Distributed systems are collections of independent computing resources that work together to present a unified, cohesive service or application to the user.

Rather than relying on a single powerful machine, these systems spread workloads across multiple nodes, often deployed across different servers, regions, or continents. Building distributed systems is popular because it offers improved scalability, enabling organizations to handle growing traffic by adding more nodes as needed. It also enhances fault tolerance. If one node goes down, the system can often continue serving requests, minimizing downtime and user impact.

However, with these benefits come complexities—what many refer to as the “dark side” of distributed systems.

Coordinating multiple nodes over unreliable networks introduces challenges around data consistency, system synchronization, and partial failures.

Developers must navigate layers of complexity that don’t exist in a single-machine environment, such as dealing with unpredictable message delays and deciding how to handle conflicting writes.

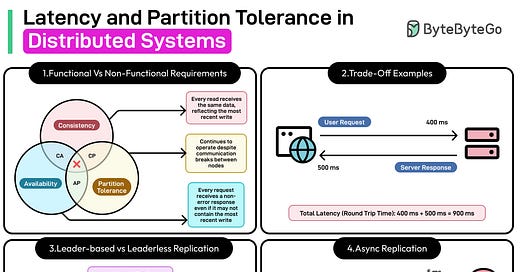

Two critical considerations that consistently arise in distributed systems are latency and partition tolerance.

Latency, or the delay in communication between nodes, can degrade user experience and complicate real-time processing. Partition tolerance, the capacity of a system to continue operating despite communication breakdowns among nodes, highlights the trade-offs between maintaining availability and ensuring data consistency.

In this article, we’ll understand how latency and partition tolerance impact distributed systems and discuss strategies for addressing them effectively.

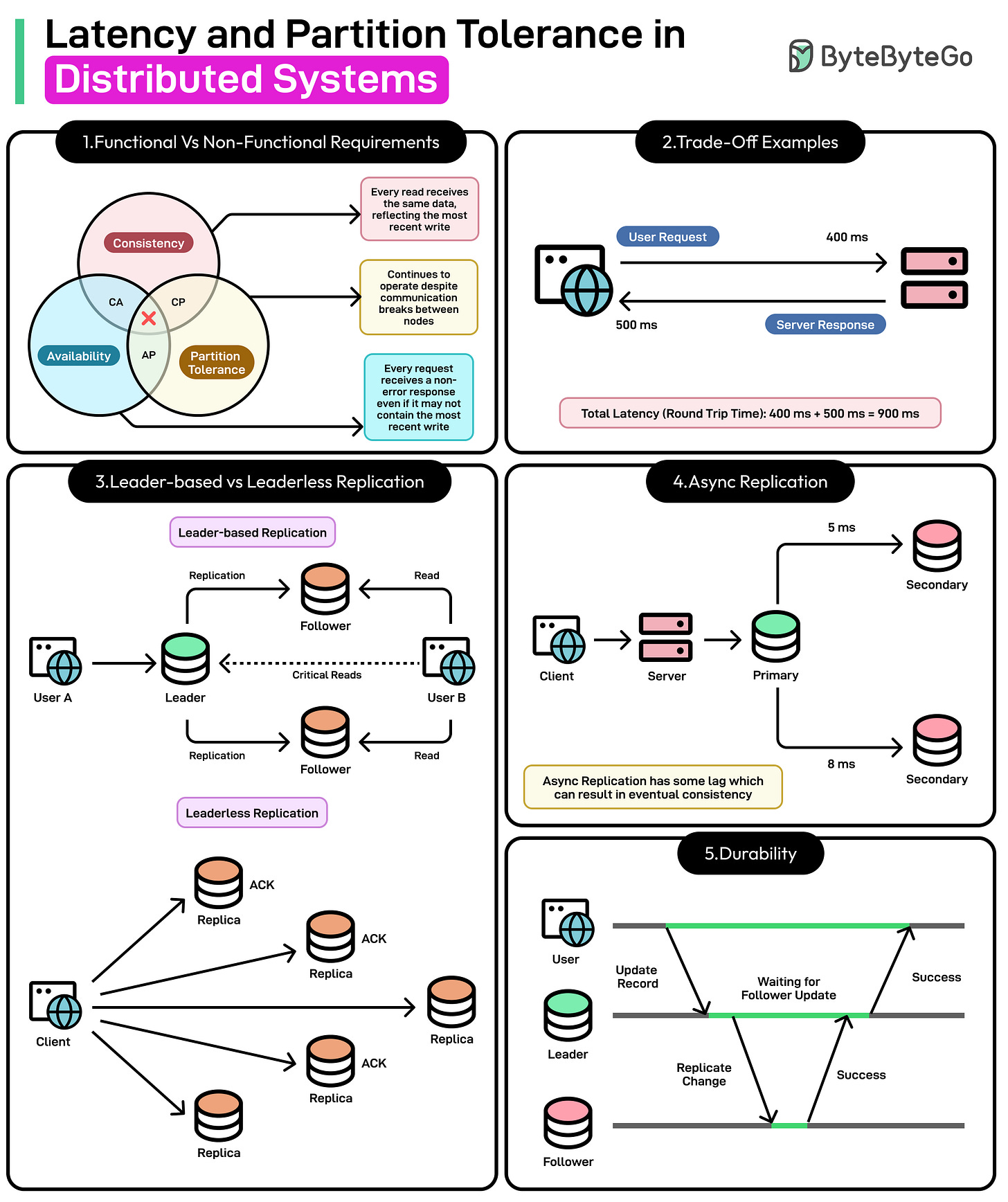

Understanding the CAP Theorem

CAP theorem plays a key role in understanding the implications of a distributed system design.

The CAP theorem asserts that when a network partition occurs, a distributed system can provide either consistency or availability, but not both simultaneously.

The theorem revolves around three core concepts:

Consistency: Every read sees the same data, reflecting the most recent successful write (or an error if that write hasn’t been applied).

Availability: The system processes all read and write requests, ensuring it never fully goes “offline” as long as a node can communicate within the cluster.

Partition Tolerance: The system remains operational despite partial network failures or delays, often referred to as “partitions.”

A common misconception about CAP is that we can “pick any two” out of the three properties in all scenarios.

In reality, partition tolerance is non-negotiable for a truly distributed system. There are always chances of network partitions and we must handle network failures while designing systems. Therefore, we often trade off consistency for availability (or vice versa) under partition conditions.

In practice, real-world systems balance these constraints differently. For example:

Amazon Dynamo (and its variants) prioritizes availability (and therefore partition tolerance), adopting a “write-first, reconcile-later” approach that leads to eventual consistency. This design ensures that even if some nodes become unreachable, the database can continue accepting writes and reads from the remaining nodes.

Apache Cassandra offers tunable consistency levels, letting us choose between stronger consistency guarantees (but slower writes/reads) or higher availability during partitions.

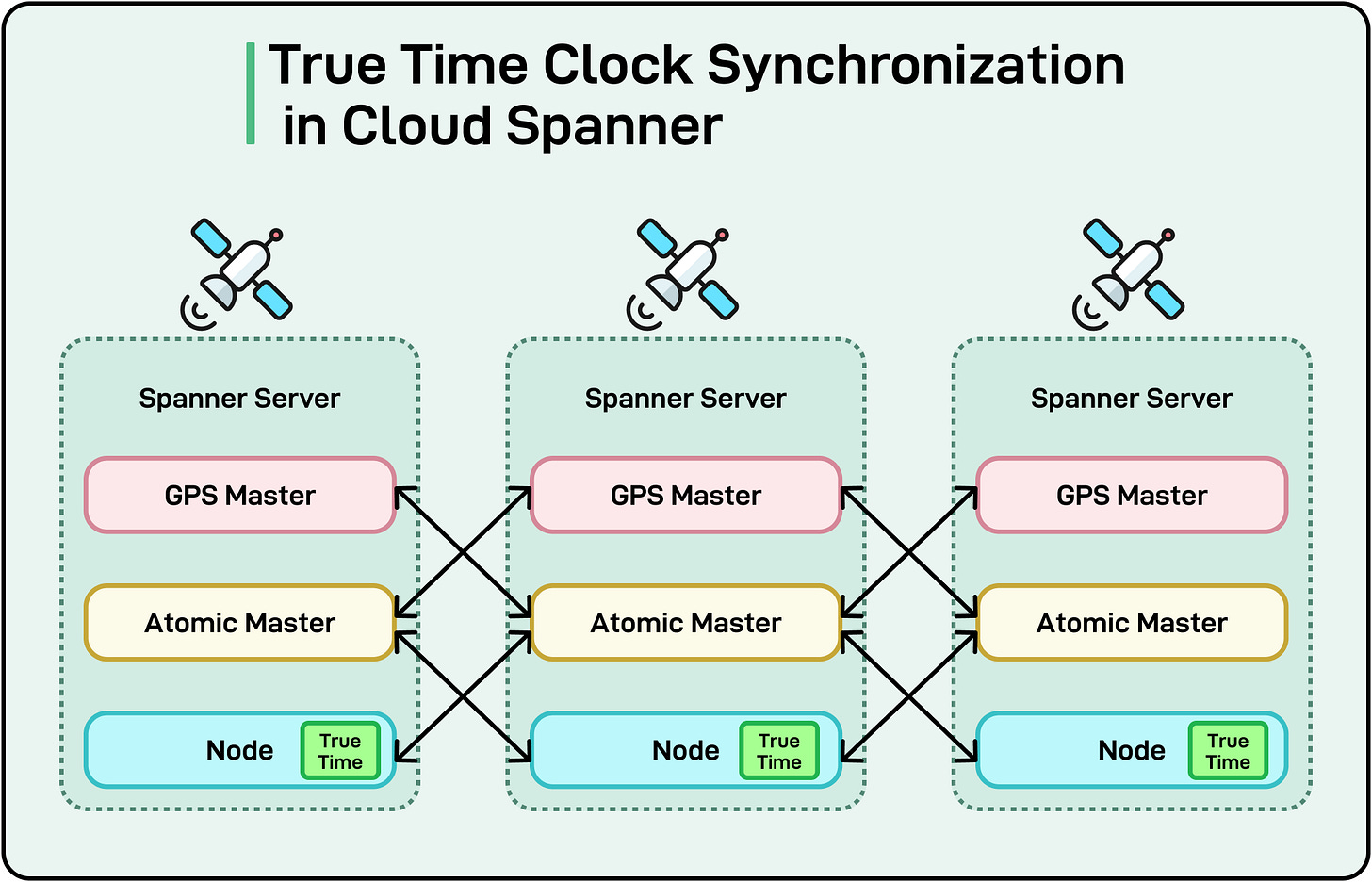

Some database systems advertise “strong consistency and high availability,” which can give the impression that they have somehow escaped the constraints of the CAP Theorem.

Google Cloud Spanner is one such example. It promises global consistency using a combination of atomic clocks and GPS to form its “TrueTime” API, allowing it to tightly synchronize replicas across regions.

At first glance, Cloud Spanner appears to deliver consistency and availability simultaneously across the globe. But in reality, this comes at the cost of very tight infrastructure control (specialized hardware, well-provisioned networks, and precise clock synchronization).

If a genuine, prolonged network partition were to occur, Cloud Spanner would prioritize consistency (CP) and potentially sacrifice availability in the affected region, thereby maintaining the integrity of data rather than letting all writes succeed in isolation.

What is Latency?

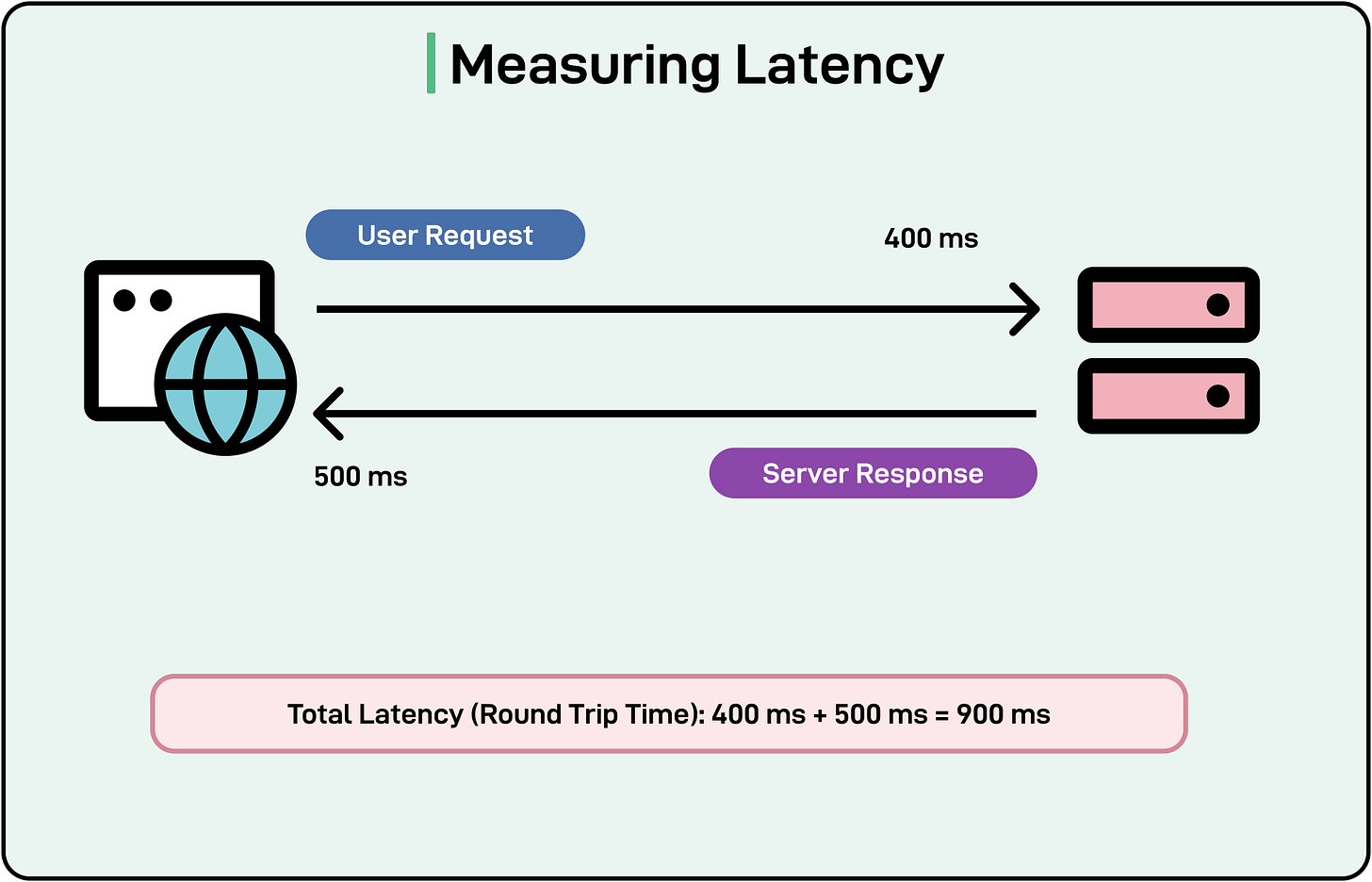

Latency in a distributed system refers to the delay between a client initiating a request and receiving a response.

This is distinct from throughput, which measures how many operations can be processed within a given time frame. Throughput can be high even if each operation takes a while (high latency), and conversely, a system might exhibit low latency but not handle many requests simultaneously.

The major sources of latency in a system are as follows:

Network Delays: When data travels across different regions or countries, it encounters physical constraints (speed of light) and a variety of network hops such as switches, routers, and potential congestion points. Even relatively short distances can accumulate noticeable delays when these hops add up.

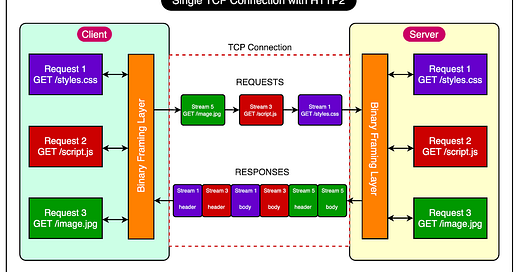

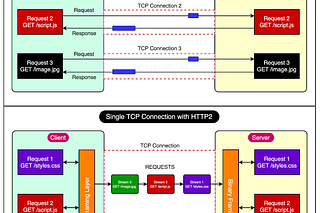

Protocol Overheads: Higher-level protocols (for example, HTTP/2, gRPC) and security layers like TLS can introduce additional round trips for handshakes and encryption. Consensus protocols (Paxos, Raft) used by distributed databases add more messages between nodes to agree on the order of operations, further increasing latency.

Application-Level Inefficiencies: Inefficient data serialization, large payloads, or poorly optimized database queries can all contribute to latency. When multiple microservices call each other sequentially, each service adds overhead, compounding the total response time.

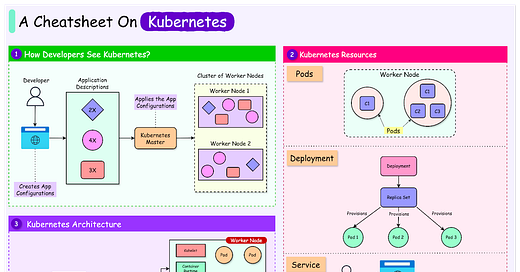

Resource Contention: Within each machine, CPU, memory, and disk I/O resources can be oversubscribed, causing delays in processing. For example, schedulers in container-orchestration environments like Kubernetes may place services on busy nodes, exacerbating wait times.

In a global application, cross-region calls might add hundreds of milliseconds of latency.

For example, a user in Europe calling an API endpoint in the US could see this delay worsen if the request also fans out to multiple internal services, especially those spanning different data centers. Large data transfers, such as sending MBs of JSON data across services, compound the issue by increasing serialization overhead and network travel time.

Simply looking at average (mean) latency can be misleading, as real-world traffic often has spikes that significantly affect user experience.

Therefore, developers commonly track p95, p99, or p999 latencies, meaning 95%, 99%, or 99.9% of requests complete below a certain threshold. For example, a service might have a median latency of 50 ms, but if 1% of requests exceed 500 ms, this could still frustrate a noticeable portion of users.

Understanding Partition Tolerance

A network partition occurs when one set of nodes in a distributed system becomes unable to communicate with another set.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that nodes have failed. Rather, it indicates the network links between them may be down, congested, or misconfigured. At large scales, where services often span multiple data centers or cloud regions, occasional network interruptions or degraded connectivity are unavoidable.

One major outcome of network partitions is the split-brain scenario. In this situation, each isolated set of nodes believes it has sole ownership of data or control responsibilities. Without careful safeguards, they could accept conflicting writes that lead to data corruption or inconsistencies once the partition is resolved.

Another potential issue is delayed or dropped messages that cause out-of-date data to propagate, triggering unpredictable behavior across dependent services.

This is why partition tolerance, the system’s ability to keep functioning (to some extent) even when nodes can’t fully intercommunicate, is considered non-negotiable in distributed system design.

To address the impact of partitions, different architectural approaches are followed:

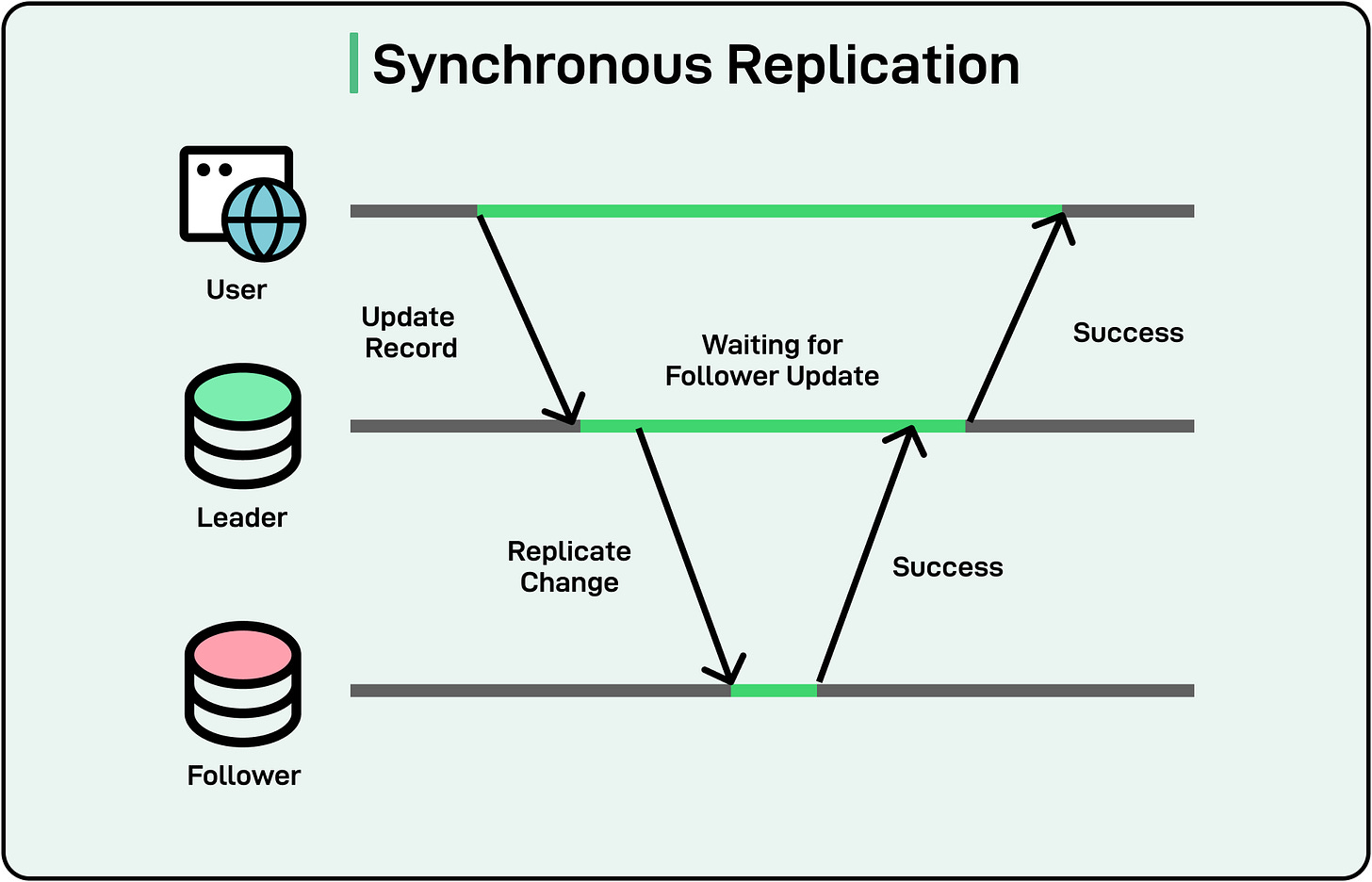

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Replication:

Synchronous replication requires all replicas to confirm a write before the system responds with success. While this ensures stronger consistency, it also means that if a network partition prevents a quorum of nodes from responding, writes may be blocked, reducing availability.

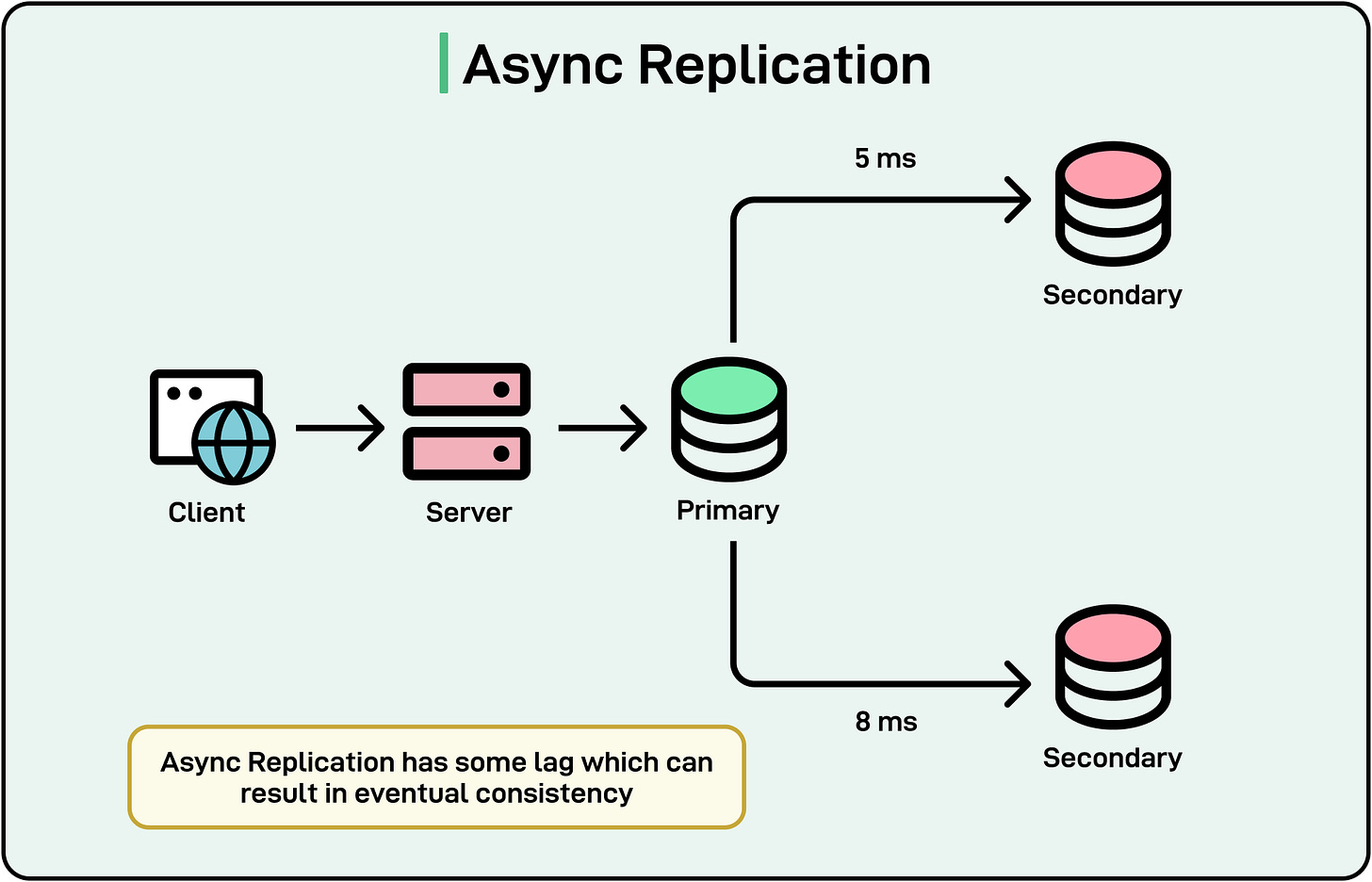

Asynchronous replication returns success once a primary node has acknowledged a write. Other replicas update eventually, which helps maintain availability during partitions but risks temporary data discrepancies.

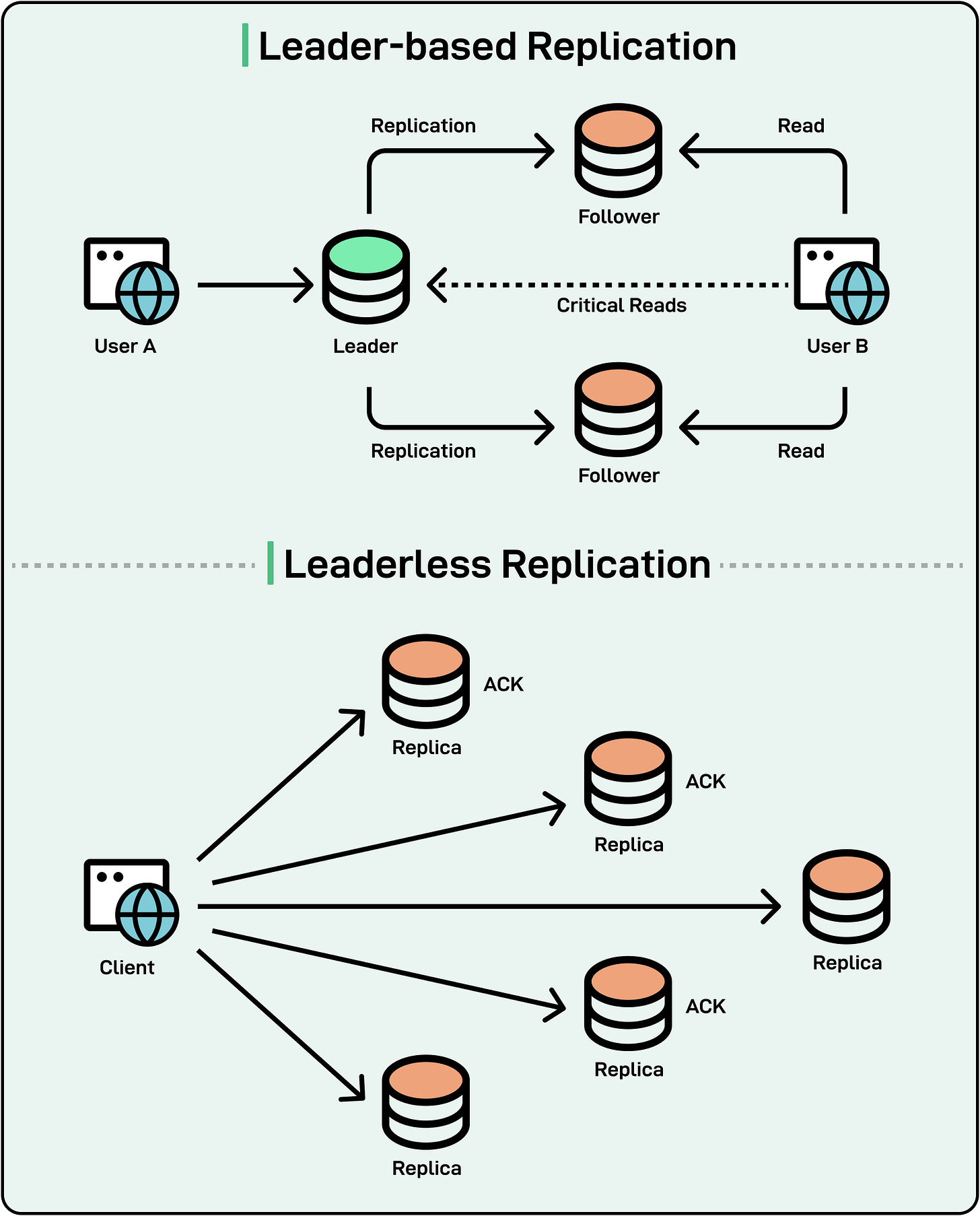

Leader/Follower vs Leaderless Replication:

Leader/Follower approaches designate a single leader node to coordinate writes. If the leader is cut off or fails, the system must elect a new leader, which can introduce downtime or risk split-brain if nodes aren’t careful. For example, Apache Kafka uses a leader/follower model for each topic partition, ensuring a single source of truth but requiring election protocols when leaders go offline.

Leaderless systems like Apache Cassandra distribute writes and reads among multiple replicas without a single primary coordinator. Clients can configure a “consistency level” that dictates how many replicas must respond before considering a request successful. During a partition, some replicas may become unreachable, but the cluster can still process requests at a lower consistency level, prioritizing availability.

See the diagram below that shows the difference between leader-follower and leaderless replication.

The Link Between Latency and Partition Tolerance

Latency and partition tolerance are deeply interconnected because both revolve around how distributed systems handle communication failures and delays.

Network partitions cause parts of a system to lose connectivity, even if temporarily. During this period, requests might keep retrying until they hit a timeout, or they could be routed to fallback nodes. In either case, responses slow down, so overall latency can increase. Even after the partition heals, the system may spend additional time on leader election, data synchronization, or conflict resolution. This recovery process can further inflate latency because nodes have to coordinate large batches of updates or verify data correctness before resuming normal operations.

For instance, in a leader-based system, once the leader becomes unreachable, the remaining nodes initiate an election. Until a new leader is elected, writes are blocked, which effectively translates into unbounded write latency for that duration. In some cases, reads may also be delayed if they are configured to fetch data from the leader only.

Availability vs Consistency Trade-Off

Many distributed architectures choose availability (AP) over consistency (CP) during partitions.

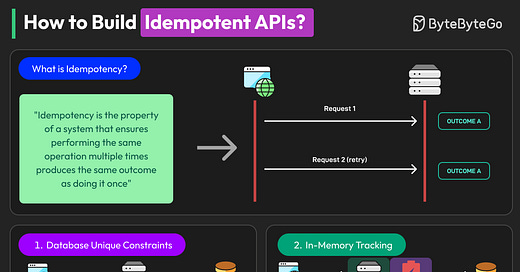

In an AP system, write requests might only reach a subset of nodes, which accept the update and return success. This keeps latency lower because the system responds promptly, but data consistency can temporarily suffer. Other nodes may not see the same state until the partition is resolved.

In contrast, a CP system will block some requests rather than serve stale or conflicting data. This approach protects data integrity but can increase latency (or lead to outright failures) when a partition prevents the required majority (quorum) from responding.

Consensus protocols like Paxos and Raft often rely on CP protocols.

They require a majority of nodes to agree before committing a write operation. Under partition, if the quorum is split and a leader cannot form a majority, the system halts writes. This design ensures consistent ordering of operations but can degrade availability and cause high latencies for updates, especially in large or geographically dispersed clusters.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Replication

Some systems mitigate the negative impact on latency by using asynchronous replication.

A primary node confirms a write immediately and then propagates changes to replicas in the background. This boosts availability and lowers write latency as seen by the client. However, it also opens a window where replicas are out of sync, meaning a read might return outdated data.

On the other hand, synchronous replication requires replicas to confirm writes, ensuring immediate consistency but potentially adding latency, especially if network links are slow or unreliable.

Ultimately, choosing a replication strategy depends on the business’s tolerance for stale reads, downtime, and potential data conflicts.

By recognizing how network partitions inflate latency—and by carefully choosing consistency, replication, and consensus models—engineers can design systems that strike a suitable balance between responsiveness and correctness.

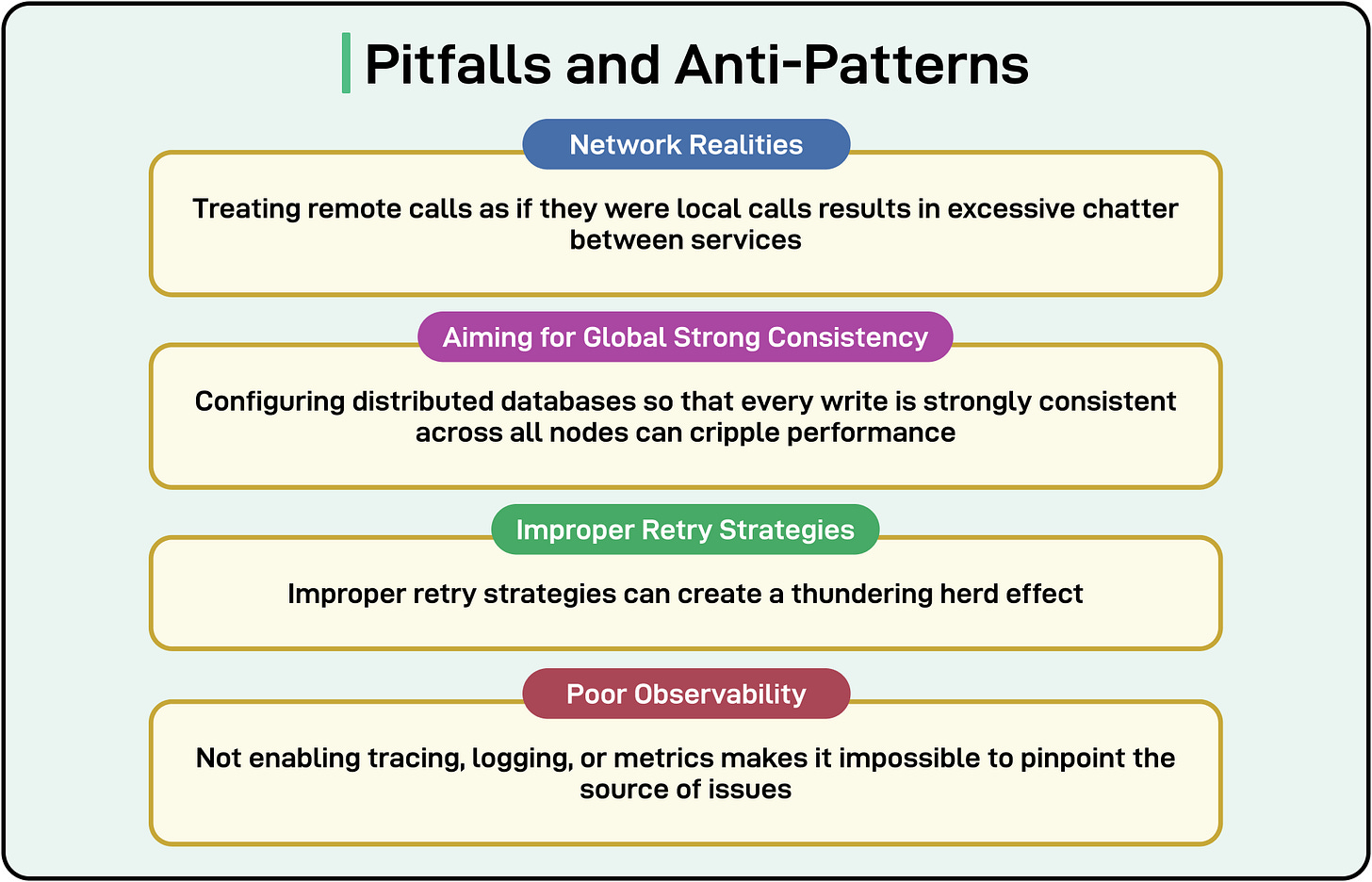

Common Pitfalls and Anti-Patterns

Distributed systems can unlock scalability and resilience, but they also bring complexities that aren’t always obvious to teams accustomed to single-node environments.

Below are some common pitfalls and anti-patterns that can trouble even seasoned developers:

Ignoring Network Realities: Treating remote calls as if they were local, assuming near-zero latency and unlimited bandwidth. This often manifests as excessive chatter between microservices or large synchronous payloads that drag performance.

Insisting on Global Strong Consistency for All Operations: Configuring distributed databases or services so every write must be fully synchronous and consistent across all nodes, regardless of use case. This can cripple performance under high concurrency or introduce latency when nodes are geographically dispersed.

Improper Retry Strategies: When services retry failed requests immediately during load or network glitches, they can create a “thundering herd” effect, piling on additional traffic and compounding latency.

Poor Observability: Not enabling services for tracing, logging, or metrics, making it nearly impossible to pinpoint the source of slowdowns or data inconsistencies in a multi-service environment.

Best Practices for Latency and Partition Tolerance

Let us now look at some best practices for dealing with latency and partition tolerance in distributed systems:

Use Resiliency Patterns: First and foremost, integrate circuit breakers into the communication paths. When a service is unresponsive or struggling, circuit breakers help prevent a flood of requests from compounding failures and escalating latency. In tandem, bulkhead patterns isolate system components so that a surge or failure in one service doesn’t drag down everything else.

Leverage Asynchronous Communication: Where possible, use asynchronous messaging (for example, message queues, and event-driven designs) instead of synchronous calls. This approach reduces blocking, lets downstream services process requests at their own pace, and limits the cascading effect of network delays. It’s also more robust against partitions. If a node goes offline, queued messages remain until the node is online again.

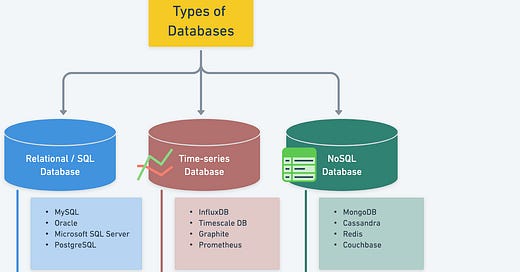

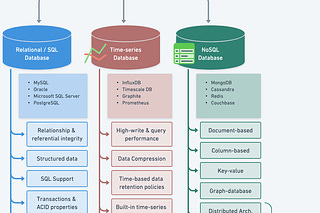

Choose Appropriate Consistency Model: Not all data needs strong consistency. For high-traffic, globally distributed workloads, eventual consistency can improve performance and reduce latency. On the flip side, strong consistency is critical for operations like financial transactions or mission-critical state updates. Make these choices consciously. For example, tunable consistency settings in NoSQL databases (like Cassandra’s) help adjust trade-offs to match the business requirements.

Design for Partitions: Assume that partitions will happen. Build the system to degrade gracefully: implement fallback paths, read-only modes, or partial operations when services become unreachable. This ensures users can still accomplish essential tasks rather than facing a complete service shutdown.

Invest in Monitoring: Track high-percentile latencies (p95, p99, p999) rather than just average times. Implement distributed tracing (using tools like Jaeger and Zipkin) and structured logging to quickly isolate bottlenecks. Real-time dashboards and alerts can help detect emerging issues before they become severe outages.

Summary

In this article, we have looked at the importance of latency and partition tolerance in the context of distributed systems.

Let’s summarize the key learning points in brief:

Distributed systems spread workloads across multiple nodes, offering scalability and fault tolerance.

However, more nodes mean more complexity. Developers must manage issues like latency and partial failures.

The CAP Theorem states that developers need to choose between properties like consistency, availability, and partition tolerance.

Latency is the delay from request initiation to response, and it is different from throughput. Major sources of latency are network hops, protocol overhead, application-level inefficiencies, and resource contention.

Large-scale networks will experience node isolation or link failures. If systems aren't designed for partitions, this can lead to split-brain scenarios and data inconsistencies.

Waiting on unreachable nodes or network retries can dramatically increase response times.

AP systems accept writes during partitions but risk conflicts. CP systems block writes to ensure consistency.

Protocols like Paxos or Raft emphasize strong consistency but can raise latency or reduce availability under partition.

Common pitfalls and anti-patterns developers should avoid are ignoring network realities, aiming for a strong global consistency for all operations, and improper retry strategies.

Best practices are related to choosing resiliency patterns, using asynchronous communication, and choosing the right consistency model.

References:

Temporal.io solves this