Event-driven architecture (EDA) is a software design approach emphasizing the production, detection, consumption, and reaction to events. In this architecture, events are state changes or updates within a system.

EDA is particularly beneficial in modern software development because it can decouple services, enhance scalability, and improve responsiveness.

By allowing systems to react to events asynchronously, EDA supports real-time processing and enables systems to handle high volumes of data efficiently. This approach is useful in distributed systems and microservices architectures, where different components must operate independently yet cohesively.

The importance of EDA in today's software landscape cannot be overstated. It offers significant advantages such as:

Improved fault tolerance because systems can continue operating even if some components fail.

Better resource utilization by enabling services to scale independently based on demand.

Supports dynamic and flexible workflows, allowing businesses to adapt quickly to changing requirements and market conditions.

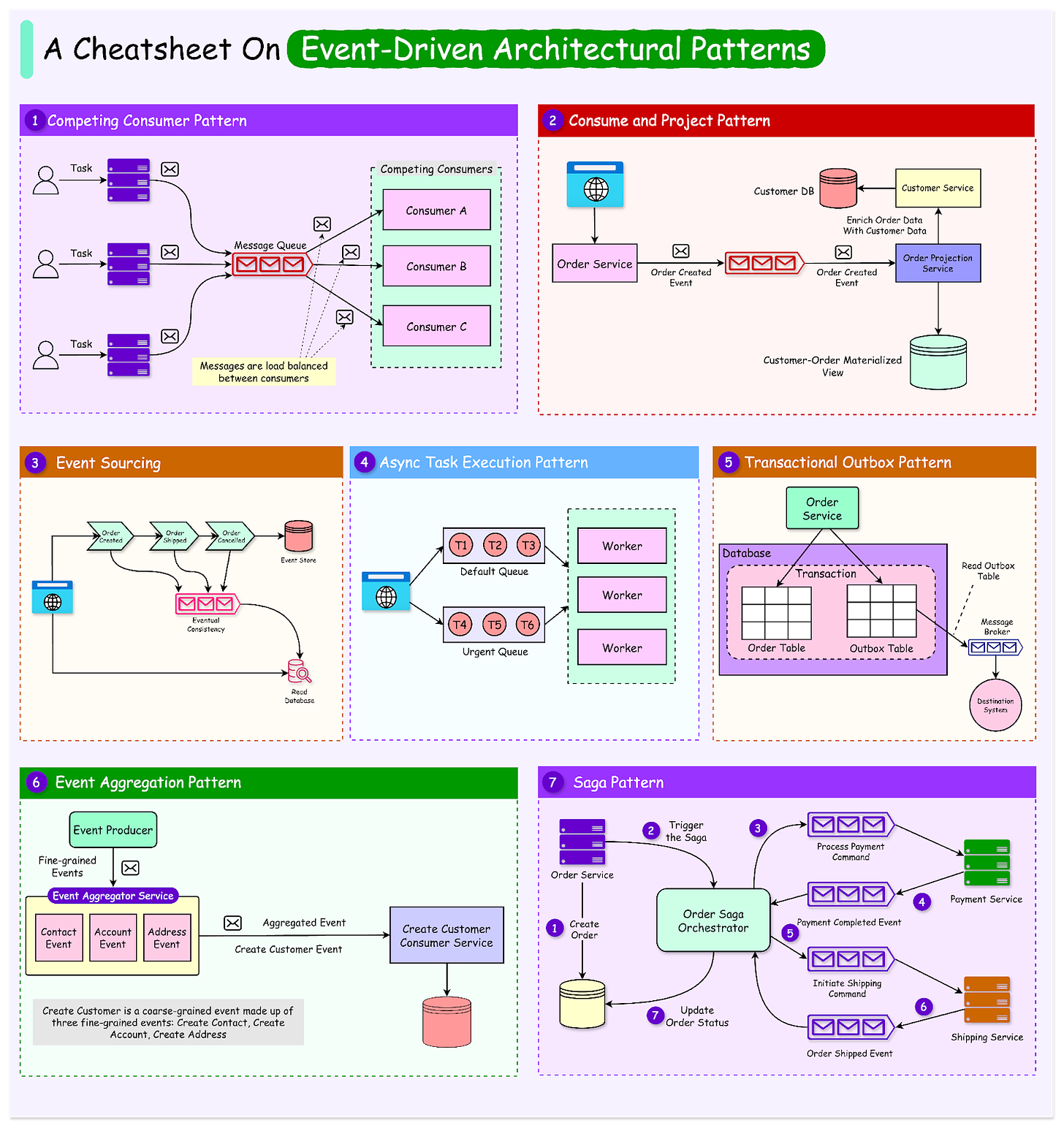

In this article, we’ll explore various patterns used in event-driven architecture. By examining these patterns, the aim is to gather insights into how they can be applied to build robust, scalable, and responsive systems.

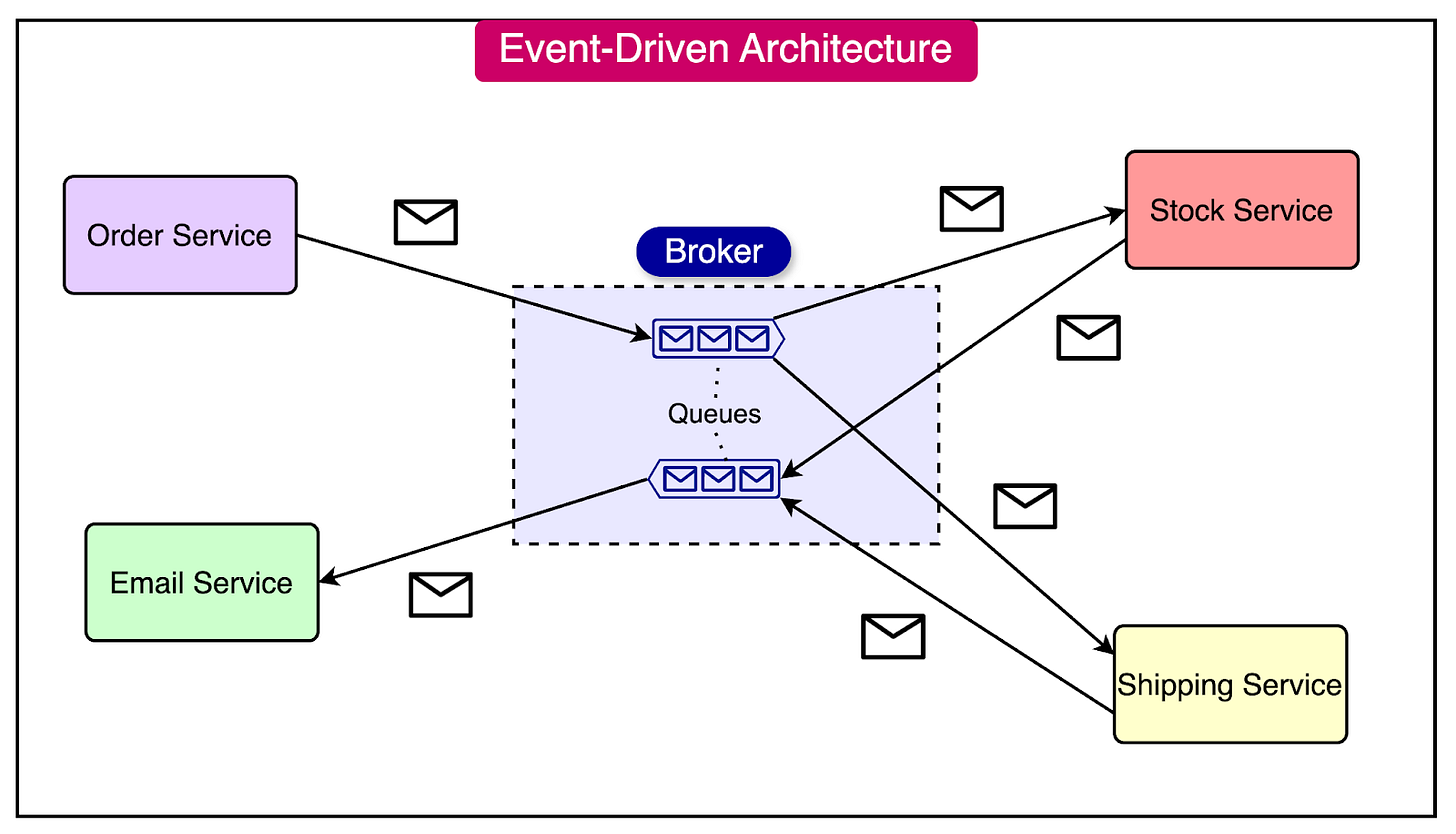

Core Components of EDA

To understand how EDA patterns work, it's essential to grasp the following key concepts:

Event Producers: They are responsible for generating events based on specific actions or changes in state within the system. Producers create and emit events that are then sent to an event broker.

Event Consumers: Consumers are components that subscribe to specific types of events and react to them by performing actions or triggering further processes. They receive events from the event broker and process them according to their defined logic.

Event Broker: The event broker acts as a mediator between event producers and event consumers. It receives events from producers, routes them to the appropriate consumers based on their subscriptions, and ensures reliable event delivery.

Event Streams: In EDA, events are often organized into event streams, which are continuous sequences of events generated by event producers. Event streams enable real-time data processing and facilitate communication between different components of a system.

See the diagram below that shows the components of event-driven architecture.

Event-driven architecture differs from traditional request-response architectures in several key aspects:

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous: In a request-response model, interactions between components are synchronous, meaning that a client sends a request and waits for a response before proceeding. In contrast, EDA operates asynchronously, allowing components to emit events and continue their execution without waiting for immediate responses.

Tight vs. Loose Coupling: Request-response architectures often lead to tight coupling between components, as clients directly communicate with servers. EDA promotes loose coupling by introducing an event broker as an intermediary, enabling components to communicate indirectly through events.

Scalability and Performance: As systems grow in complexity, request-response architectures can face scalability challenges due to the synchronous nature of interactions. EDA, on the other hand, allows for better scalability and performance by enabling asynchronous processing and independent scaling of components.

Event-Driven Architectural Patterns

Let’s now look at some of the most important patterns in event-driven architecture

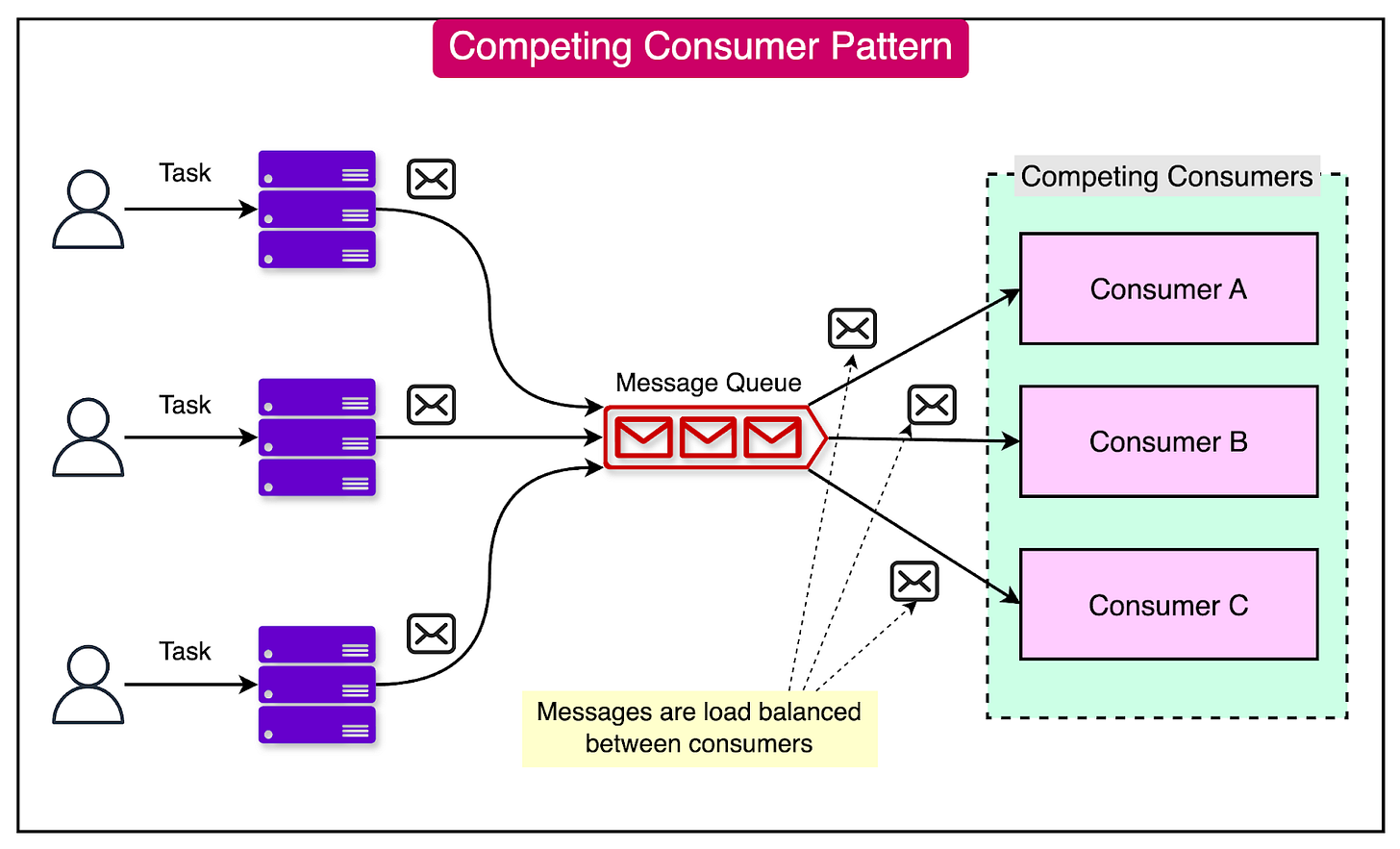

Competing Consumer Pattern

The competing consumer pattern is an EDA pattern that enables multiple consumers to compete for processing messages from a shared queue.

This pattern is useful in high-volume systems that require parallel processing to achieve scalability and improve throughput.

See the diagram below to understand the competing consumer pattern:

To understand how the competing consumer pattern works, let's explore its key concepts:

Shared Message Queue: In this pattern, an event broker, such as RabbitMQ, manages a shared queue of messages. This queue serves as a central repository where messages are stored and made available for consumption.

Competing Consumers: Multiple consumers subscribe to the shared message queue and compete with each other to retrieve and process messages as they become available. Each consumer independently pulls messages from the queue and processes them according to its logic.

Dynamic Load Balancing: The competing consumer pattern allows for dynamic load balancing by distributing the workload across multiple consumers. As the number of messages in the queue increases, additional consumers can be added to handle the increased load. Conversely, consumers can be removed when the load decreases.

Fault Tolerance: If one consumer fails or becomes unavailable, other consumers can continue processing messages from the queue. This redundancy ensures that the system remains operational even in the face of individual component failures, enhancing the overall fault tolerance and reliability of the system.

Some considerations to keep in mind when implementing competing consumer patterns are as follows:

Message Ordering: If message ordering is critical, additional mechanisms may be needed to ensure that messages are processed in the correct order. This can be achieved through techniques such as message partitioning or sequence numbers.

Message Idempotency: To handle potential message duplicates caused by consumer failures or retries, it's important to design consumers to be idempotent. Idempotent consumers can process the same message multiple times without causing unintended side effects.

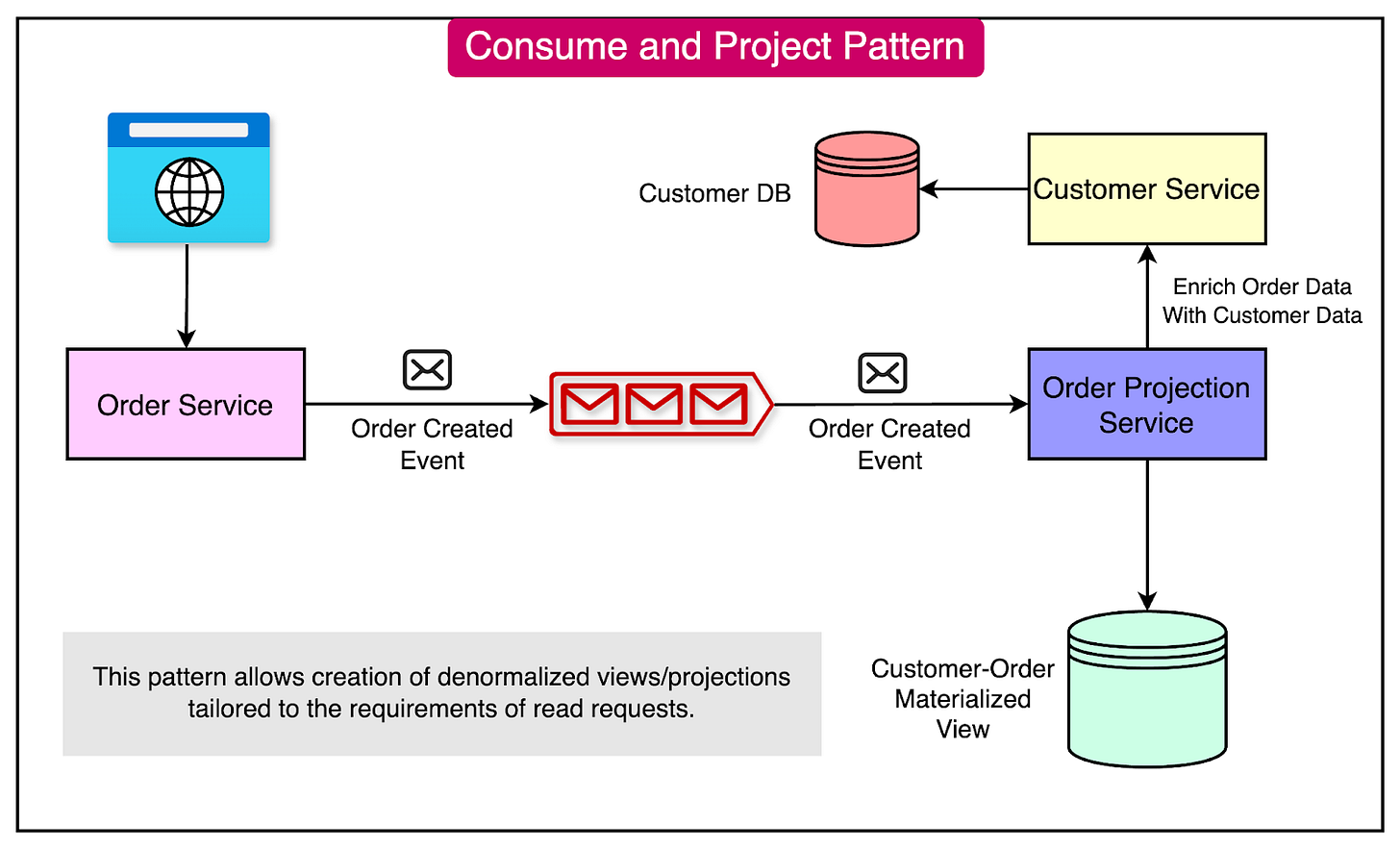

Consume and Project Pattern

The Consume and Project pattern is a strategy used in event-driven architectures to create materialized views from event streams, optimizing data access and reducing the load on legacy systems.

This pattern is particularly valuable when dealing with services that handle large volumes of requests for specific data, which can become bottlenecks due to their monolithic structure.

In a legacy system storing comprehensive metadata about various entities, a Consume and Project approach might involve:

Extracting only the necessary subset of metadata for a specific use case.

Storing the subset in a separate database optimized for those particular queries.

See the diagram below that shows this pattern where customer and order data is projected into a materialized view for read requests. The Order Projection Service receives the Order data via events and then enriches it by fetching customer data from Customer service.

Some of the key concepts of this pattern are as follows:

Event Streaming: The pattern begins with streaming relevant data changes from a primary database to an event broker. This includes updates or new entries significant to downstream services.

Write-Only Service: A dedicated service, often called a "write-only" service, consumes these events and projects a specific view of the data into its database.

Tailored Views: The projected view is tailored to meet the query needs of particular client services, effectively offloading specific queries from the original system.

The process flow works as follows:

Data changes are streamed from the primary database to an event broker.

A write-only service consumes these events.

The service projects a specific view of the data into a separate database.

Client services query this optimized view instead of the original system.

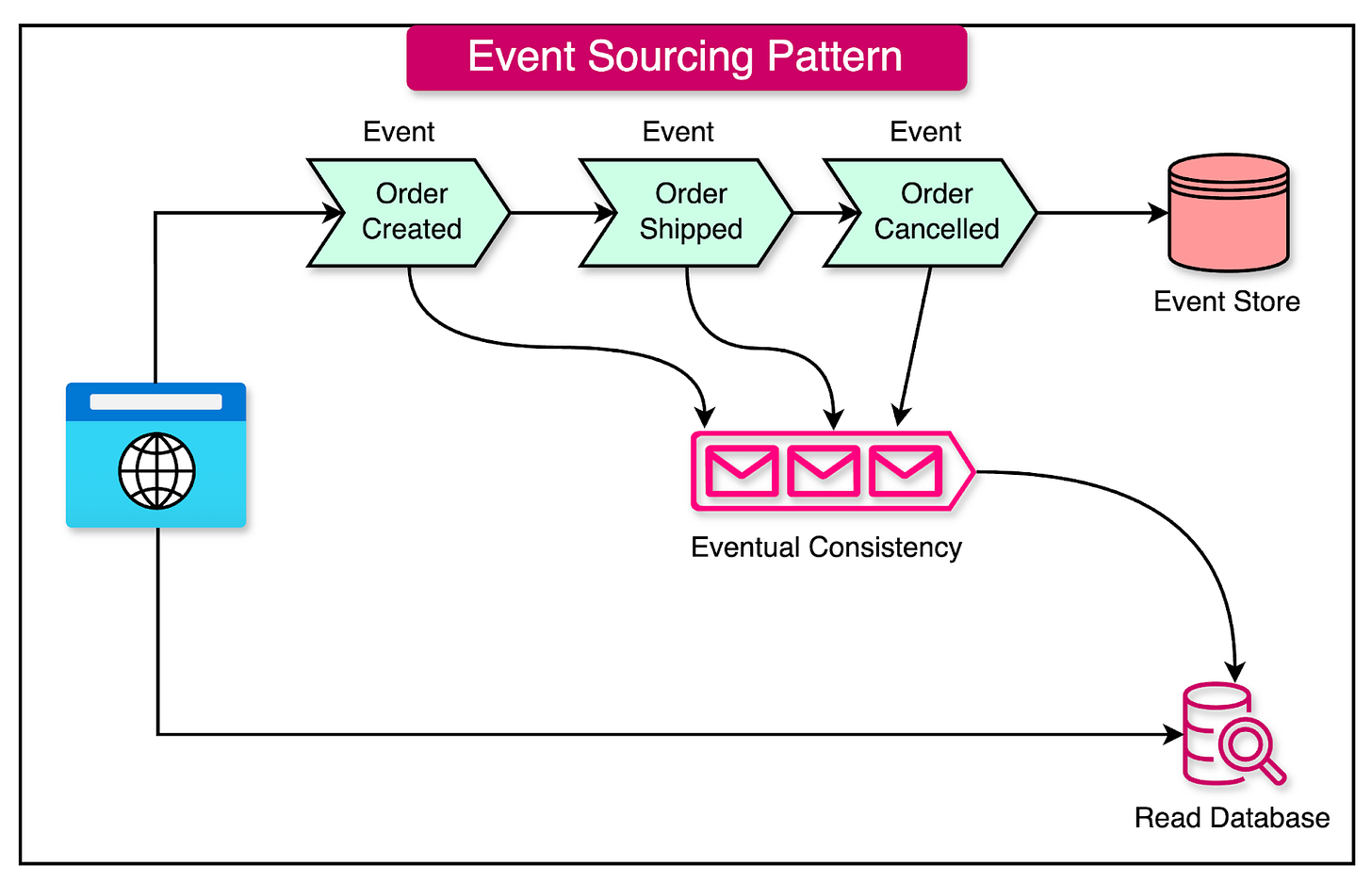

Event Sourcing

Event sourcing is an architectural pattern that fundamentally changes how data is stored and managed in software systems.

Instead of storing only the current state of an application, event sourcing focuses on capturing all changes to the application state as a sequence of events.

To understand how event sourcing works, it's essential to grasp the following key concepts:

Event Store: The event store is a durable log of all actions taken within the system. It functions as a database and a message broker, storing events and providing APIs for adding new events and retrieving existing ones.

Events: Each event represents a discrete change to the state and includes enough information to reconstruct that change. For example, in an order management system, events might include "Order Created," "Order Shipped," or "Order Cancelled."

State Reconstruction: By replaying the sequence of events, the current state of any entity can be reconstructed at any point in time. This enables temporal queries and provides a complete history of state changes.

Read Database: A separate eventually consistent read database can be maintained that provides the current state of the data for query purposes.

See the diagram below to get a better idea about event sourcing.

Event sourcing offers several key benefits:

Reliable Audit Trail: By capturing all state changes as events, event sourcing provides an immutable record of all actions taken within the system. This is particularly valuable in systems that require detailed audit logs for compliance reasons.

Temporal Queries: Event sourcing enables complex temporal queries, allowing developers to understand how the state of an entity evolved over time. This is crucial in applications where understanding the sequence of changes is important.

Concurrency and Conflict Resolution: Since events are stored sequentially, they provide a natural mechanism for handling concurrency and resolving conflicts in distributed systems.

However, while event sourcing offers numerous benefits, it also presents some challenges.

Event sourcing introduces a different way of thinking about data management, requiring developers to consider the data as events rather than direct state changes.

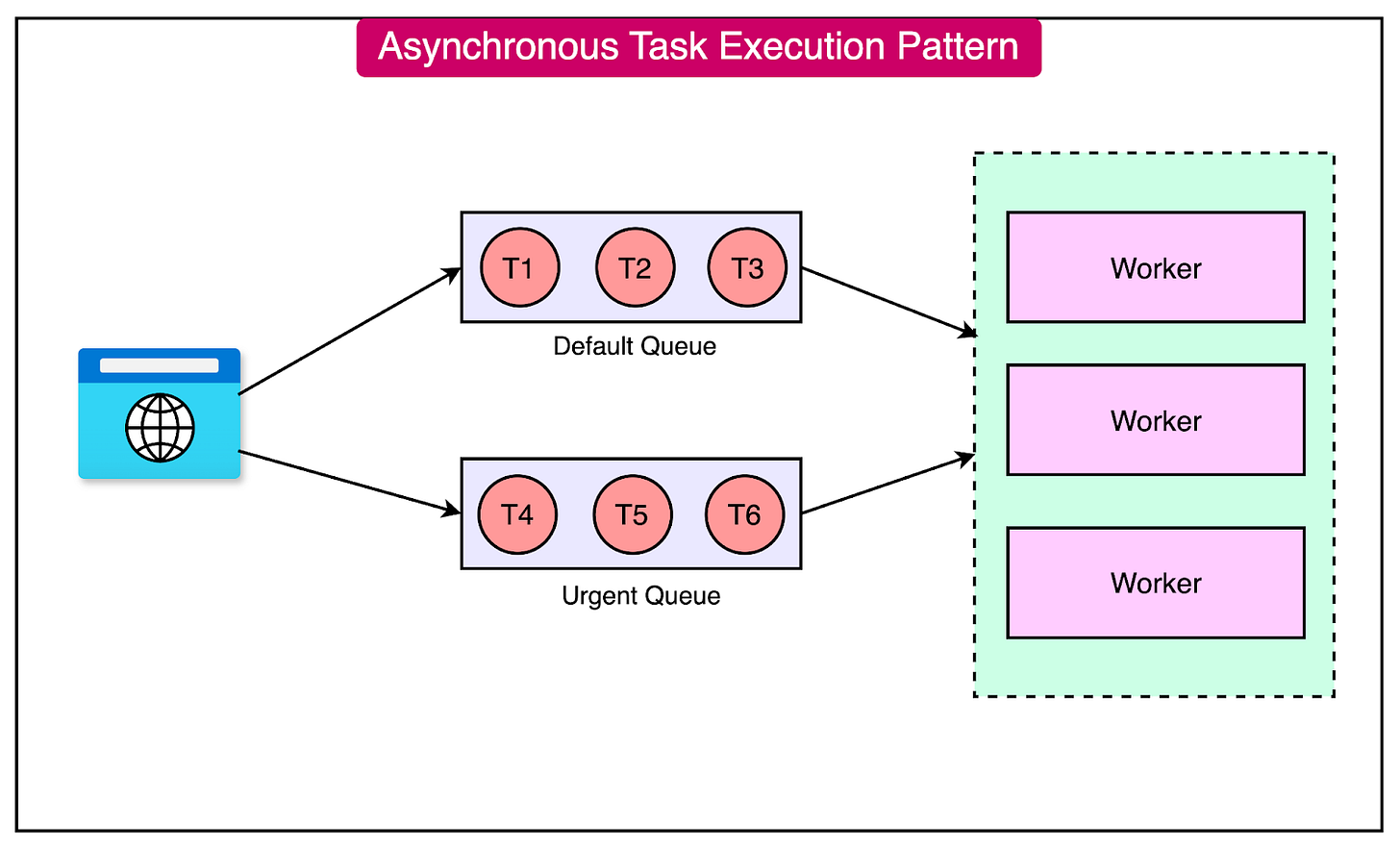

Asynchronous Task Execution Pattern

The Async Task Execution Pattern is an event-driven approach designed to ensure the eventual processing of scheduled tasks, even in the face of temporary failures.

The key components of this pattern are as follows:

Job Scheduler: Initiates tasks by producing messages to an event broker, representing the scheduled tasks that need to be processed.

Event Broker: A message queue, such as Apache Kafka, that stores and manages the task messages.

Workers: Instances that pick up messages from the event broker and attempt to execute the corresponding tasks.

Retry Policy: A predefined set of rules that govern how the consumer service should handle task failures and attempt retries.

See the diagram below:

The process flow in this pattern is as follows:

The job scheduler produces a message to the event broker, representing a scheduled task.

The worker service picks up the message from the event broker.

The worker attempts to execute the task.

If the task fails due to temporary issues, the worker retries processing the message based on the retry policy.

The retry policy often involves exponential backoff intervals to handle transient errors gracefully.

Some important considerations that should be kept in mind for implementing this pattern are as follows:

Retry Policy Design: Careful consideration must be given to the design of the retry policy to ensure it effectively handles various failure scenarios without causing unintended consequences.

Idempotency: Tasks should be designed to be idempotent, meaning that multiple executions of the same task should produce the same result to avoid inconsistencies during retries.

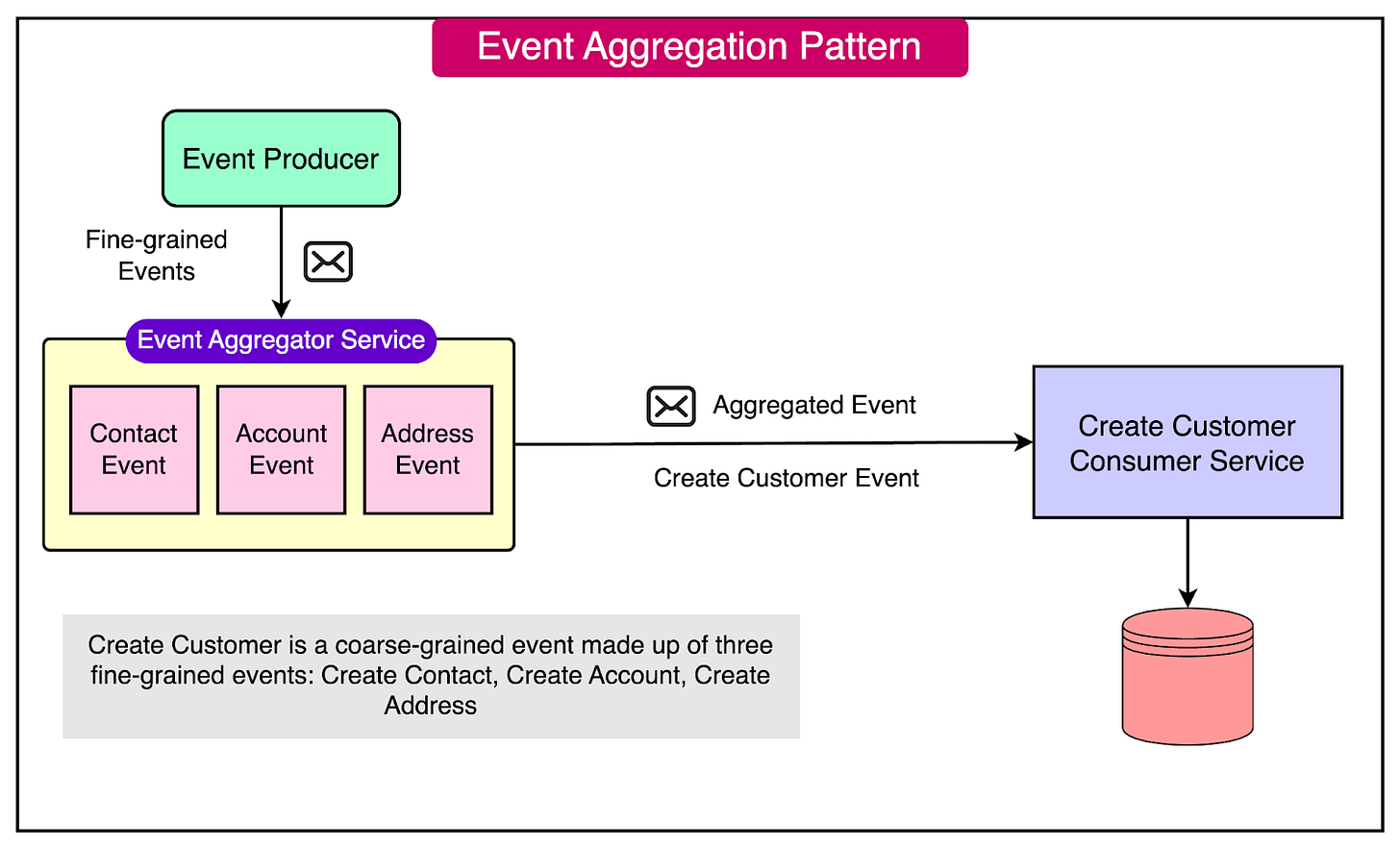

Event Aggregation Pattern

Event aggregation is a specific EDA pattern that focuses on combining multiple related events into a single, more comprehensive event.

It focuses on decoupling components and enabling asynchronous communication through events. The aim is to consolidate multiple fine-grained events into a single coarse-grained event. The event aggregator collects and processes multiple events before producing a new, aggregated event.

For example, consider the below fine-grained events:

Create Contact: A new customer contact is created in the system, triggering a fine-grained event.

Create Account: An account is created for the customer, triggering another fine-grained event.

Create Address: The customer’s shipping address is added, triggering a third fine-grained event.

See the diagram below:

The event aggregator service consolidates the fine-grained Contact, Account, and Address events into a single coarse-grained “Create Customer” event. The event aggregator maintains the relationships between the entities (Contact, Account, Address) and the overall “Customer”.

When all the fine-grained events have been received, the aggregator raises the consolidated “Create Customer” event to downstream consumers.

The main advantage of this aggregation is reduced chattiness and network overhead from multiple fine-grained events. Also, it results in simplified event handling for consumers.

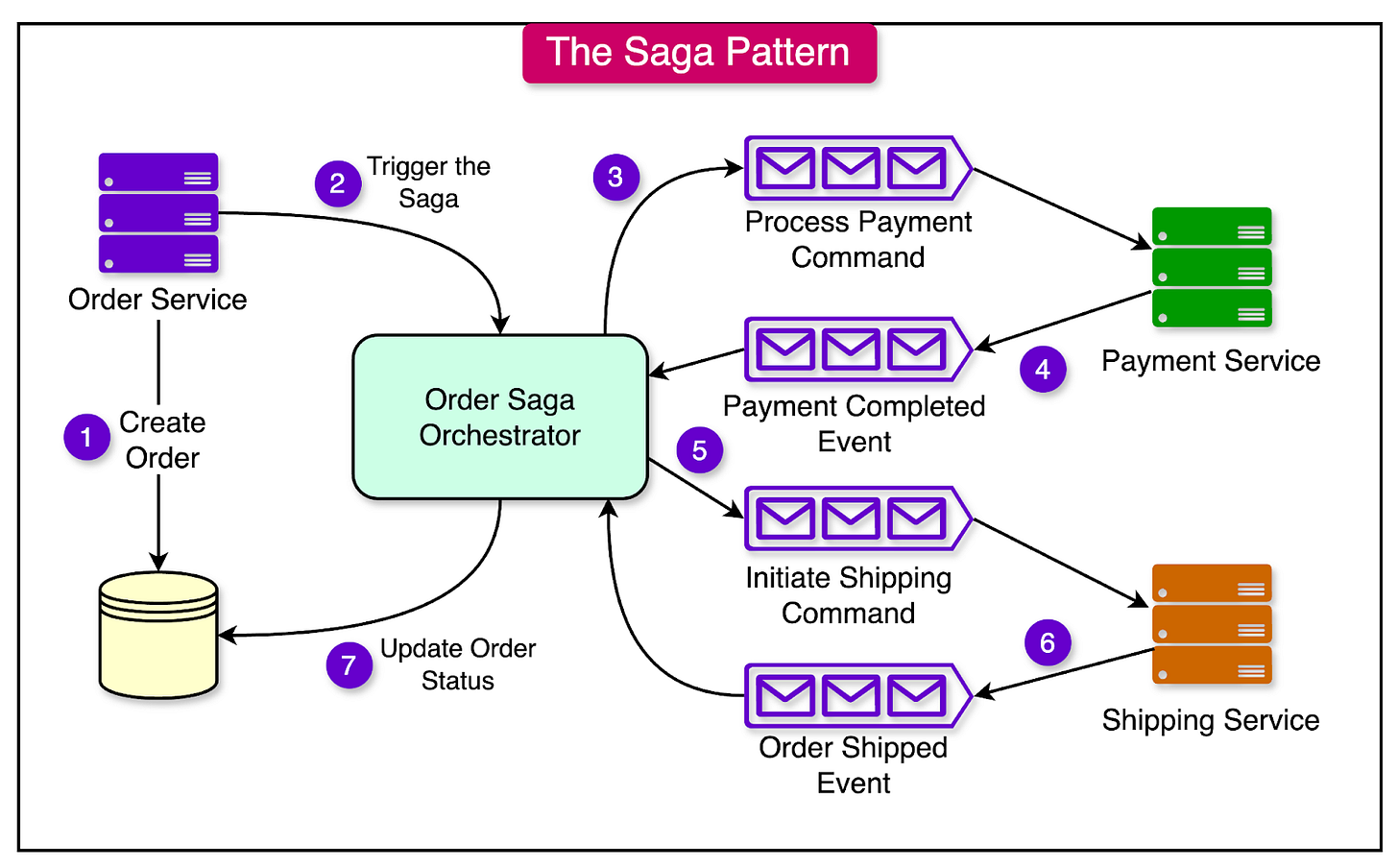

The Saga pattern is a design strategy used to manage distributed transactions across multiple services without relying on the traditional two-phase commit (2PC) protocol.

In distributed systems, particularly those employing microservices, maintaining data consistency across services can be challenging due to the lack of a centralized transaction manager. The Saga pattern addresses the challenges of distributed transactions by breaking them down into a series of smaller, independent steps, each managed by its service.

The key concepts of the Saga pattern include:

Local Transactions: Each step in the saga is a local transaction that updates the state within a single service.

Event-Driven Communication: After completing a local transaction, each service publishes an event to trigger the next step in the saga.

Compensating Actions: If any step in the saga fails, compensating actions are executed to undo the changes made by previous steps, ensuring that the system eventually reaches a consistent state.

A typical use case for the Saga pattern is in long-running business processes, such as order fulfillment in an e-commerce platform. The process involves multiple services, each responsible for a specific task:

Order Service: Manages the order placed by the customer.

Payment Service: Processes the payment for the order.

Shipping Service: Updates the shig information for the order.

Each of these operations is a step in the saga. If the shipping initiation fails after the payment has been placed, a compensating transaction would reverse the payment.

EDA plays a crucial role in implementing the Saga pattern by facilitating communication between services through events. Here are some key points to keep in mind:

Event Publishing: When a service completes its local transaction, it publishes an event to notify the next service in the saga.

Event Consumption: The next service in the saga consumes the event and performs its local transaction based on the received information.

Decoupling of Services: EDA allows services to operate independently and be scaled based on demand, enhancing fault tolerance and scalability.

Eventual Consistency: By allowing each service to update its state and react to events asynchronously, EDA supports eventual consistency in distributed systems.

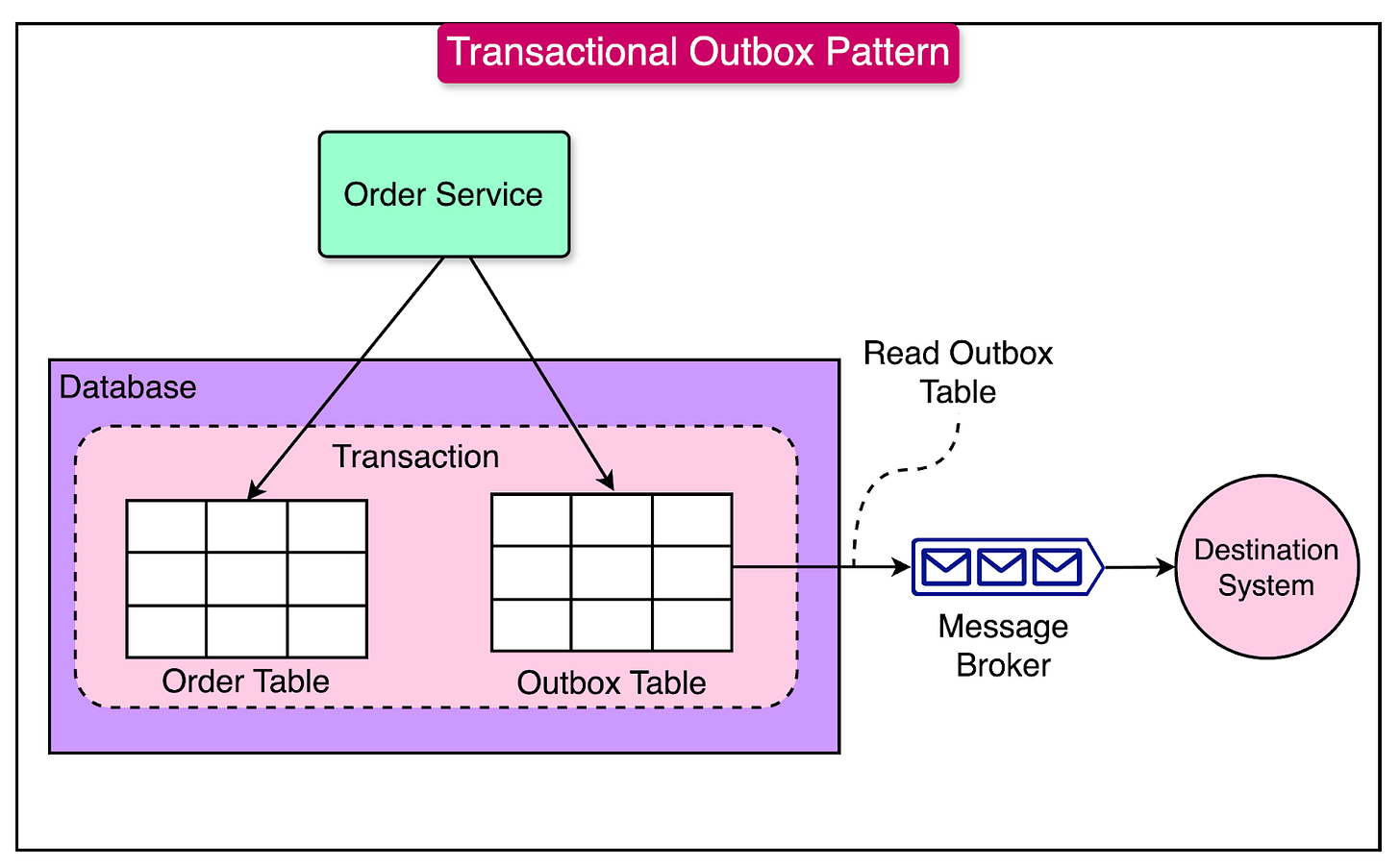

Transactional Outbox Pattern

The Transactional Outbox pattern is a fundamental EDA pattern that ensures the atomicity of state changes and event publication without relying on distributed transactions like two-phase commit (2PC).

This pattern addresses the challenge of maintaining consistency between a service's internal state and the events it publishes, particularly in microservices-based systems.

The key concepts of the Transactional Outbox pattern are as follows:

Local Transactions: The pattern uses a local database transaction to update the business data and an outbox table within the same database.

Outbox Table: Serves as a temporary holding area for events that need to be published.

Event Publication: A separate process or thread periodically scans the outbox table for new events, publishes them to an event broker, and marks them as sent.

This pattern decouples event production from consumption, allowing for reliable event delivery without risking inconsistencies due to partial failures.

See the diagram below:

Here’s a process flow for the pattern:

When a service processes a transaction, it performs two operations within a single database transaction:

Updates the relevant business entities.

Inserts a corresponding event into the outbox table.

After the transaction is committed, a separate process or thread scans the outbox table for new events.

It publishes the events to an event broker and marks the events as sent in the outbox table.

The transactional outbox pattern is particularly beneficial in scenarios where idempotency and consistency are critical, such as an e-commerce platform handling order processing:

When an order is placed, the order service updates the order database and inserts an event into the outbox table within a single transaction.

A separate process publishes the event to a message broker, triggering downstream services like inventory management and shipping.

If the event publication fails due to network issues, it remains in the outbox until successfully processed, ensuring the order is not lost or duplicated.

Summary

In this article, we’ve taken a detailed look at the most popular EDA patterns. Each pattern has benefits and trade-offs and can be used depending on the project requirements.

Let’s summarize the key learnings from this article:

EDA is particularly beneficial in modern software development because it can decouple services, enhance scalability, and improve responsiveness.

Core components of EDA include Event Producers, Event Consumers, Event Brokers, and Event Streams.

Multiple EDA patterns are available for use in different scenarios.

The Competing Consumer pattern is a design approach within event-driven architectures that enables multiple consumers to compete for processing messages from a shared queue.

The Consume and Project pattern is used in event-driven architectures to create materialized views from event streams.

Event Sourcing is an architectural pattern that fundamentally changes how data is stored and managed in software systems.

The Async Task Execution pattern is an event-driven approach designed to ensure the eventual processing of scheduled tasks, even in the face of temporary failures.

The Events Aggregation pattern is a method within event-driven architectures designed to confirm the completion of a batch process by aggregating events.

The Saga pattern is a design strategy used to manage distributed transactions across multiple services without relying on the traditional two-phase commit (2PC) protocol.

The Transactional Outbox pattern ensures the atomicity of state changes and event publication without relying on distributed transactions.