Authentication serves as the first line of defense in ensuring the security of applications and the sensitive data they handle.

Whether it’s a personal banking app, a corporate platform, or an e-commerce website, effective authentication mechanisms are needed to verify the identity of users and safeguard their access to resources.

Authentication ensures that only authorized users gain access to specific data or actions within an application. Without proper authentication, applications are vulnerable to unauthorized access, data breaches, and malicious attacks, potentially resulting in significant financial loss, reputational damage, and privacy violations.

In addition to security, authentication plays a critical role in the user experience. By effectively identifying users, applications can provide personalized services, remember user preferences, and enable functionalities like Single Sign-On (SSO) across platforms.

With evolving threats, implementing secure and efficient authentication is more challenging than ever. Developers must navigate between competing priorities such as:

Security: Ensuring protection against different attack types like session hijacking, token theft, and replay attacks.

Scalability: Supporting millions of users without compromising performance.

User Experience: Maintaining ease of use while applying strong security measures.

To tackle these challenges, developers rely on various authentication mechanisms. In this post, we’ll explore multiple authentication mechanisms used in modern applications and also study their advantages and disadvantages.

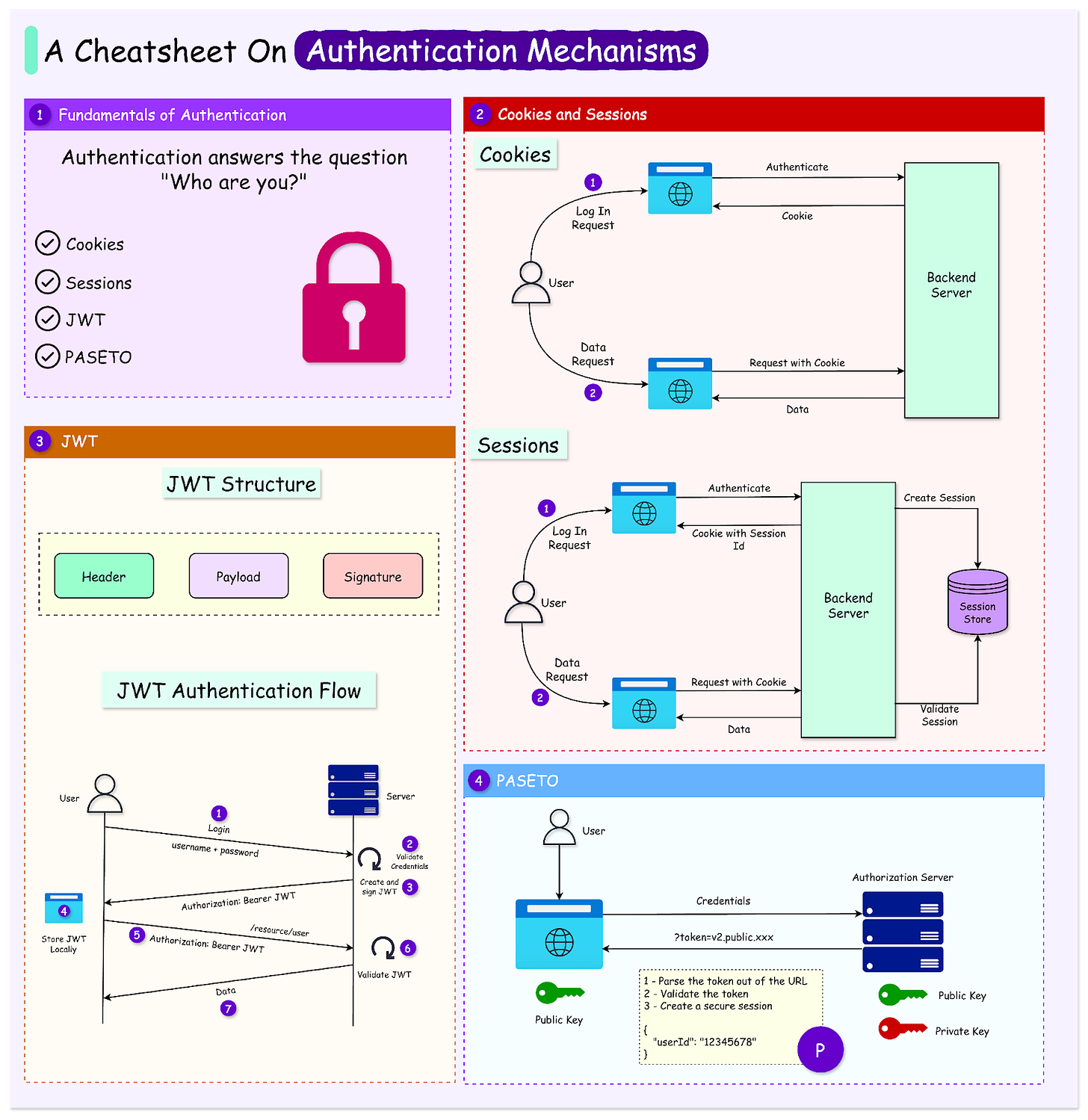

Fundamentals of Authentication

Authentication is the process of verifying the identity of a user, device, or system attempting to access an application.

In simpler terms, it is how an application ensures that a person or system is who they claim to be. It often involves validating credentials such as usernames, passwords, biometric data, or tokens.

For example:

When you log in to a website using a password, the application compares your input with stored credentials to confirm your identity.

In API-based systems, applications might use tokens to verify that the calling service has the right to interact with the backend.

Authentication vs Authorization

Authentication and authorization are closely related but distinct processes:

Authentication: Answers the question, "Who are you?" and focuses on verifying identity.

Authorization: Answers the question, "What are you allowed to do?" by determining the permissions or access levels granted to an authenticated user.

For example, authentication verifies that you are a registered user of an e-commerce platform. Authorization determines whether you can view the order history or manage the inventory as an admin.

In other words, while authentication establishes identity, authorization enforces access control based on that identity.

Authentication with Cookies and Sessions

We will now look at the use of cookies and sessions concerning authentication.

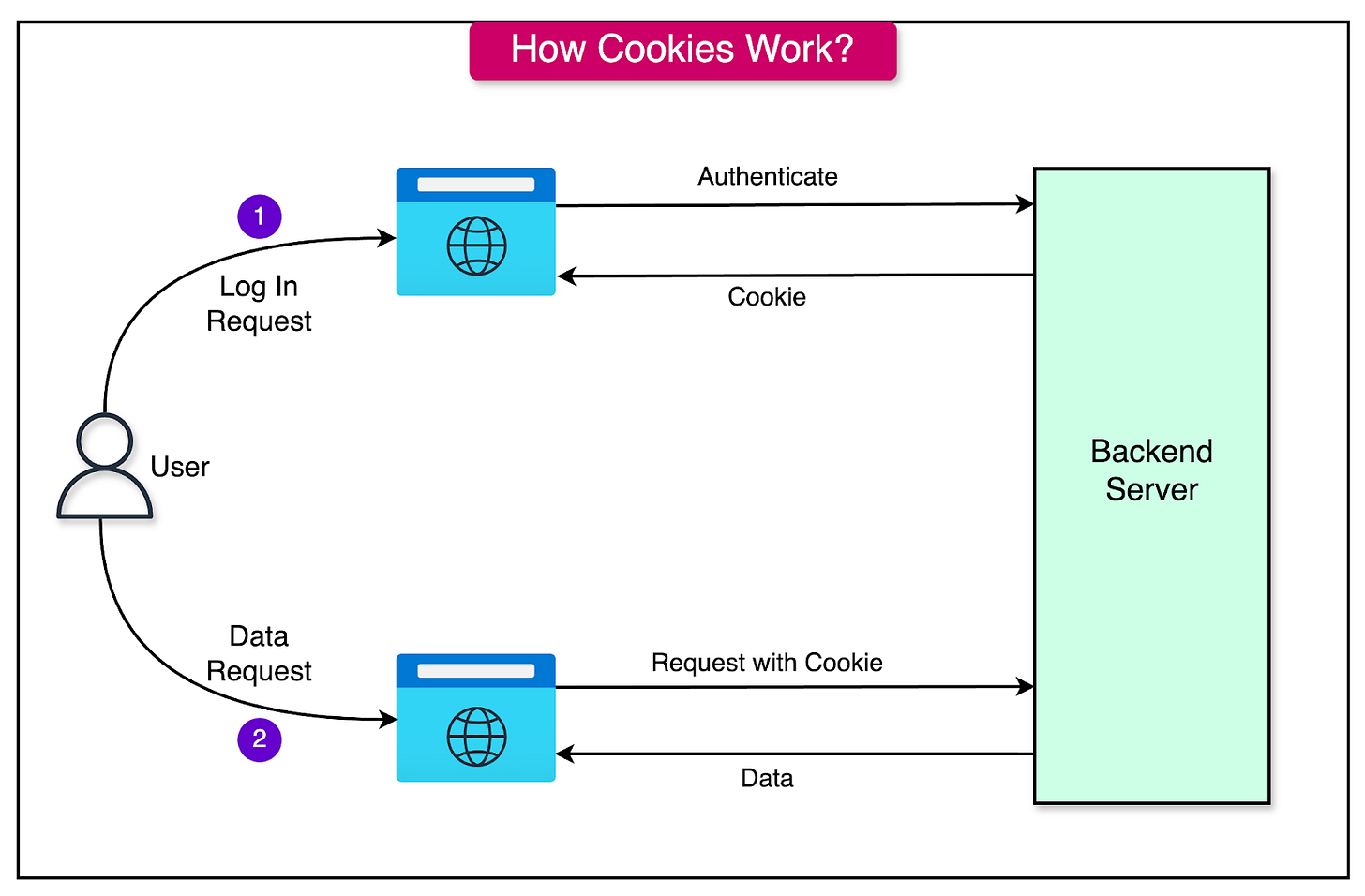

Cookies

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on the client’s browser by a web server. They play a key role in maintaining state in otherwise stateless HTTP communication by enabling web applications to remember information across multiple requests.

Cookies allow web servers to store data that persists between requests, making them useful for various purposes such as:

Session Management: Tracking logged-in users with session IDs.

Personalization: Storing user preferences or settings.

Analytics and Tracking: Recording user behavior for analytics or targeted advertising.

In authentication, cookies are commonly used to store session tokens or identifiers that validate a user’s identity.

The process typically involves two parts:

User Login:

The user provides credentials (e.g., username and password).

The server authenticates the credentials and generates a session ID or token.

This session ID is sent to the browser and stored in a cookie.

Subsequent Requests:

The browser automatically includes the cookie in the Cookie header of each HTTP request.

The server reads the session ID from the cookie, verifies it, and identifies the user.

Advantages of Using Cookies

The main advantages of using cookies are as follows:

Widely Supported: Supported natively by all major browsers.

Persistent Storage: Cookies can be set to expire after a specific time or persist until the user manually clears them.

Automatic Transmission: Browsers automatically send cookies with every request to the originating domain and therefore, developers don’t have to write additional code to handle cookie transmission.

Customizable: Attributes like HttpOnly, Secure, and SameSite enhance security and control behavior.

Challenges of Using Cookies

Cookies also have several challenges:

Vulnerability to Cross-Site Scripting (XSS): If a malicious script is injected into a website, it could access cookies containing sensitive data. To prevent JavaScript access, we can set the HttpOnly flag.

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks: If cookies are transmitted over unencrypted HTTP, they can be intercepted and stolen. Setting the Secure flag ensures that cookies are only sent over HTTPS.

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF): Cookies automatically sent with requests can be exploited to perform unauthorized actions. To mitigate this, we can implement a CSRF token and use the SameSite attribute.

Storage Limits: Browsers impose size limits (typically 4KB per cookie) and quantity limits per domain. Therefore, it is important to store only essential data in cookies.

Cookie Overflow: Too many cookies can lead to performance issues or request rejection. Therefore, it is important to use cookies judiciously.

Best Practices for Secure Cookie Handling

Some best practices worth keeping in mind while using cookies are as follows:

Set HttpOnly Flag: Prevents access to cookies via JavaScript, mitigating XSS risks.

Set Secure Flag: Ensures cookies are sent only over HTTPS.

Use SameSite Attribute: Restricts cross-site requests, reducing CSRF risks. For example, use SameSite=Strict or SameSite=Lax.

Limit Expiry: Use short expiration times for sensitive data.

Avoid Storing Sensitive Information: Store tokens or identifiers, not raw credentials or sensitive data.

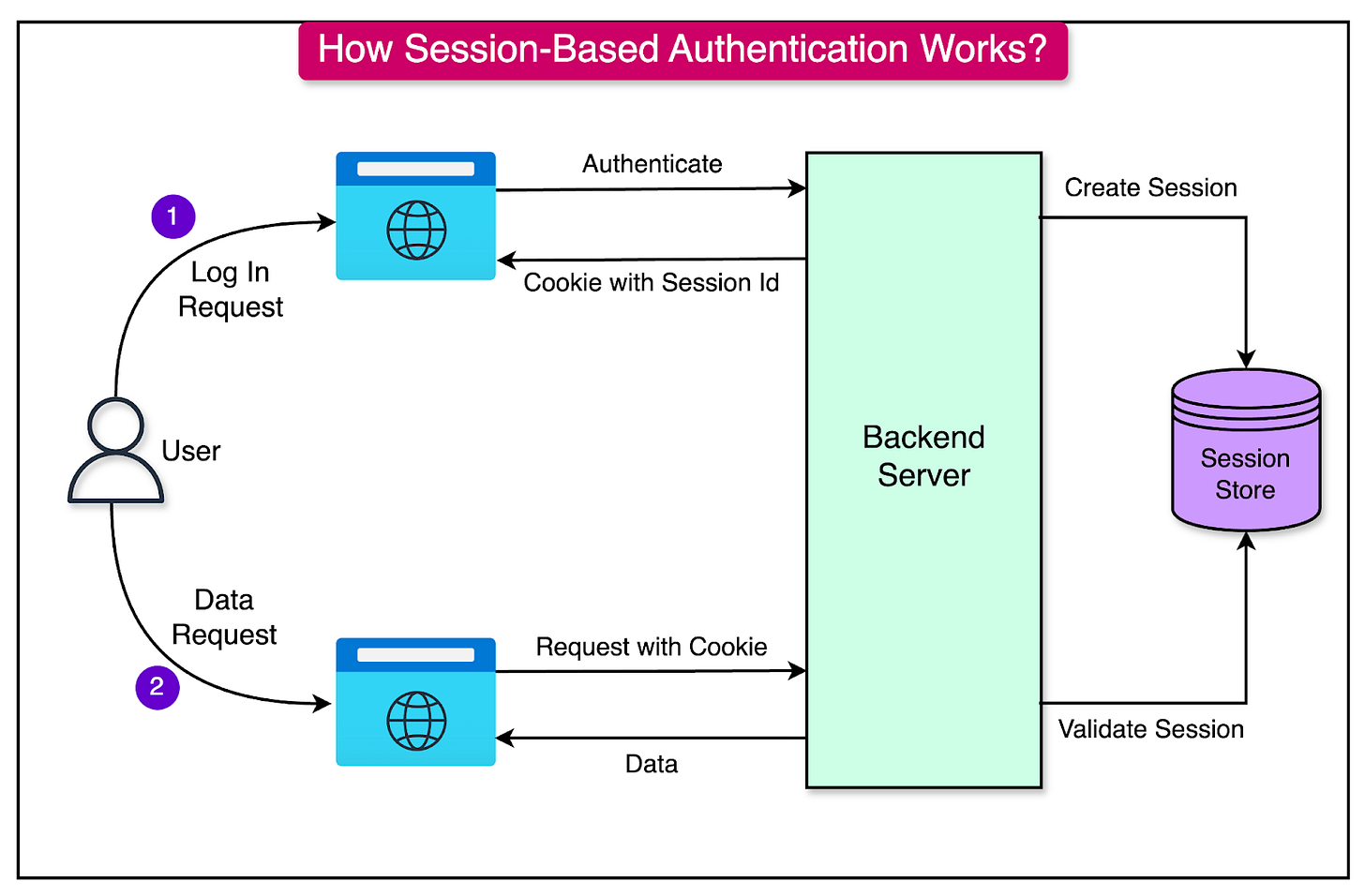

Sessions

Sessions are a server-side mechanism used to store and manage user authentication data during an active interaction with an application.

Unlike cookies, which store data on the client side, sessions keep the data securely on the server, with the client holding only a reference (usually a session ID).

How Sessions Work in Server-Side Authentication?

Here are the primary steps:

User Login:

The user submits credentials (e.g., username and password) to log in.

The server authenticates the credentials and creates a session for the user, typically represented by a unique session ID.

Session ID Generation:

The session ID is a random, unique identifier linked to the user’s session data stored on the server.

This session ID is sent to the client in a cookie or via another transport mechanism (e.g., in the response body).

Storing Session Data:

The server stores the session data (e.g., user ID, roles, preferences) in memory, a database, or another storage system.

The session ID acts as a key to retrieve this data.

Maintaining the Session:

For each subsequent request, the client sends the session ID (usually via a cookie).

The server validates the session ID, retrieves the associated data, and uses it to process the request.

Session Expiration:

Sessions can have a time-to-live (TTL) to automatically expire after a period of inactivity or after a maximum duration.

Session Invalidation:

When the user logs out or a session is revoked (e.g., due to security concerns), the session data is deleted from the server, and the session ID becomes invalid.

See the diagram below to understand session-based authentication with cookies.

Relationship Between Sessions and Cookies

Cookies and sessions often work together.

Cookies can be used to hold the session ID on the client side. For each request, the browser sends the cookie to the server, allowing the server to identify the user’s session.

See the code example below that shows how a session id is set to the cookie.

app.post('/login', (req, res) => {

const sessionId = createSession(req.body.username);

res.cookie('session_id', sessionId, {

httpOnly: true, // Prevent access via JavaScript

secure: true, // Ensure the cookie is sent over HTTPS

maxAge: 3600000 // Set expiration time (1 hour)

});

res.send('Login successful');

});For an incoming request, the session ID stored in the cookie can be read by the server as follows:

app.get('/profile', (req, res) => {

const sessionId = req.cookies['session_id'];

if (isValidSession(sessionId)) {

res.send('Profile page');

} else {

res.status(401).send('Unauthorized');

}

});Note that these code snippets are just simple examples to help understand the concept in a better manner. In a real production application, the session generation logic would be different.

Advantages of Using Sessions

There are several advantages of using sessions:

Secure Storage: Session data resides on the server, reducing the risk of exposure to client-side vulnerabilities like Cross-Site Scripting (XSS).

Flexibility: Sessions can store complex user data, such as roles, permissions, and preferences, without bloating client-side storage.

Revocability: Sessions can be invalidated on the server, allowing for immediate termination of user access.

Compatibility: Well-suited for traditional web applications where requests frequently return to the same server.

Challenges of Using Sessions

Sessions also pose some challenges:

Scalability: In distributed systems (e.g., microservices), session data must be shared across servers, requiring additional infrastructure like centralized databases or sticky sessions. These solutions add complexity and potential bottlenecks.

Session Hijacking: If an attacker steals a session ID, they can impersonate the user. This can be mitigated by using HTTPS to encrypt data in transit and implementing session timeout.

Storage Overhead: Large numbers of active sessions can consume significant server resources. This can be mitigated by using an efficient session storage.

Authentication with JWTs

JSON Web Tokens (JWT) are a compact, URL-safe, self-contained token format used to securely transmit information between parties.

JWTs are often employed for authentication and authorization to enable stateless and scalable systems. The token contains all the necessary data to validate the user's identity, removing the need for server-side session storage.

Structure of a JWT

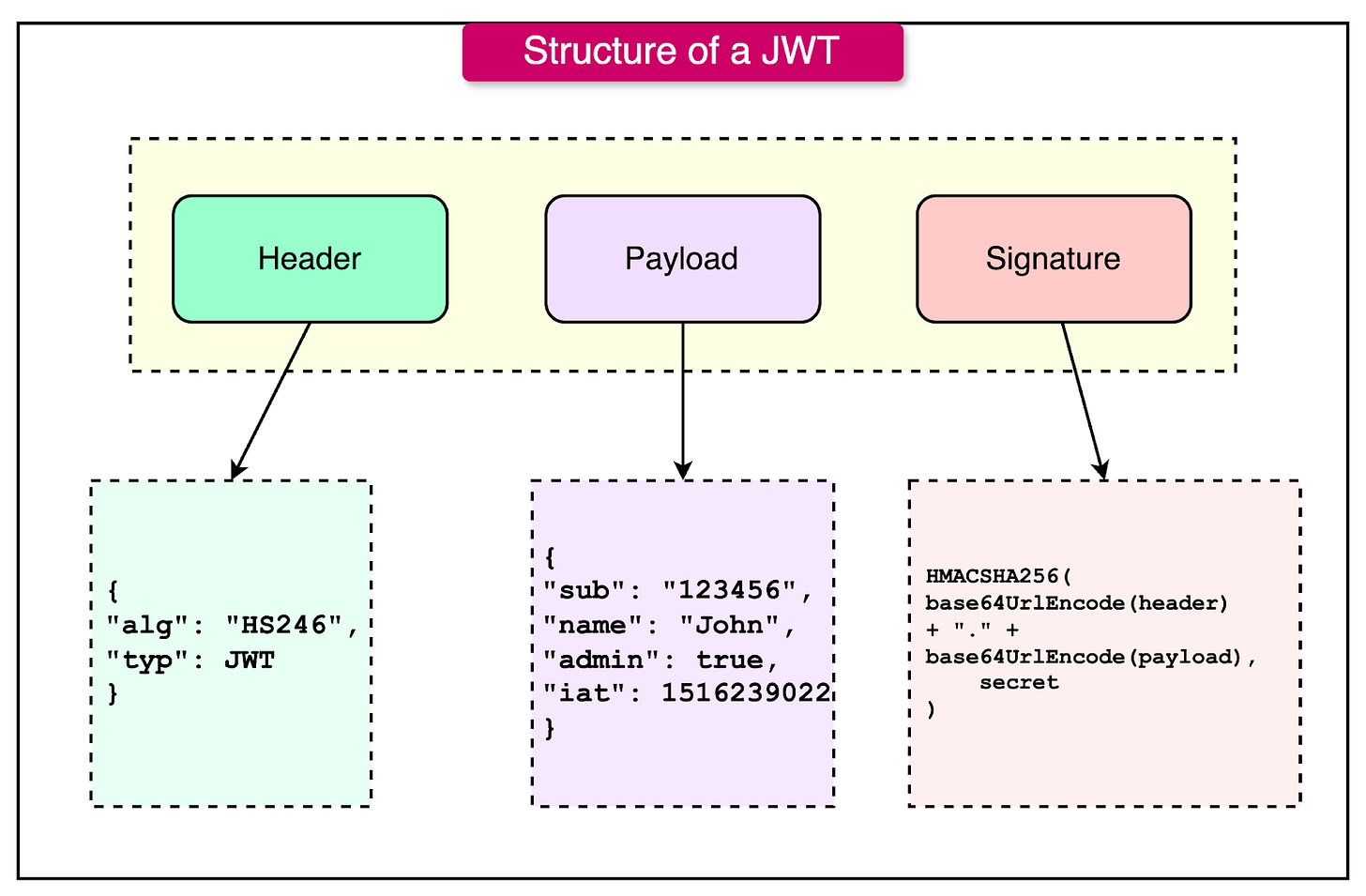

The diagram below shows the structure of a JWT.

As we can see, the JWT consists of three parts, encoded in Base64:

Header: Contains metadata about the token, including the type (JWT) and the signing algorithm (e.g., HS256, RS256).

{

"alg": "HS256",

"typ": "JWT"

}Payload: Contains the claims, which are statements about the user or token. Claims can be:

Registered Claims: Predefined claims like iss (issuer), exp (expiration time), sub (subject).

Public Claims: Custom claims defined by the application.

Private Claims: Custom claims shared between the issuer and consumer.

{

"sub": "1234567890",

"name": "John Doe",

"admin": true,

"iat": 1516239022

}Signature: Ensures the integrity of the token and verifies the authenticity of the sender. It is created by encoding the header and payload and signing them with a secret or private key.

HMACSHA256(

base64UrlEncode(header) + "." + base64UrlEncode(payload),

secret

)How JWT Works In Authentication

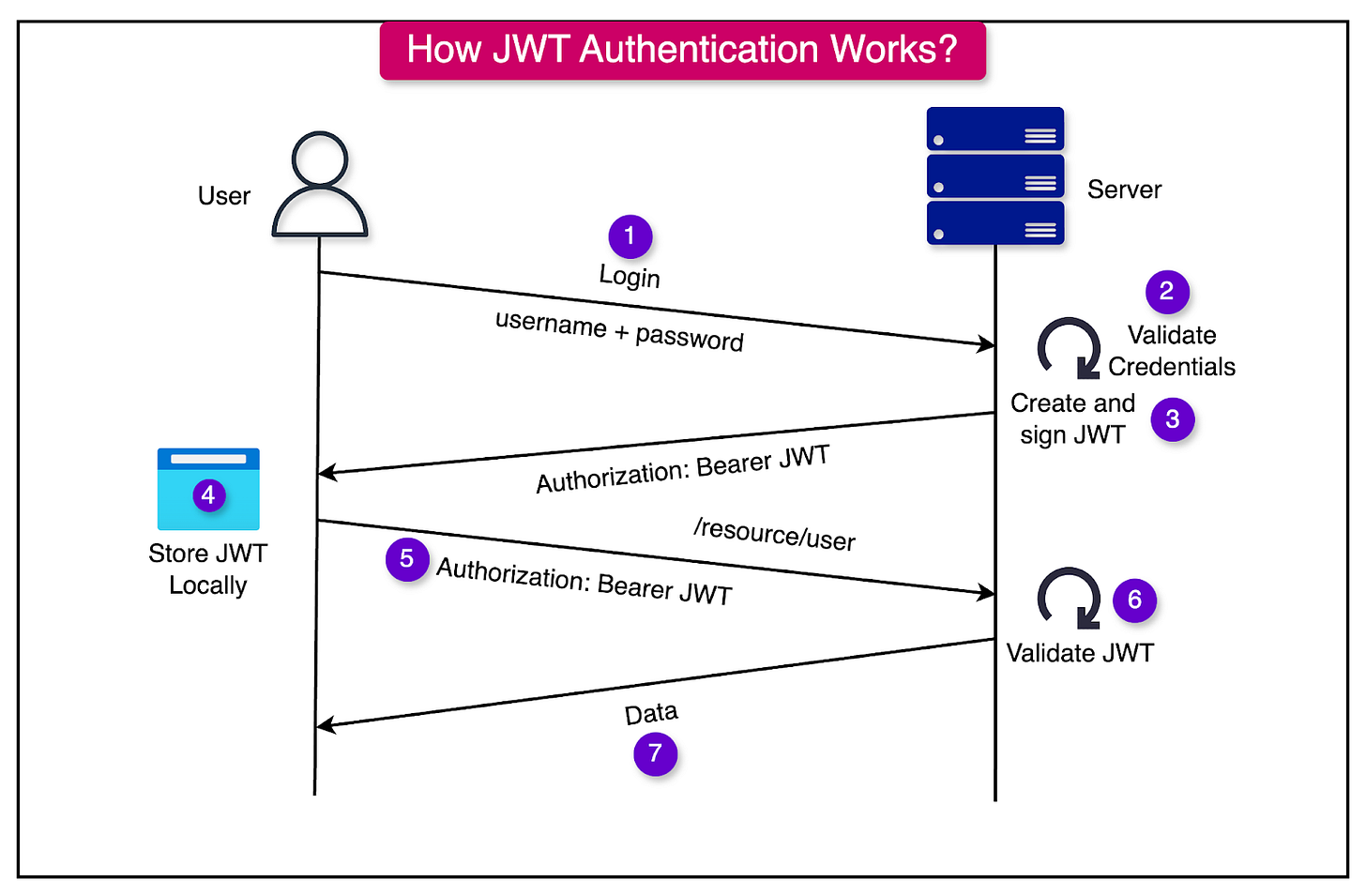

Let’s look at the various steps in which JWT helps with authentication:

Token Issuance:

After a user logs in, the server authenticates the credentials and generates a JWT containing claims about the user (e.g., user ID, roles, etc.).

The JWT is signed using a secret key (symmetric signing) or a private key (asymmetric signing).

The signed token is sent to the client, typically in the response body or as a cookie.

Including JWT in Requests: For subsequent requests, the client includes the JWT in the Authorization header as a Bearer token. The same token can al

Token Validation: The server validates the token by verifying the signature and checking claims like expiration (exp) or audience (aud). If the token is valid, the server allows access to the requested resource.

See the diagram below that shows this process on a high-level:

The Stateless Nature of JWT

JWTs are stateless, meaning:

The server does not need to store session data. All user-related information is contained within the token.

The server only needs the signing key to validate the token, making it ideal for distributed systems where multiple services interact.

Advantages of JWT

JWTs have some key advantages when it comes to distributed systems:

Scalability: Stateless tokens eliminate the need for centralized session storage, making JWTs suitable for microservices or distributed architectures.

Compact and Portable: Base64-encoded format allows JWTs to be easily transmitted in HTTP headers or stored in cookies.

Cross-Domain Authentication: JWTs are useful for Single Sign-On (SSO), allowing authentication across different domains or services.

Security: JWTs are signed, ensuring data integrity and authenticity.

Disadvantages of JWT

The disadvantages of JWT are as follows:

Token Theft: If a JWT is stolen (e.g., through XSS), it can be used until it expires. It can be mitigated using HTTPS to encrypt communications. Also, the tokens should be stored securely using HttpOnly cookies.

Expiration Management: JWTs are typically short-lived. Once issued, they cannot be revoked unless additional measures (e.g., blacklists) are implemented. This problem can be mitigated by implementing refresh tokens to issue new JWTs without requiring re-login.

Token Size: Embedding too much data in the payload can increase token size, affecting performance.

Revoking Access: Unlike sessions, we cannot revoke a JWT for a particular user. To support this feature, we need to store a separate list of revoked tokens and check whether the token received is part of this list.

PASETO: A Secure Alternative to JWT

PASETO, short for Platform-Agnostic Security Tokens, is a modern alternative to JWTs. It is designed with a focus on security, simplicity, and cryptographic best practices.

PASETO addresses some common vulnerabilities and misuse issues associated with JWT while maintaining the flexibility needed for a wide range of authentication and authorization scenarios.

Unlike JWT, which allows flexibility in algorithm choice (sometimes leading to insecure configurations), PASETO enforces the use of strong, cryptographically sound algorithms, reducing the risk of vulnerabilities from misconfiguration.

How PASETO Differs from JWT?

Let’s look at the key points of difference between the two:

Stronger Cryptographic Guarantees:

PASETO enforces the use of strong, modern cryptographic algorithms, eliminating the risk of insecure or outdated algorithms.

For example, while JWT allows developers to use weak algorithms (e.g., HS256 or even the infamous none algorithm), PASETO restricts the choice to robust algorithms like:

AES-GCM for encryption (symmetric).

Ed25519 for signing (asymmetric).

Simplified Design:

PASETO is opinionated and removes unnecessary complexity by avoiding algorithm negotiation, which is a source of vulnerabilities in JWT.

Unlike JWT, it eliminates the risk of algorithm confusion by explicitly specifying which cryptographic algorithms should be used for each version and purpose.

Readable and Secure:

PASETO tokens are local (encrypted) or public (signed), ensuring that sensitive data is either securely encrypted or signed for authenticity.

JWT tokens are always visible in plaintext, even when signed, making them prone to unintentional information leaks.

Built-in Mitigations Against Common Vulnerabilities: By design, PASETO mitigates risks like algorithm tampering, a common issue with JWT.

Structure of a PASETO

A PASETO token consists of three or four main components, depending on whether it is a local token or a public token. Just like JWT, these components are separated by dots and are as follows:

Version: Indicates the version of the PASETO protocol being used. For example, the version v1 uses older cryptographic standards whereas version v2 uses modern, secure cryptographic standards.

Purpose: Specifies the type of the token–whether it is meant to be encrypted or signed. The options are local (encrypted token) and public (signed token).

Payload: Contains the actual data or claims within the token. For local tokens, the payload is encrypted and appears as an opaque Base64Url-encoded string. For public tokens, the payload is plaintext and Base64Url-encoded.

Footer: Contains the optional metadata not included in the payload such as audience(aud) or issuer (iss).

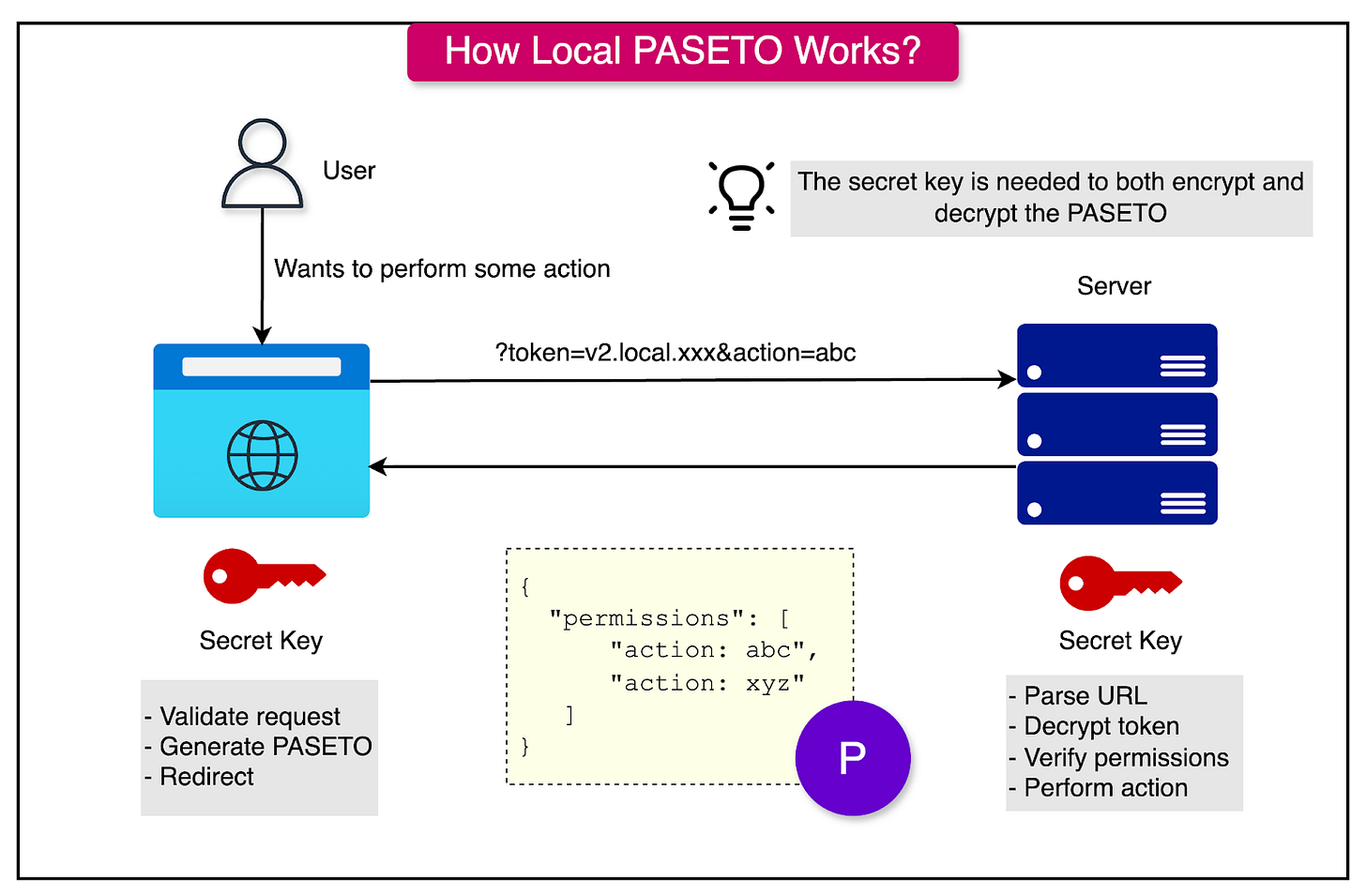

Local PASETO vs Public PASETO

Local PASETO tokens are encrypted, ensuring the confidentiality of the data contained within the token. They are intended for scenarios where sensitive information must remain hidden from unauthorized parties.

They use symmetric encryption algorithms to ensure the payload is confidential. Only parties with the shared secret key can decrypt and access the token’s contents. See the diagram below:

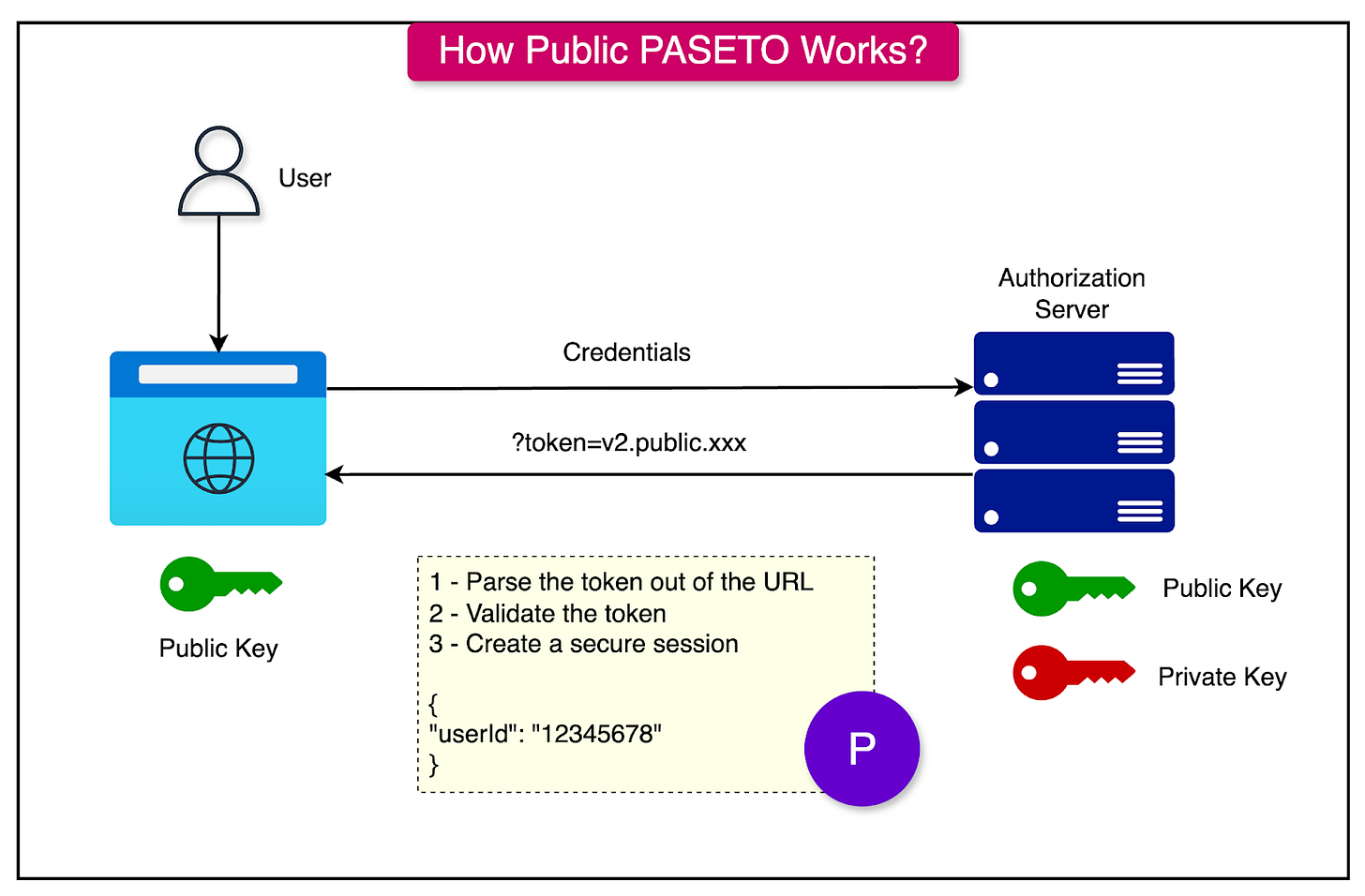

Public PASETO tokens, on the other hand, are signed. They ensure the integrity of the data but not its confidentiality. These tokens are transparent and can be read by anyone, but only verified by the holder of the signing key. In other words, the token cannot be altered without invalidating the signature.

They use asymmetric cryptography (for example, ED25519) to sign the token. The public key is used to verify the token, while the private key is used to sign it. They are suitable for scenarios where the payload needs to be read by clients but must remain tamper-proof.

See the diagram below

Advantages of PASETO

The main advantages of PASETO are as follows:

Security by Design: No insecure or deprecated algorithms, ensuring that developers cannot make dangerous cryptographic choices. It avoids pitfalls like JWT’s none algorithm or insecure HS256 use.

Ease of Use: The absence of algorithm negotiation simplifies implementation, reducing the risk of misconfiguration.

Encryption Support: PASETO supports encrypted tokens (local tokens), providing both confidentiality and integrity, whereas JWT tokens are only signed and always visible.

Forward Compatibility: PASETO is versioned (e.g., v1, v2), ensuring that improvements in cryptographic practices can be incorporated while maintaining backward compatibility.

Cross-Platform: As the name implies, PASETO is platform-agnostic and works seamlessly across different programming languages and systems.

Challenges of PASETO

PASETO also has some challenges worth considering:

Limited Adoption: Compared to the ubiquitous JWT, PASETO is relatively new and less widely adopted. This means fewer libraries, tools, and community support are available.

Learning Curve: Developers familiar with JWT may need time to understand and adapt to PASETO’s principles and features.

Ecosystem Maturity: While the PASETO standard is well-defined, its ecosystem lacks the extensive middleware and framework integrations available for JWT.

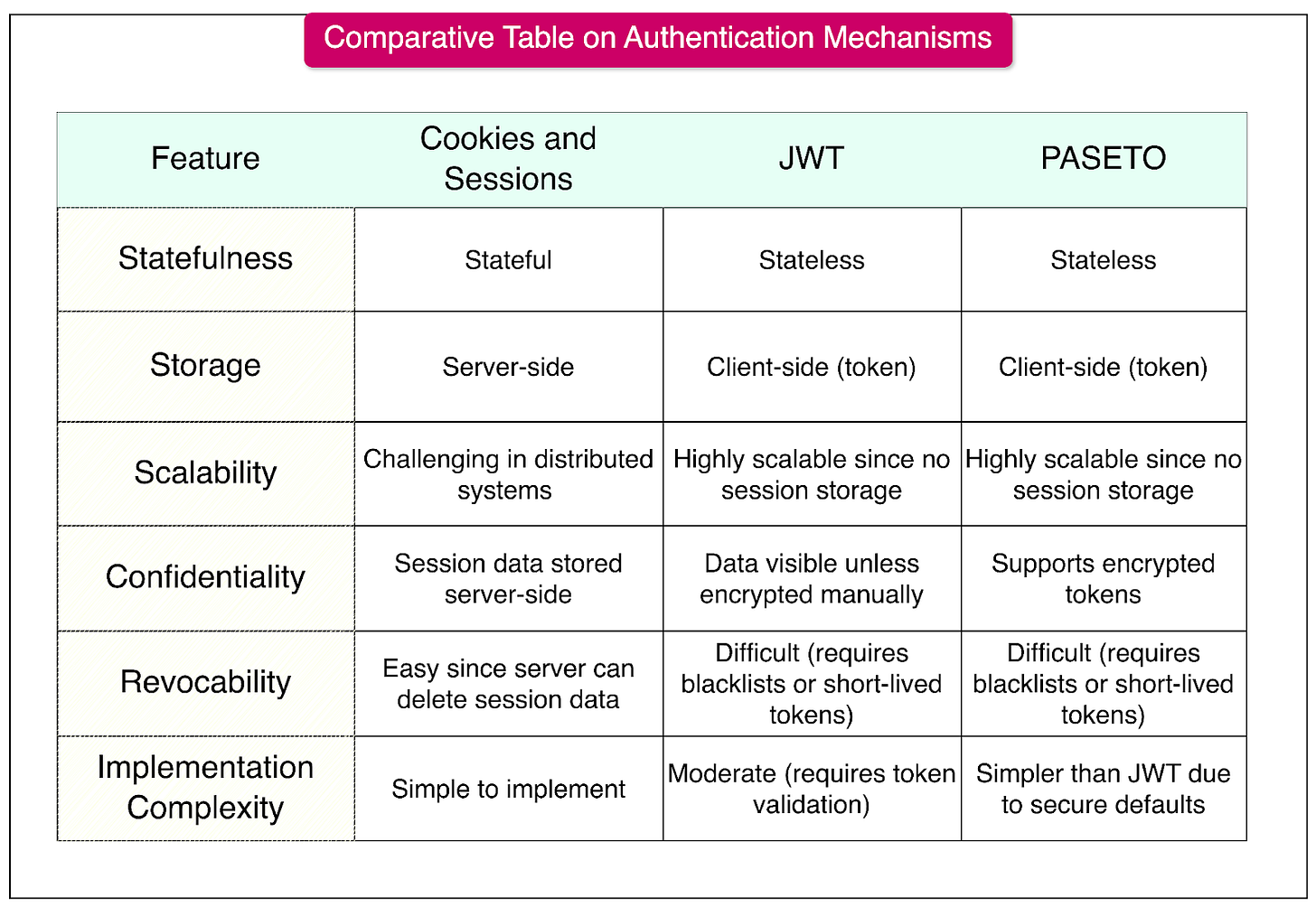

Comparative Analysis

Below is a detailed comparative table of Cookies and Sessions, JWT, and PASETO, focusing on their core characteristics, security considerations, and ideal use cases.

Best Practices for Implementing Secure Authentication

While the various approaches have pros and cons, several best practices can help implement secure authentication.

Here are the most important ones:

Use HTTPS: It ensures that all data exchanged between the client and server is encrypted, protecting against man-in-the-middle attacks. Some ways to accomplish this are:

Configure HTTPS for all environments (development, staging, and production).

Redirect all HTTP requests to HTTPS.

Use strong TLS versions (for example, TLS 1.2 or 1.3).

Enforce Strong Password Policies: Weak passwords are easy targets for brute-force or credential-stuffing attacks. To implement this:

Require a minimum length (e.g., 12+ characters).

Include complexity rules (uppercase, lowercase, numbers, special characters).

Check passwords against known breached password lists.

Implement Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): Adds an extra layer of security by requiring additional verification methods beyond passwords. This can be done by:

Time-based one-time passwords (TOTP) via apps like Google Authenticator.

SMS-based OTPs as a fallback, though less secure than app-based methods.

Push notifications for MFA via secure mobile apps.

Secure Token Management: Tokens are an important component of modern authentication, and their compromise can lead to unauthorized access. Some tips to handle tokens are as follows:

Use short-lived tokens with a defined expiration (exp) claim.

Implement refresh tokens for reauthentication without exposing the primary credentials.

Store tokens securely.

Use HttpOnly cookies to prevent access by JavaScript.

Avoid storing tokens in localStorage or sessionStorage.

Rotate and revoke tokens when necessary (for example: on password reset or logout).

Use Secure Cookie Settings: Cookies are often used to store session or authentication data and are vulnerable to theft. Some tips to secure the cookies are as follows:

Set the HttpOnly flag to prevent access via JavaScript.

Use the Secure flag to ensure cookies are only sent over HTTPS.

Implement the SameSite attribute to mitigate CSRF attacks:

SameSite=Strict for high-security applications.

SameSite=Lax for applications needing limited third-party cookie usage.

Summary

In this article, we’ve taken a detailed look at various authentication mechanisms and their advantages and disadvantages.

Let’s summarize our learnings in brief:

Authentication ensures that only authorized users gain access to an application’s resources.

Cookies and sessions are a stateful authentication mechanism where session data is stored on the server and referenced via a client-side cookie.

Sessions are ideal for applications requiring strict server-side control over user data but may face scalability challenges in distributed systems.

JSON Web Tokens is a stateless, self-contained authentication method that stores all user data within the token.

JWTs are highly scalable and suitable for distributed systems but require careful handling to mitigate token theft and manage expiration effectively.

PASETO improves upon JWT by enforcing strong cryptographic defaults and eliminating algorithmic vulnerabilities.

PASETO simplifies secure token implementation by avoiding the risks of misconfiguration present in JWTs.

HTTPS is essential for securing all communication and preventing man-in-the-middle attacks on sensitive data.

Very nice article, but it seems incomplete in some areas:

```

Including JWT in Requests: For subsequent requests, the client includes the JWT in the Authorization header as a Bearer token. The same token can al

```

Excellent article on modern authentication, but it seems incomplete in some areas like below:

''' Including JWT in Requests: For subsequent requests, the client includes the JWT in the Authorization header as a Bearer token. The same token can al'''