Every large system that spirals out of control starts the same way: small, functional, and deceptively simple. However, as the system evolves, things spiral out of control.

A feature is added here, a helper function squeezed there, and a “temporary” dependency for some urgent task that never gets removed. Months later, debugging requires going through five layers of indirection, and touching one module can break the entire system.

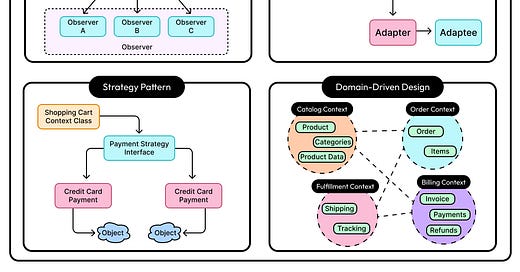

Behind the scenes of that slow collapse, two invisible forces often play tug-of-war: coupling and cohesion.

Most developers first hear these terms in textbooks or blog posts, often lumped into a “good design” checklist.

High cohesion: good.

Loose coupling: also good.

But beyond the concepts, the practical meaning often gets lost. What does coupling look like? When does cohesion break down in real teams? And why do some projects feel like a breeze to change, while others offer challenges with every pull request?

Coupling and cohesion aren’t abstract guidelines. They are practical engineering realities that define how easily code could evolve, how confidently teams could deploy, and how painful it becomes to onboard a new teammate or fix a bug under pressure.

In this article, we’ll attempt to understand coupling and cohesion in more realistic terms and how they might show up in different architectural styles and patterns.

Understanding Coupling

Coupling refers to how much one module depends on another.

The tighter the coupling between two modules, the more they need to know about each other’s internals: how they’re implemented, what assumptions they make, when they run, and what they return. The looser the coupling, the more independent those modules become, communicating only through well-defined interfaces or messages.

In other words, tight coupling makes systems rigid and loose coupling makes them flexible, but often harder to trace.

When a simple change triggers a cascade of issues across unrelated parts of the system, coupling is usually the culprit. The signs of coupling hide in plain sight: inside shared data structures and hardcoded dependencies. But when it breaks, everything breaks together.

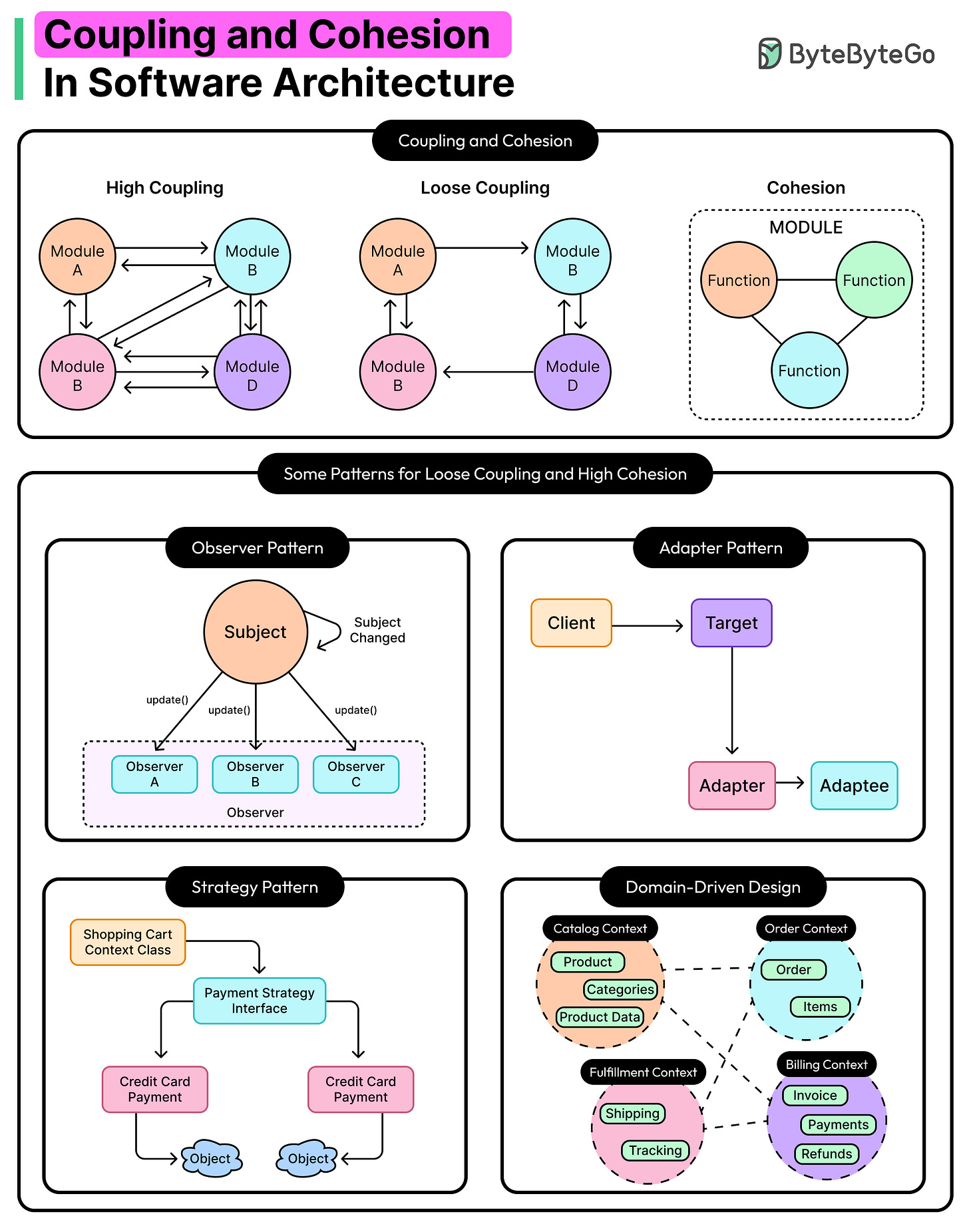

Tight Coupling

Tight coupling usually shows up when:

One module calls another’s internal methods or accesses its internal state directly.

A change in one module forces changes in others, even when their responsibilities seem unrelated.

Control flow and logic are spread across multiple classes that assume each other’s behavior.

See the diagram below that shows a representation of tight coupling in practice.

For example, a ProductController that constructs and manipulates a ProductRepository directly, not through an interface, not via inversion of control, but by hardwiring the exact class, creates tight coupling. If the repository changes (say, to fetch from a different database), the controller breaks. Unit tests suffer too, because mocking tightly coupled classes becomes difficult.

See the code example below:

// Tightly Coupled Example

public class ProductRepository {

public String getProductById(String id) {

// Simulate DB access

return "Product: " + id;

}

}

public class ProductController {

private ProductRepository repository;

public ProductController() {

// Direct instantiation = tight coupling

this.repository = new ProductRepository();

}

public void handleRequest(String productId) {

String product = repository.getProductById(productId);

System.out.println("Fetched: " + product);

}

}Note that this code example is just for demonstration purposes.

Tight coupling usually creeps in when developers choose convenience. Developers optimize for speed, skip abstractions, and “just call the method directly.” Over time, this results in increased coupling.

Still, not all tight coupling is bad. In performance-critical paths, tight integration may improve latency. Also, in early prototypes, it reduces the time to market. However, coupling tends to trade flexibility for immediacy, and that cost can grow with time.

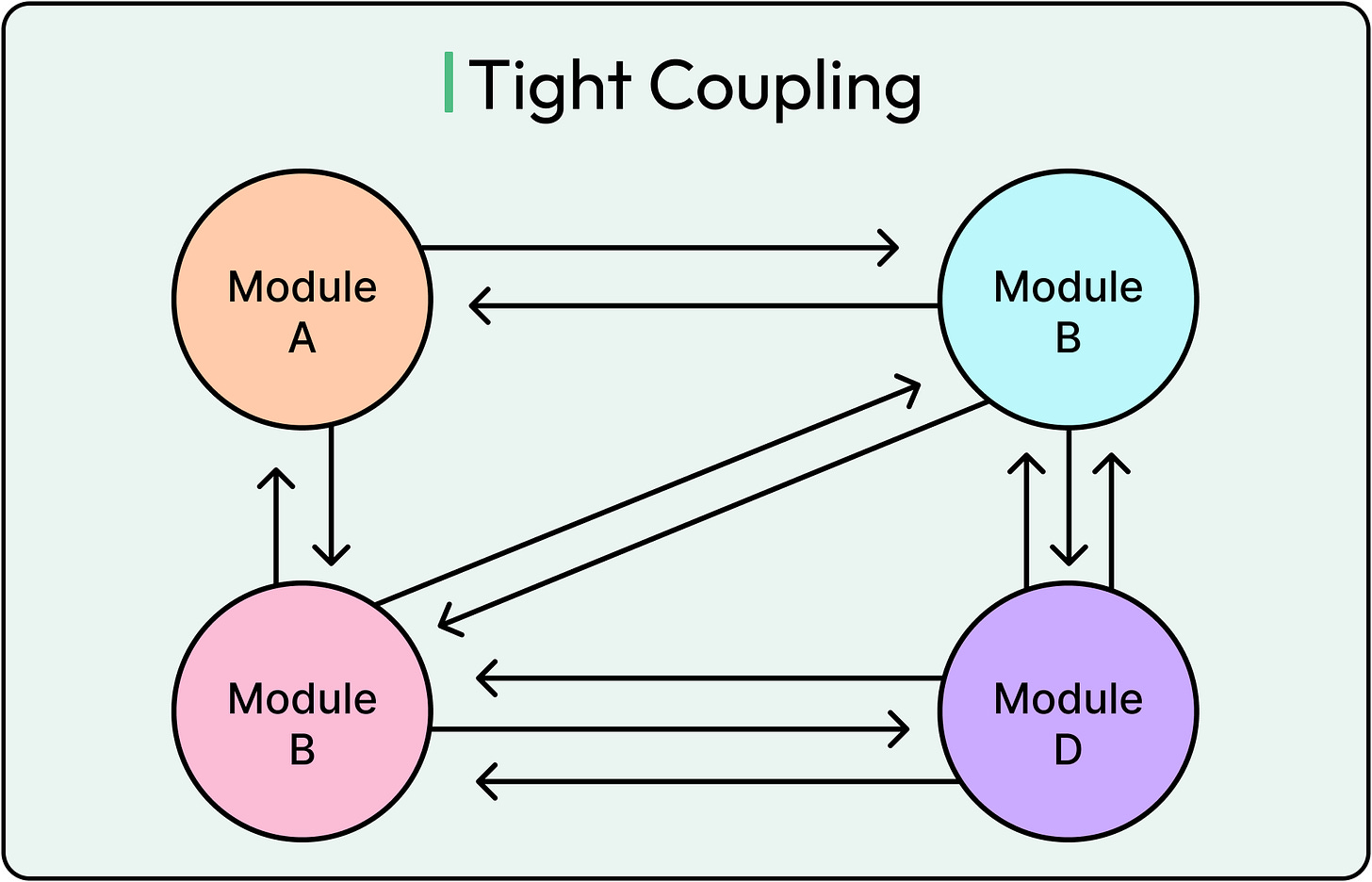

Loose Coupling

Two modules or components are said to be loosely coupled when:

Modules depend on interfaces, not concrete implementations.

Communication happens through events, messages, or abstract APIs.

Modules expose minimal surface area, just enough to get the job done and no more.

See the diagram below for a possible representation of loose coupling.

In a typical example, a UserService might depend on an INotificationSender rather than directly calling an EmailService. That shift decouples the business logic from the notification mechanism. Tomorrow, switching to SMS or a third-party API doesn’t touch UserService at all. The contract remains; the implementation evolves.

See the code example below for reference:

interface INotificationSender {

void sendNotification(String recipient, String message);

}

class EmailService implements INotificationSender {

@Override

public void sendNotification(String recipient, String message) {

System.out.println("Sending EMAIL to " + recipient + ": " + message);

}

}

class SmsService implements INotificationSender {

@Override

public void sendNotification(String recipient, String message) {

System.out.println("Sending SMS to " + recipient + ": " + message);

}

}

class UserService {

private INotificationSender notificationSender;

public UserService(INotificationSender notificationSender) {

this.notificationSender = notificationSender;

}

public void registerUser(String username) {

// Simulate user registration logic

System.out.println("Registering user: " + username);

notificationSender.sendNotification(username, "Welcome to the platform!");

}

}

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Use EmailService

INotificationSender emailSender = new EmailService();

UserService emailUserService = new UserService(emailSender);

emailUserService.registerUser("alice@example.com");

System.out.println();

// Swap to SmsService without touching UserService

INotificationSender smsSender = new SmsService();

UserService smsUserService = new UserService(smsSender);

smsUserService.registerUser("555-1234");

}

}Loose coupling improves testability, modularity, and reuse. But it also spreads logic across boundaries, which can increase complexity. In distributed systems, loose coupling comes at the cost of observability and latency

The Trade-Off

Coupling isn’t inherently good or bad. It’s a constraint that has to be managed as part of the project. A few points to keep in mind are as follows:

Tighter coupling works when simplicity, speed, or co-location matter. Loose coupling wins when change is constant and boundaries matter more than call speed.

Too much coupling, and every deploy becomes risky. Teams can’t move independently. On the other hand, if there’s too much abstraction in pursuit of loose coupling, clarity suffers. Engineers can struggle to trace a feature across five interfaces and three DI bindings.

Coupling decisions impact system boundaries, team velocity, and incident response. Therefore, they should be deliberate and meaningful. Design begins with one question: “What kind of change is this system likely to face?” The answer determines how tight or how loose the coupling should be.

Cohesion: The Glue That Holds A Module Together

Some modules feel intuitive at first glance. Their classes work together toward a clear goal. Their methods appear clear and understandable. Making changes feels easy and safe from an impact point of view.

One of the reasons this happens is because of cohesion.

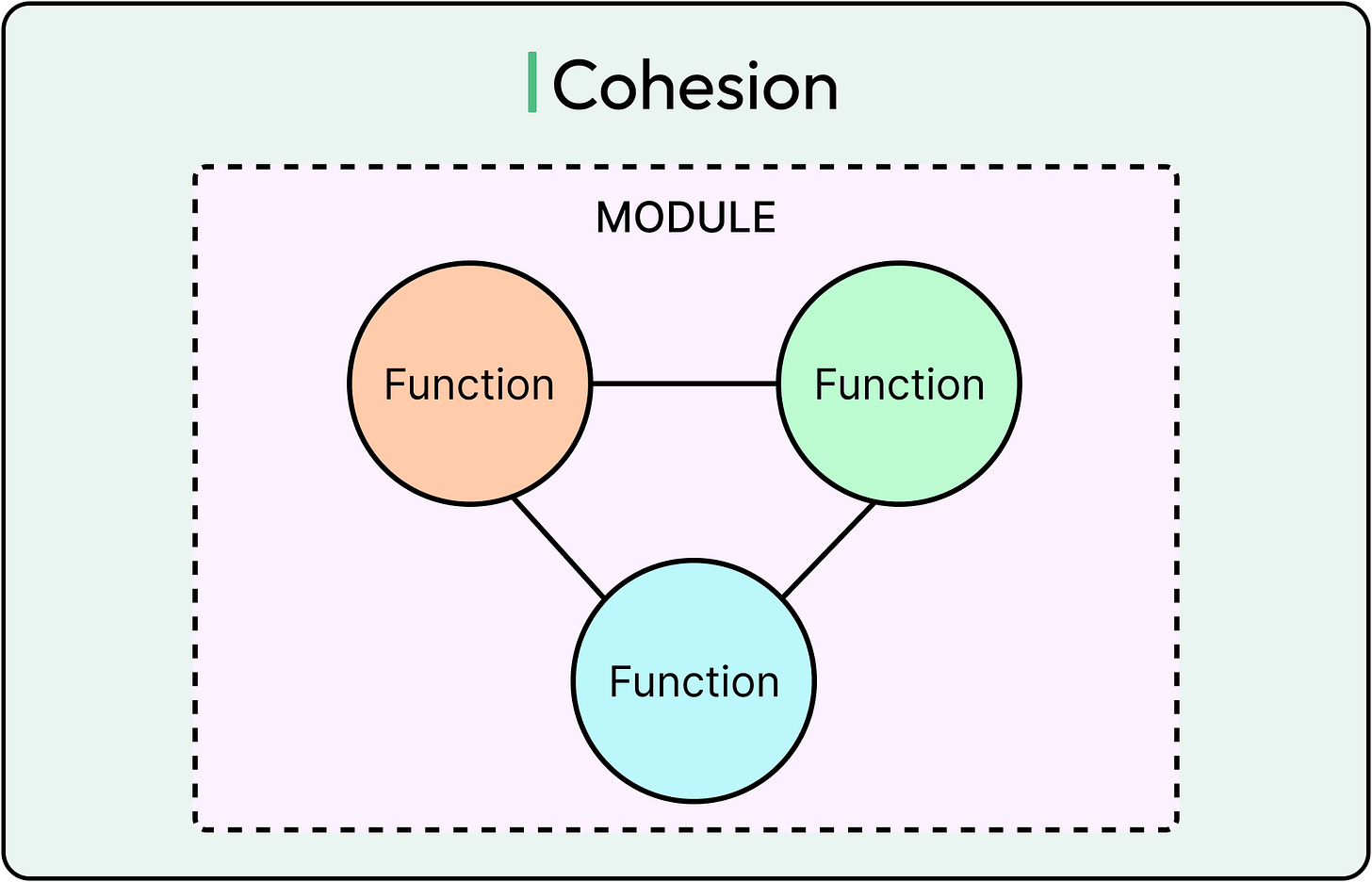

Cohesion describes how tightly related the responsibilities inside a module are. A highly cohesive module focuses on a single purpose. Every function, class, and variable exists to support that purpose. A low-cohesion module mixes unrelated concerns, often because responsibilities have drifted over time or weren’t clearly defined to begin with.

If coupling defines how much a module depends on others, cohesion defines how well a module stands on its own.

See the diagram below that tries to show the concept of cohesion.

Low Cohesion

Low cohesion often sneaks in when teams optimize for reuse or try to "group related things" too early. It shows up in catch-all service classes, bloated controllers, and utility files that handle everything from database access to date formatting.

Consider a UserManager class that handles:

Creating and updating user records

Authenticating logins

Sending password reset emails

Logging suspicious activity

Caching user sessions

At first, this might feel convenient. Everything about “users” lives in one place. But the responsibilities vary wildly. Business logic, security, infrastructure, and communication all sit in the same module, tightly entangled. Testing becomes fragile, and changes ripple unpredictably. For example, a tweak to the cache logic might accidentally break email notifications.

Low cohesion tends to:

Increase cognitive load: Developers must understand multiple concepts to change one.

Introduce hidden dependencies: Methods rely on side effects of unrelated logic.

Encourage spaghetti architecture: Everything depends on everything else.

Worse, when these bloated modules get reused, their internal coupling spreads into other parts of the system, creating accidental coupling between components that only needed a small piece of shared logic.

High Cohesion

A cohesive module draws a clear boundary around its responsibility. It encapsulates one purpose, does it well, and offers a minimal interface to the outside world. Internally, its components are tightly aligned. Externally, it remains simple and predictable.

For example, take a TokenService that only handles JWT creation, validation, and expiration. It doesn’t care about user credentials, logging, or cookies. Those concerns belong elsewhere. Such a narrow focus means:

Tests are easy to write and understand.

Internal changes rarely affect external code.

Reuse feels natural, not forced.

Cohesion doesn’t necessarily mean tiny modules. It is about relatedness, not size. A module can be large and still cohesive if all the parts serve a unified purpose. Conversely, breaking up logic into many small but unfocused files doesn’t help.

The Role of Naming and Boundaries

Poor cohesion often stems from vague naming and unclear ownership.

When a module’s name (Utils, Helper, Manager) doesn’t reveal its purpose, it usually doesn’t have one. Strong cohesion starts with naming: “What does this module exist to do?”

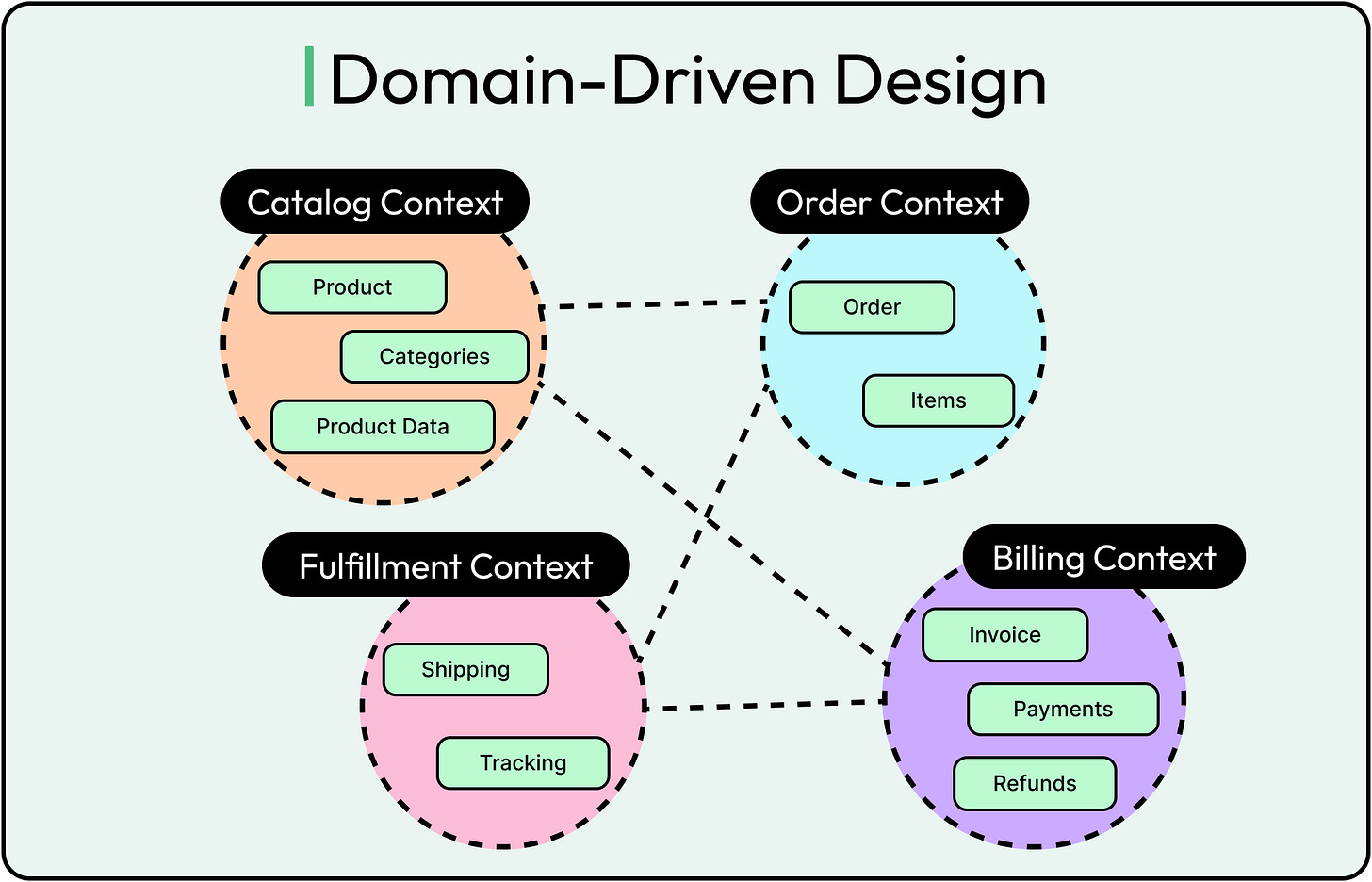

A well-defined domain boundary also promotes cohesion. In Domain-Driven Design, the concept of a “bounded context” exists for this reason. It gives each module a clearly defined area of responsibility, limiting the scope of ambiguity.

See the diagram below that shows the concept of bounded contexts in DDD.

Coupling and Cohesion

Coupling and cohesion are tightly linked concepts. They push and pull against each other, and when balanced well, they form the backbone of clean, adaptable systems.

Coupling looks outward: how much a module relies on others.

Cohesion looks inward: how well a module aligns with its intended role.

A design that solely optimizes for one while ignoring the other tends to break in subtle ways.

High Cohesion Can Expose Coupling

A cohesive module draws a sharp boundary around a specific responsibility. That’s good. But the sharper the boundary, the more pressure it puts on communication with other parts of the system.

Consider a well-designed BillingService that handles invoicing, tax calculation, and payments. Its logic is tight and coherent. But if ten other services all depend on it directly (calling methods, sharing data structures, or reaching into its internals), the system is now tightly coupled to billing. Any internal change risks a cascade of breakages.

Cohesion makes a module easier to understand and reason about. But unless it’s paired with thoughtful interfaces and contracts, other modules can become overly dependent on it, creating fragile coupling.

Loose Coupling Can Obscure Cohesion

The flip side is also common: developers chasing decoupling end up scattering logic across multiple layers, classes, or services. Everything talks through abstractions. Dependencies are injected. Event buses handle communication. And yet, despite all this indirection, the logic itself remains blurry.

For example, take a microservices setup where the user registration process touches five services: one handles identity, another triggers emails, a third logs the activity, a fourth updates a CRM, and a fifth provisions cloud storage. Each service is loosely coupled. But together, they form a brittle setup with no clear owner of the process.

This is where cohesion suffers. The business logic (what happens when a new user signs up) gets lost across boundaries. Debugging becomes harder, and ownership becomes murky. The coordination overhead grows. This is where the concept of bounded contexts becomes important.

Loose coupling improves flexibility, but without cohesion, the system starts to feel hollow: modular on paper, chaotic in practice.

The Sweet Spot: Local Focus, Global Independence

Coupling and cohesion aren’t independent dials to be tweaked in isolation. They’re part of the same system. When one shifts, the other reacts.

The goal shouldn’t be to maximize cohesion or minimize coupling in isolation. The goal is modularity: small, focused units that interact through clear, minimal contracts.

Well-structured systems tend to follow this shape:

Internally cohesive: Each module owns a clear responsibility and has internal consistency.

Externally decoupled: Modules depend on each other through stable interfaces, not hidden knowledge.

Some signs that the balance is working are as follows:

A change to one module requires minimal changes elsewhere.

Features map cleanly to one or two components.

Onboarding developers can understand a module without the need to understand the whole system.

Measuring Coupling and Cohesion

As mentioned, coupling grows when modules rely too heavily on each other’s structure, behavior, or lifecycle. While no module exists in isolation and some dependency is necessary, problems arise when that dependency becomes rigid or implicit.

Some ways coupling can be measured are as follows:

Fan-in and Fan-out: Modules with a high number of inbound or outbound connections tend to be risk zones. A high fan-in indicates that many modules depend on this one. Any change carries ripple effects. A high fan-out suggests the module itself depends on many others, making it fragile and hard to reuse.

Change Propagation: Frequent commits that touch the same group of files, even across features, often point to tight coupling. When a small change demands edits in multiple modules, boundaries are probably unclear.

Coupling Between Objects (CBO): This static analysis metric counts how many other classes a particular class is coupled to. A high score doesn't always mean bad design, but it signals areas worth inspecting.

Runtime Coupling: Dynamic dependencies, such as services that call each other in production, can be traced using observability tools. Service meshes, tracing tools (for example, Jaeger, Zipkin), and structured logging can reveal hidden entanglements between microservices.

Cohesion is harder to measure directly. It’s about how well a module’s internal components support a single, well-defined responsibility. A few indicators can help:

Lack of Cohesion in Methods (LCOM): This is one of the oldest cohesion metrics. It measures how often methods in a class operate on the same set of fields. High LCOM means methods are doing unrelated things, often a sign of weak internal consistency.

Semantic Diffusion: If explaining what a module does takes more than one clear sentence, or if that sentence includes “and also”, cohesion is probably suffering. This isn’t a metric a tool can compute, but it's a useful verbal check.

Churn vs. Complexity: Modules that change often and are also complex tend to have low cohesion. They're doing too much, and each change touches unrelated logic. Tools like SonarQube can help visualize these hotspots using historical data.

Test Scope Clarity: Well-cohesive modules are easy to test in isolation. If tests constantly mock unrelated dependencies or touch too many behaviors, the module probably lacks cohesion.

No metric tells the whole story. High coupling doesn’t always mean bad design. Some modules act as integration points by necessity. Also, low cohesion isn’t always a bug. Sometimes, legacy systems force broader responsibilities.

The key is using metrics as guidance:

Use them to find candidates for review, not to gate deployments.

Compare modules over time to spot worsening trends, not one-time spikes.

Combine static metrics with human context: ownership, domain knowledge, and user impact.

Design Patterns That Encourage Loose Coupling and High Cohesion

Design patterns often encode battle-tested solutions to recurring architectural problems. Some of them exist specifically to help decouple modules, clarify responsibilities, and reduce the cost of change. When used with care, these patterns strengthen cohesion inside components and loosen the coupling between them.

Let’s look at a few such design patterns:

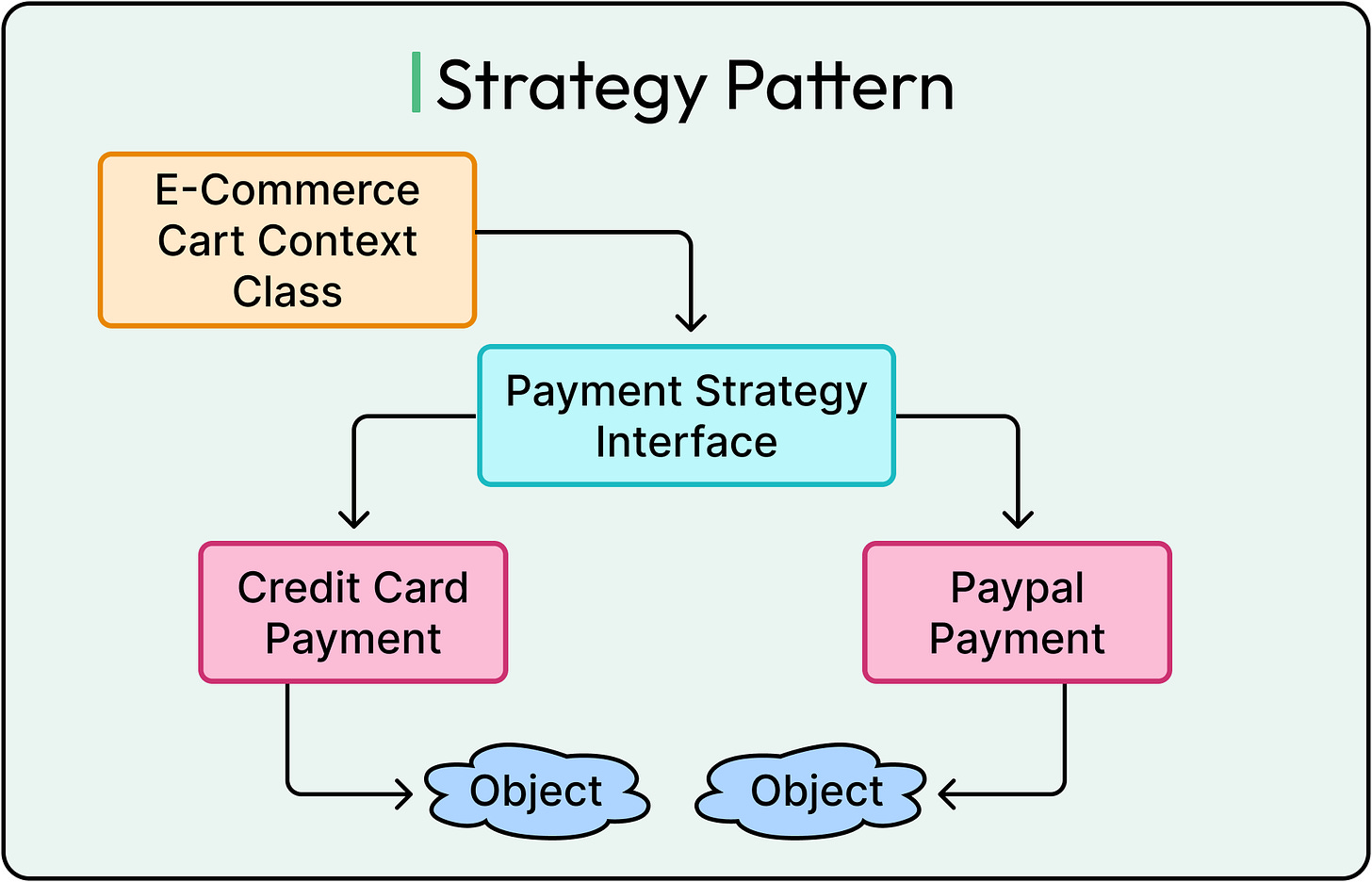

Strategy Pattern

When a module needs to perform a task that could vary, but the surrounding logic stays the same, the strategy pattern keeps things cohesive and decoupled.

Instead of hardcoding behavior, the module delegates it to a strategy interface. Each strategy implements the same contract but behaves differently and supports high cohesion. Also, since the caller depends only on an interface, it encourages loose coupling.

See the diagram below:

This pattern is good for handling business logic that needs to change frequently. It also helps avoid if-else or switch blocks full of behavioral branching.

However, the pattern can introduce indirection. For simple cases, it may feel like overengineering. It pays off well when variations grow.

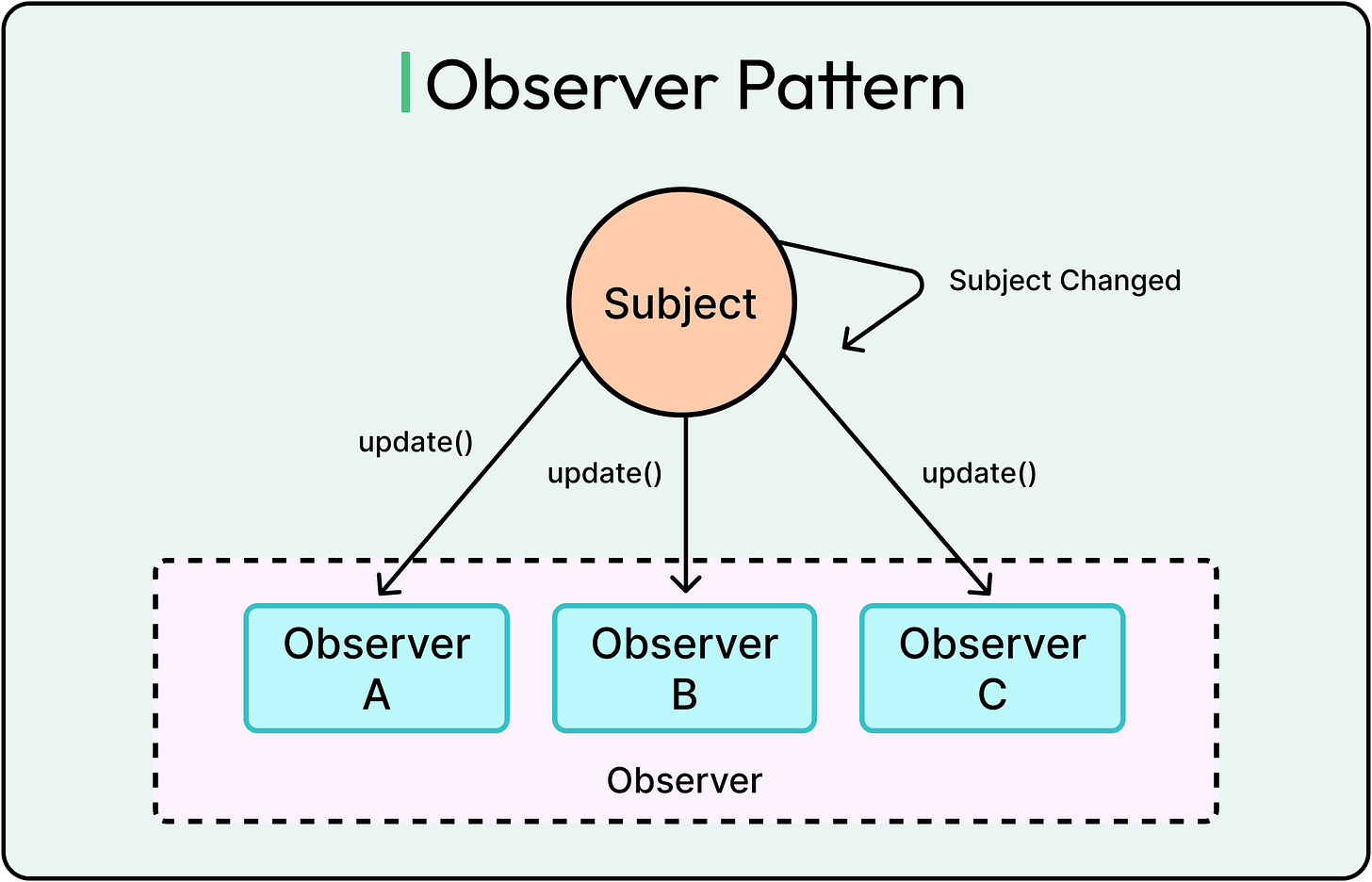

Observer Pattern

When one module needs to react to changes in another, but without knowing who or how, observer decouples them via publish-subscribe behavior.

In this pattern, a subject exposes events. Observers subscribe and respond when those events occur. These observers can be added, removed, or modified without touching the subject, encouraging loose coupling. Also, the logic stays cohesive within each observer.

See the diagram below:

This pattern is often used when UI updates are triggered by model changes. Also, it is common in event-driven systems where multiple components react to a single change.

The downside of this pattern is that it becomes harder to reason about control flow. Debugging event chains across dozens of observers can be difficult.

Dependency Injection

Instead of hardcoding dependencies, dependency injection (DI) lets a container or caller supply them. This pattern separates what a class does from how it gets the tools required to do the job.

It helps systems with lots of interchangeable components. Also, it is useful in testable code that needs to swap real dependencies for mocks or fakes.

With DI, classes depend on interfaces rather than implementations, thereby reducing coupling. Also, business logic focuses on its job and not on constructing dependencies, thereby increasing cohesion.

On the downside, DI frameworks can introduce hidden complexity and startup indirection. When abused, they create unclear wiring and debugging challenges.

Facade Pattern

When multiple modules interact with a messy or low-level API, a facade wraps that complexity in a clean, unified interface.

This is great for integration with legacy systems, SDKs, or deeply nested internal libraries. It helps reduce coupling between business logic and infrastructure.

Facades support loose coupling since consumers deal with one clean interface, instead of multiple fragmented ones. Also, the facade manages the orchestration, keeping external callers focused and thereby encouraging cohesion.

The risk involves a facade becoming too large or too leaky if not carefully scoped.

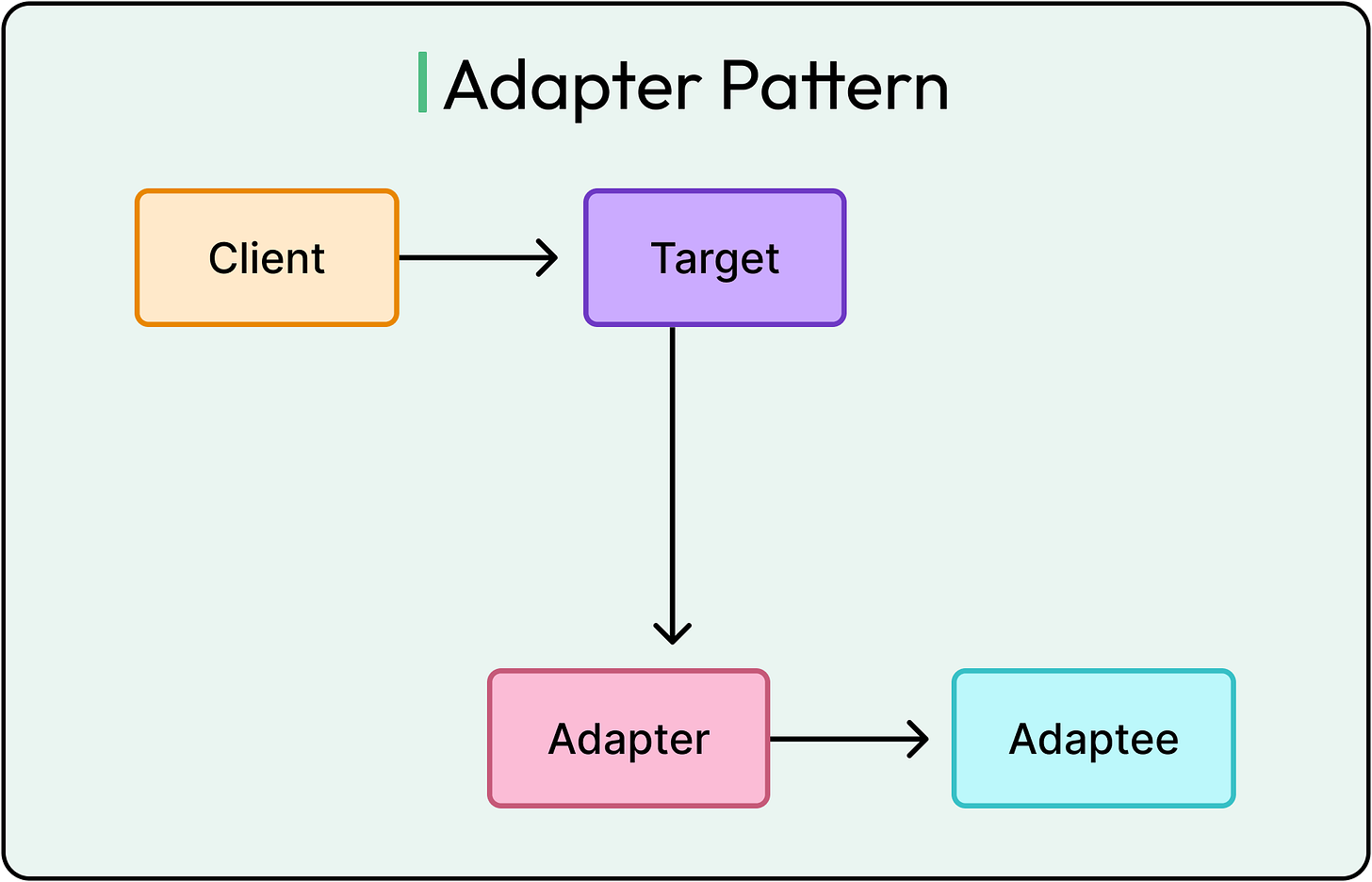

Adapter Pattern

Adapters wrap one interface to match another, allowing components to talk without being directly compatible.

They help integrate third-party libraries without polluting internal code. Also, it can support multiple implementations under a single abstraction.

Since the systems depend on internal contracts, the facade pattern encourages loose coupling. Also, the translation logic stays in one place, supporting high cohesion. The trade-off is that additional layers can obscure behavior, and their benefit depends on long-term variability.

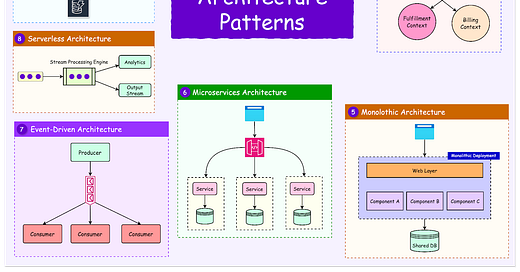

Coupling and Cohesion in Popular Architectural Styles

Understanding how coupling and cohesion behave across popular architectural styles helps avoid common failure modes such as rigid services, leaky layers, brittle APIs, and systems that are modular in theory but entangled in practice.

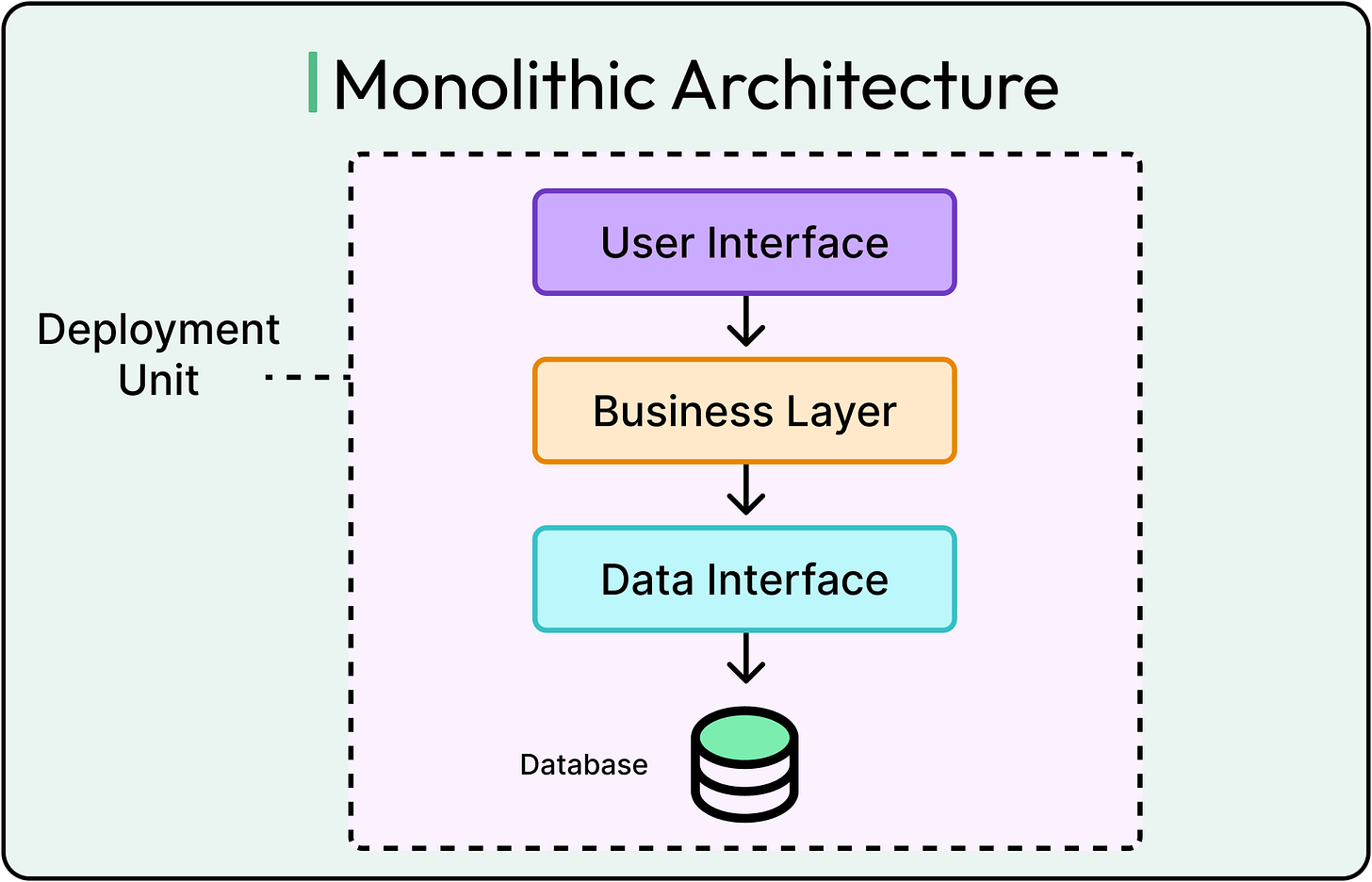

Monoliths

Monoliths concentrate logic in one deployable unit.

This co-location makes it easier to share data, call methods, and trace code paths. It also makes it tempting to blur boundaries.

See the diagram below:

Here’s how cohesion and coupling work in a typical monolithic setup:

Cohesion in monoliths tends to be easier to maintain early on. Related logic lives in the same codebase, can share types, and often shares language-level context (for example, a common ORM or framework).

Coupling, however, grows silently. Without a strong modular design, different features and domains start depending on each other’s internals via direct calls, shared states, and tight layering. Over time, the monolith becomes a distributed system in disguise, with implicit dependencies and high coordination costs.

Adding or changing a feature triggers ripple effects. Refactoring becomes risky, and ownership blurs. Teams step on each other’s code, even when working in separate domains.

Enforcing modularity within the monolith can help alleviate these challenges. Use clear domain boundaries, module interfaces, and layered contracts, even if everything ships together.

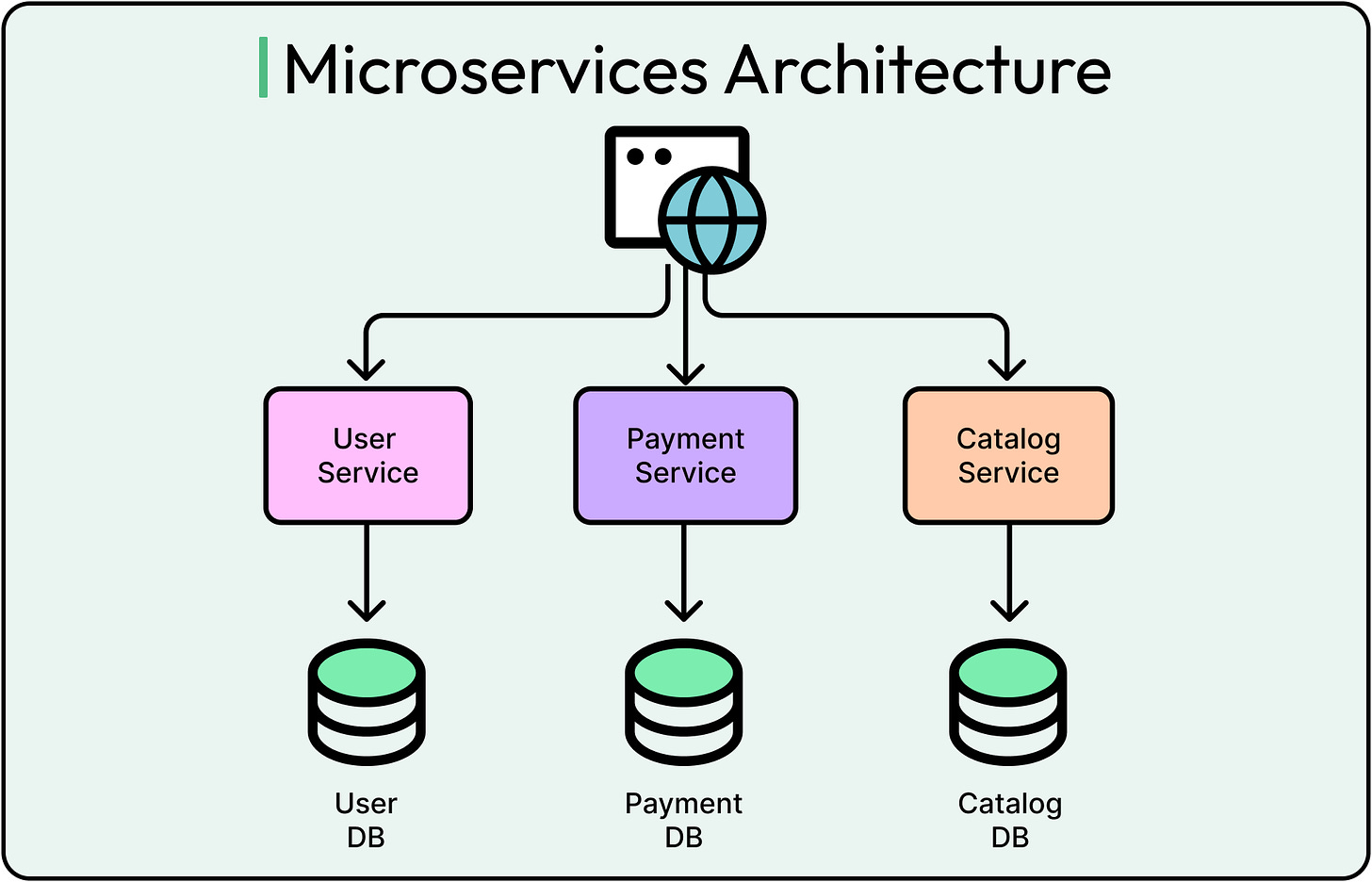

Microservices

Microservices enforce physical separation where each service lives in its process, communicates over the network, and owns the data.

Here’s how this pattern impacts coupling and cohesion.

Coupling is reduced at the infrastructure level. Services talk through APIs, not method calls. Shared state becomes harder intentionally, making dependencies more explicit and evolution safer.

Cohesion becomes critical. Each microservice must own a single, well-defined responsibility. Without that, the system fragments into tiny, chatty services that collaborate poorly and fail together.

If service boundaries are cut by technical concerns instead of domain logic (for example, “auth service” + “email service” + “user details service”), cohesion suffers. No single service owns the whole business workflow, and the system relies heavily on coordination.

Use domain-driven design (DDD) to define bounded contexts. Treat services as independently deployable business capabilities, not just APIs.

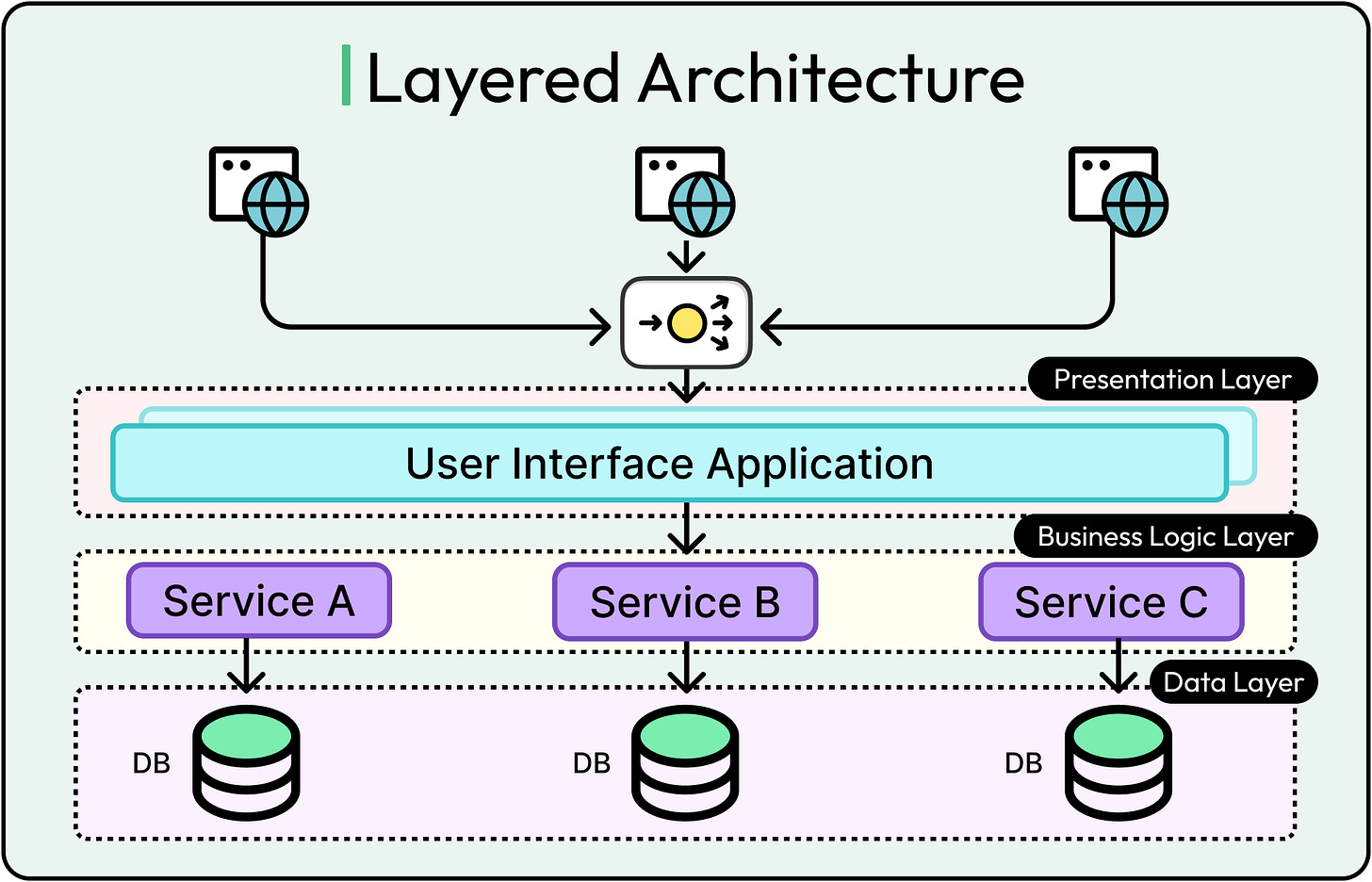

Layered Architecture

Layered or “n-tier” architecture (presentation, business logic, data access) has been the default pattern for decades. It structures code by technical responsibility, not business domain.

Here’s how this pattern impacts coupling and cohesion:

Cohesion within layers depends on discipline. Ideally, each layer does one thing: render views, apply rules, and persist data. But in practice, logic often leaks. Services start making UI decisions. Controllers validate business rules. DAOs handle formatting.

Coupling tends to grow vertically. Higher layers call lower layers directly. Any change in the data model can impact business logic and UI. This creates temporal coupling in the sense that layers need to change and deploy together.

Large systems with layered architectures often suffer from “God services” or “fat controllers” because no layer owns domain logic. Testing becomes difficult because of too many layers to mock and unclear responsibility boundaries.

To handle these challenges, invert dependencies where needed (for example., use-case-driven services calling out to infrastructure). Encapsulate domain logic in its cohesive layer. Treat the business model as the center, not an afterthought.

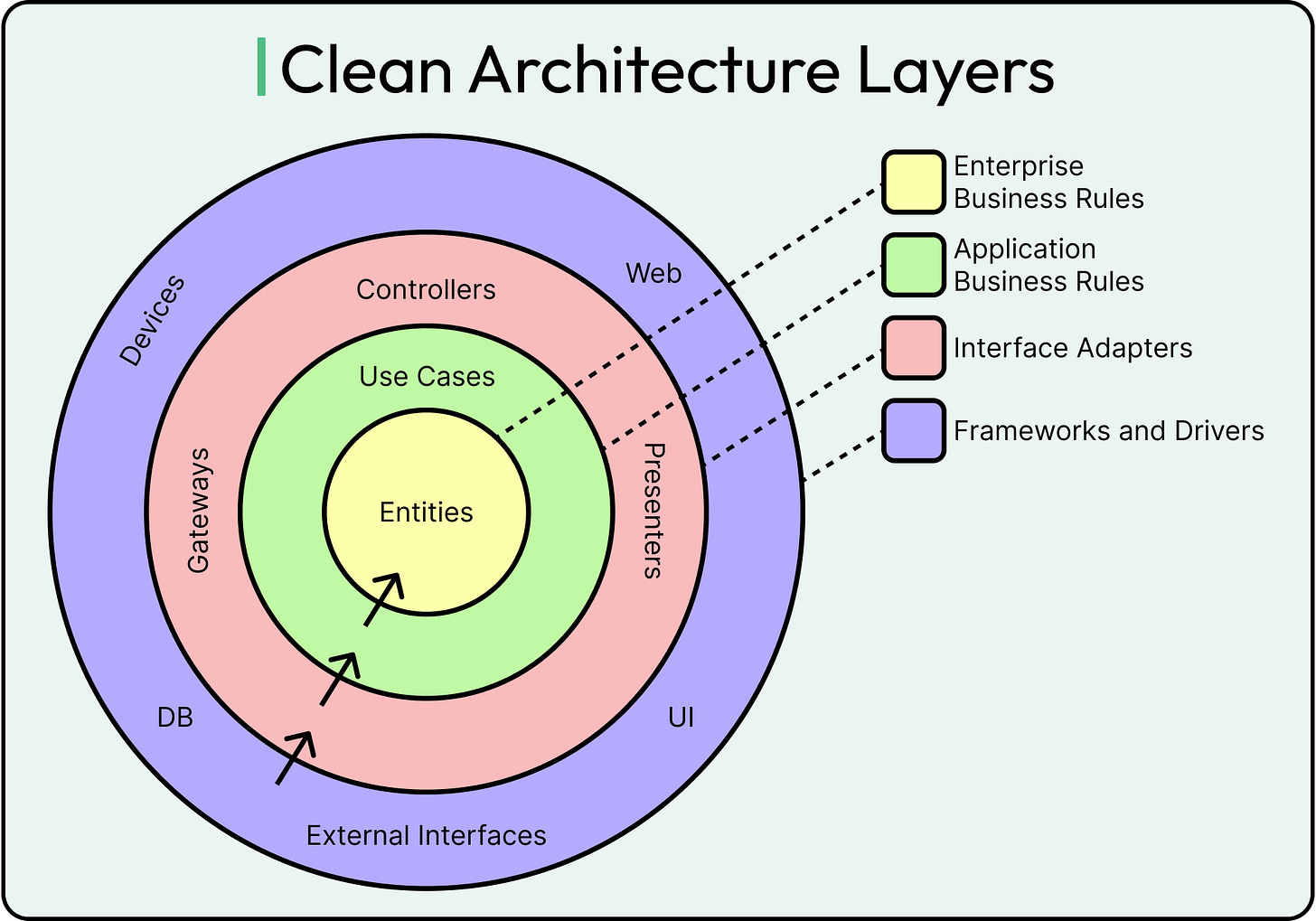

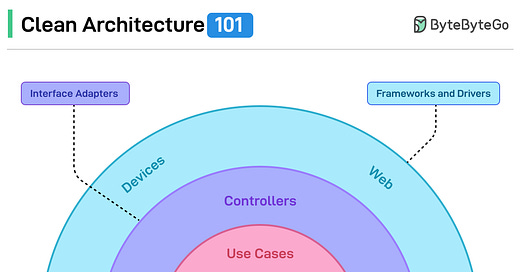

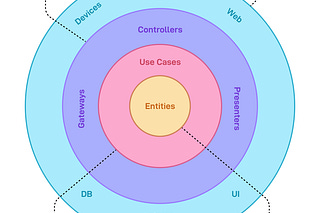

Clean Architecture

Clean Architecture flips traditional layering on its head. Instead of organizing code by technology, they organize it by use-case and domain, pushing infrastructure to the edges.

See the diagram below:

Here’s how clean architecture impacts cohesion and coupling:

Cohesion is intentionally high within the domain layer. All core business logic lives here, independent of databases, frameworks, or transport protocols.

Coupling is explicitly controlled through interfaces. The domain depends on abstractions, and adapters (such as controllers, databases, and message brokers) implement those contracts from the outside.

Initial complexity can feel heavy for small teams or MVPs. Writing abstractions before real behavior exists can lead to overengineering or vague boundaries.

The goal should be to start simple and focus on isolating business rules. Avoid premature abstraction. Only introduce interfaces where change is likely or infrastructure is volatile.

Takeaway

No architecture can have perfect coupling or cohesion. Each one makes trade-offs between speed and stability, flexibility and clarity, short-term delivery and long-term maintainability.

Monoliths make cohesion easier, but coupling is increased.

Microservices force decoupling but demand strong cohesion.

Layered architectures clarify technical roles but often blur domain ownership.

Hexagonal designs elevate business logic but require clear intent.

Choosing the right architecture means asking hard questions: Where is change expected? Who owns which domain? How often will these modules evolve independently?

The better those questions are answered, the more likely the architecture will serve the system, not the other way around.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at coupling and cohesion in detail along with how these concepts play out in different patterns and architecture styles.

Let’s summarize the key learning points in brief:

Coupling describes how much one module relies on another. Tight coupling increases fragility and coordination cost, while loose coupling allows modules to evolve independently through clear interfaces.

Cohesion measures how well the responsibilities within a module align. High cohesion makes code easier to understand, test, and change; low cohesion leads to confusion and entangled logic.

Tight coupling often creeps in silently through direct dependencies, shared internal state, and implicit assumptions between components.

Loose coupling favors change and modularity, but can introduce complexity and debugging overhead if the boundaries aren't managed.

Low cohesion turns modules into junk drawers of unrelated responsibilities, making testing harder and increasing the likelihood of accidental coupling.

High cohesion keeps code focused, limits side effects, and helps engineers reason locally about behavior and intent.

Coupling and cohesion must be balanced. Optimizing for one while ignoring the other can lead to brittle or incoherent systems.

Metrics like CBO, LCOM, fan-in/fan-out, and change frequency can help diagnose structural problems, but they must be interpreted in context, not followed blindly.

Design patterns such as strategy, observer, and dependency injection are effective tools for reducing coupling and increasing cohesion when applied thoughtfully.

Different architectural styles make different trade-offs. Monoliths risk hidden coupling, microservices demand cohesive boundaries, layered architectures can blur responsibilities, and clean architecture emphasize separation and clarity.

Modularity is the ultimate goal. Systems with high internal cohesion and low external coupling are easier to change, scale, and understand over time.

Good design anticipates change. Decisions about structure, boundaries, and dependencies should reflect how the system is expected to evolve.

Great article! I believe that knowing how to reason about the system semantics on different fronts than just the technical one is paramount if we are to build collaboratively in an effective way.