Most software doesn’t break because of syntax errors or flawed if-else logic.

It breaks because teams lose alignment with the business problem they’re supposed to solve. Systems become tangled with technical assumptions that age poorly. Features get implemented without proper design considerations. And over time, every new requirement creates more issues that keep piling up.

Often, this isn’t a tooling problem. It’s a modeling problem.

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) tries to tackle this problem head-on. At its core, DDD is a way of designing software that keeps the business domain, not the database schema or the latest framework, at the center of decision-making. It insists that engineers collaborate deeply with domain experts during the project lifecycle, not just to gather requirements once and vanish into Jira tickets. It gives teams the vocabulary, patterns, and boundaries to model complex systems without getting buried in accidental complexity.

Of course, DDD is not a silver bullet. It doesn’t generate code, and it won’t magically fix a legacy monolith. But it does offer something more valuable in the long run: clarity around what the system is supposed to do and where it’s allowed to change.

This approach becomes especially valuable when:

The domain is non-trivial and keeps evolving. Think finance, healthcare, logistics, or giant marketplaces.

Multiple teams are working on overlapping parts of the system.

Code needs to reflect real-world behavior, not abstract technical constructs.

DDD doesn’t care whether the architecture is monolithic or microservice-based. What it does care about is whether the model reflects the real-world rules and language of the domain, and whether that model can evolve safely as the domain changes.

In this article, we explore the core ideas of DDD (such as Bounded Contexts, Aggregates, and Ubiquitous Language) and walk through how they work together in practice. We will also look at how DDD fits into real-world systems, where it shines, and where it can fall flat.

What is Domain Driven Design?

Domain-Driven Design isn’t a framework. It doesn’t ship with starter templates or ready-made components.

Instead, it’s a way of thinking about how to build software that aligns tightly with the business problems it’s supposed to solve. In other words, the concern revolves around the domain: the real-world logic, rules, constraints, and language that shape what the system does.

The “design” part isn’t about wireframes or UI. It’s about shaping the core model of the system so that it reflects the mental model of domain experts or the people who understand the problem space best. The goal is simple, even if the execution isn’t: design the software’s structure to match the domain’s structure.

Eric Evans, who first formalized DDD in his 2003 book, framed it like this: the heart of software isn’t infrastructure or code reuse. It’s the domain model. And that model has to be carefully distilled, refined, and protected as the system grows.

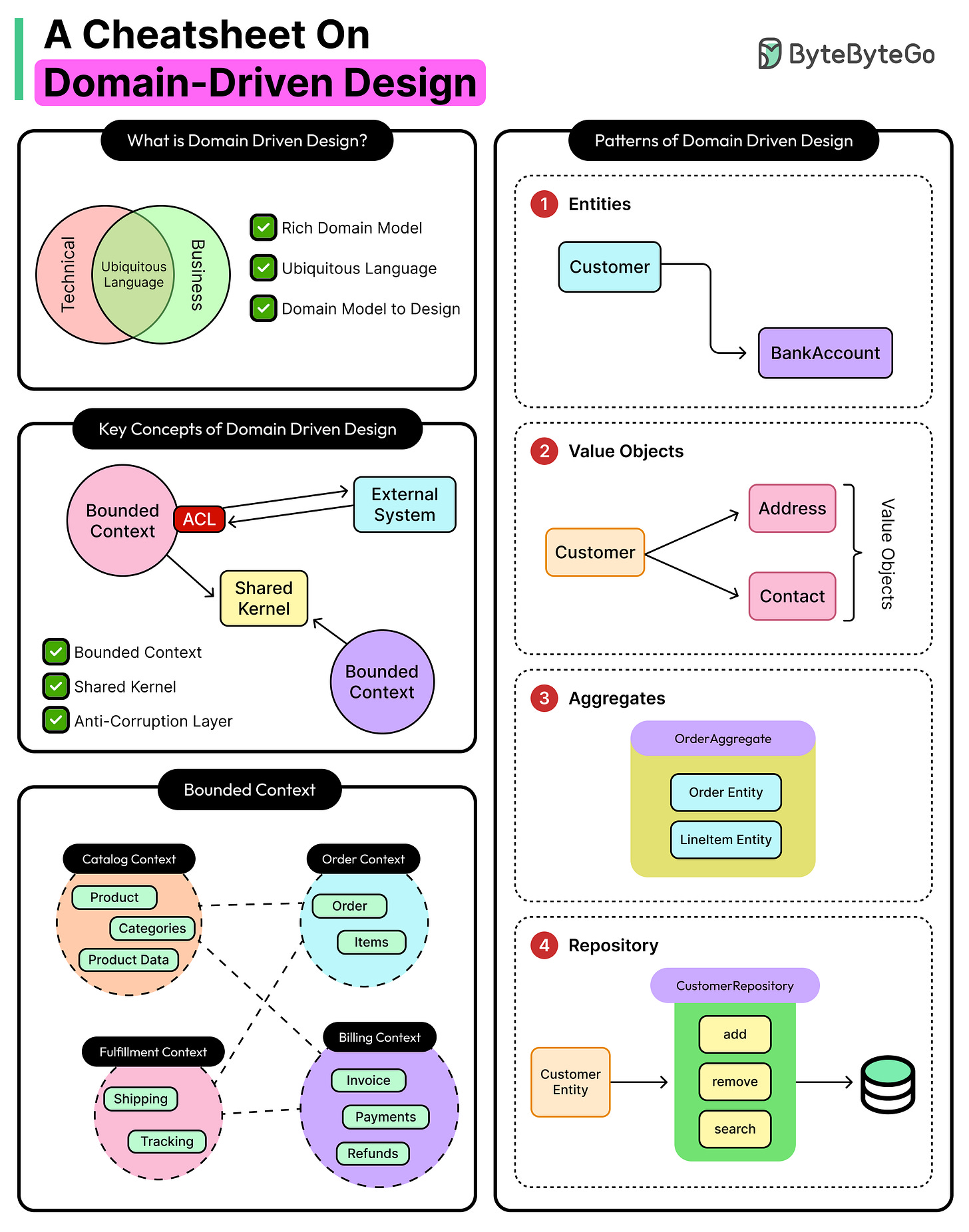

In practice, DDD focuses on three essential outcomes:

Deep alignment between developers and domain experts. The system only behaves correctly when everyone agrees on what “correct” means. That shared understanding has to show up in both conversation and code.

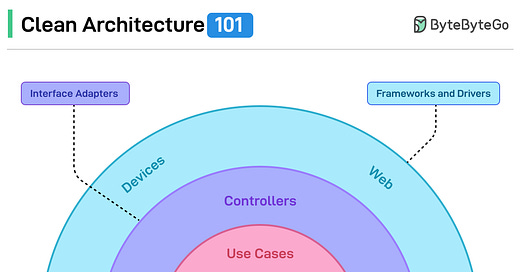

Clean separation of concerns. The business rules that define how the system should behave must be isolated from glue code, infrastructure, or delivery details. They deserve to live in a space of their own.

Explicit boundaries around different parts of the domain. Not everything fits into one giant model. Different areas of the system often follow different rules, workflows, and terms. DDD makes those differences explicit and enforces them with clear edges.

This doesn’t mean DDD is only for large teams or enterprise-scale projects.

Even a small codebase can benefit from separating concerns, using precise language, and avoiding conceptual soup. However, the real power of DDD shows up when complexity starts to spiral and when business logic gets layered, workflows cross team lines, and every change has a high impact.

Let’s now understand some key concepts that shape DDD.

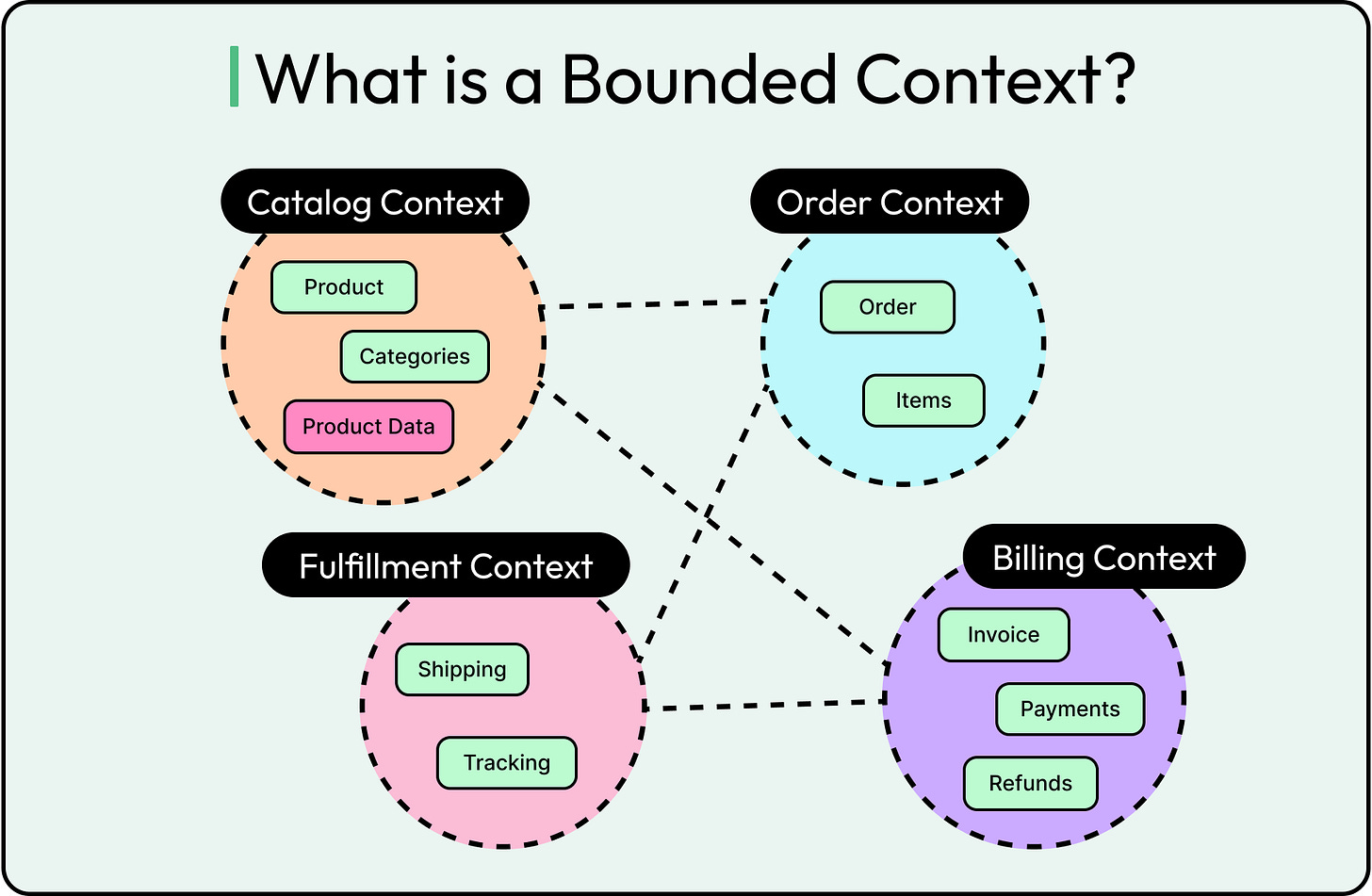

Bounded Contexts

Every large system eventually turns into a semantic battleground. One team says “Customer,” and they mean a paying subscriber. Another team uses “Customer” to describe anyone with a profile, even if they’ve never spent a single dollar. Both are technically right. However, both are dangerously wrong in the wrong context.

This is where Bounded Contexts help.

A Bounded Context defines where a specific domain model applies and where it doesn’t. It’s a semantic boundary (not just a code module or service) where terms, rules, and logic are guaranteed to make sense within that space, and only within that space. Outside of it, all bets are off.

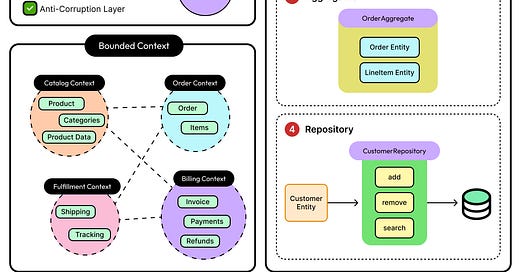

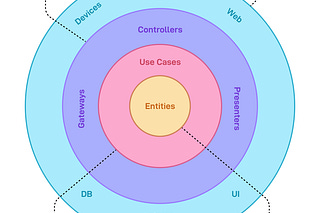

The diagram below shows the concept of bounded contexts in DDD.

The mistake most teams make is assuming that a single, unified model will scale across the entire system. It won’t. As complexity grows, the business itself fractures into distinct subdomains, each with its language, processes, and quirks. Trying to stretch one model across all of them leads to tangled abstractions, leaky assumptions, and endless edge cases.

Instead, DDD treats each subdomain as its bounded context:

In a payments context, an "Invoice" might be immutable and tied to tax rules.

In a customer support context, that same "Invoice" might be editable, cancellable, and used mostly for tracking communication history.

In a CRM context, "Customer" means a potential lead. In billing, it means someone who’s signed a contract.

Each of these models can (and should) evolve independently, as long as their integration points are clearly defined.

How to Spot a Bounded Context?

Bounded contexts often emerge naturally from:

Team boundaries: Different teams own different workflows or products.

Inconsistent definitions: The same term means different things in different places.

Integration friction: APIs that require translation layers or mapping logic.

Independent release cycles: Parts of the system change at different speeds.

The goal isn’t to slice the system into microservices. That’s an implementation detail. The real goal is to draw lines around specific meaning. For example, “within the context, these rules apply, and we don't let external assumptions leak in.”

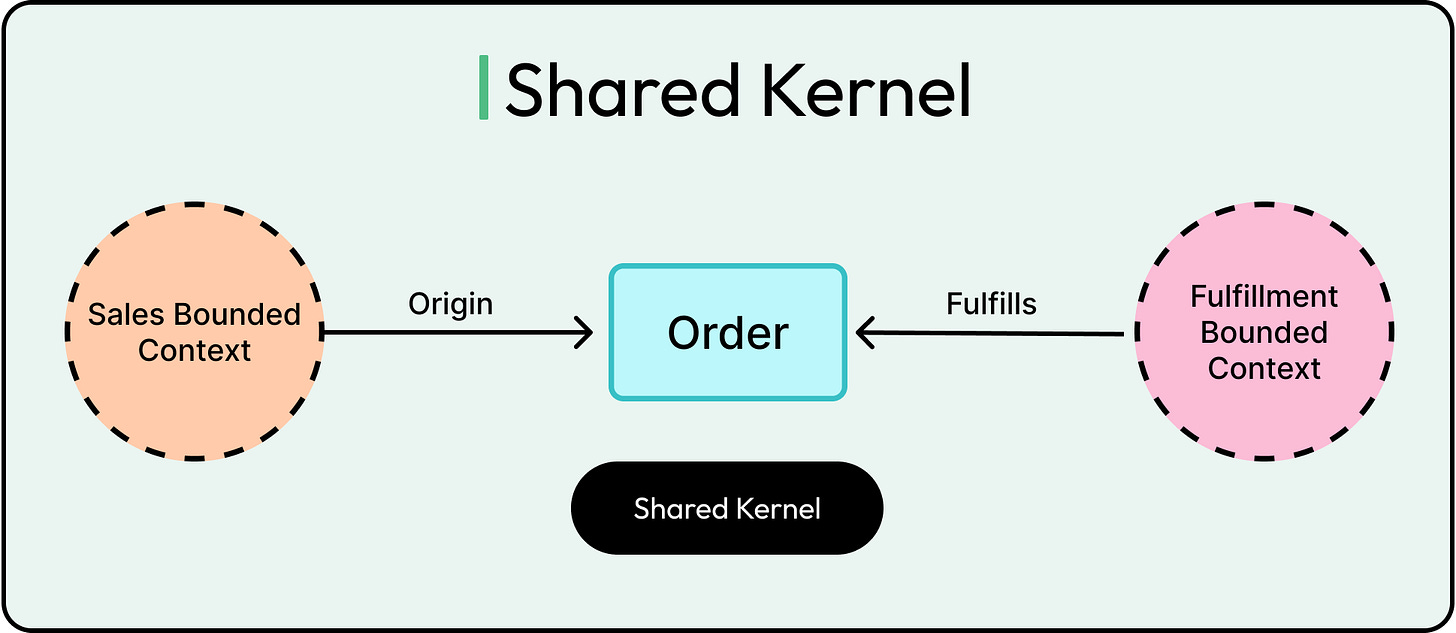

Context Maps

Once bounded contexts are identified, the next question is: how do they talk to each other?

Enter the Context Map. This is a high-level diagram or model that shows the relationships between contexts: how they integrate, which one depends on which, and what patterns govern those interactions.

Some common integration patterns are as follows:

Shared Kernel: Two contexts share a subset of the model explicitly.

Customer/Supplier: One context depends heavily on another's model, often upstream/downstream.

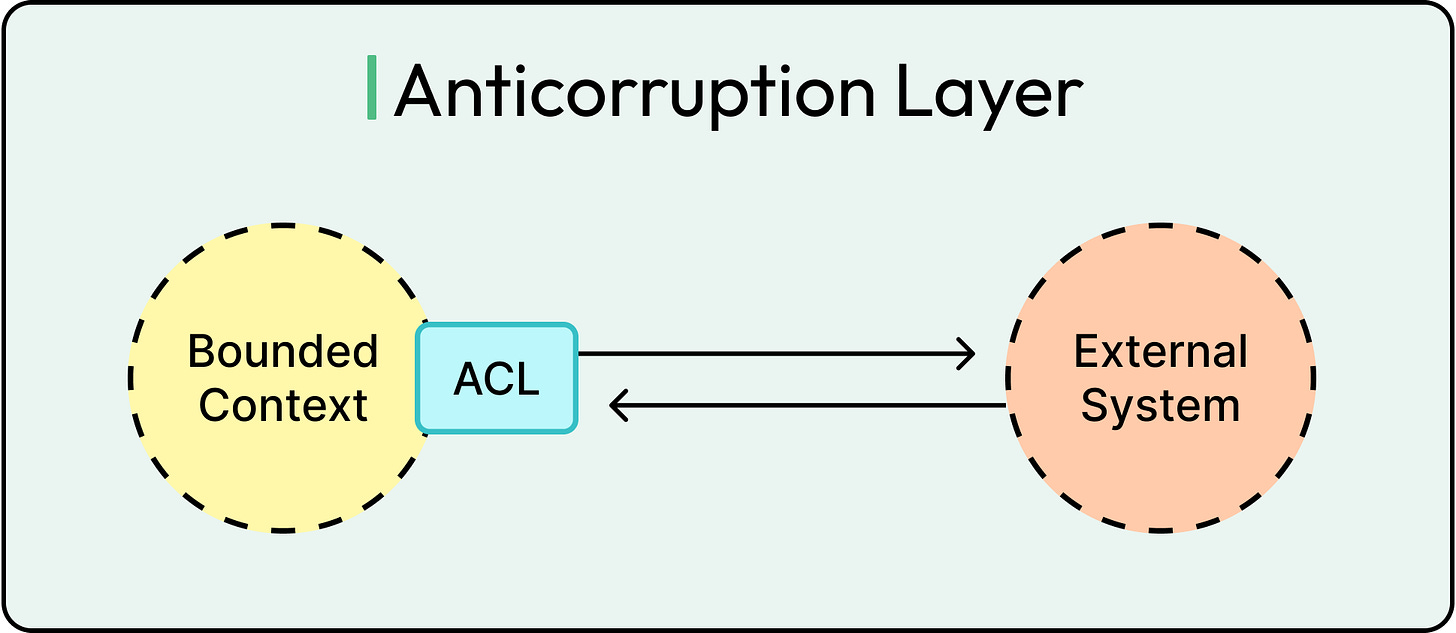

Anti-Corruption Layer (ACL): One context protects its model by translating data from another, preventing outside assumptions from contaminating its logic.

The relationships between bounded contexts help teams negotiate boundaries, define APIs, and prevent one model’s decisions from cascading through the whole system.

Ubiquitous Language

Code doesn’t live in a vacuum. It lives in meetings, whiteboards, Slack threads, and late-night production postmortems. And too often, the language in those places doesn’t match what’s in the code. The business talks about “clients,” the codebase refers to “users,” and the database table says “accounts.” Everyone nods along until a bug slips through because the system didn’t behave the way the business expected.

That gap is where confusion grows. And that’s exactly what Ubiquitous Language is designed to close.

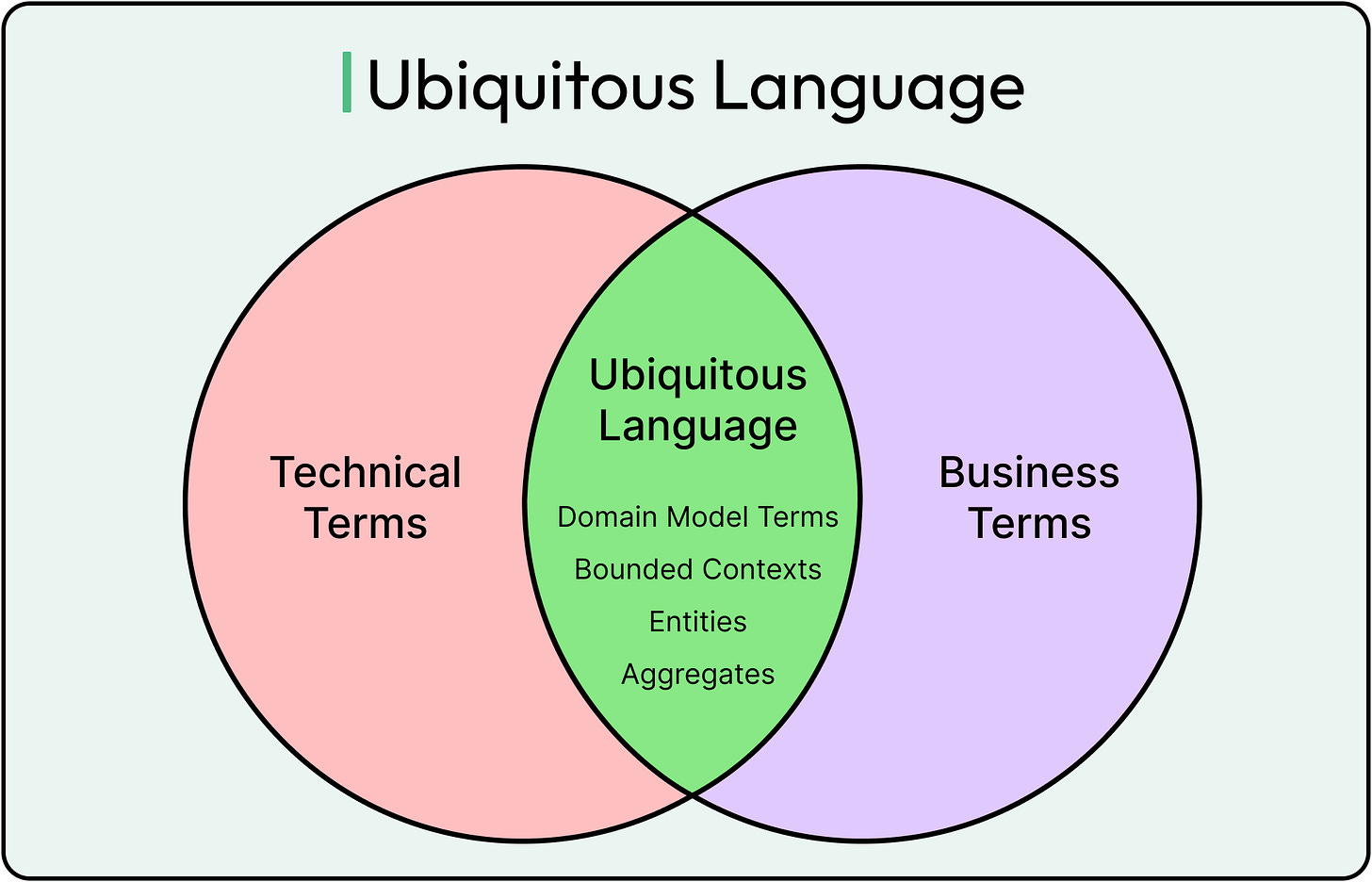

Ubiquitous Language means using a shared vocabulary across the team (consisting of domain experts, developers, testers, analysts) so that conversations about the system use the same terms as the code.

It’s not just naming variables better. It’s about creating a living language that reflects how the domain actually works, and then baking that language directly into the model.

When Ubiquitous Language shows up in code, it looks like:

Class names that match business concepts: Booking, Invoice, Shipment

Methods that reflect domain actions: cancel(), reschedule(), approve()

Events that describe business facts: OrderPlaced, InventoryDepleted, AccountSuspended

This language is the model, and it evolves alongside the domain. As the business discovers new rules, refines terminology, or discards outdated ideas, the language in the code should shift to match.

Why This Matters?

A consistent, shared language does more than make the codebase easier to read. It creates alignment between mental models:

Developers understand what the business actually means when it says “settle an invoice.”

Product managers can walk through code reviews and see terms they recognize.

New engineers ramp up faster because the domain model is transparent, not buried in technical abstraction.

When the language drifts (such as when “client” in the spec becomes CustomerDTO in the code, and “user” in the UI), it creates cracks in understanding. Those cracks widen over time, until developers don’t feel confident changing anything without fear of side effects.

This Isn’t Just About Naming

It’s tempting to treat ubiquitous language as a naming convention. However, it’s a collaborative process between developers and domain experts and involves asking questions like:

What’s the difference between a “draft order” and a “pending order”?

When does a “reservation” become a “booking”?

Is a “shipment” a container or the act of delivery?

Ubiquitous language fails when it’s imposed in a top-down manner and is inconsistent across contexts. Language evolves, and it’s a mistake to treat ubiquitous language as static.

Aggregates

It’s tempting to treat a domain model like a relational schema where everything is linked to everything else. However, in real systems, that approach breaks down fast. Change one thing, and ten others break. Load one entity, and the system tries to hydrate several related objects. Transactions get bloated, consistency gets fragile, and performance takes a nosedive.

Aggregates fix that, not by eliminating relationships, but by containing them.

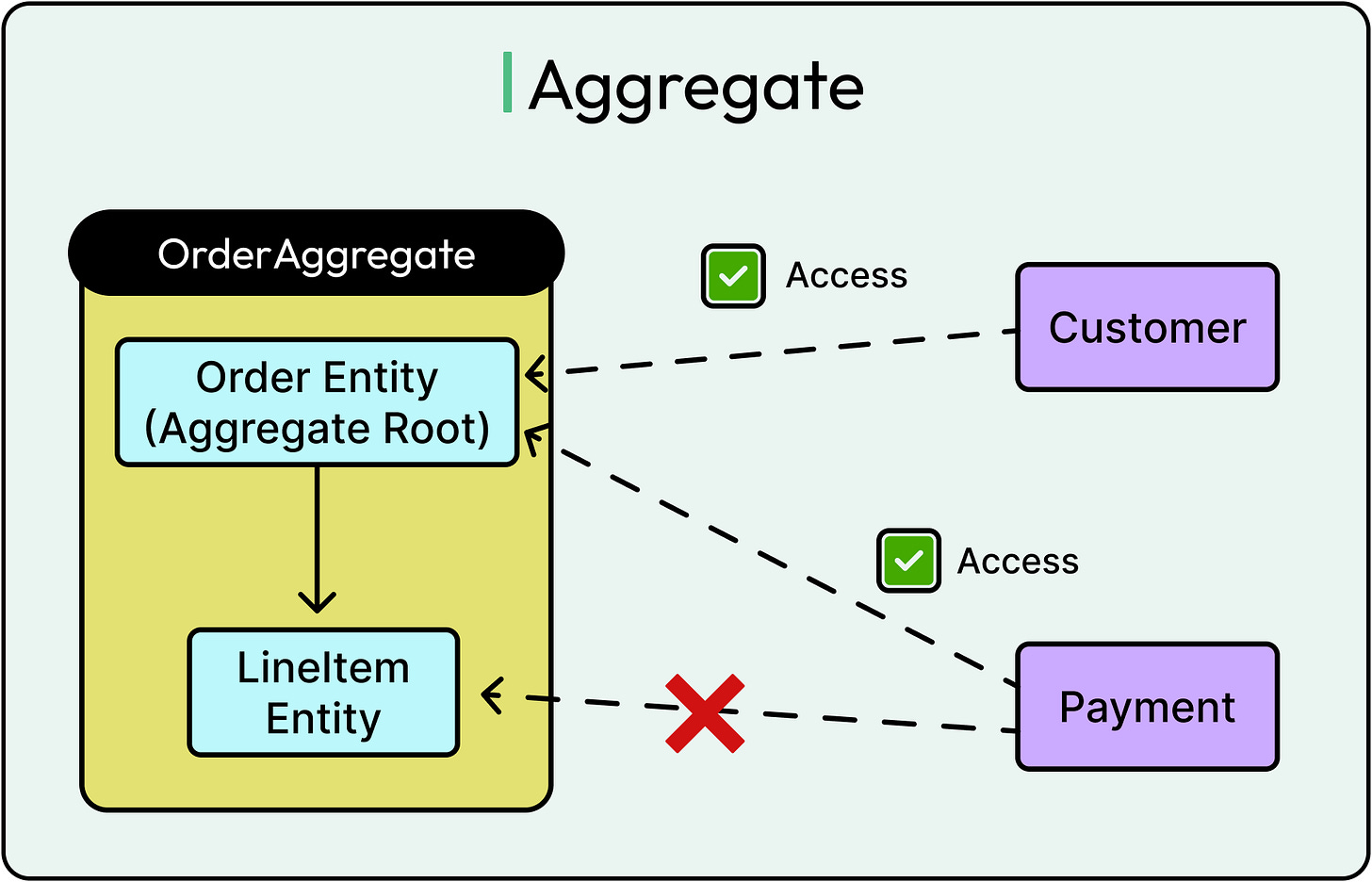

An Aggregate is a consistency boundary inside a bounded context. It’s a cluster of related domain objects that are treated as a single unit when making changes. Each Aggregate has one root entity, and all modifications flow through it. Anything outside the Aggregate can only reference it by the root’s identifier.

Why Aggregates Matter?

Aggregates give developers a way to:

Protect invariants: Rules like “a booking can’t be confirmed without payment” or “an order total must match its line items” live safely within the Aggregate, enforced transactionally.

Control transactions: Only the root handles commands that mutate state. That keeps the transaction scope tight and avoids inconsistent partial updates.

Simplify reasoning: With well-designed Aggregates, it’s possible to look at a single unit and understand what’s allowed, what’s not, and what side effects will occur.

Take an e-commerce domain:

An Order Aggregate might contain LineItems, ShippingDetails, and BillingInfo.

The Order is the root. No other service or class is allowed to directly manipulate LineItems. They have to go through Order.addItem() or Order.removeItem().

If the business rule is “an order cannot be shipped until it’s paid,” that logic belongs inside the Order Aggregate, not scattered across services or UI layers.

See the diagram below for an example of Aggregate:

Trade-offs and Design Pressure

Aggregates work best when they are small, focused, and autonomous.

But it’s easy to over-model and create massive Aggregates that try to represent everything. That leads to a few problems:

Lock contention in databases occurs when too many updates happen inside one big transactional boundary.

Slower performance when an Aggregate takes too long to load or save.

Tight coupling between unrelated concepts that happen to be connected.

Instead, model Aggregates around consistency needs, not just relationships. If two entities don’t need to be updated in the same transaction to maintain business correctness, they probably belong in separate Aggregates.

Some helpful points to keep in mind are as follows:

Design Aggregates so they can be loaded and saved quickly.

Keep invariants inside the Aggregate boundary.

Use domain events to communicate between Aggregates when eventual consistency is acceptable.

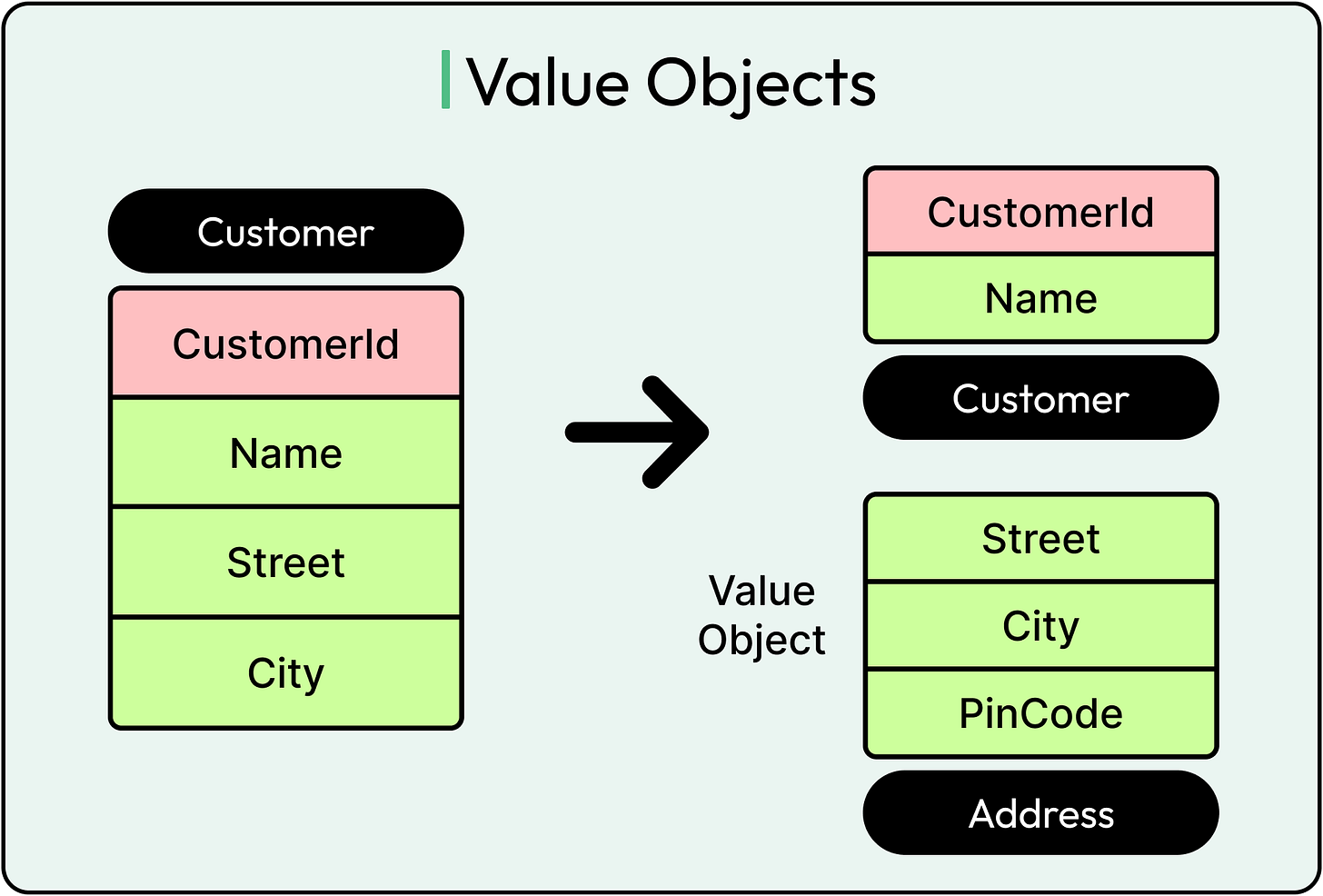

Entities and Value Objects

Not everything in a system deserves an identity.

Some things need to be tracked across time: orders, users, shipments. Others are meaningful only because of their properties: an address, a monetary amount, a date range. Confusing the two leads to models that are bloated, fragile, and harder to reason about than they should be.

DDD draws a clean line here: Entities have identity. Value Objects have meaning.

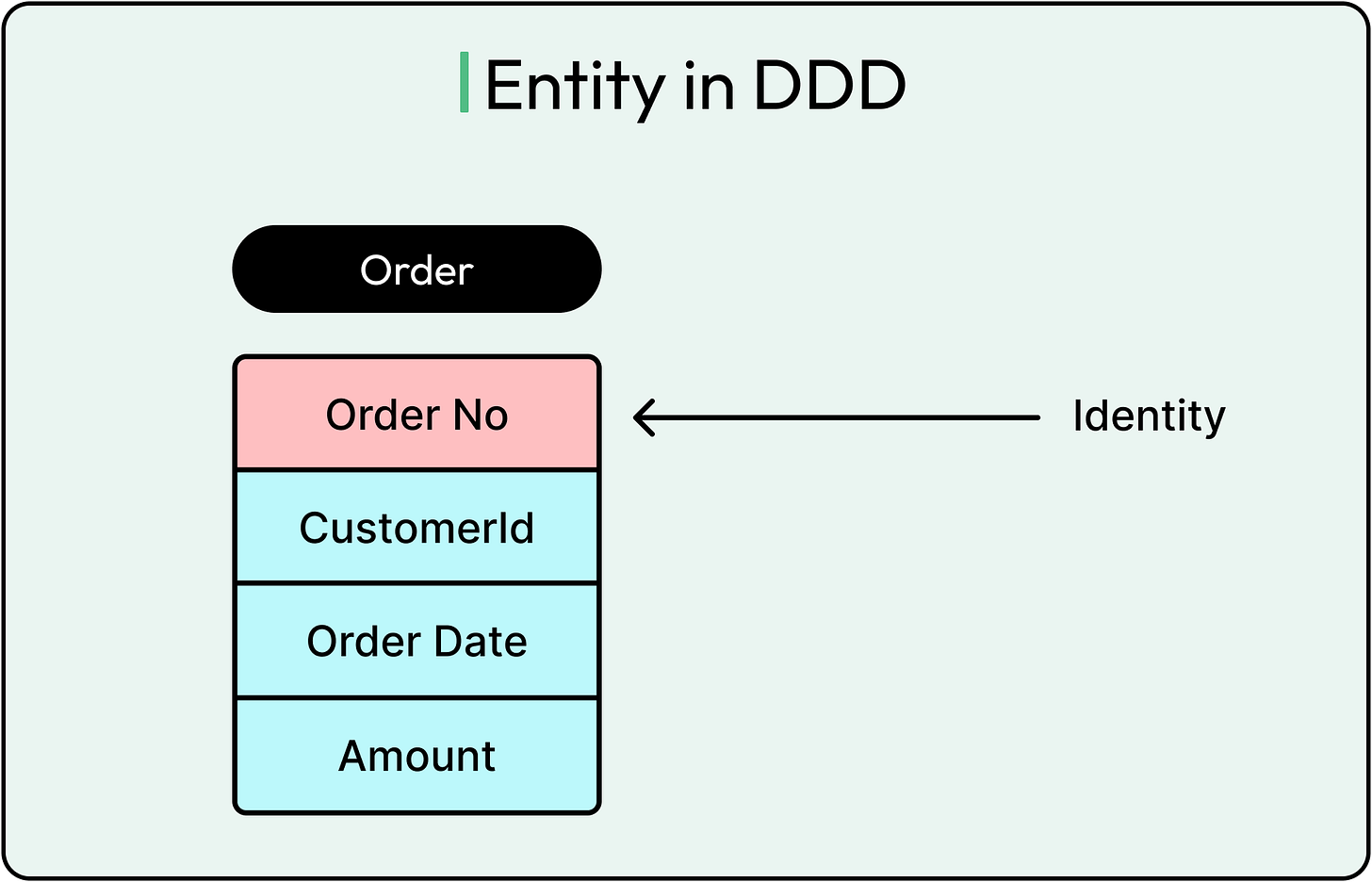

Entities: Things That Persist and Evolve

An Entity is anything that needs a consistent identity over time, even if its attributes change. A User might change their email, update their password, or move across countries. But it’s still the same user. The identity, often represented by a unique ID or primary key, is what matters.

Some defining characteristics of entities are as follows:

They have lifecycles and they get created, updated, archived, and deleted.

They are often referenced elsewhere in the system.

May contain other objects (including Value Objects), but acts as the gatekeeper for changes.

In real-world systems, Entities typically include:

Concepts like Customer, Order, Invoice, Product

Any object that needs to be audited, tracked, or referenced across contexts

The key trait of entities is persistence of identity, not just persistence in storage.

Value Objects: Defined by Their Attributes

A Value Object, on the other hand, is immutable and disposable. It’s meaningful because of what it is, not who it is. A Money object with amount and currency is a perfect example. If two Money(100, USD) objects exist, they’re effectively the same. There’s no reason to track them separately.

Some defining characteristics of Value Objects are as follows:

They are immutable. Once created, they never change.

Have no unique identity. Two instances with the same values are interchangeable.

Can be freely created, copied, or discarded.

Works well for modeling measurements, coordinates, settings, or concepts like DateRange, Address, Email, or PhoneNumber.

Immutability isn't just a purity thing. It prevents accidental mutation and simplifies debugging. There’s no "what state was this in yesterday" with a Value Object. It either exists in the current shape, or it doesn’t.

Common Pitfalls

Getting this distinction between entities and value objects right makes models leaner, more expressive, and easier to maintain. Some common pitfalls are as follows:

Over-identification: Giving everything an ID "just in case" leads to object inflation and broken encapsulation.

Shared mutable Value Objects: Passing a mutable Address around multiple Aggregates almost guarantees future data integrity issues.

Entity bloat: Putting every related concept into one Entity, instead of modeling Values cleanly, leads to giant objects that are hard to test and reason about.

Domain Events

Most systems don’t fail because a service went down. They fail because something important happened and nobody noticed. Here are a few examples:

A customer made a purchase, but the shipping service wasn’t updated.

A payment failed, but the order stayed in limbo.

A user upgraded their plan, but the feature flags didn’t flip.

These aren’t infrastructure failures. They’re coordination failures. The domain changed, and the rest of the system doesn’t know about it.

This is what Domain Events solve.

A Domain Event captures a meaningful business occurrence, something that already happened, in the past tense, and matters to other parts of the system. It’s not a command, it’s not a notification, and it’s not about infrastructure. It’s about documenting facts that emerge from domain behavior.

Domain Events give systems a way to react without coupling. Instead of hardcoding service A to call service B when something happens, emit an event: “OrderPlaced.” Now, any service that cares about this event (such as billing, inventory, marketing) can subscribe and take action based on their business rules.

What Makes a Domain Event?

Not every event is a Domain Event. A log line like “Retrying connection to Redis” or “Email queued” doesn’t qualify. A real Domain Event should:

Reflect a business-level change: For example, PaymentReceived, ShipmentDelayed, UserVerified.

Be named in the past tense: it already happened, and the system can’t undo it.

Be raised by the domain model, not by infrastructure or glue code.

Often results from a state change in an Aggregate.

These events live inside the model, not at the edge of the system. They emerge naturally from behaviors: placing an order, canceling a reservation, or confirming a booking.

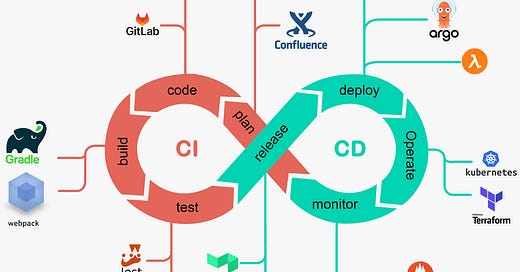

Designing for Change

Domain Events make it easier to extend functionality without touching existing code.

Let’s say we want to trigger a follow-up email when a user completes onboarding. There is no need to make a change to the registration service. Just subscribe to the UserOnboarded event.

But there are trade-offs:

Order and timing aren't guaranteed in distributed systems.

Failures in consumers shouldn’t affect the producer. Resilience patterns are essential.

Schema evolution must be managed carefully. Once events are in the wild, changing their shape becomes risky.

Repositories

Every domain model needs data to do anything useful. But it also needs protection from ORMs, from databases, from HTTP layers, and from anything else that doesn’t belong in core business logic. Without that protection, the model gets polluted. Entities start carrying annotations from persistence libraries. Value Objects get shaped to match table schemas. Aggregates leak getters and setters just to satisfy some repository API.

Repositories exist to prevent that.

A Repository provides a collection-like interface to Aggregate Roots, abstracting how they’re loaded, saved, and queried. It’s not just about CRUD. It’s about keeping the domain model clean and free from infrastructure concerns, so it can evolve based on business needs, not database limitations.

In plain terms, the domain says, “I need this Order to apply a discount.” The Repository’s job is to deliver that Order Aggregate in a way that lets the domain do its work, without exposing how the data got there.

Repositories should:

Only operate on Aggregate Roots. Never return partial trees or internal entities.

Reflect Ubiquitous Language. Use domain terms for queries, not technical jargon.

Shield the domain from persistence details. The domain layer shouldn’t know if it’s backed by SQL, Mongo, or an API call.

What Repositories Are Not?

Here are a few points to keep in mind about repositories:

They’re not generic “data access layers.” A GenericRepository<T> sounds DRY, but it erases domain meaning and encourages CRUD thinking.

They’re not infrastructure dumping grounds. Cramming query builders, caching, and retry logic into the same class turns Repositories into god objects.

They’re not services. They don’t orchestrate use cases. They supply Aggregates so that use cases can run business logic.

Repositories work well when they are thin, focused, and language-aligned. But they can get messy when:

The Aggregate is too large and slow to load.

The persistence model diverges from the domain model.

Query requirements become complex and don’t fit neatly into Aggregate access patterns.

In those cases, it’s better to introduce query-side models for reporting and keep Repositories dedicated to use-case execution.

When and When Not to Use DDD?

DDD isn’t a default setting. It’s not the architectural equivalent of "use version control" or "write unit tests." It’s a powerful approach that solves a specific kind of problem, and when those problems aren’t present, DDD can turn into overdesign.

The trick isn’t deciding whether DDD is good. The trick is knowing when it’s necessary and when it’s not.

Domain-Driven Design pays off when the domain has depth, ambiguity, and change:

Depth: The business logic is layered, nuanced, and can't be captured with simple CRUD operations. Think configurable pricing engines, policy evaluations, or claims processing.

Ambiguity: Different parts of the system define the same concepts differently. Sales and support talk about "customer" in different ways. Finance and operations don’t agree on what "cancel" means. DDD brings clarity through bounded contexts and ubiquitous language.

Change: The business rules evolve frequently. New features, edge cases, regulations, or product pivots require the model to adapt without crumbling.

Not every system needs this level of modeling rigor. Some domains are simple and stay simple. For example:

A content management UI with basic user roles and document uploads.

An internal admin dashboard backed by a single CRUD-style database.

A data ingestion pipeline with minimal business rules.

A one-off automation tool built around external API calls.

In these cases, adding aggregates, domain events, and context maps can feel like overkill. The model gets heavier, not clearer. Teams spend more time designing abstractions than shipping features.

Common Pitfalls with DDD

DDD looks deceptively elegant on paper. Bounded contexts, ubiquitous language, and aggregates make sense in a workshop or when diagrammed on a whiteboard. But once real deadlines, legacy constraints, and team dynamics come into play, things often go sideways.

Not because DDD is flawed, but because it’s easy to misapply the principles without fully understanding the trade-offs. Here’s where things usually break.

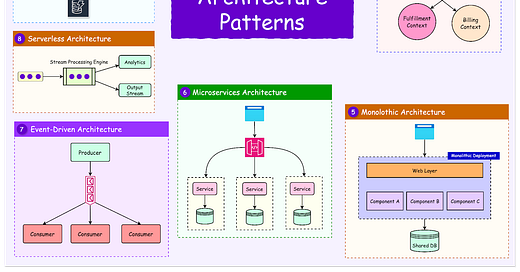

1 - Treating DDD Like an Architecture Pattern

DDD is not a layered architecture. It’s not a microservices template. It’s a modeling discipline, a way to reason about complexity in systems where business rules are critical. But teams often reach for DDD like it’s a new design pattern. That leads to models packed with terminology, but no real meaning.

Some symptoms for this behavior are as follows:

“We created aggregates for everything” (even when no business invariants existed).

“We split into microservices because DDD says Bounded Contexts = microservices.”

“We implemented event sourcing and CQRS because it’s part of DDD, right?”

DDD doesn’t prescribe infrastructure. It starts with understanding the domain deeply. Everything else flows from that.

2 - Overengineering in Simple Domains

Not every application needs aggregates, value objects, or even entities. If a feature is CRUD with no domain rules, DDD might be overkill.

The trap is that teams apply DDD wholesale across the codebase, instead of focusing efforts on the parts of the system that carry complexity. This results in slower delivery, frustrated developers, and a bloated model that explains nothing better than a simple script would have.

3 - Misunderstanding Bounded Contexts

The term sounds architectural, but it’s conceptual. Bounded Contexts are about semantic boundaries, not technical layers. Teams often confuse them with microservices, modules, or even deployment units.

A Bounded Context doesn’t mean “split this code into a new repo.” It means: within this boundary, terms, models, and rules are consistent. Outside of it, they’re not.

4 - Forgetting Ubiquitous Language

DDD loses its impact when teams stop evolving the language. If engineers use different terms than the business, or the model drifts into generic abstractions (DataModel, Manager, Handler), then the heart of DDD is already gone.

A healthy Ubiquitous Language lives in:

Class and method names

Diagrams and discussions

Pull requests and tests

Product specs and conversations with domain experts

When language stops reflecting reality, the model stops reflecting the domain.

5 - Ignoring the Domain

This might sound obvious, but it’s common: teams say they’re doing DDD while barely engaging with the domain.

Some symptoms of this behavior are:

No involvement from business stakeholders or subject matter experts

Domain rules are encoded in spreadsheets, not in code

Developers building models based on assumptions or technical guesswork

Without real collaboration, the "domain model" gets disconnected from how the business works.

6 - Using Events to Bypass Design

Domain Events are powerful, but they’re not a license to skip modeling. Firing off dozens of events from everywhere in the system without understanding what’s happening leads to chaos, not clarity.

Events should emerge from well-modeled behavior. They should reflect facts that matter to the domain, not just system noise or glue logic.

7 - Building “DDD Frameworks”

Trying to abstract DDD into a reusable “domain engine” or general-purpose framework usually backfires. DDD isn’t about generic tooling. It’s about tailoring models to a specific domain.

The moment things get abstracted too far, the domain gets blurry and the rules lose their sharp edges.

DDD and Microservices: Related But Not the Same Thing

At some point during the last few years, DDD got swept up in the microservices hype cycle. It’s easy to see why. Both promote modularity, autonomy, and clear boundaries. But treating them as the same thing creates more confusion than clarity. DDD is not about microservices. And microservices don't require DDD to be effective.

What DDD brings to the table is semantic structure. Microservices bring deployment independence. They're orthogonal concerns.

One deals with what the system means. The other deals with how the system runs. Conflating them leads to bad outcomes: tiny services with meaningless models, oversized aggregates stuffed into REST endpoints, and teams who split their codebase into multiple repos before defining a single bounded context.

DDD Can Inform Microservices Boundaries

When done well, DDD provides the map for microservice design. Bounded Contexts can define the edges of services. Ubiquitous Language ensures the model inside each service aligns with the domain it supports. Context Maps can describe integration patterns: how services talk, who depends on whom, and how teams collaborate or stay isolated.

But notice the order: DDD first, microservices second. Otherwise, the architecture outruns the model.

Startups and growing teams often benefit from using DDD inside a modular monolith: multiple bounded contexts in one deployable unit. That allows fast development while still maintaining clean separation. If and when operational scale demands it, those contexts can split out into services along the same lines.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at Domain Driven Design in detail, along with its role in modern system design and architecture.

Some key learning points are as follows:

Most systems fail not because of bad code, but because the software drifts away from what the business needs. DDD keeps them aligned.

DDD is a way to model software around domain logic through collaboration and language, not just technical abstraction.

Bounded Contexts define where a domain model applies, preventing semantic confusion and isolating complexity.

Ubiquitous Language ensures that everyone speaks the same language in code and conversation, reducing miscommunication and errors.

Aggregates protect business invariants by grouping domain objects under a single root and defining clear consistency boundaries.

Entities model identity over time, while Value Objects represent concepts through structure and immutability. Knowing the difference keeps the model clean.

Domain Events capture meaningful business facts, enabling decoupled systems to react without tight integration.

Repositories abstract data access for Aggregates, keeping persistence concerns out of the domain model.

DDD thrives in domains with rich, evolving rules like finance, logistics, and multi-team SaaS platforms.

DDD is overkill for simple, static systems. Use it when the domain complexity justifies the modeling effort.

Common pitfalls include overengineering, misusing terminology, skipping domain collaboration, and applying DDD as a technical checklist.

DDD and microservices are not the same. Use DDD to define meaningful boundaries, then decide if services should follow.

Great article.

Briefly and succinctly describes the main aspects of the methodology. "Bounded context - ... It's a semantic boundary ..." - there are few places where you will find mention of this aspect by the authors, and even less often, the understanding of this aspect by the developers.

We express our understanding of various things in terms (words). Sometimes, the same terms can have a similar (but not identical) meaning. Bounded context is a cornerstone in DDD that allows us to separate flies from cutlets.

Thanks for this article!