Non-functional requirements (NFRs) are as critical as functional requirements because they define a system's qualities and operational parameters.

While functional requirements specify what a software product should do (for example, “users must be able to log in”), non-functional requirements define how well it must accomplish these tasks under real-world conditions (for example, “the login process should respond within two seconds under peak load” or “all user credentials must be encrypted and stored securely”).

Together, functional and non-functional requirements create a foundation for building great software systems.

NFRs are essential for the following reasons:

Quality of Service: NFRs like response time, availability, and usability directly affect the user’s perception of quality. A system that fulfills its functional requirements but is slow, constantly crashes, or is difficult to use can undermine user trust and satisfaction.

System Stability: Requirements such as reliability, fault tolerance, and recoverability help maintain stable operation even when part of the system fails. Without these, unhandled errors can escalate into large-scale outages.

Security and Compliance: Security-related NFRs dictate how data is protected, how access is controlled, and how audits are conducted. Neglecting these can lead to breaches, legal consequences, or reputational damage.

Scalability and Performance: Requirements for throughput, capacity, and resource utilization ensure the software can handle growth in users or data. If not addressed from the start, scaling can become prohibitively expensive or technically challenging later on.

Maintenance and Evolution: Maintainability, testability, and modularity requirements determine how easily bugs can be fixed, features added, or adaptations made to changing environments. Overlooking them can lead to ballooning technical debt, slowing down future development.

In short, non-functional requirements are not mere “nice-to-haves” but essential components that ensure a software system truly meets user expectations and withstands real-world challenges.

In this article (Part 1), we’ll look at the differences between functional and non-functional requirements. Then, we’ll explore the various trade-offs in NFRs and their architectural impact on building systems.

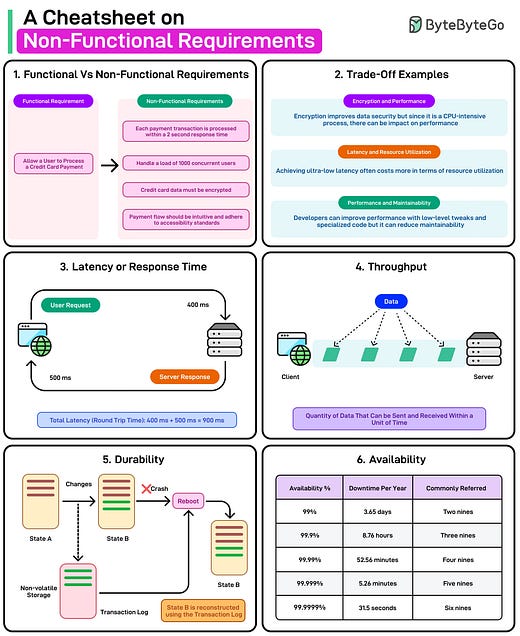

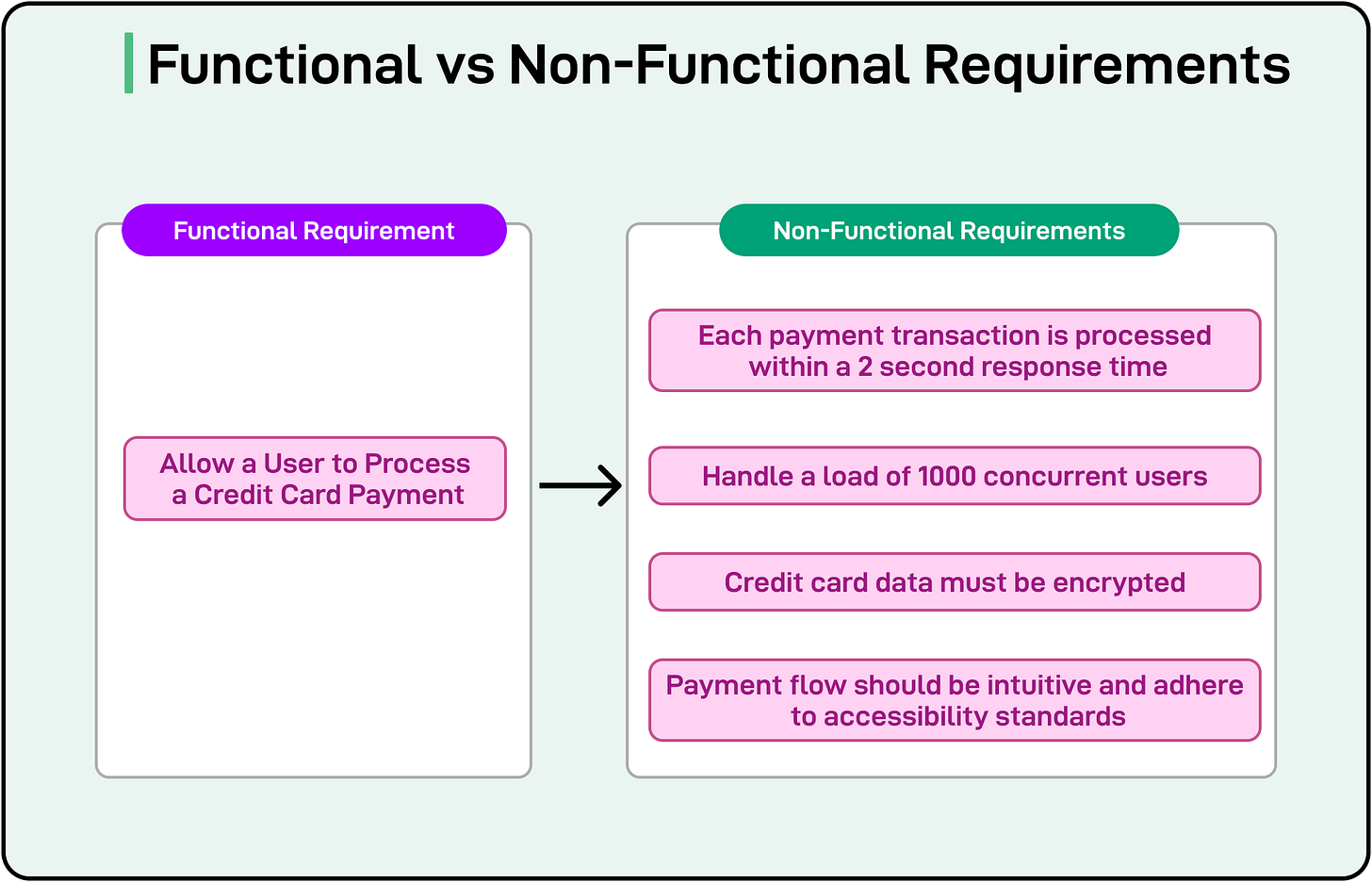

Functional vs Non-Functional Requirements

As mentioned, functional requirements describe the features and behaviors the system must exhibit. They focus on the core tasks or processes the software must execute to achieve a specific objective. These requirements often originate from stakeholder needs or user stories.

For example, a payment system might have a functional requirement that states: “The system must allow a user to enter credit card details and process a payment.”

This requirement describes the “what”. The system needs to handle transactions using credit card information. It outlines the essential functionality but does not detail the operational conditions under which this function must be performed effectively or securely.

Non-functional requirements define the attributes and constraints that shape the system's user experience, performance, security, and maintainability. They dictate how well the system should perform the defined functions, especially under real-world conditions such as high user loads or partial failures.

A system that meets all functional requirements (i.e., it can technically do everything it’s supposed to) can still fail if it doesn’t satisfy critical non-functional standards.

Let’s compare them side by side for a payment system:

Functional Requirement: Let’s say the functional requirement is to “allow a user to process a credit card payment.” The system will fulfill this requirement if it completes a payment and updates the transaction history.

Non-Functional Requirements: Some NFRs for such a payment system can be as follows:

Ensure each payment transaction is processed within a 2-second response time under a load of up to 1,000 concurrent users.

Credit card data must be encrypted and compliant with payment industry regulations. The system must enforce multi-factor authentication for administrator logins.

Design the payment flow so that it is intuitive, with minimal steps, and adheres to accessibility standards for visually impaired users.

In other words, while the system may technically function by accepting a credit card number and processing a payment, ignoring the non-functional aspects can lead to slow processing, security gaps, and a poor user experience.

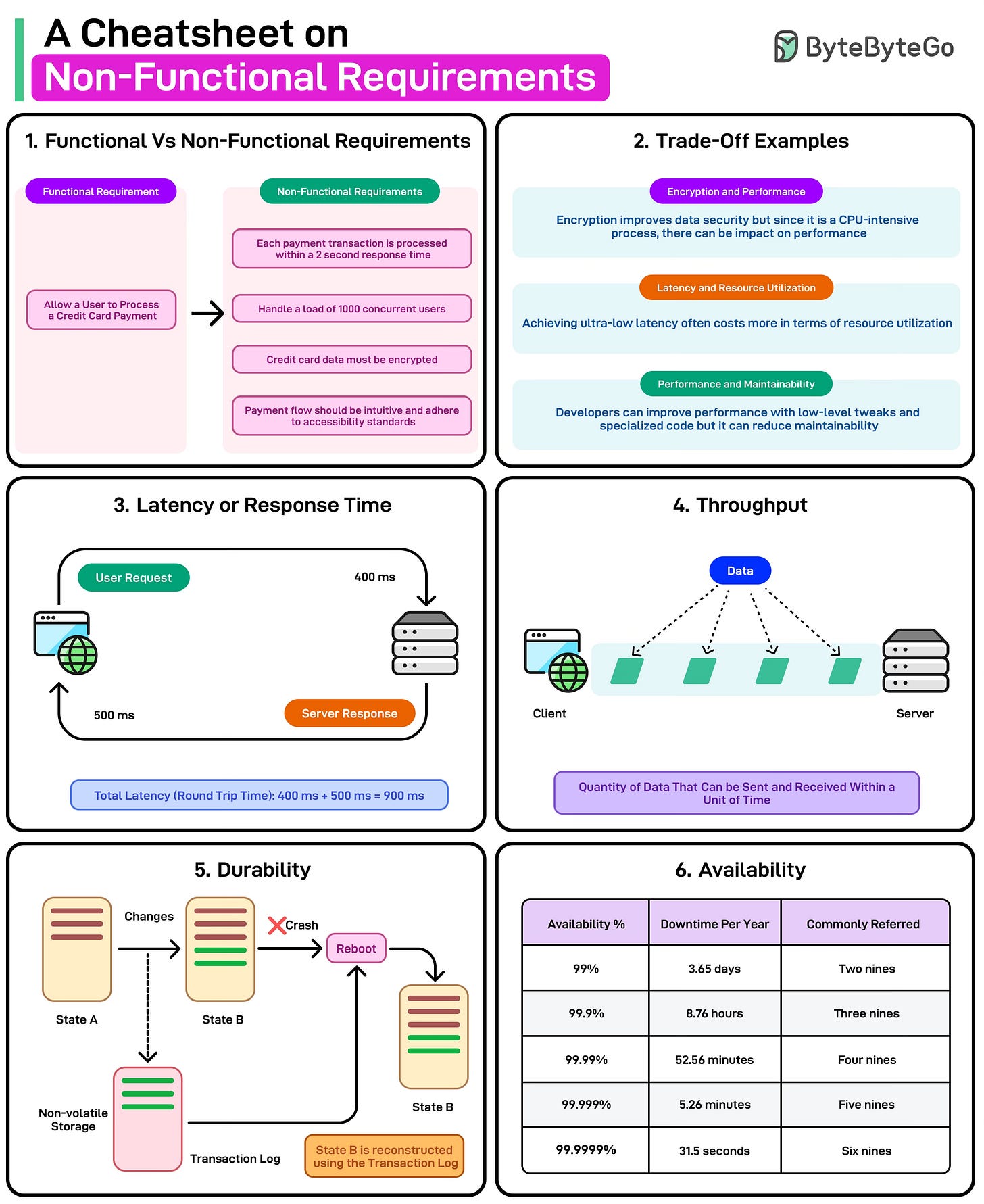

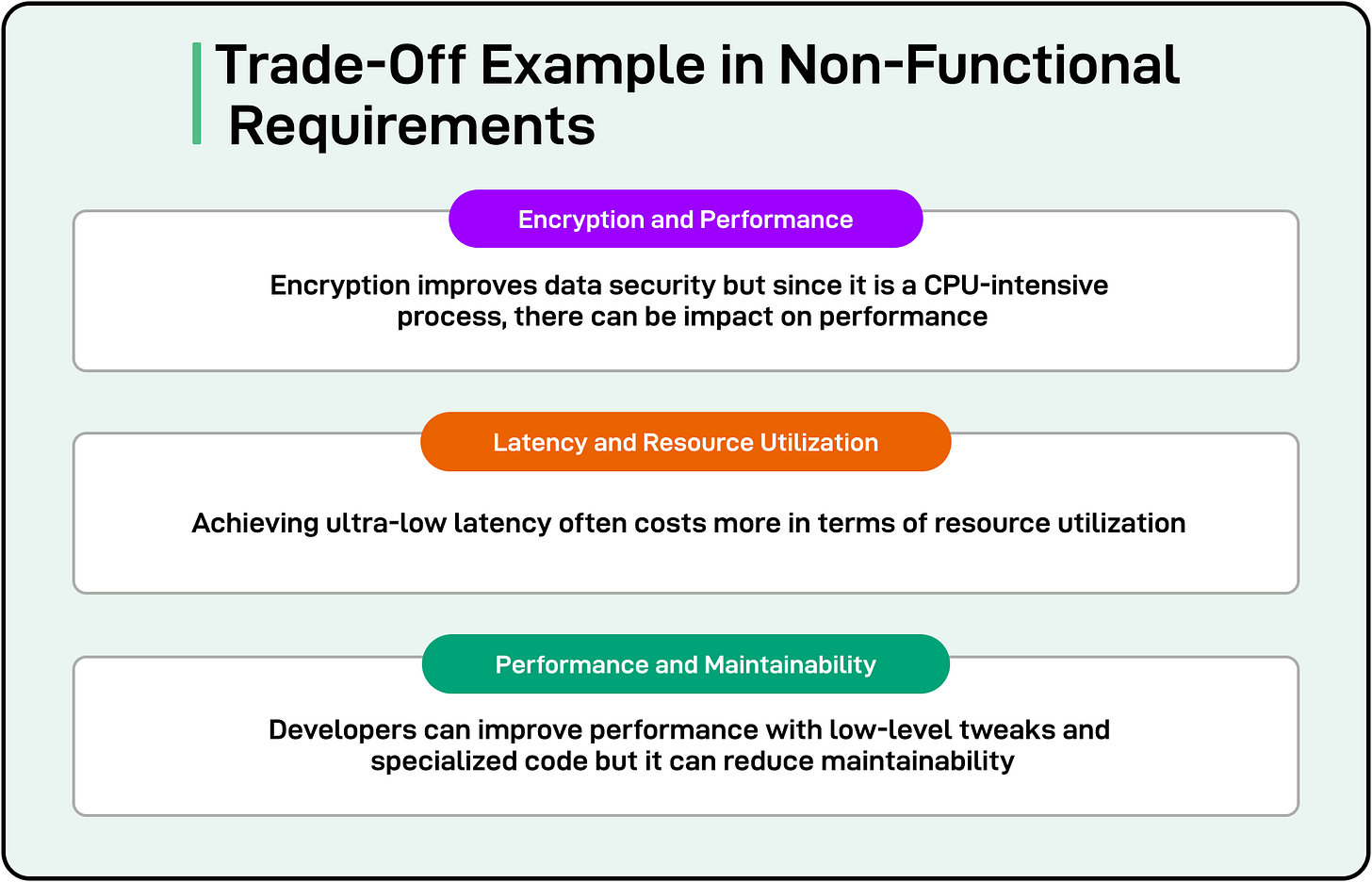

Trade-Offs in Non-Functional Requirements

Non-functional requirements (NFRs) are seldom isolated.

Optimizing for one often has a ripple effect on others. This interdependency stems from the fact that system resources (time, memory, processing power, etc.) and design trade-offs (complexity, maintainability, etc.) are finite. Enhancing a single non-functional aspect can harm others.

Let’s look at a few obvious trade-offs that developers face when dealing with non-functional requirements:

1 - Encryption and Performance

When an application adopts robust encryption algorithms for data at rest or in transit, it improves security by making unauthorized access or interception more difficult.

However, encrypting and decrypting data are CPU-intensive operations.

Under high concurrency, these operations can add noticeable latency to data read/write cycles or API requests. If the infrastructure is not scaled or optimized to handle the extra load, response times may increase, affecting user satisfaction and overall throughput.

Some strategies to balance this trade-off are as follows:

Hardware Acceleration: Use specialized hardware or CPU instructions for encryption/decryption to mitigate the performance impact.

Selective Encryption: Encrypt only the most sensitive data fields to reduce overhead.

Caching: Cache decrypted content or use secure sessions to minimize repeated encrypt-decrypt cycles, but ensure proper key management to maintain security.

2 - Low Latency and Resource Utilization

For high-frequency trading or real-time analytics, systems are designed to respond in milliseconds, with near-zero delays.

Achieving ultra-low latency often requires high-end hardware, faster network connections, and specialized architectures (for example, in-memory databases, and distributed caching). These come at a significant cost. Additionally, more sophisticated setups (like active-active deployments across multiple regions) can introduce operational complexity and increased maintenance overhead.

Some strategies to balance this trade-off are as follows:

Scaling vs. Optimization: Before scaling the infrastructure, optimize code paths, reduce unnecessary network hops, and implement efficient data structures.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Quantify the return on investment for ultra-low latency. For some use cases, a slight increase in response time (such as from 10ms to 50ms) may be acceptable if it reduces costs substantially.

Feature Trade-offs: Temporarily disable non-essential features or logging in high-throughput paths to minimize overhead.

3 - Performance vs Maintainability

Sometimes, developers optimize software with low-level tweaks or non-standard data structures to squeeze out maximum performance.

However, specialized code can become harder to read, test, and modify. Developer onboarding takes longer, and routine changes might introduce regressions if the optimized sections aren’t well-documented or tested.

Some strategies to balance this trade-off are as follows:

Documented Patterns: Maintain detailed internal documentation explaining optimization decisions and how they affect system behavior.

Incremental Optimization: Start with a clean, maintainable design. Optimize only after profiling and identifying real bottlenecks, rather than preemptively over-optimizing.

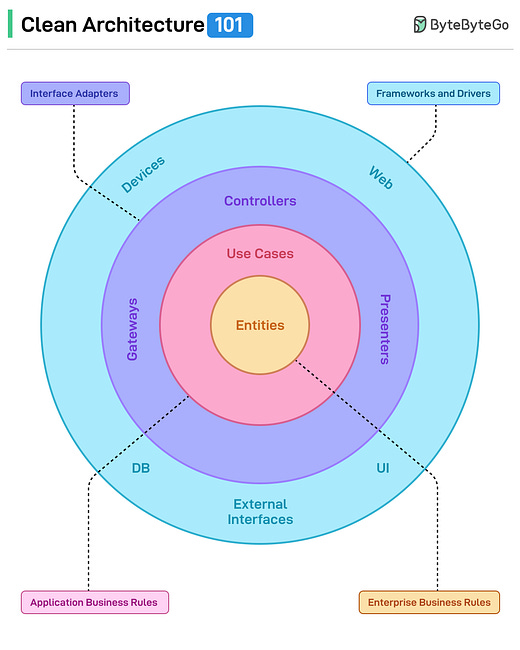

Design for Change: Employ modular architecture so high-performance components are isolated, limiting the spread of complexity across the entire codebase.

Architectural Impact of NFRs

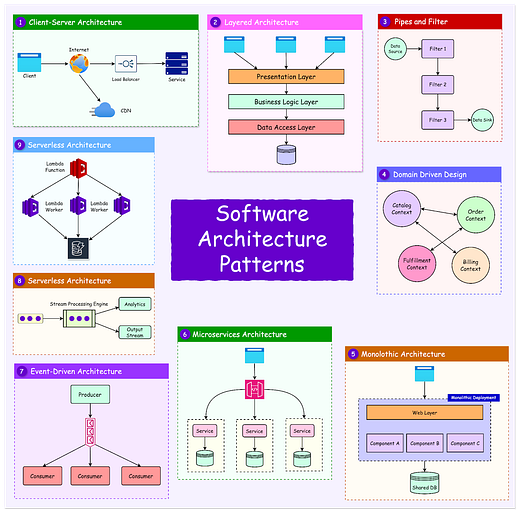

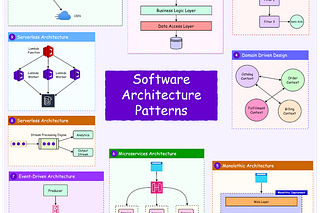

Non-functional requirements (NFRs) often determine which architectural style best suits a particular system.

Below are several ways in which NFRs influence architectural decisions, along with examples showing how certain patterns can address different priorities.

High Availability: Redundancy and Load Balancing

When availability is a top priority, teams often employ architectures that incorporate redundancy, failover mechanisms, and load balancing.

High-availability designs typically introduce more infrastructure (load balancers, monitoring, auto-scaling). This can complicate deployment and maintenance processes. Also, redundant instances and failover sites increase operational expenses.

Some examples of such architectural styles are as follows:

Microservices with Redundancy

Event-Driven or Reactive Systems

Monolithic Architecture with Clustering

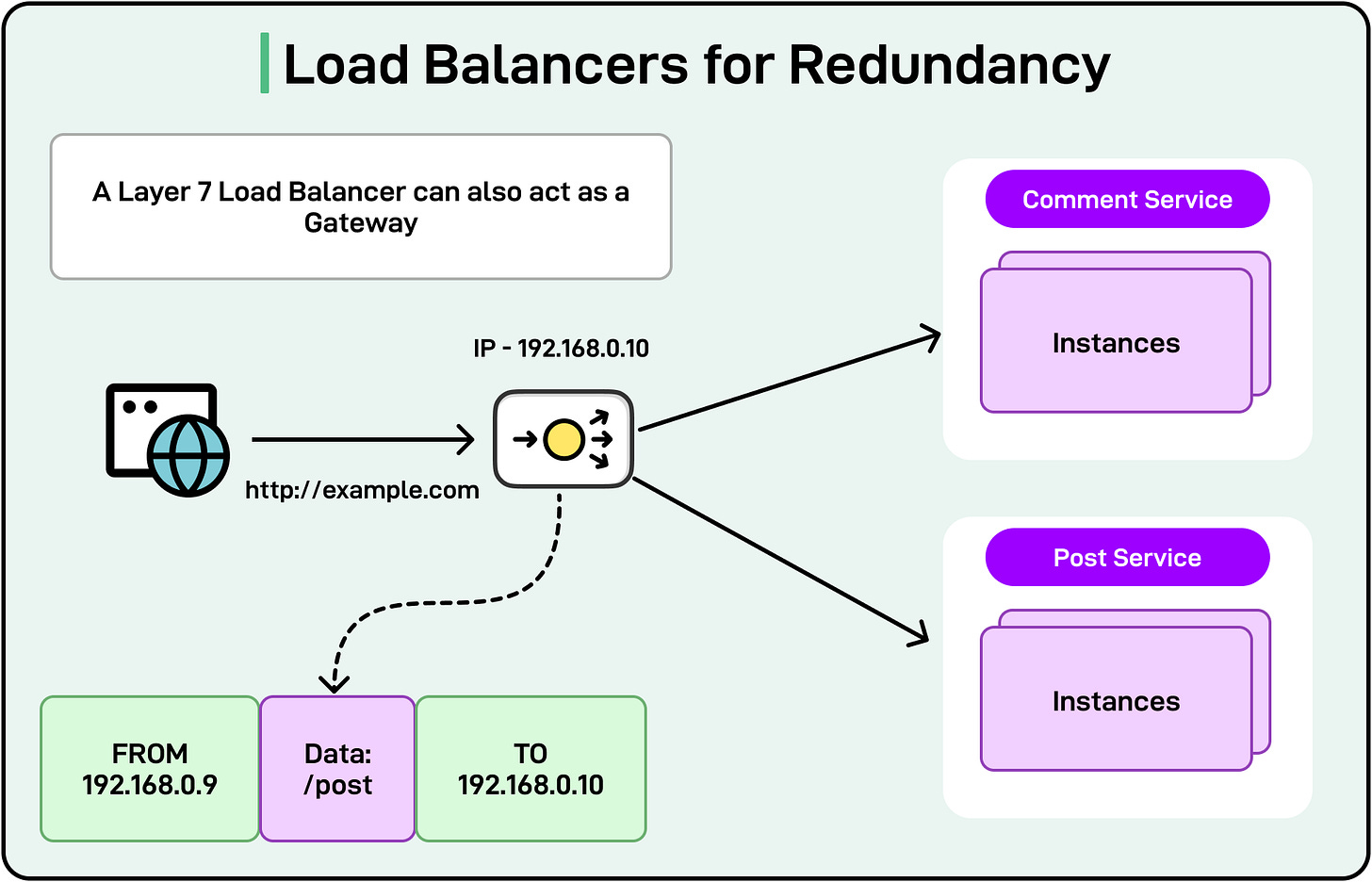

Each microservice instance can be deployed in multiple geographic locations or multiple containers within the same environment. Load balancers distribute incoming requests across these instances. If one instance fails, traffic is automatically rerouted to healthy ones, enhancing overall uptime.

See the diagram below that shows a Layer 7 load balancer that can also act like an API Gateway.

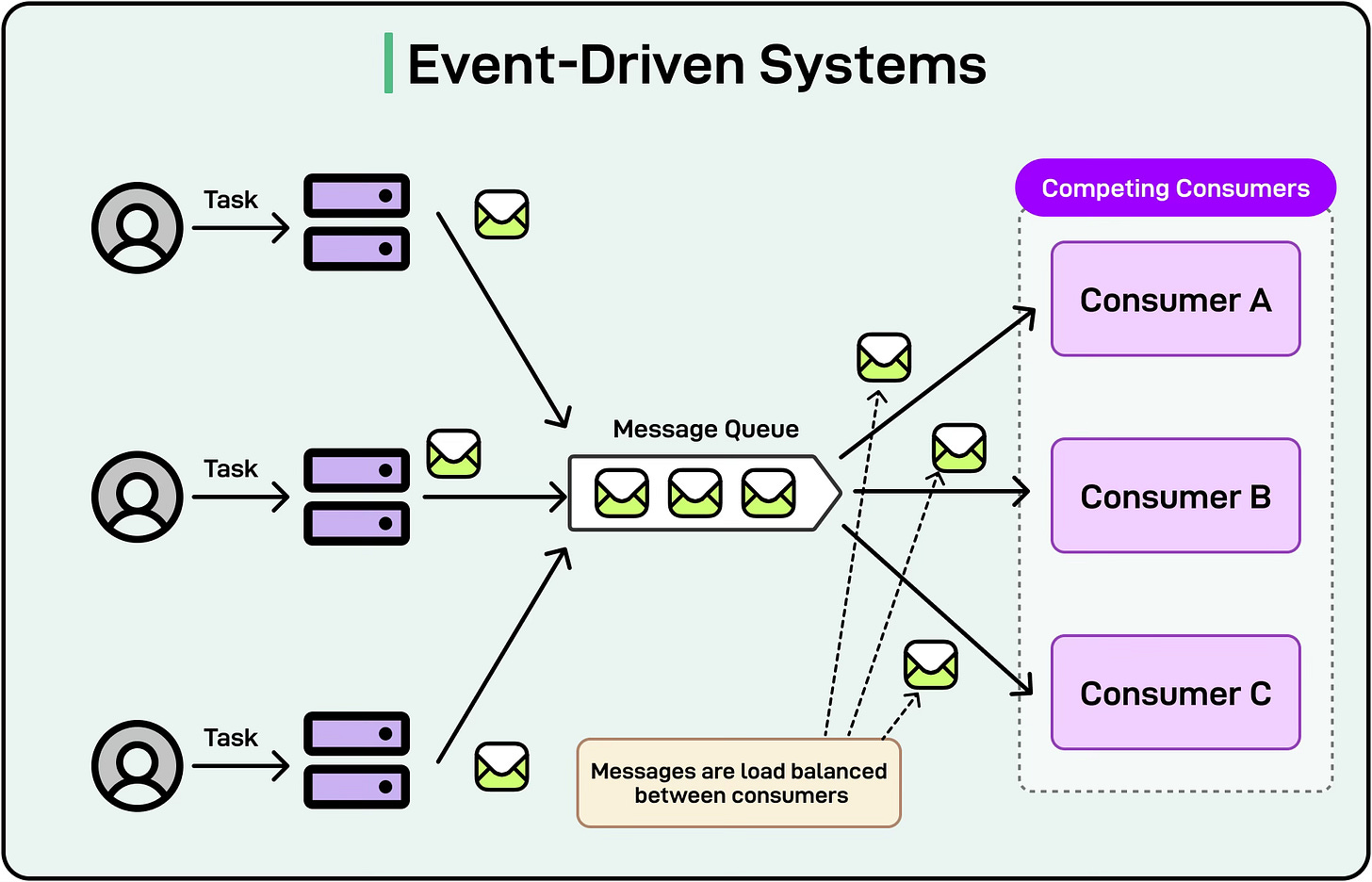

Systems designed around events (for example, using message brokers like Kafka or RabbitMQ) can be highly fault-tolerant. Events are stored in queues, so if a consumer service temporarily goes down, it can catch up when it restarts. This architecture minimizes downtime, as the system can continue processing events even when some components are being updated or replaced.

See the diagram below that shows an example of an event-driven implementation that implements the competing consumer pattern.

Lastly, even a monolithic application can achieve high availability by running multiple instances behind a load balancer. However, a monolith may have a larger blast radius if a critical part of the code encounters a failure, whereas microservices can isolate failures to individual services.

Multiple Calls and Performance: Microservices and Monoliths

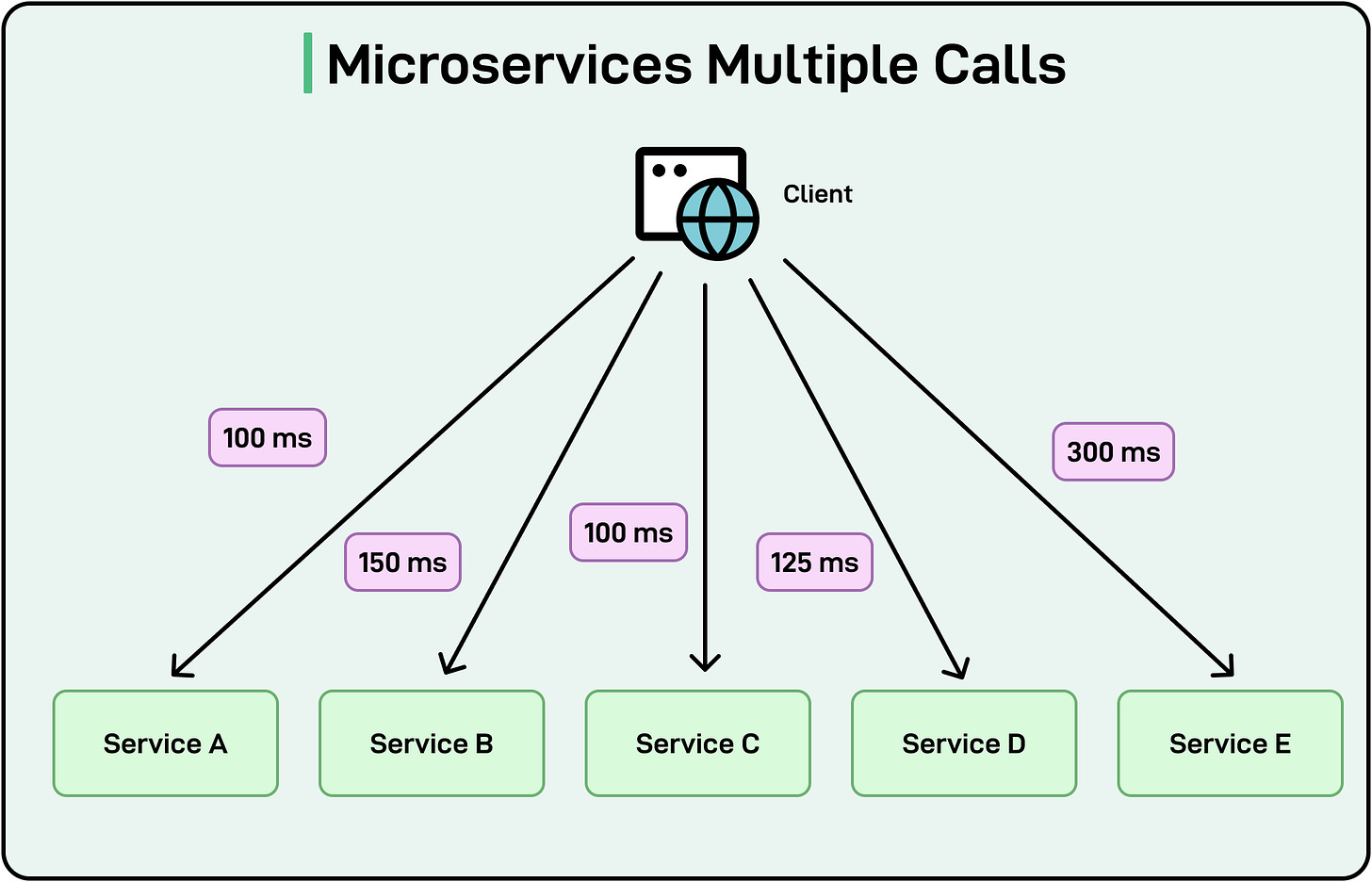

In a microservices architecture, a single user request might result in multiple internal service calls to gather data from different services. In such a scenario, one failing service doesn’t necessarily bring down the entire system. This improves resilience (an important NFR) because each service can be isolated, monitored, and recovered independently.

But while this design can enhance scalability and maintainability (we can independently deploy and scale each microservice), it can also increase latency and complexity if not optimized.

For example, if the aggregator or the client makes sequential calls to multiple services to fulfill a request, the latency of each call is added to the total. Even in the case of parallel requests, the overall response time is roughly determined by the slowest (highest-latency) service. If one service is significantly slower than the others, the entire user request is effectively blocked until that service returns or times out.

As simple mitigation, strategies like caching and circuit breakers can reduce latency. Also, service orchestration or API gateways can handle aggregated responses to limit the client’s number of calls.

On the other hand, a monolithic application typically involves fewer network hops (most calls are in-process), which can result in lower latency under certain conditions.

This means that performance for intra-application communication might be high, but availability and scalability can be more challenging to improve without comprehensive refactoring. Also, deploying and monitoring one big application is simpler in some ways, but if part of the monolith fails or becomes a performance bottleneck, it can affect the entire system.

Other Architectural Styles

Some other architectural styles that may be driven by NFRs are as follows:

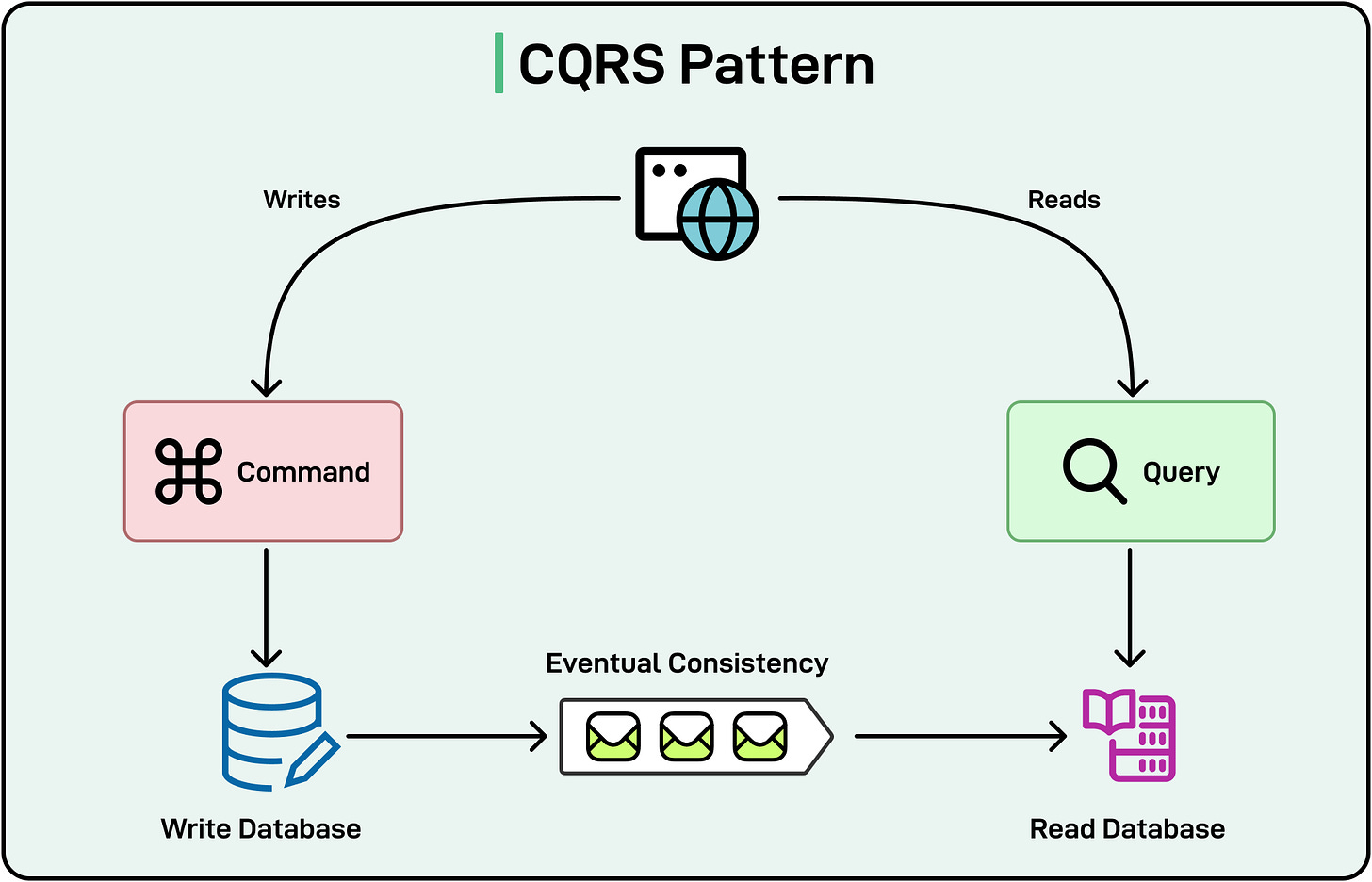

Event-Driven/CQRS: Often chosen when scalability and performance are paramount for read and write operations. By segregating read and write models, systems can handle large volumes of data with different consistency requirements.

Serverless/Function-as-a-Service: Ideal when cost efficiency and elastic scaling are top priorities. Functions scale automatically based on incoming requests, though cold-start issues and vendor lock-in can become factors.

See the diagram below that shows the CQRS pattern:

Matching Architecture to Project-Specific NFRs

Choosing the right architectural style is a balancing act among multiple non-functional priorities:

Performance: Can lean toward monolith or carefully orchestrated microservices to minimize network overhead.

Availability and Fault Tolerance: Often favors microservices with redundancy and event-driven approaches.

Modifiability and Maintainability: Modular or plugin-based designs, or well-structured microservices.

Security: This could require layered security controls and well-defined service boundaries, common in microservice and zero-trust architectures.

Cost Constraints: Serverless or cloud-based microservices can be cost-effective at scale, but can also introduce complexities.

The important point is to evaluate each NFR within the context of the project’s business goals, technical environment, and user expectations before deciding on an architecture.

Summary

We’ve now looked at non-functional requirements and how they impact architectural choices along with some tips on how developers can balance them depending on the project.

Some key learning points are as follows:

Non-functional requirements determine a system's performance in areas such as scalability, response time, performance, security, etc., ensuring it meets quality standards and user expectations beyond mere functionality.

Functional requirements focus on what the system should do, while non-functional requirements define how well it operates under real-world conditions.

Optimizing one NFR (for example, performance) can negatively impact others (for example, maintainability), requiring a balanced approach based on project goals and constraints.

Non-functional needs (like scalability and availability) heavily influence architecture choice. For example, choosing microservices for high availability or plugin-based designs for modifiability.

In the next part of this article, we’ll explore key non-functional requirements in detail.