APIs are the front doors to most systems.

They expose functionality, enable integrations, and define how teams, services, and users interact. But while it’s easy to get an API working, it’s much harder to design one that survives change, handles failure gracefully, and remains a joy to work with six months later.

Poorly designed APIs don’t just annoy consumers. They slow teams down, leak data, cause outages, and break integrations. One inconsistent response structure can turn into dozens of custom client parsers. One missing idempotency check can result in duplicate charges. One weak authorization path can cause a security breach.

Well-designed APIs, on the other hand, create leverage and help the team do more. Some defining features are as follows:

They act as contracts, not just access points.

They scale with usage.

They reduce surprises for the developers and other stakeholders.

And they are reliable, internally and externally.

Most of the pain in API systems doesn’t come from the initial development. It comes from evolving them: adding new fields without breaking old clients, handling retries without state duplication, and syncing data between systems without losing events.

A good API design is defensive and anticipates growth, chances of misuse, and failures. It understands that integration points are long-lived and every decision has an impact down the line.

In this article, we explore the core principles and techniques of good API Design that make APIs dependable, usable, and secure. While our focus will primarily be on REST APIs, we will also explore some concepts related to gRPC APIs to have a slightly more holistic view.

Principles of Good API Design

When an API becomes clever, returning different response shapes, mutating state on a GET, or encoding meaning through inconsistent naming, it turns from a contract into a puzzle.

A well-designed API should not be a puzzle. They should behave predictably, use consistent structures, and make few assumptions about clients.

Therefore, good API design prioritizes clarity above all else. It anticipates scale, change, and human error. The most reliable systems often stem from the most unremarkable APIs because those APIs gave clients no sudden surprises.

Let’s look at a few principles of good API Design.

Consistency Reduces Friction

Uniformity across endpoints simplifies development. When resource naming follows clear conventions and response formats adhere to a shared structure, teams can reuse client code and debugging tools.

Inconsistent APIs, on the other hand, introduce silent traps. For example, consider an API that returns dates as ISO strings in some endpoints and Unix timestamps in others. Or one where error responses sometimes use error codes and other times return raw strings. Each exception forces a workaround, and those workarounds accumulate into brittle integrations.

Nouns Represent Resources, Not Actions

REST works best when endpoints map to domain concepts (orders, users, or payments) rather than commands.

For example, the endpoint “POST /users” conveys intent more clearly than POST /createUser, which blends transport semantics with business logic.

Resource-oriented URLs also support logical nesting (/users/123/orders) and permission modeling. Overusing verbs in paths leads to RPC-style design, where endpoints behave more like remote procedures. This breaks standard tooling, limits caching options, and makes the API harder to evolve.

Method Semantics Guide Expectations

HTTP methods carry distinct semantics that shape how clients, proxies, and infrastructure behave:

GET retrieves resources without side effects. It is safe and cacheable.

POST creates new resources. It is not idempotent by default.

PUT replaces resources and guarantees idempotency.

PATCH applies partial updates.

DELETE removes resources and expects idempotency.

Violating these conventions often leads to indirect failures. A GET that triggers writes breaks caching. A retry on POST without safeguards creates duplicate records. APIs that align with method semantics integrate more reliably with tooling and infrastructure.

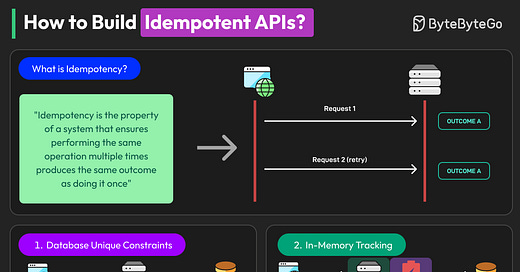

Idempotency Protects Against Retries

Clients retry requests when connections drop or timeouts occur. Without safeguards, those retries can create duplicate orders, inconsistent states, or unintended charges.

Idempotency solves this. Systems use idempotency keys (typically passed in headers) to detect repeated requests and return the original result. This pattern works especially well for operations tied to money, provisioning, or resource creation.

Skipping idempotency during API design leads to state drift and operational pain during outages.

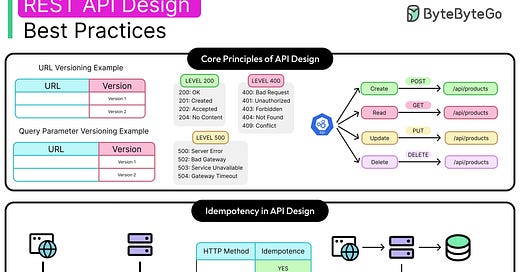

Versioning for Sustainable Change

Every API evolves. Fields change, validation rules tighten, and new features arrive. Without versioning, even small shifts risk breaking clients.

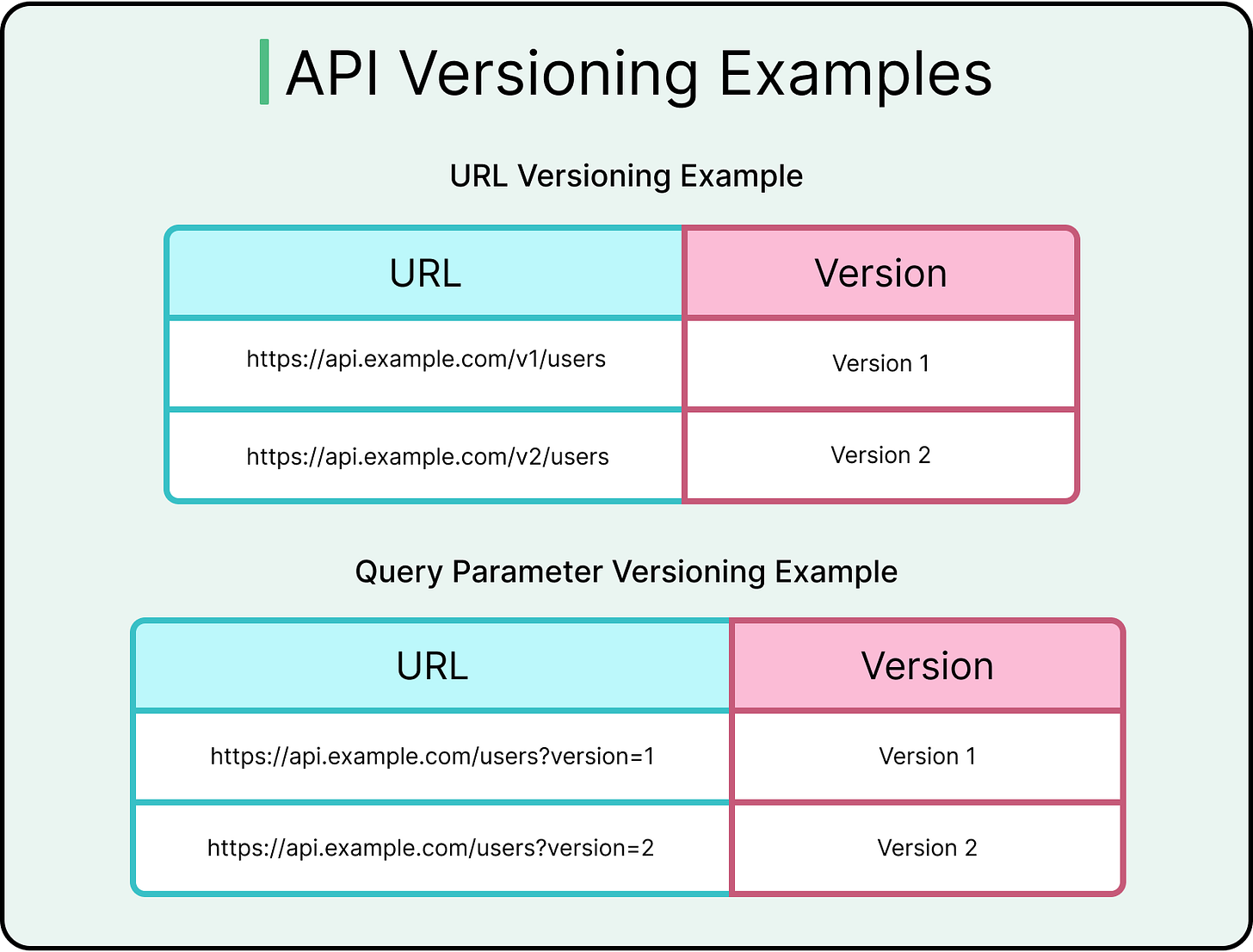

URI versioning (/v1/users) offers the clearest and most discoverable path. Alternatives like query parameter-based, header-based, or media-type versioning provide cleaner URLs but increase tooling complexity and debugging costs.

Whichever strategy is used, versioning works best when applied early and managed intentionally. Versioning doesn’t allow teams to make careless changes, but it enables controlled evolution.

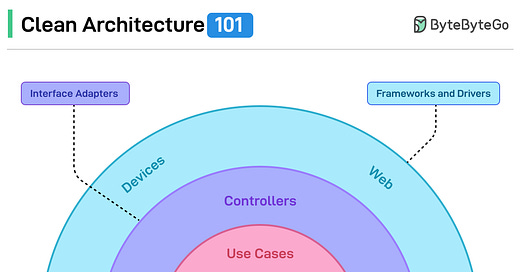

Protocol Choice (REST versus gRPC)

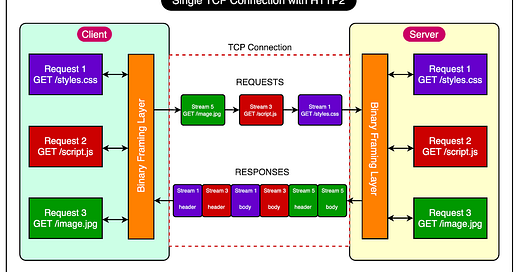

The choice of protocol matters while building APIs. Often, the choice comes between REST and gRPC.

REST provides human-readable interfaces, broad compatibility, and tooling support. It suits public APIs, mobile clients, and browser integrations.

gRPC offers better performance, schema enforcement, and bi-directional streaming. Built on HTTP/2 and Protobuf, it fits internal service communication where latency and structure matter more than accessibility.

Some systems adopt both: REST externally and gRPC internally. This hybrid approach allows each protocol to do what it does best.

Predictable Responses Simplify Integration

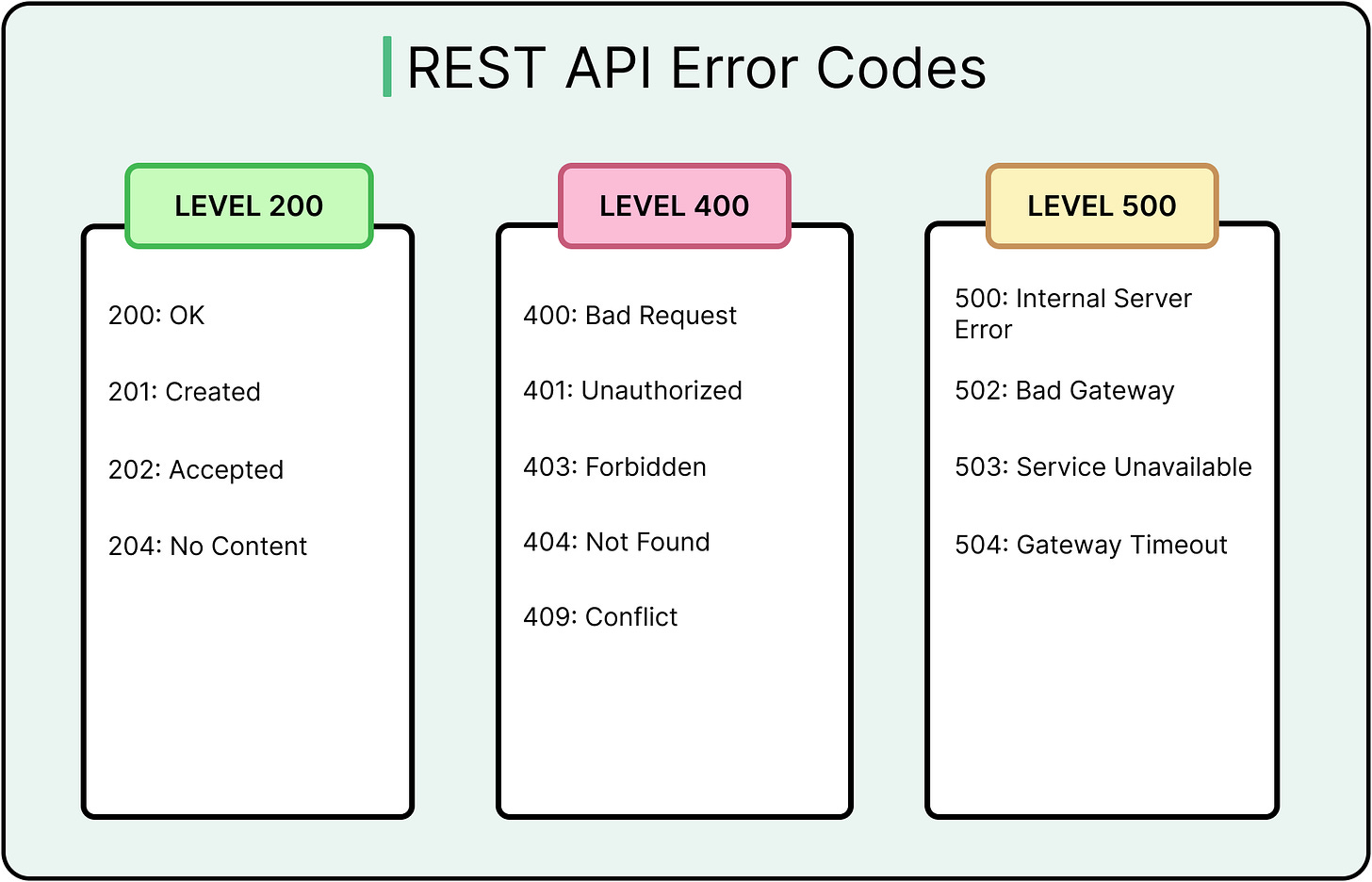

Clients benefit from uniform response structures. A consistent format that involves wrapping successful results in a data object and failures in an error block allows shared parsers, better observability, and more stable error handling. Using the appropriate error codes is also important.

The diagram below shows the common REST API Error Codes.

Without consistency, client logic branches across endpoints. Some responses return plain values, others embed metadata, and a few use nested fields for no clear reason. Over time, this inconsistency spreads across logging, testing, and monitoring layers.

Standardized response shapes act as a contract, making things far more convenient.

Schema-First Design Prevents Drift

Schema-first design reduces ambiguity. Using OpenAPI (for REST) or Protobuf (for gRPC) enforces the structure, supports contract validation, and enables code generation. Schemas also serve as documentation, a source of truth, and a gatekeeper for change.

Teams that start with schemas catch problems earlier. It has a few important advantages:

Contract diffs reveal breaking changes.

Consumers align more easily.

Automated tests validate assumptions before runtime.

APIs without schemas tend to drift. Fields change silently, and documents lag behind the actual behavior. This results in breaking integrations.

Understanding Idempotency

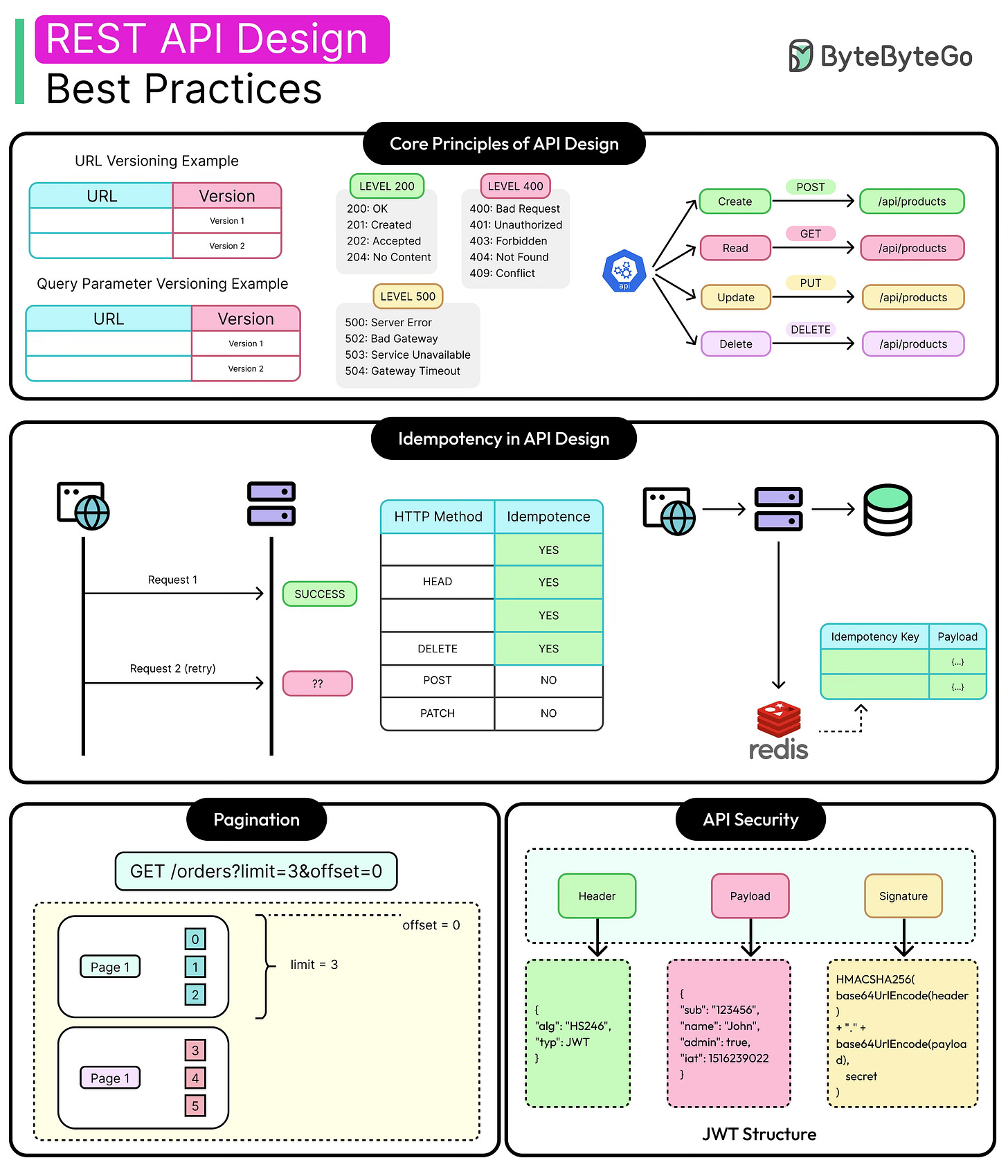

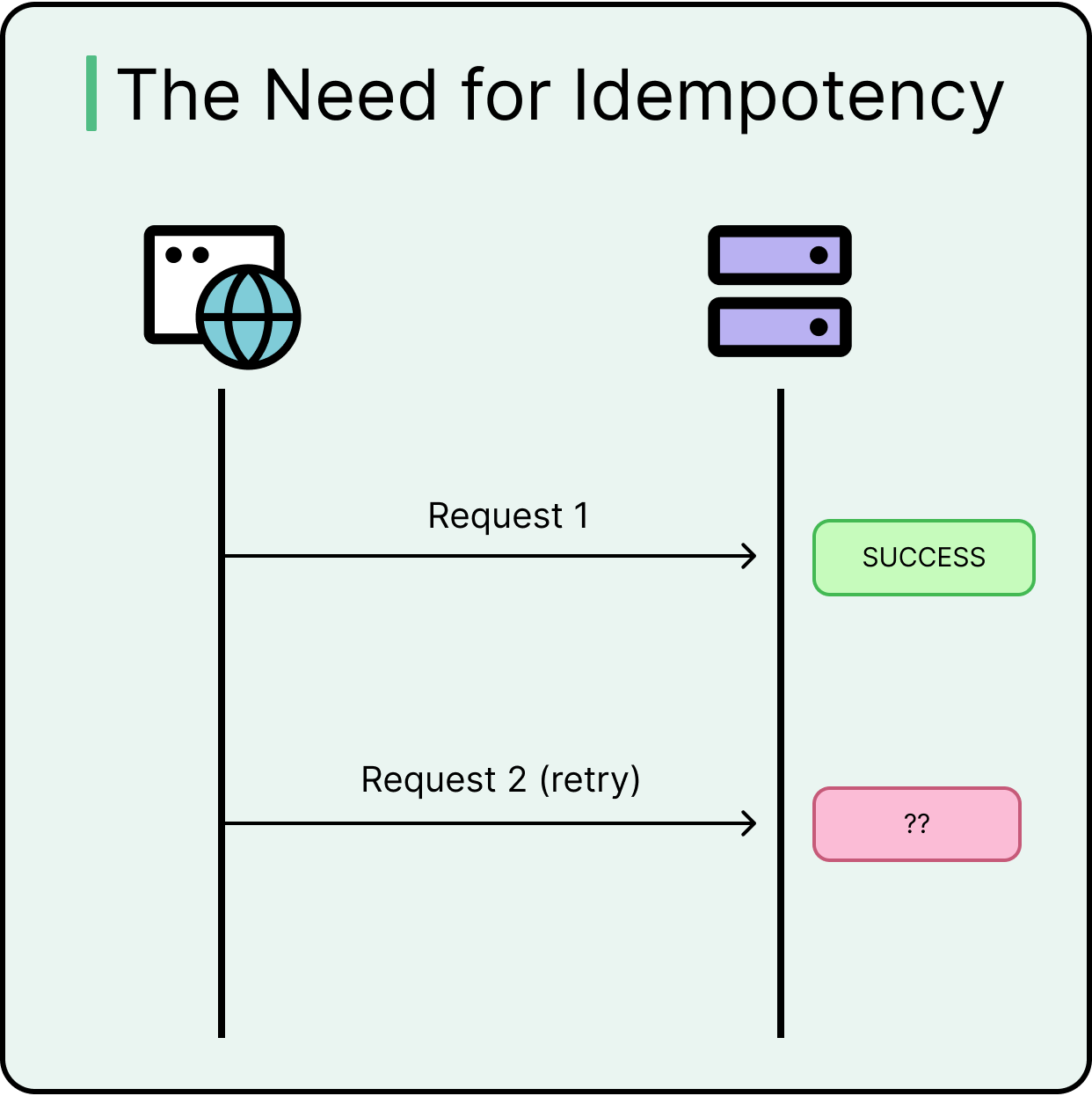

Let’s understand what happens when API design doesn’t accommodate idempotency.

At some point, a client times out mid-request (such as when placing an order or making a payment). The user clicks “Confirm” again, and a retry is triggered automatically. The system receives the same request twice. Without idempotency safeguards, it processes both, resulting in scenarios like duplicate orders, double payments, and conflicting states.

This scenario isn’t rare. It’s quite normal in distributed systems. The only way to make retry logic safe is to make the server operations idempotent.

What Makes an Operation Idempotent?

An operation is idempotent when multiple identical calls produce the same result as one call. This doesn’t mean the server does nothing on a retry. It means the outcome doesn’t change after the first successful execution.

For example:

Deleting the same resource twice with DELETE /users/123 results in success both times.

Sending the same payment request twice should either process once or return the result of the original attempt, not charge twice.

Idempotency protects critical operations from being replayed unintentionally.

Method Semantics: Where Idempotency is Expected

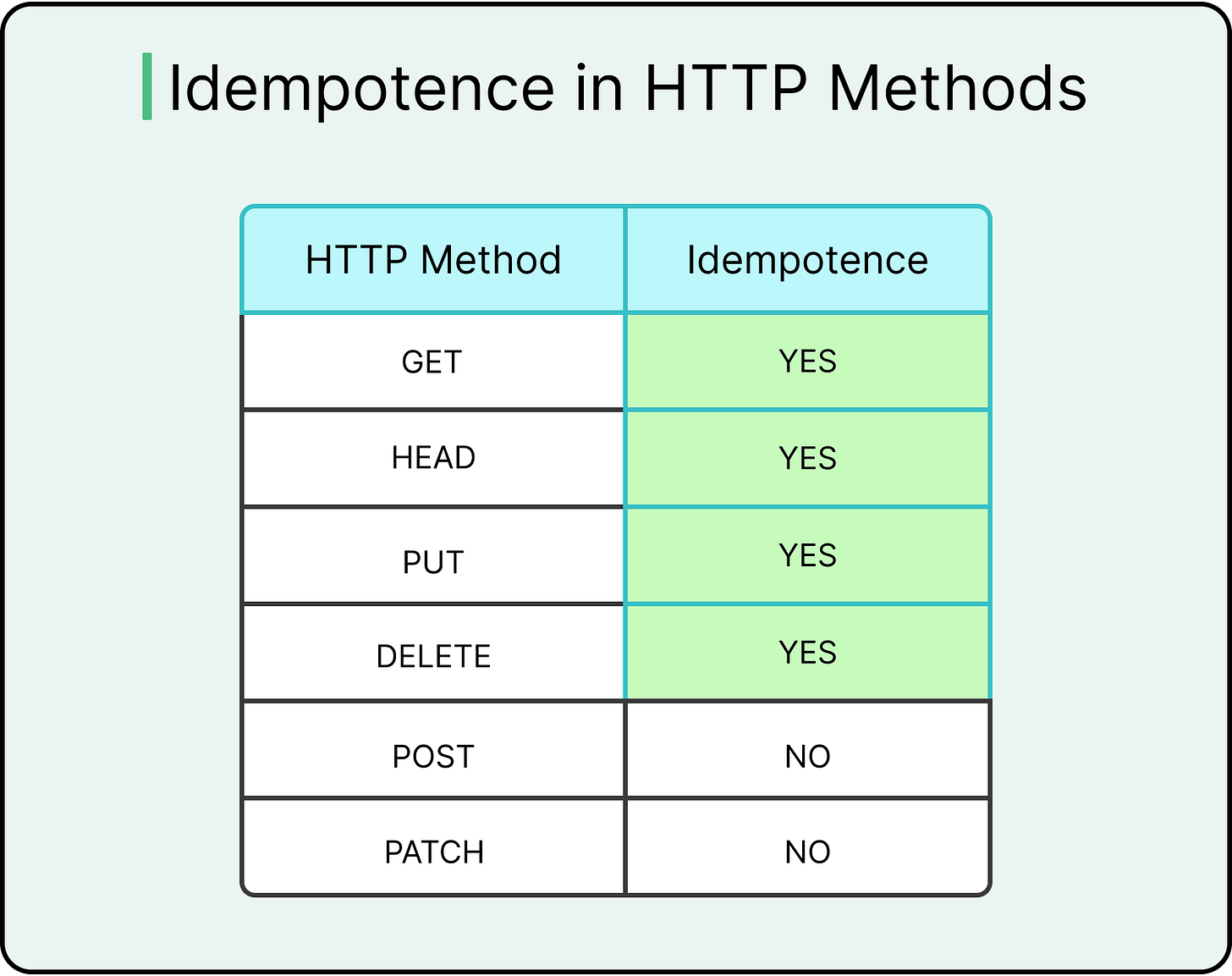

HTTP defines which methods should be idempotent:

GET and HEAD are safe and idempotent by nature. They retrieve metadata without modifying the state.

PUT and DELETE are defined as idempotent. Calling them multiple times results in the same resource state.

POST is not idempotent by default, but that’s exactly where most systems need extra care. Also, PATCH is not generally considered idempotent.

Critical POST endpoints, like those that trigger payments, account creations, or provisioning, must enforce idempotency explicitly.

When to Enforce Idempotency?

Idempotency adds complexity. It’s generally unnecessary for endpoints that don’t trigger significant side effects or financial transactions.

But in the following cases, skipping it can become a liability:

Financial operations (for example, payment processing, refund issuance)

Provisioning (for example, VM creation, account registration)

Webhook receivers (where retries are often automatic)

Critical workflows (like order submission or subscription setup)

Without idempotency in these flows, retries become a source of risk rather than resilience.

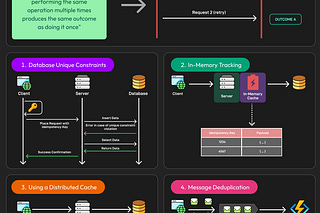

Idempotency Implementation

Most systems enforce idempotency by requiring clients to include an idempotency key: a unique string that identifies the logical operation, not the HTTP request.

Some common characteristics across various implementations are as follows:

Sent as a header (for example, Idempotency-Key: abc123).

Scoped to a resource or endpoint.

Stored server-side, often with a TTL.

Return the original result if the same key is received again.

This pattern allows safe retries without repeating the underlying operation. Stripe and other payment APIs popularised this approach, especially in POST requests.

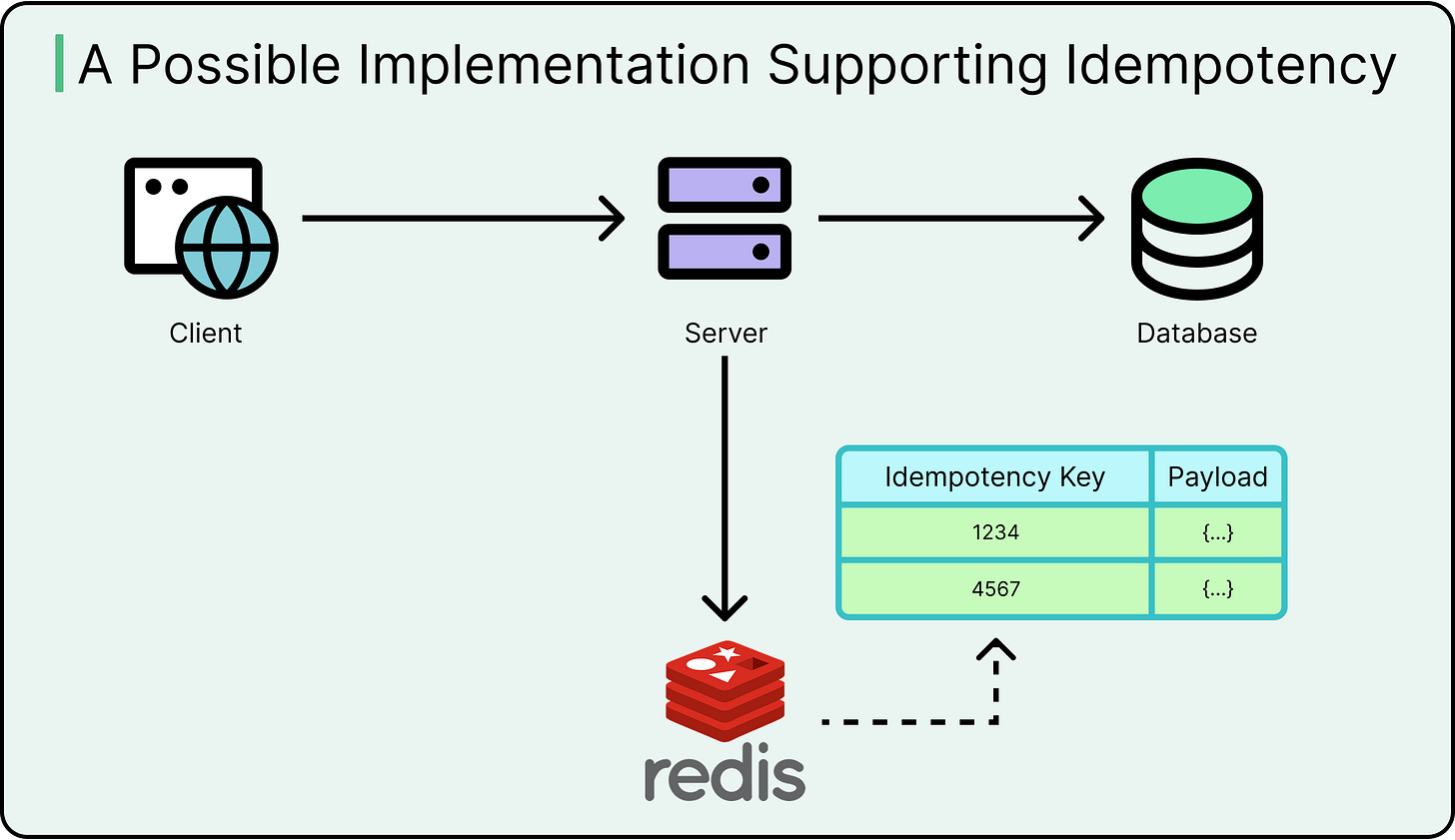

A typical implementation pattern works as follows:

The client sends a POST request with a unique idempotency key.

The server checks storage (cache, DB, Redis) for an existing result tied to that key.

If found, it returns the original response, skipping execution.

If not found, the server performs the operation, stores the result keyed by the idempotency token, and returns the response.

Optionally, the key expires after a timeout window.

See the diagram below for a possible implementation to support idempotency:

This flow ensures exactly-once effects, even if the request is received multiple times.

Storing idempotency tokens isn’t trivial at scale. Some design decisions include:

Where to store the token: Redis offers low latency, whereas relational DBs offer durability.

How long to keep it: Long enough to cover retries and short enough to avoid a bloated state.

What to store: Store the complete response or a canonical representation of the request result.

Also, collisions must be handled carefully. If the same key arrives with a different payload, the server must reject it with a clear error to avoid ambiguity.

Trade-offs and Limitations

Some trade-offs and limitations that should be considered while implementing idempotency are as follows:

Enabling idempotency adds infrastructure overhead.

Token storage requires write coordination.

Stateless services must integrate temporary persistence.

Edge caches complicate validation, and badly implemented logic can return stale or incorrect data.

However, failing to implement idempotency where needed can lead to duplicate charges, resource over-provisioning, corrupted system state, and tense debugging sessions. In systems where retries are likely and side effects are expensive, the trade-off favors idempotency.

gRPC and Idempotency

One thing to note is that gRPC doesn’t provide built-in idempotency semantics like HTTP methods. Engineers must enforce idempotency by:

Embedding request IDs in the message.

Server-side deduplication logic.

Handling retries at the client layer with caution.

This puts more responsibility on application developers, especially in systems using retries or streaming.

Pagination Techniques

Most modern systems expose lists of things: orders, comments, users, and transactions. The expectation is simple: fetch a page, scroll, and load the next.

But under the hood, list endpoints face a difficult problem: how to paginate large or fast-changing datasets without breaking performance, consistency, or user experience.

Without pagination or with inefficient pagination, the list endpoints become dangerous. Large datasets can cause:

Performance bottlenecks: Full-table scans slow down systems.

Payload bloat: Transferring thousands of items strains networks and clients.

Unstable queries: As data changes between requests, results shift unpredictably.

In other words, a poor pagination approach leads to missing data, duplicate records, degraded performance, or failed syncs. Pagination limits the scope of a request. It makes results manageable, consistent (within reason), and friendly to systems under load.

Reliable pagination starts with choosing the right strategy for the workload. Here are a few we can choose from:

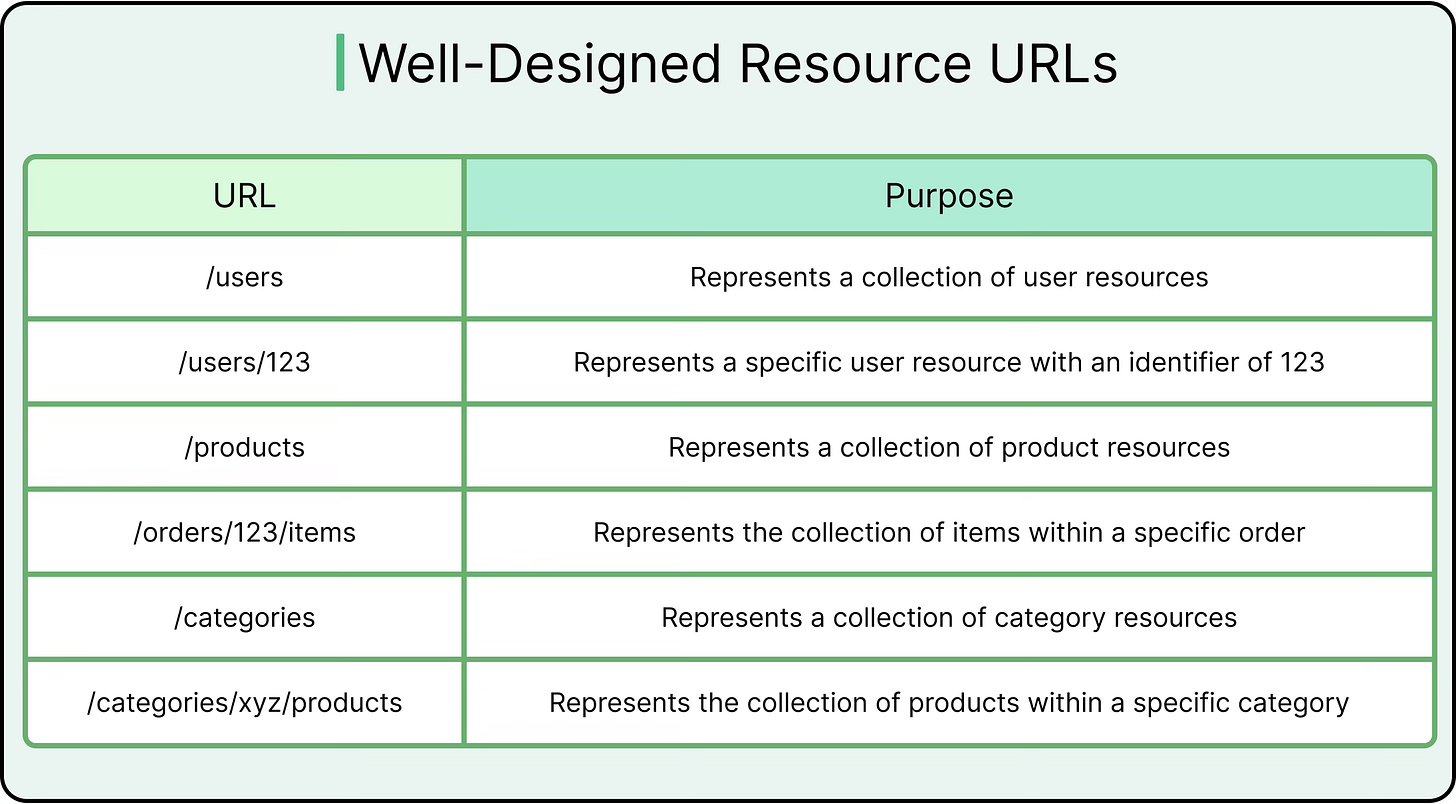

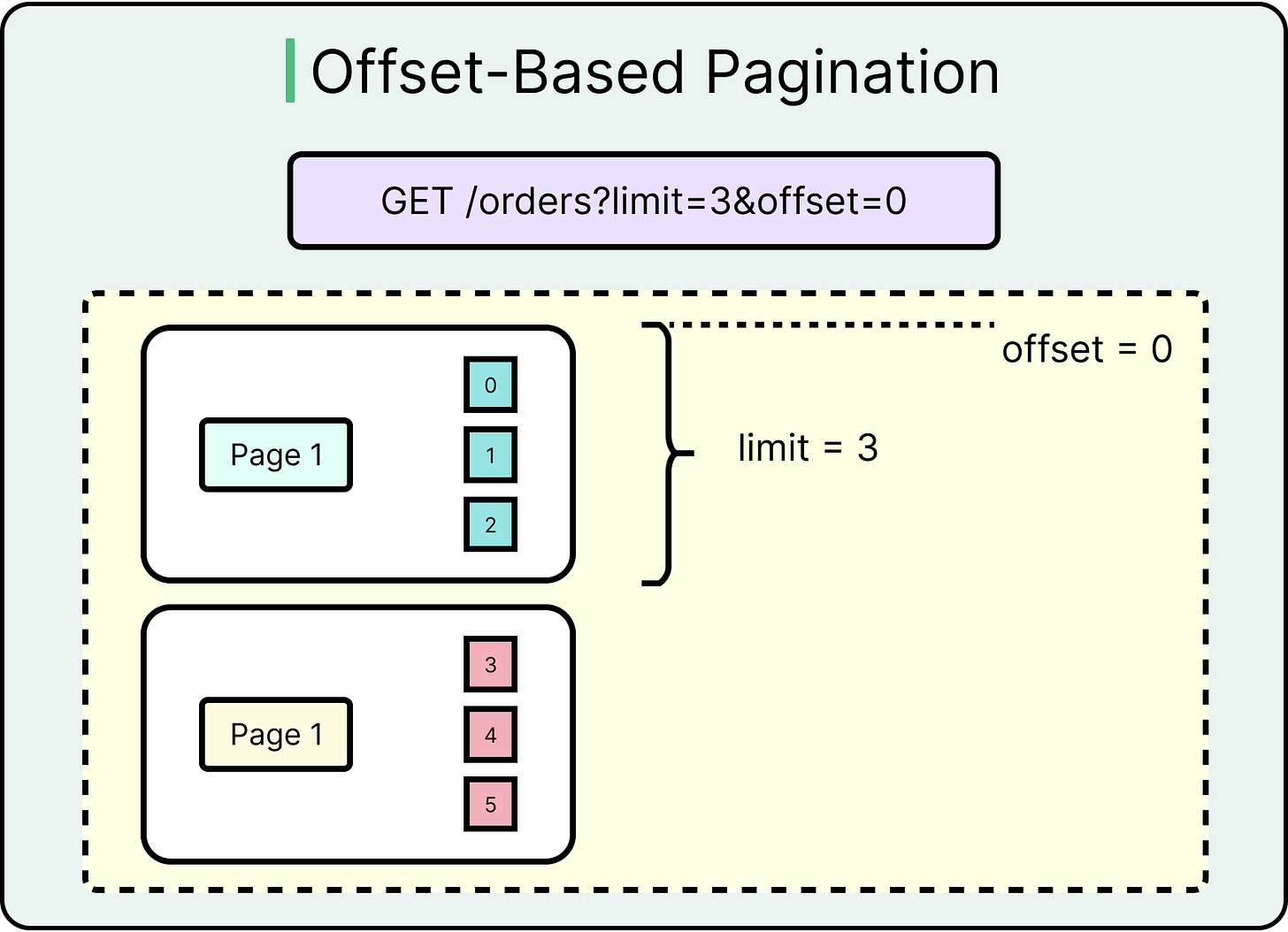

Offset-Based Pagination

Offset-based pagination uses query parameters like ?limit=20&offset=40. It works by skipping a certain number of rows and returning the next batch.

It works well because it is easy to implement with SQL using the LIMIT and OFFSET keywords. It also makes things predictable for UI scroll and paging controls.

See the diagram below:

However, offset-based pagination breaks down when dealing with fast-changing data. Inserts or deletes between pages cause record shifts or duplicates. High offset values result in full table scans, harming performance.

To summarize, offset pagination is fine for dashboards, admin panels, and stable lists. It falls apart in real-time feeds or distributed sync systems.

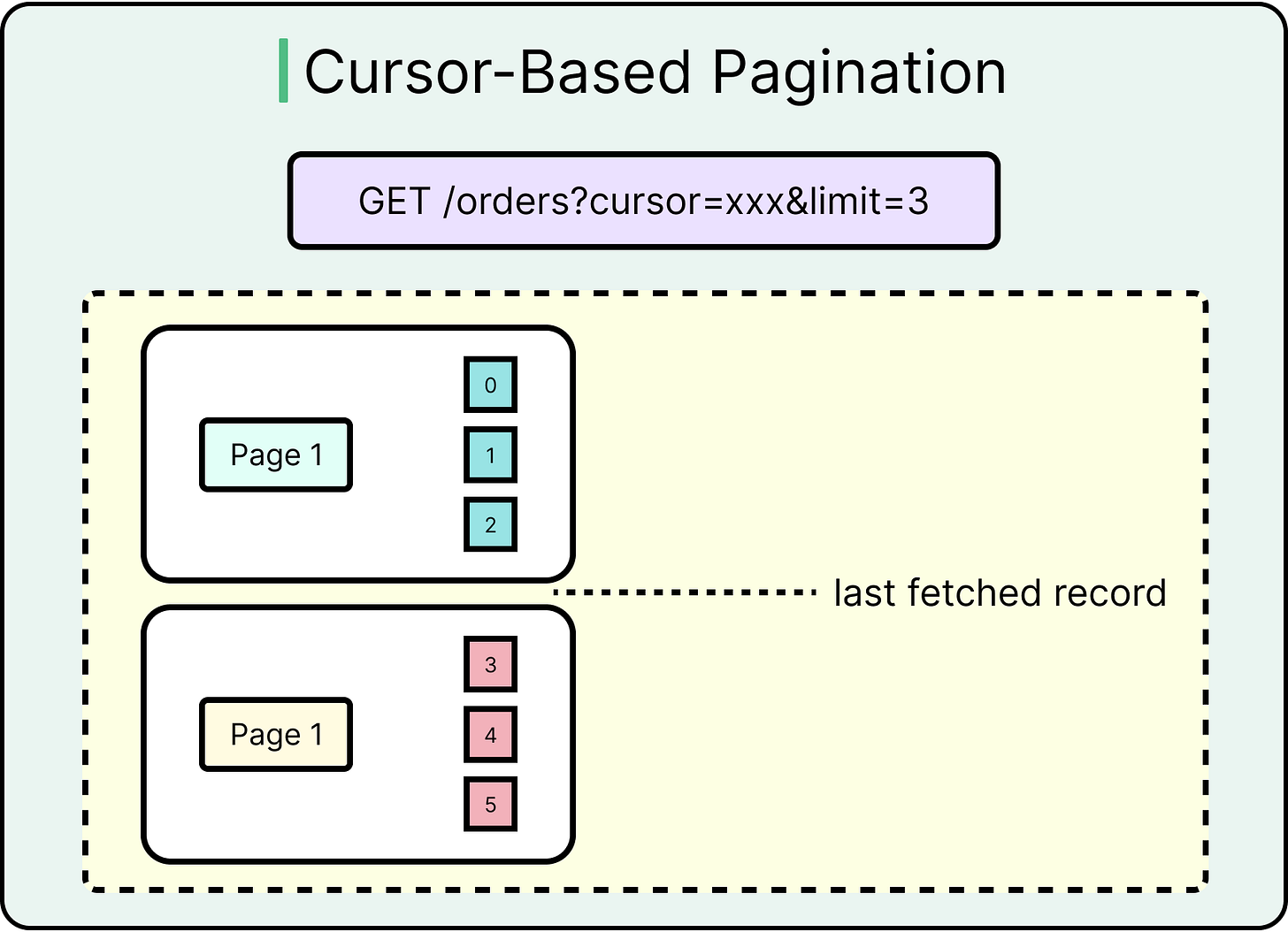

Cursor-Based Pagination

Cursor-based pagination avoids offsets entirely. Instead, it uses a cursor, usually a unique field like created_at or id, to fetch the next page relative to the last record received. For example, see the parameter ?limit=20&after=1679212341, where the cursor is a timestamp or ID.

This approach is more stable under inserts or deletes and avoids expensive offset scans. Cursor-based pagination is easy to resume from the last seen time and plays well with time-ordered data.

See the diagram below:

The main challenge is that this approach requires unique, ordered fields (such as auto-incremented or timestamp-based). Clients must store the last cursor to paginate reliably.

This approach is ideal for activity feeds, mobile apps, and event logs.

Keyset Pagination

Keyset pagination is a refined form of cursor pagination that uses indexed fields to create efficient WHERE clauses. For example:

SELECT * FROM posts

WHERE created_at < '2023-03-24T15:00:00Z'

ORDER BY created_at DESC

LIMIT 20;It performs well on large datasets and avoids skipping rows. For feeds and APIs optimized for scrolling, this is a worthwhile trade.

Design Choices for Pagination

Regardless of strategy, paginated APIs work better with consistent metadata. Good pagination responses often include:

items: The current page of results

has_next: A boolean indicator of more data

next_cursor or next_token: Continuation pointer

total_count: Optional, useful for UI, but expensive to compute on large datasets

Some systems avoid total_count entirely due to performance concerns. Others compute it asynchronously and return approximate values.

Pagination in gRPC

gRPC is different in the way that it doesn't support query parameters like REST. Instead, pagination is modeled via request and response messages:

message ListRequest {

int32 limit = 1;

string page_token = 2;

}

message ListResponse {

repeated Item items = 1;

string next_page_token = 2;

}This structure maps cleanly to token-based pagination. Clients store the token from the last response and pass it on in the next request. Since gRPC supports streaming, pagination can also be avoided entirely when full datasets are streamed incrementally.

API Security Considerations

An API operates in an adversarial environment and is often the most exposed surface in a system. They deal in raw access to data, logic, and permissions. When misconfigured, they can hand over more than intended to attackers, bots, or careless clients.

Security failures rarely look dramatic at first. They often appear quietly, such as a forgotten debug endpoint without auth, a public S3 bucket serving private files, a token that never expires, and so on.

These flaws rarely show up in staging and often surface in production. Ultimately, these issues compound and eventually result in a breach.

Strong API security starts with the mindset that anything exposed will be probed by automation, curiosity, or intent. It isn’t optional, but a foundational aspect of API Design.

Authentication vs Authorization

Security failures often start with the boundary between authentication and authorization. Here’s what the two terms mean:

Authentication answers: Is this caller who they claim to be?

Authorization answers: Can this caller access this specific resource, in this specific way?

Systems that authenticate correctly but authorize loosely often expose internal APIs, leak unrelated user data, or permit the elevation of privilege.

Token validation alone isn’t enough. A valid token doesn't mean the request is safe. It only proves the caller’s identity, not that the action is allowed. Mistakes here often involve:

Reusing admin tokens across systems.

Skipping resource-level checks.

Over-scoping tokens (for example, “read-write-admin” instead of “read:user:123”).

Each request must be scoped to what the caller is explicitly allowed to do.

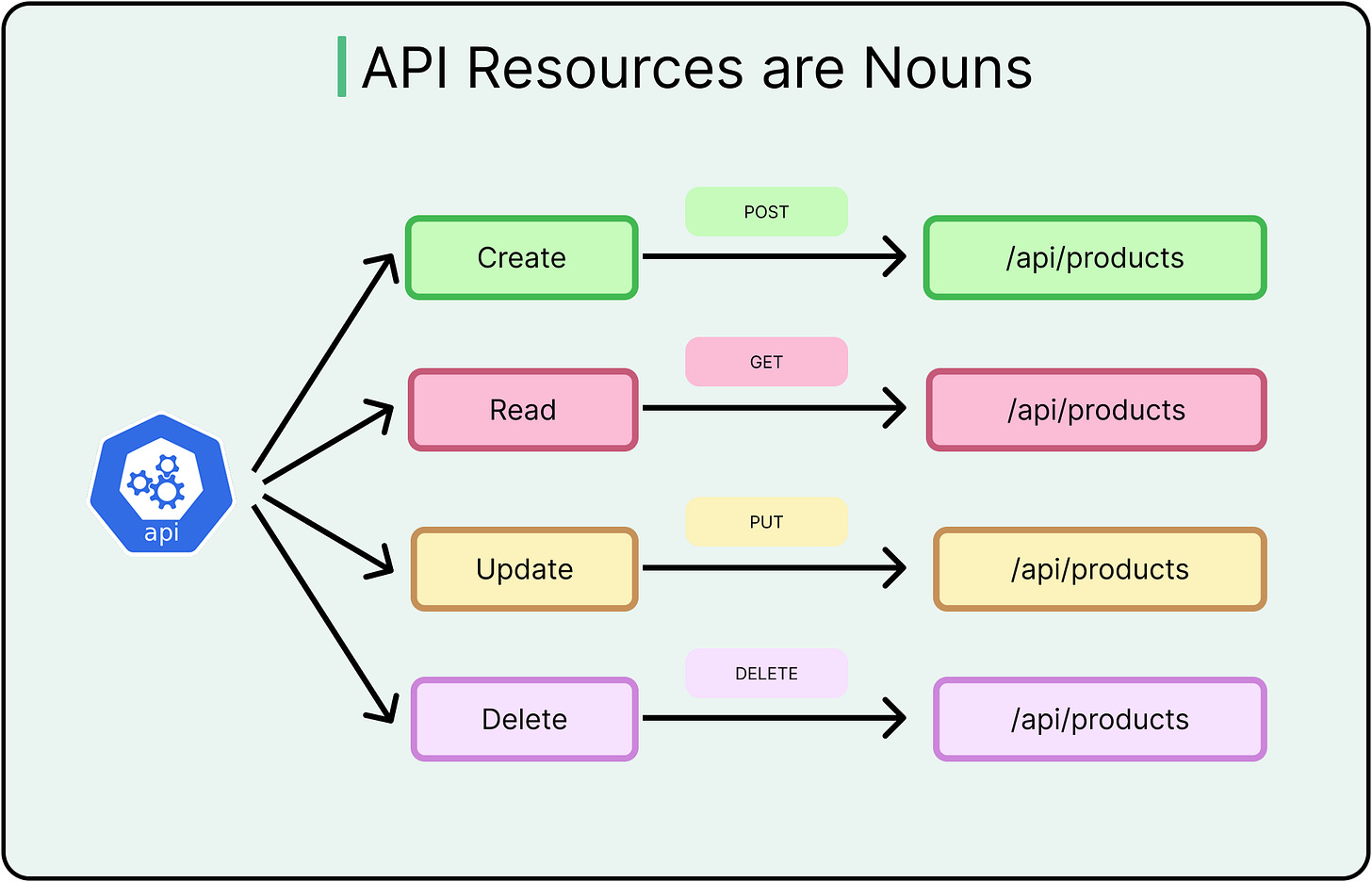

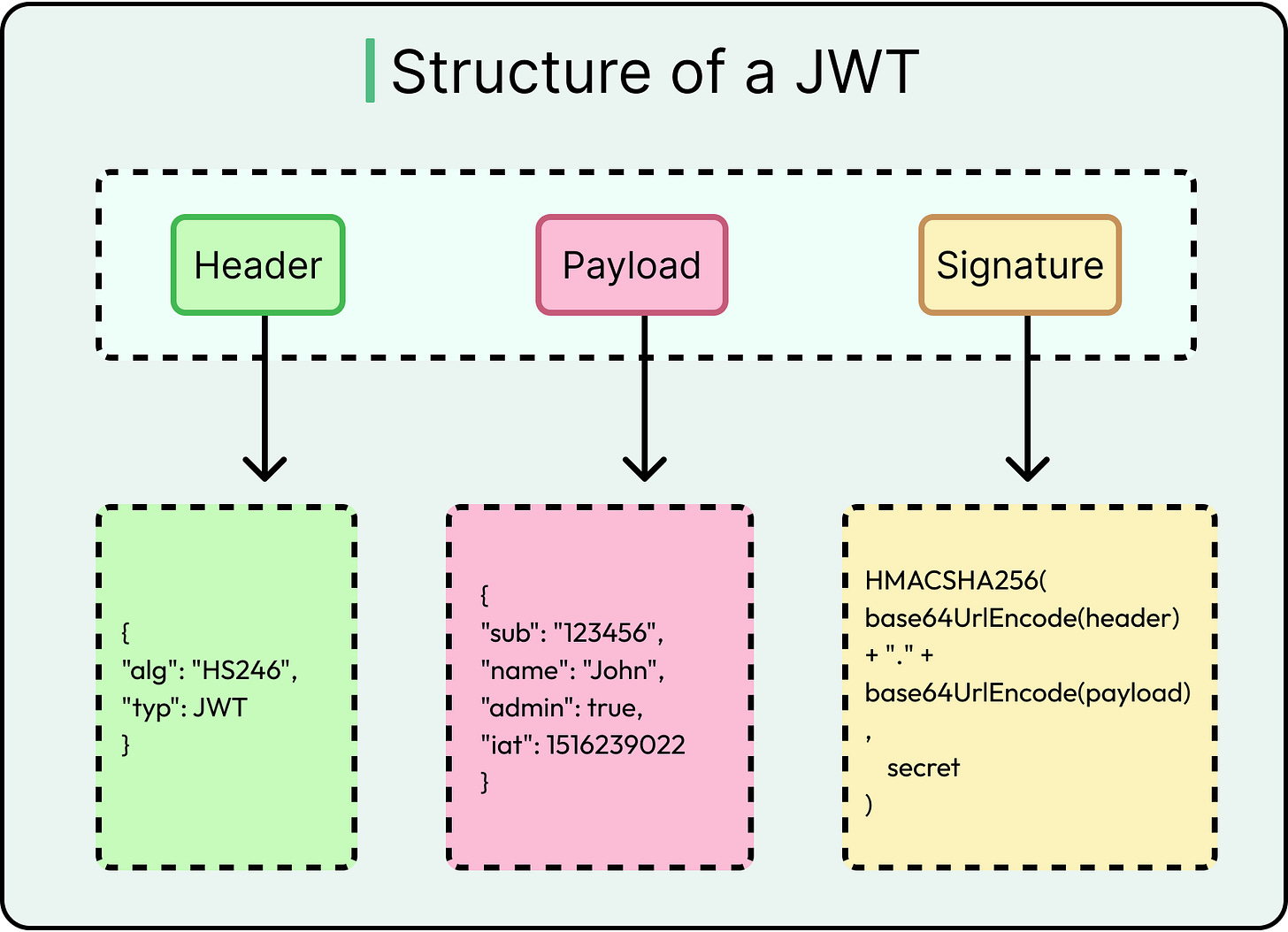

Token Types: JWT, OAuth2, and API Keys

APIs rely on a few standard methods to authenticate requests:

API Keys: Simple shared secrets. Easy to implement but hard to scope or revoke. Suitable for internal systems or read-only integrations.

JWTs (JSON Web Tokens): Self-contained credentials with claims. Efficient and stateless, but prone to misuse if validation isn’t strict.

OAuth2: A delegation protocol that lets users or services authorize limited access. Common in third-party integrations and public APIs.

See the diagram below that shows the structure of a JWT.

Each method carries trade-offs in revocability, scope, storage, and complexity.

JWTs shine in performance but expire poorly. OAuth offers granularity but increases implementation overhead. API keys are convenient, but often over-grant access.

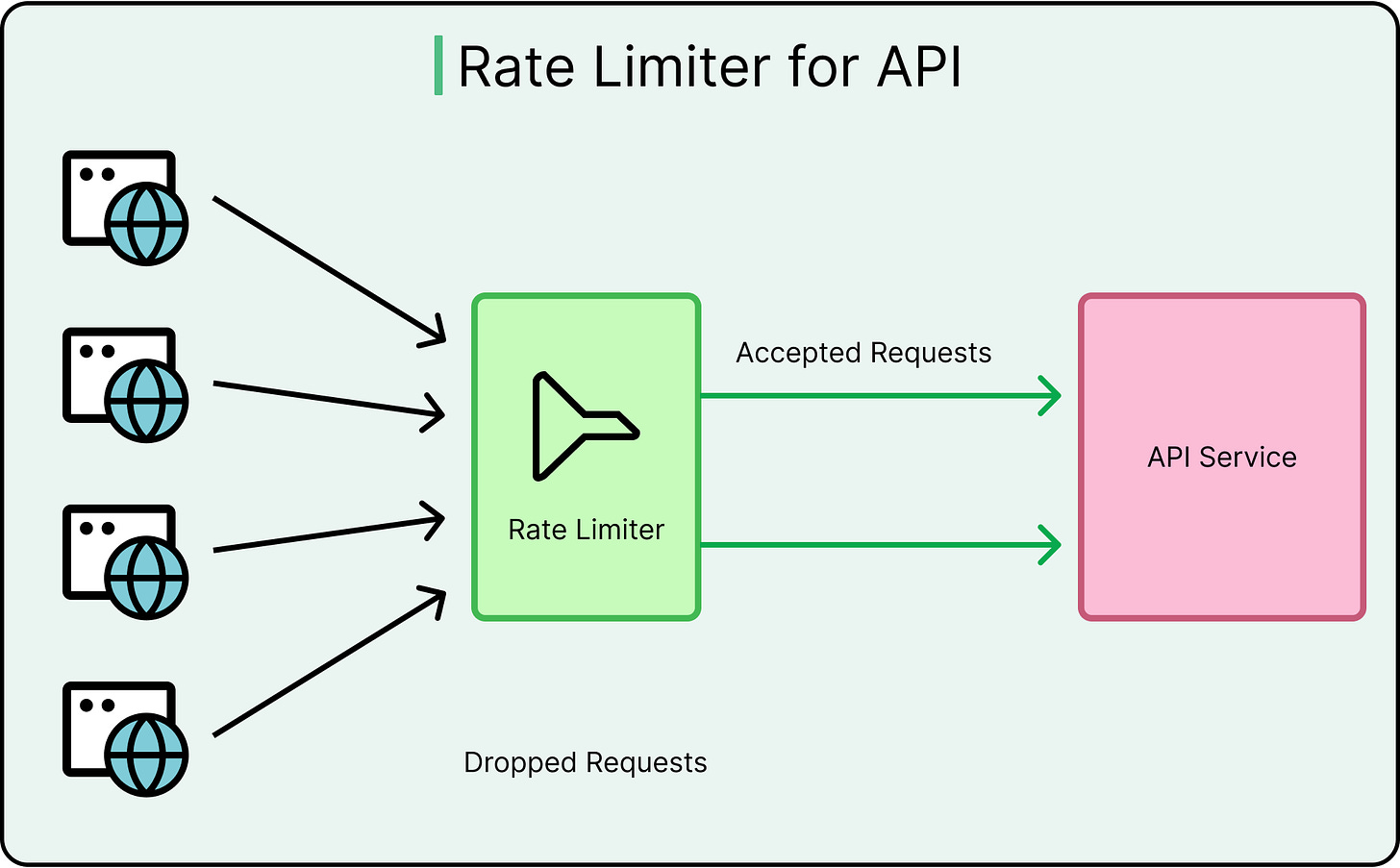

Rate Limiting and Abuse Protection

Even valid clients can behave badly, intentionally or otherwise. APIs must protect themselves from credential stuffing, data scraping, and denial of service attacks.

Rate limiting and throttling prevent these. They work by:

Capping request volume per client/IP/token.

Applying different thresholds for public vs internal clients.

Tracking requests over time windows (for example, 1000 requests per hour).

Tools like Nginx, Envoy, or API gateways can help enforce these policies.

Input Validation

Input validation is the first line of defense for an API.

Anything it receives from the outside (IDs, filters, search queries, or payloads) must be treated as untrusted. Failing to validate input can lead to SQL injection, script injection, path traversal, type mismatches, and crashes.

Validation happens in layers such as:

Transport-level: Reject malformed JSON and oversized payloads.

Schema-level: Enforce field presence, types, and formats (for example, using OpenAPI schemas)

Business logic: Apply domain-specific rules (for example, “cannot transfer money to self”)

Error Handling Should Not Reveal Everything

Error messages should help developers, not attackers. Detailed stack traces, SQL fragments, or internal identifiers in errors provide unnecessary insight.

Some examples of oversharing are as follows:

Error: SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = 'abc'::uuid failed

NullReferenceException at AuthService.Authenticate

Instead, APIs should use standard codes (400, 401, 403, 500) and return minimal, actionable messages. Log full errors internally, not in client responses. The less said externally, the harder it becomes to probe for weak spots.

HTTPS and TLS

Every API must use HTTPS. Without it, credentials can leak over the wire, session hijacking becomes trivial, and request data becomes visible to intermediaries.

Beyond TLS basics, security-conscious systems also:

Enforce HSTS (HTTP Strict Transport Security).

Pin certificates where appropriate.

Redirect all plaintext traffic automatically.

APIs built for production environments encrypt everything in transit. Anything less is a critical vulnerability.

Summary

In this article, we have looked at API design principles and techniques in detail with a special focus on REST. We’ve also looked at some ideas concerning gRPC to have a more holistic view.

Let’s summarize the key learning points in brief:

Well-designed APIs behave consistently, fail predictably, and grow without friction.

Consistent naming, structure, and method usage for APIs reduces mental overhead and simplifies client logic.

Resource-oriented paths and proper use of HTTP verbs help APIs align with expectations and standard tools.

Schema-first API design prevents drift, enables contract testing, and improves collaboration across teams.

Most security and reliability issues surface during retries, failures, or edge-case usage, not on the happy path.

Idempotency ensures safe retries by making repeated requests to produce the same result, especially for POST operations.

Idempotency keys allow clients to safely deduplicate operations with side effects.

APIs should support pagination to prevent performance bottlenecks and payload bloat. Some common pagination strategies are offset-based, cursor-based, and keyset-based.

Authentication identifies the caller, but authorization must be enforced per action and resource to avoid privilege leaks.

JWTs, OAuth2, and API keys offer different trade-offs in complexity, scope, and revocation.

Rate limiting protects APIs from abuse and must be tailored by client type and action sensitivity.

Input validation defends against malformed or malicious data across transport, schema, and business logic layers.

HTTPS is mandatory for all production APIs, along with the enforcement of TLS best practices.

Long-term API stability comes from designing for change, not just launch-day correctness.

Well crafted article for beginners and API architects. Good to keep this as a bible and point reminder during API design.

Nicely written