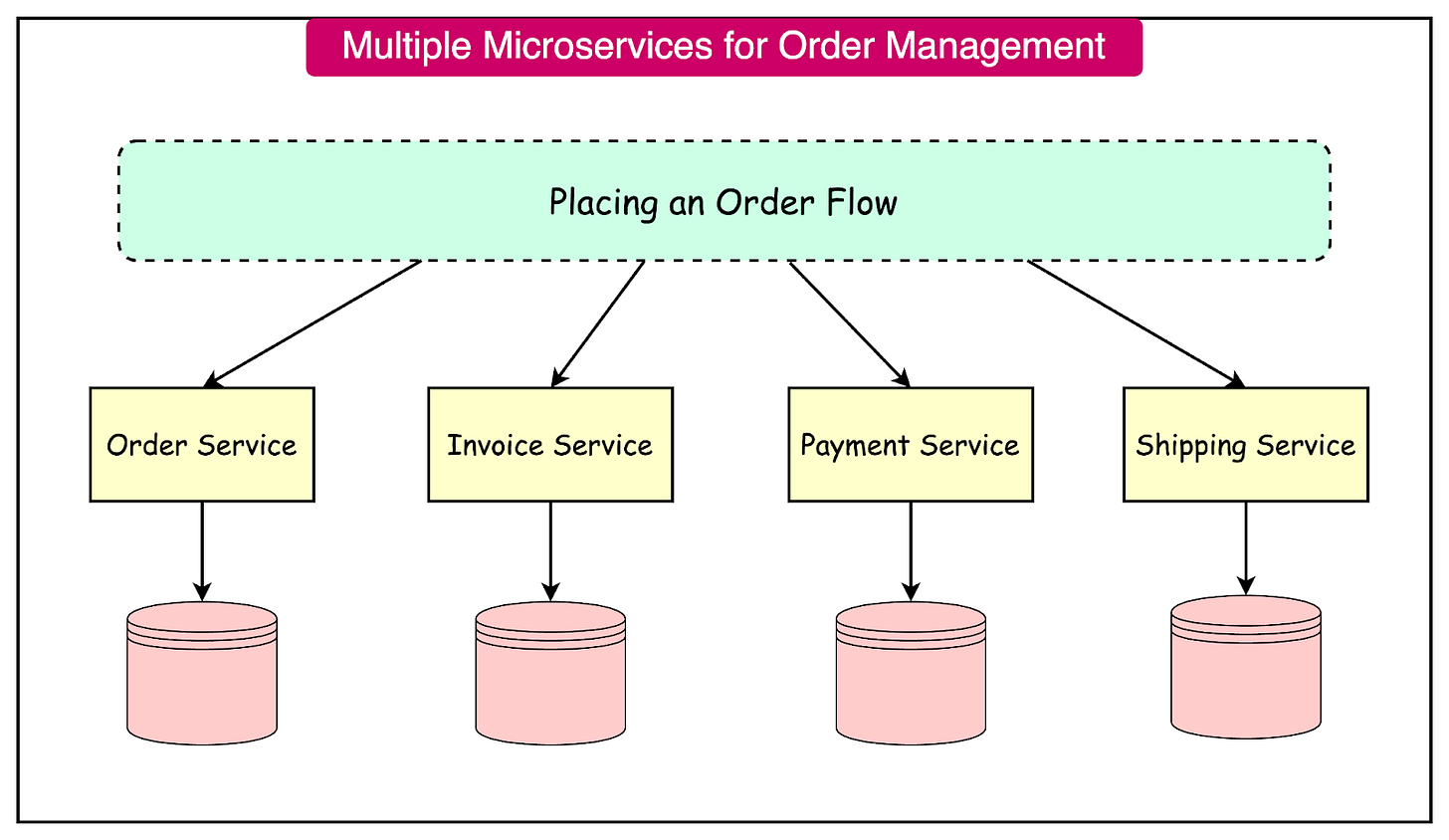

In contrast, implementing the same in a microservice architecture is much more complicated. In microservices, the needed data is scattered across multiple services.

Here’s one possible arrangement of the various microservices that may be involved.

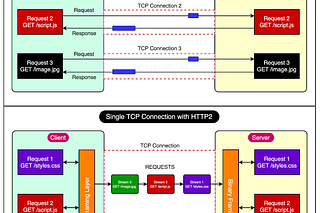

The traditional approach to maintaining data consistency across multiple services, databases, or message brokers involves distributed transactions.

The X/Open Distributed Transaction Processing (DTP) Model, specifically the XA protocol, is the de facto standard for managing these transactions. XA uses a two-phase commit (2PC) mechanism to ensure that all participants in a transaction either commit or rollback uniformly.

However, despite the simplicity, the use of distributed transactions in a heterogeneous environment poses several challenges:

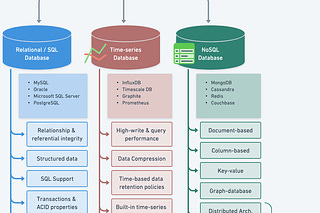

Limited Technology Support: Many modern technologies, such as NoSQL databases like MongoDB and Cassandra, do not support distributed transactions. Similarly, modern message brokers like RabbitMQ and Apache Kafka do not support this type of transaction. This limitation restricts the choice of technologies that can be used in systems requiring distributed transactions.

Availability Concerns: Distributed transactions are a form of synchronous inter-process communication (IPC), which can significantly reduce system availability. For a distributed transaction to commit, all participating services must be available. The overall availability of the system is the product of the availability of all participants in the transaction.

In modern application development, an alternative approach using event-driven architecture and Saga pattern is often preferred for managing complex business transactions. This approach offers better scalability, higher availability, and greater flexibility.

The Saga Pattern

A Saga is a sequence of local transactions, each updating data within a single service using familiar ACID transaction frameworks and libraries. Here’s how it works:

Initiation of the Saga: The system operation initiates the first step of the saga.

Local Transactions: Each local transaction completes and triggers the execution of the next local transaction in the sequence.

Messaging and Loose Coupling: When a local transaction is completed, the service publishes a message that triggers the next step in the saga. This messaging approach ensures that the Saga participants are loosely coupled, enhancing the overall flexibility and reliability of the system.

Sagas differ from traditional ACID transactions in several important ways:

Lack of Isolation: Unlike ACID transactions, Sagas do not provide the isolation property. This means that intermediate states of the Saga may be visible to other services or users.

Messaging and Buffering: The use of messaging ensures that the saga is completed even if the recipient of a message is temporarily unavailable. Message brokers buffer messages until they can be delivered, guaranteeing that the saga progresses as intended.

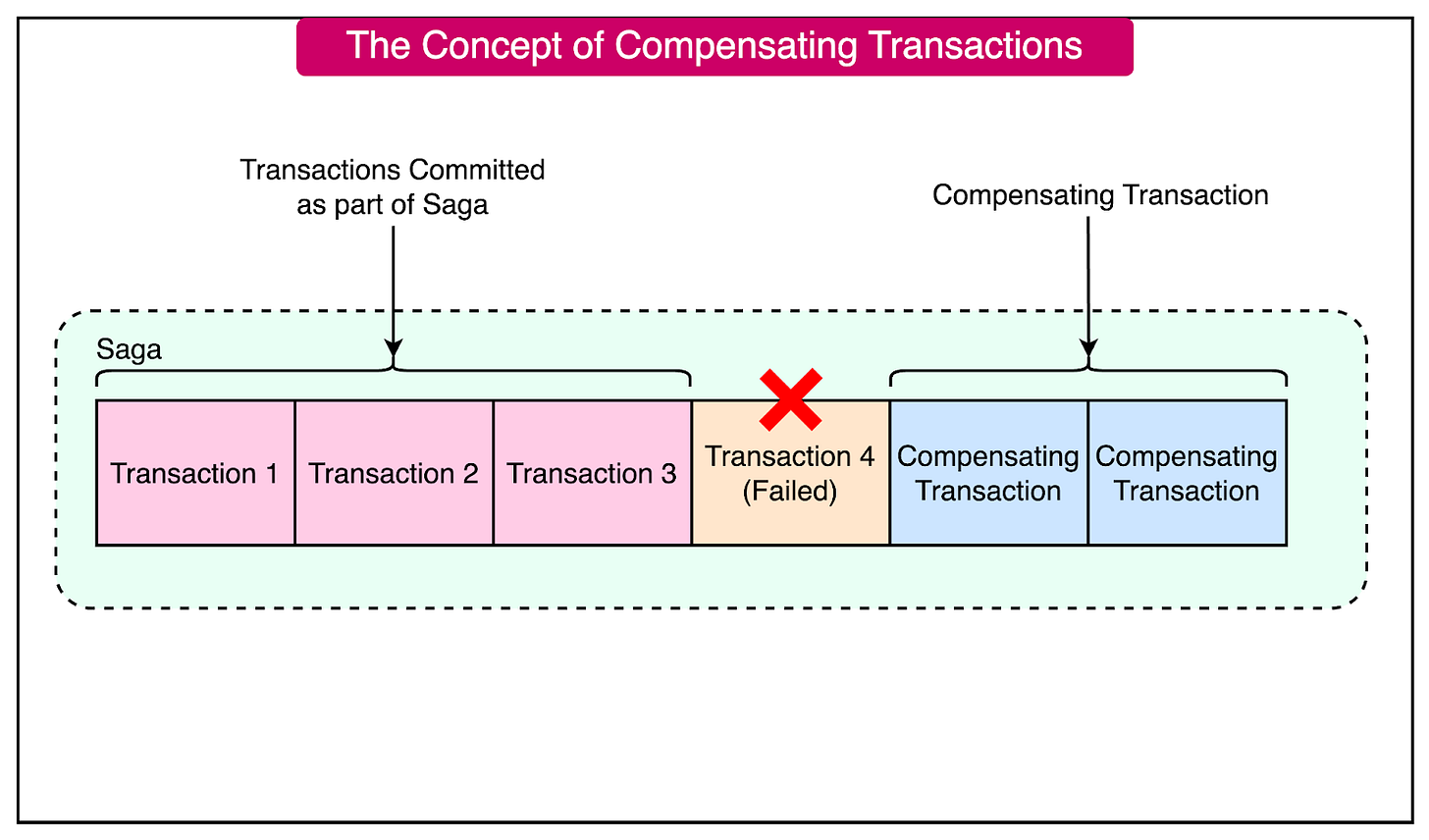

One of the significant differences between sagas and traditional ACID transactions is the handling of rollbacks.

In ACID transactions, if a business rule violation is detected, the transaction can be easily rolled back using a ROLLBACK statement, undoing all changes made so far.

However, in Sagas, each step commits its changes to the local database, making automatic rollback impossible. If a local transaction fails or a business rule is violated, the application must explicitly undo the changes made by previous steps. This is achieved through compensating transactions. Compensating transactions are executed in reverse order of the forward transactions to ensure that the system returns to a consistent state.

See the diagram below:

To illustrate this concept, consider a Create Order saga:

Step 1: Place Order - The order service creates an order and publishes a message.

Step 2: Validate Order - The validation service checks the order details and publishes a message.

Step 3: Process Payment - The payment service processes the payment and publishes a message.

Step 4: Authorize Credit Card - If the credit card authorization fails, compensating transactions must be executed to undo the changes made by the previous steps. This means that the Order status should be changed to something like REJECTED and the customer is notified.

Let us now look at two different styles to implement the Saga pattern.

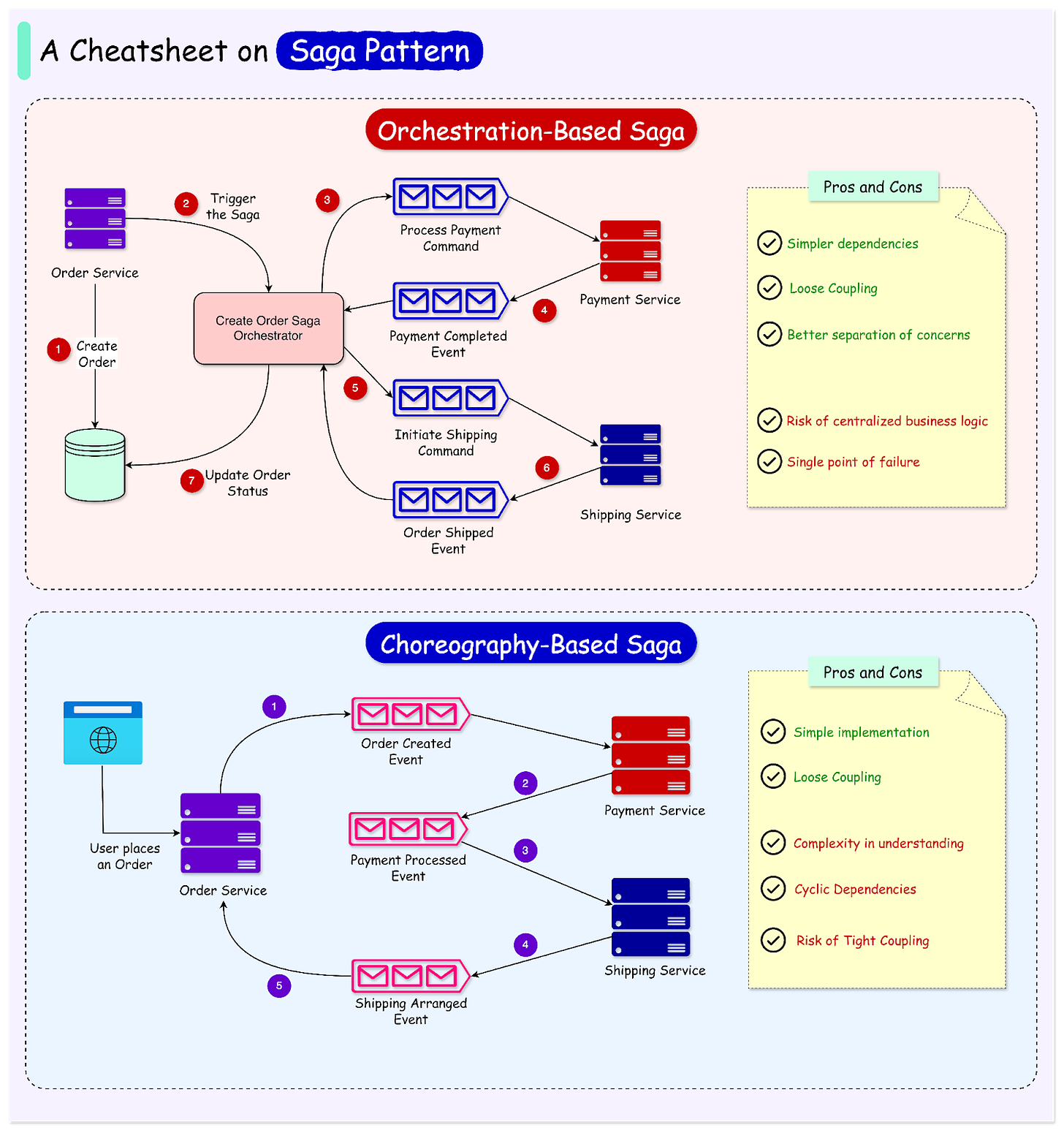

Orchestration-based Saga

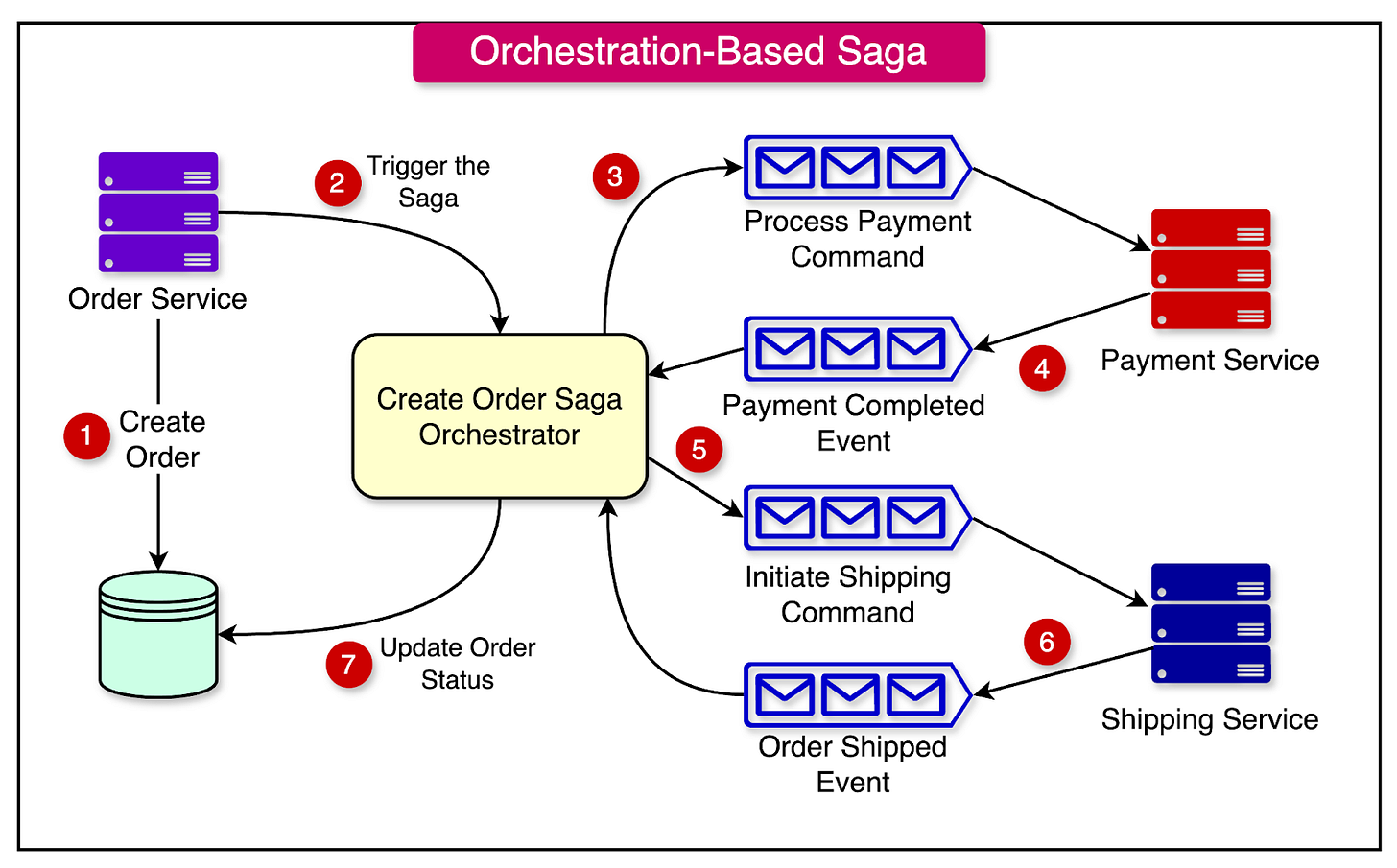

In an Orchestration-based Saga, the orchestrator communicates with the participants by sending command messages that specify the operations to be performed. After a participant completes an operation, it sends a reply message back to the orchestrator. The orchestrator then processes this message and determines the next step in the Saga workflow.

Some key characteristics of orchestration-based Sagas are as follows:

Centralized Workflow Definition: The orchestrator explicitly defines the Saga's workflow, specifying the sequence of steps and their dependencies. This centralized approach makes it easier to visualize and reason about the overall process, as the logic is encapsulated within the orchestrator.

Command/Async Reply Interaction: The orchestrator uses command messages to instruct participants on which operations to perform. Participants respond with reply messages, allowing the orchestrator to proceed with the next step in the workflow.

To understand the orchestration approach better, let's consider an example of an order processing system. The order processing involves multiple steps:

Placing the Order: The user selects the desired products, adds them to the cart, and initiates the checkout process.

Validating the Order: The order details are validated to ensure correctness and completeness.

Processing the Payment: The payment is processed securely, and upon successful completion, the order is confirmed.

Shipping the Order: The order is prepared for shipping, and tracking information is generated.

The orchestrator would manage these steps as follows:

Triggering the Order Placement: The Order Service creates a new order with PENDING status and triggers the Create Order Saga Orchestrator.

Order Validation: Once the order is placed, the orchestrator triggers the order validation step. If the validation succeeds, it proceeds to the next step.

Payment Processing: After successful validation, the orchestrator initiates the payment processing step by calling the Payment Service.

Shipping the Order: Once the payment is completed, the orchestrator triggers the shipping process by calling the Shipping Service to deliver the order to the customer.

Order Status Update: After the order is shipped, the orchestrator updates the order status.

See the diagram below for an example of the orchestration-based Saga.

In an orchestration-based Saga, individual steps can involve a service updating a database and publishing a message. For instance, the Order Service might persist an order and then send a message to the next Saga participant. To ensure atomicity, services must use transactional messaging to update the database and publish messages simultaneously.

If any step in the Saga fails, the orchestrator handles the failure by initiating compensating actions to roll back the previous steps and maintain data consistency. This ensures that the system remains in a consistent state even in the face of failures.

Benefits of Orchestration-based Sagas

Orchestration-based Sagas offer several benefits that enhance the design and operation of complex business transactions:

Simpler Dependencies: One significant advantage of orchestration is that it avoids cyclic dependencies. The Saga orchestrator invokes the Saga participants, but the participants do not invoke the orchestrator. This one-way dependency ensures that there are no cyclic dependencies, simplifying the overall architecture.

Loose Coupling: Each service implements an API that is invoked by the orchestrator, eliminating the need for services to know about the events published by other Saga participants. This loose coupling enhances the modularity and flexibility of the system.

Improved Separation of Concerns: The Saga coordination logic is localized within the Saga orchestrator. This separation of concerns simplifies the business logic within domain objects, as they do not need to be aware of the Sagas they participate in. For example, during the execution of the Create Order Saga, the Order can transition directly from the PENDING state to the APPROVED state without intermediate states corresponding to the Saga steps. This simplifies the state machine model of the Order class, making the business logic more straightforward.

Drawbacks of Orchestration-based Sagas

While Orchestration-based Sagas offer several benefits, they also have a notable drawback:

Risk of Centralizing Business Logic: There is a risk of centralizing too much business logic within the orchestrator, leading to a design where the smart orchestrator tells the dumb services what operations to perform. However, this issue can be mitigated by designing orchestrators that are solely responsible for sequencing the steps and do not contain any additional business logic.

Choreography-based Saga

In a Choreography-based Saga, each service involved in the Saga communicates directly with others by publishing events. Unlike orchestration, which relies on a central coordinator, Choreography-based Saga empowers services to make decisions and react to events independently.

When a service performs an action or encounters a notable condition within its domain, it publishes an event to notify other services. This event contains relevant information about the action or condition, allowing other services to react accordingly.

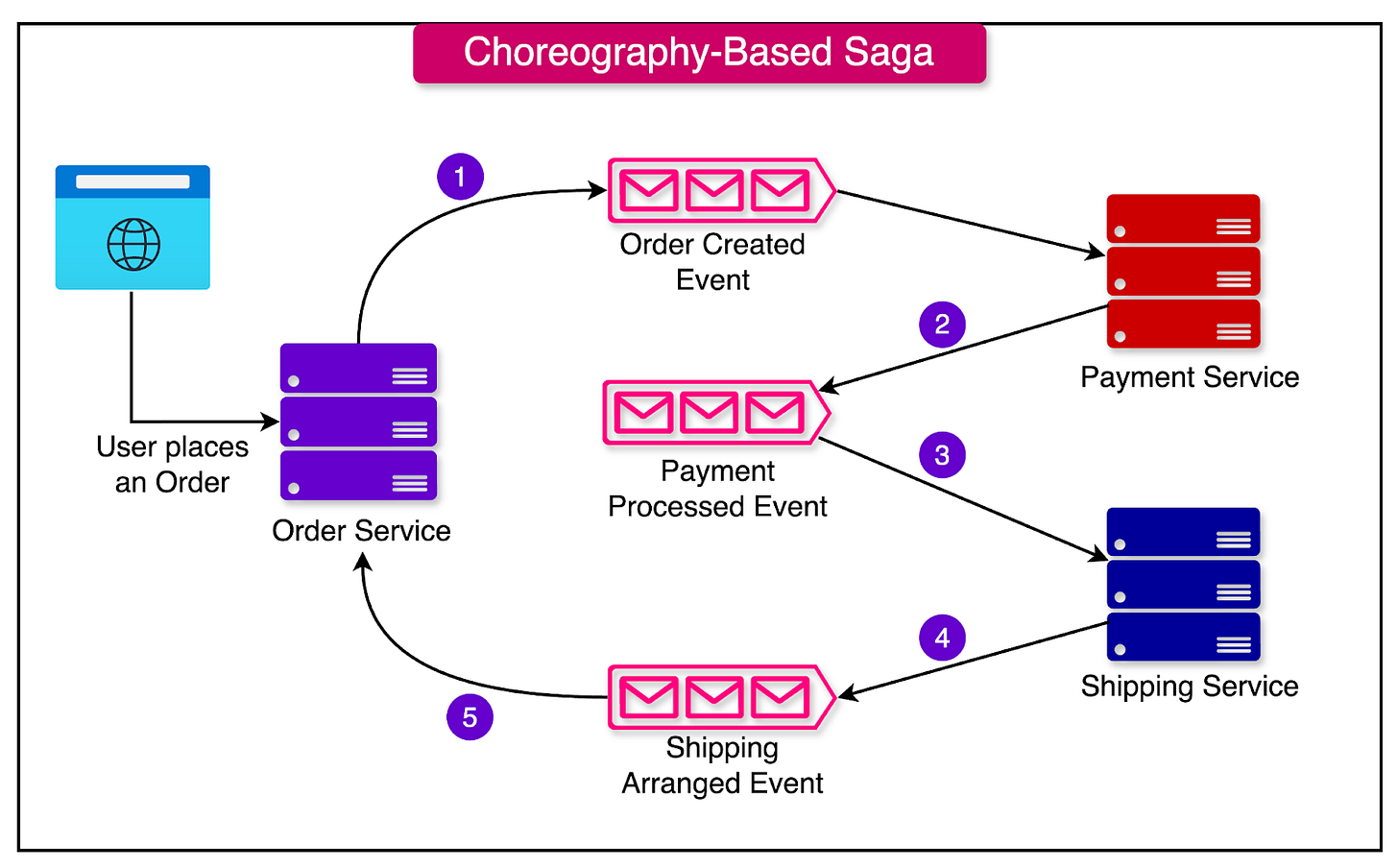

Here’s a detailed example using an order processing scenario:

Order Service: Receives a new order request and creates an order. It publishes an "OrderCreated" event.

Payment Service: Listens for the "OrderCreated" event and initiates payment processing. If the payment is successful, it publishes a "PaymentSucceeded" event. If the payment fails, it publishes a "PaymentFailed" event.

Shipping Service: Listens for the "Payment Processed" event and arranges for the order's shipping. It publishes a "ShippingArranged" event.

If any service encounters an error or receives a compensating event (e.g., "PaymentFailed" or "InventoryUnavailable"), it performs the necessary compensating actions. For example, if the Payment Service receives a "PaymentFailed" event, it cancels the order and publishes an "OrderCancelled" event.

See the diagram below to understand the choreography-based flow:

When implementing choreography-based Sagas, there are several key considerations to ensure reliable and efficient communication between services:

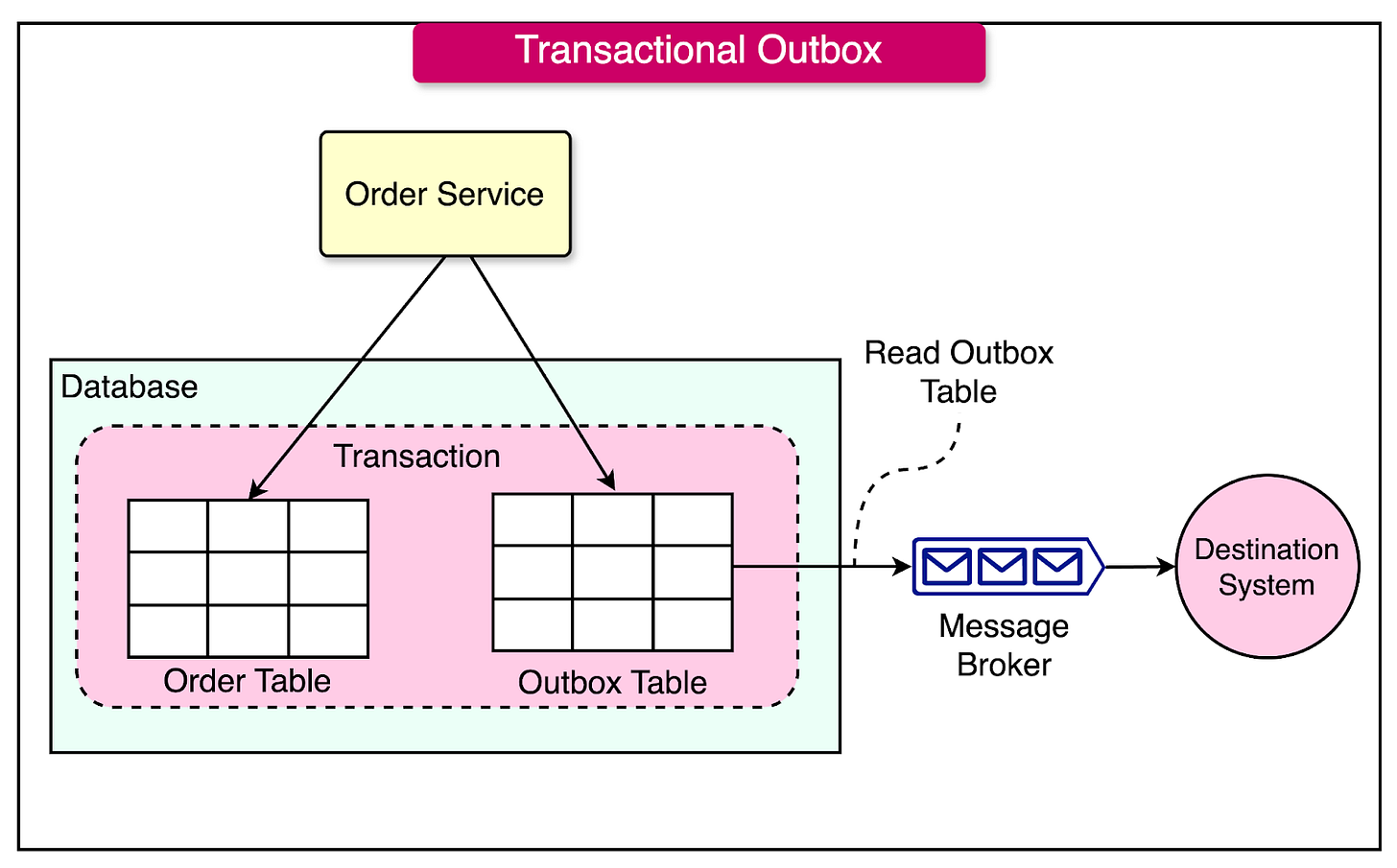

Atomicity of Database Updates and Event Publishing: Each step of a choreography-based Saga involves updating the database and publishing an event. These operations must happen atomically to maintain data consistency. To achieve this, services can use the transactional outbox pattern, ensuring that either both the database update and the event publication succeed or neither does.

Correlation IDs for Event Mapping: Services need to map each received event to their data. To facilitate this, events should contain a correlation ID that enables other participants to perform the necessary mapping. For instance, in the Create Order Saga, participants can use the order ID as a correlation ID passed from one participant to the next. This ensures that each service can correctly identify and process the relevant events.

See the diagram below for understanding more about the transactional outbox pattern:

Benefits of Choreography-based Sagas

Choreography-based Sagas offer several benefits:

Simplicity: Services publish events when they create, update, or delete business objects, simplifying the implementation of the Saga.

Loose Coupling: Participants subscribe to events without having direct knowledge of each other, promoting loose coupling and reducing dependencies between services.

Drawbacks of Choreography-based Sagas

While Choreography-based Sagas have several advantages, they also present some challenges:

Complexity in Understanding: Unlike orchestration, where the Saga workflow is defined in a single place, choreography distributes the implementation among the services. This can make it more difficult for developers to understand how a given Saga works.

Cyclic Dependencies: The services subscribe to each other’s events, often creating cyclic dependencies. For example, in the order processing scenario, there may be cyclic dependencies between the Order Service, Payment Service, and other participants.

Risk of Tight Coupling: Each Saga participant needs to subscribe to all events that affect them. This can lead to tight coupling, as services must be updated in lockstep with the lifecycle of other services.

Summary

As we have understood in this article, the Saga pattern is one of the most effective ways to implement a business transaction in a microservices architecture.

Let’s summarize what we have learned in this article:

Business transactions can be significantly more complex than traditional database transactions. In contrast, implementing this business transaction in a microservice architecture is much more complicated. In microservices, the needed data is scattered across multiple services.

The traditional approach to maintaining data consistency across multiple services, databases, or message brokers involves using distributed transactions.

In modern application development, alternative approaches such as the Saga pattern are often preferred for managing complex business transactions.

A saga is a sequence of local transactions, each updating data within a single service using familiar ACID transaction frameworks and libraries.

There are two major ways of implementing a Saga - Orchestration-based and Choreography-based.

In an Orchestration-based Saga, the orchestrator communicates with the participants by sending command messages that specify the operations to be performed.

In a Choreography-based Saga, each service involved in the Saga communicates directly with others by publishing events.