A system's usefulness depends heavily on its ability to communicate with other systems.

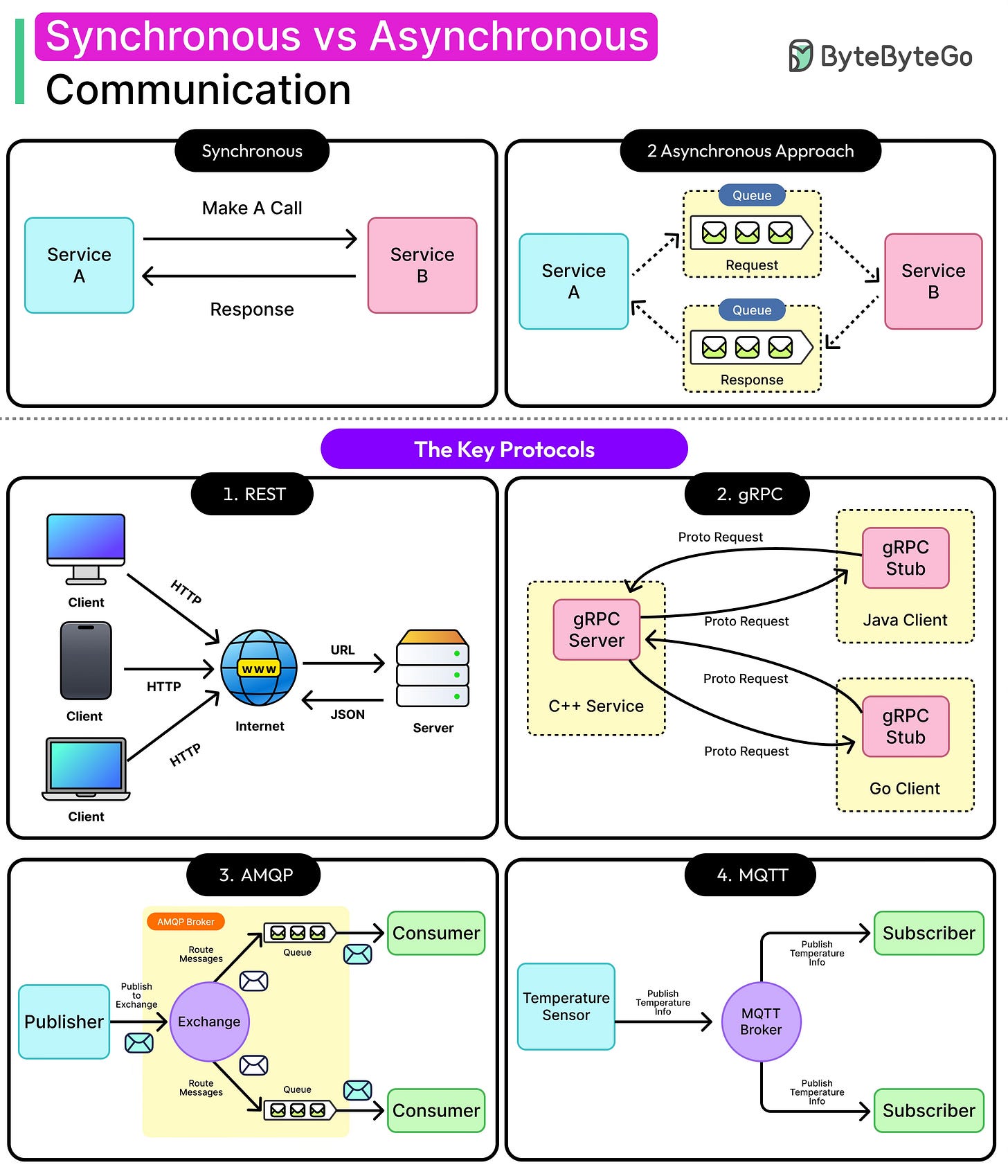

That’s true whether it’s a pair of microservices exchanging user data, a mobile app fetching catalog details, or a distributed pipeline pushing events through a queue. At some point, every system has to make a call: Should this interaction happen synchronously or asynchronously?

That question surfaces everywhere: sometimes explicitly in design documents, sometimes buried in architectural decisions that later appear as latency issues, cascading failures, or observability blind spots. It affects how APIs are designed, how systems scale, and how gracefully they degrade when things break.

Synchronous communication feels familiar. One service calls another, waits for a response, and moves on. It’s clean, predictable, and easy to trace. However, when the service being called slows down or fails, then everything that depends on it also gets impacted.

Asynchronous communication decouples these dependencies. A message is published, a job is queued, or an event is fired, and the sender moves on. It trades immediacy for flexibility. The system becomes more elastic, but harder to debug, reason about, and control.

Neither approach is objectively better. They serve different needs, and choosing between them (or deciding how to combine them) is a matter of understanding different trade-offs:

Latency versus throughput

Simplicity versus resilience

Real-time response versus eventual progress

In this article, we’ll take a detailed look at synchronous and asynchronous communication, along with their trade-offs. We will also explore some popular communication protocols that make synchronous or asynchronous communication possible.

Understanding the Basics

Before diving into protocols and real-world use cases, let us step back and understand what synchronous and asynchronous communication mean.

Synchronous Communication

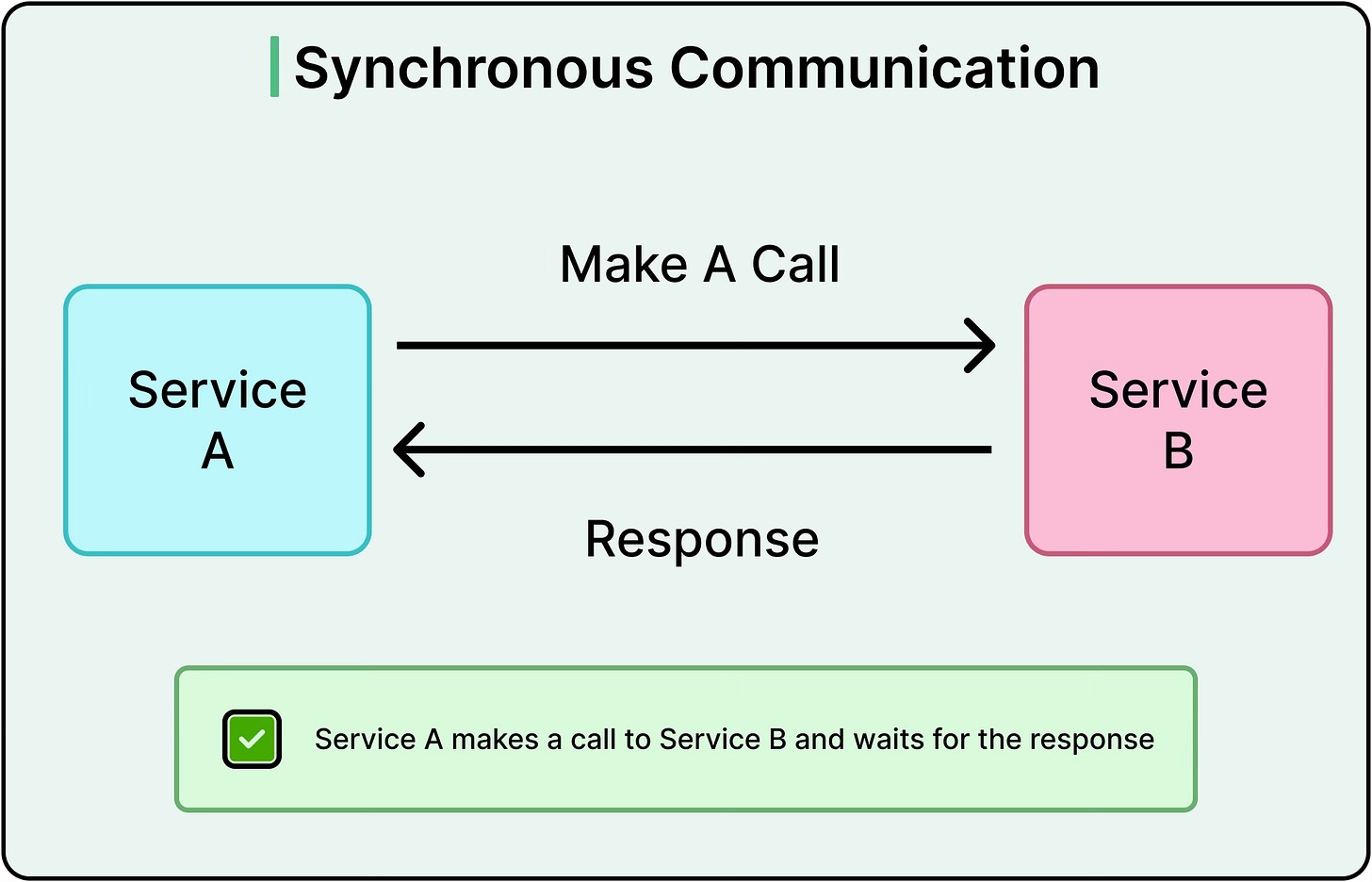

Synchronous communication follows a simple rule: ask, wait, then act. One component sends a request to another and stalls until a response arrives. It’s the architectural equivalent of a phone call where both parties need to be present, and the conversation can’t move forward until the other side replies.

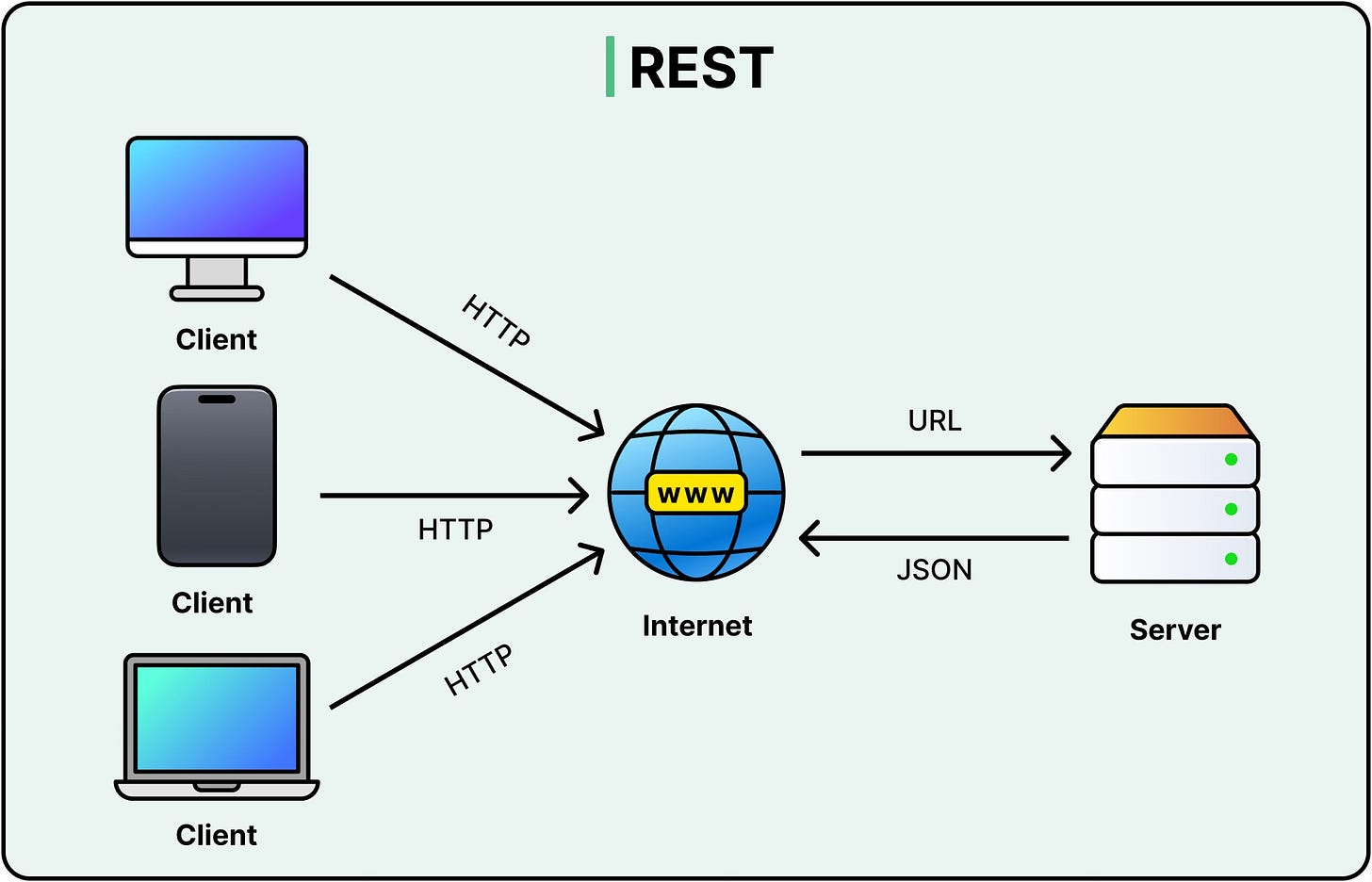

RESTful HTTP APIs are an example of this communication style. The same model applies in microservices: Service A calls Service B and halts until B responds with data or an error.

See the diagram below:

Synchronous communication feels natural because it reflects human expectations. It’s easy to reason about, test, and debug. There’s a direct line from cause to effect. If something breaks, stack traces usually point to the source.

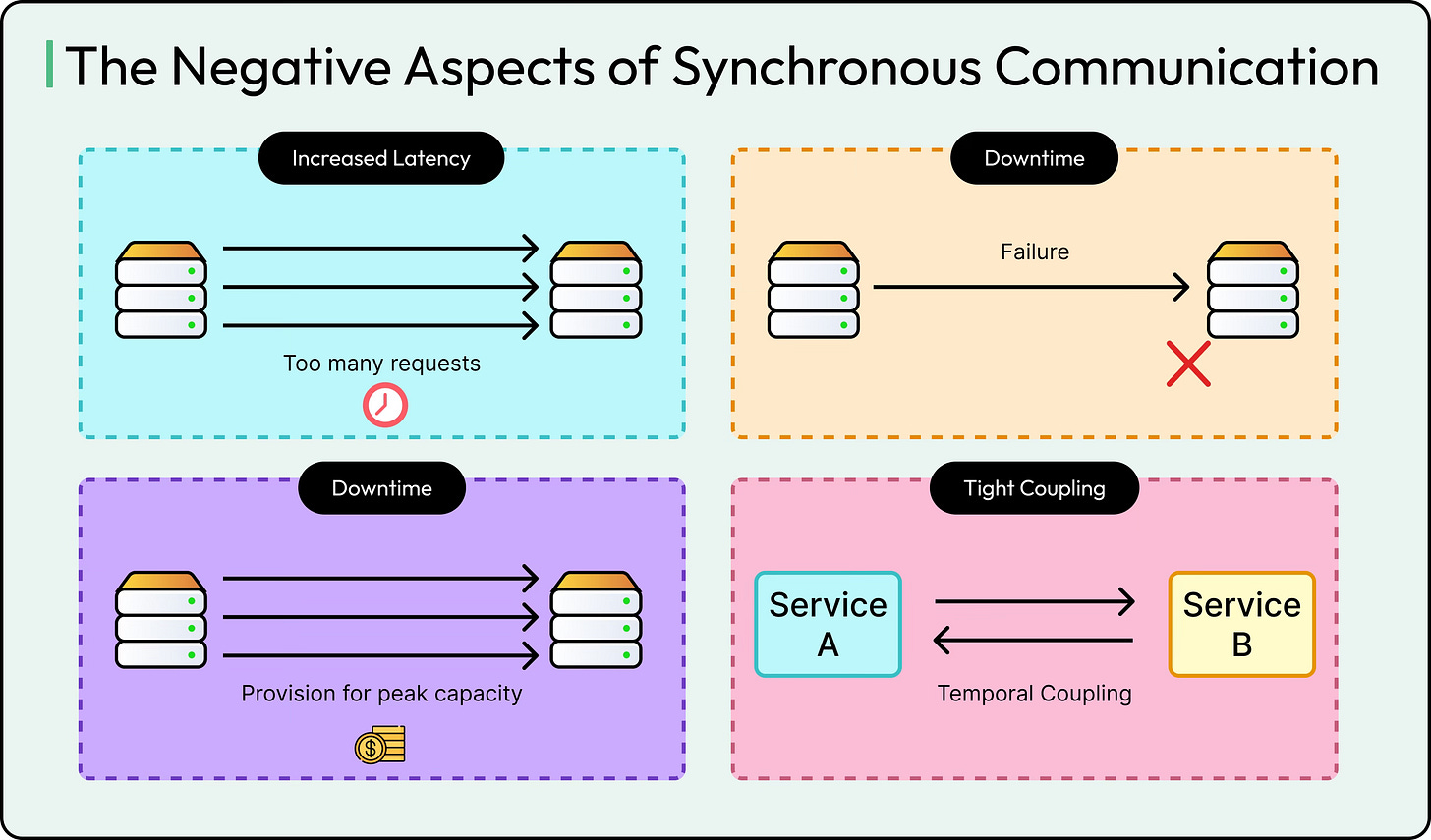

But that clarity comes at a cost:

If the downstream service is slow, the caller waits.

If the downstream service is down, the caller can also fail.

If too many requests pile up, latency increases across the system.

This coupling of availability, performance, and time means synchronous systems work best in environments with predictable latency, stable network paths, and tightly controlled dependencies. They start to perform poorly under high throughput or variable response times.

Asynchronous Communication

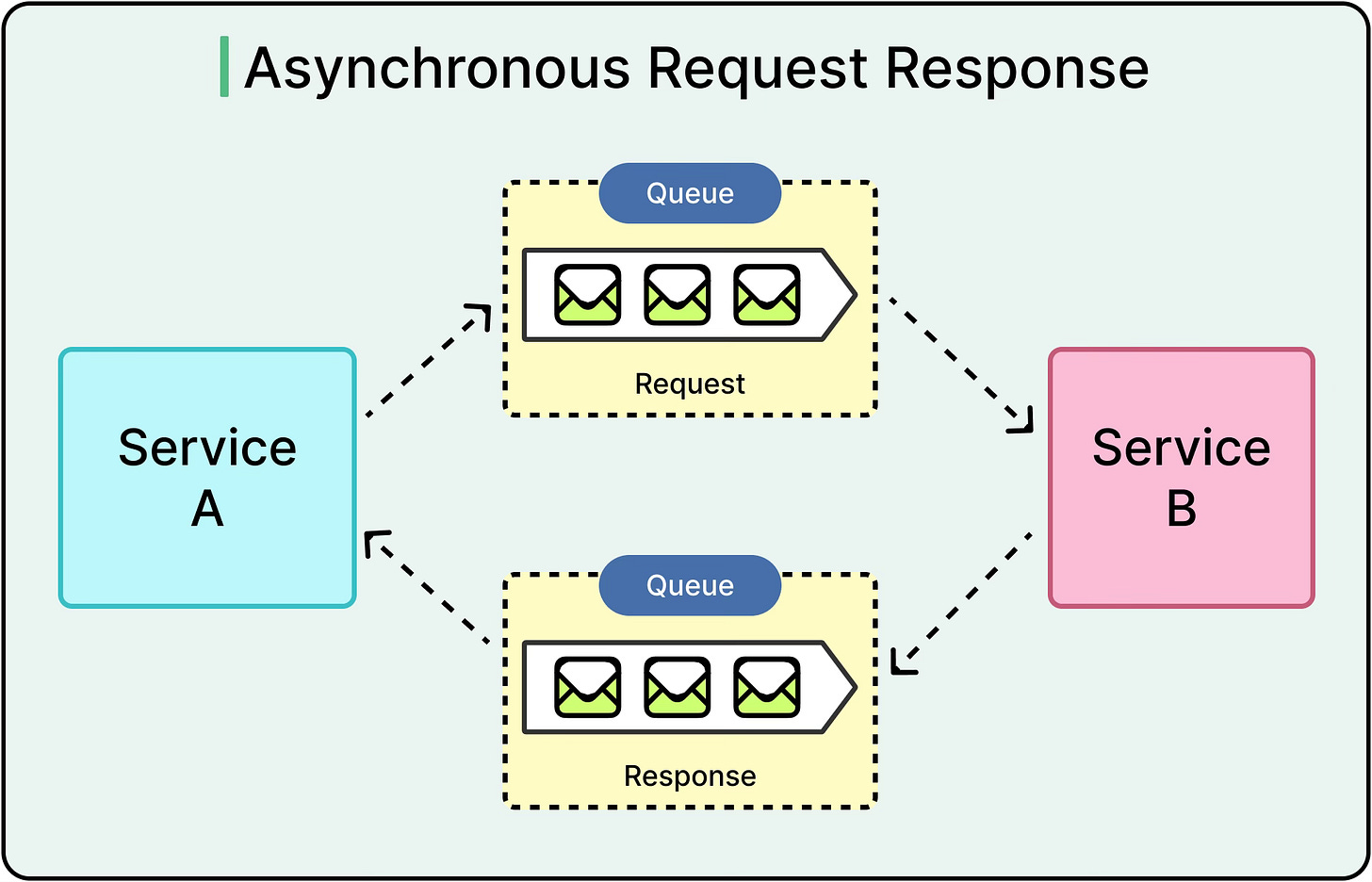

Asynchronous communication breaks the dependency on an immediate response. One component sends a message and moves on. Whether that message is a task, an event, or a signal, the sender doesn't block and can continue with other work.

This model shows up in message queues, publish-subscribe systems, and event-driven architectures. A service emits an event to a queue like RabbitMQ. Another service consumes it later, maybe in milliseconds or seconds. The sender doesn’t care.

Asynchronous systems prioritize decoupling by allowing services to operate independently in time. This way, they can absorb traffic bursts and continue processing even when downstream consumers are temporarily offline.

To make this work, asynchronous systems introduce patterns like:

Message queues buffer work across time boundaries.

Callbacks or event handlers, which resume logic when results arrive.

Outbox patterns to ensure reliable event publishing alongside database writes.

While this approach enables higher throughput, better fault tolerance, and greater flexibility, it shifts complexity elsewhere. Monitoring becomes harder, and errors may surface hours later, detached from the root cause.

Core Differences

At the heart of the synchronous vs. asynchronous distinction are three types of coupling: time, space, and reliability.

Time Coupling: Synchronous systems require both sender and receiver to be available at the same time. Async communication introduces a buffer (a queue, a broker, a topic) between them. This makes async models more tolerant of slow or offline components.

Space Coupling: In synchronous setups, the sender must know exactly where the receiver lives: its address, protocol, API. In asynchronous designs, a sender posts a message to a topic or queue. Multiple receivers may exist, or none at all. This flexibility supports dynamic scaling and loose coupling.

Reliability Handling: In synchronous systems, retries happen at the client side. If the server fails mid-request, the client needs to try again or handle the failure. Asynchronous systems shift that burden to the message broker, which handles redelivery, ordering, and retries. However, this adds layers of infrastructure and operational cost.

The trade-offs often come down to this:

Synchronous calls offer simplicity and immediacy, but suffer under latency and tight coupling.

Asynchronous models enable scalability and resilience, but introduce operational complexity and delayed feedback.

Ultimately, there’s no universal answer on choosing one over the other. The right model depends on what matters more: getting a response now or making progress eventually. Systems often mix both, carefully choosing where to block and where to defer.

Protocol Deep Dive: Comparing the Communication Models

Choosing between synchronous and asynchronous communication is only part of the story.

The next layer is protocol design: how information gets transferred between systems, how efficiently, how reliably, and under what constraints. Each protocol carries assumptions about usage, delivery guarantees, and system design.

Understanding those assumptions is key to making the right architectural decisions. Let’s look at some of the most popular protocols.

1 - HTTP/REST

HTTP remains the most widely used protocol in distributed systems, and for good reason. It’s simple, ubiquitous, and well-supported across every language, framework, and platform.

RESTful APIs, built on HTTP, have become the default choice for synchronous service interactions.

HTTP follows a stateless, request-response model. One party makes a request, usually over a URI like GET /users/123, and waits for a response. Each interaction is self-contained. There’s no memory of past exchanges unless the client or server explicitly maintains session state.

This model works well for:

CRUD operations on resources.

Frontend-to-backend API calls.

Internal microservice APIs where latency is tolerable.

The simplicity of HTTP makes debugging, caching, and tracing relatively straightforward. But its blocking nature introduces limits. While a service waits for a response, it ties up compute resources (threads, connections, memory). That idle time adds up under heavy load.

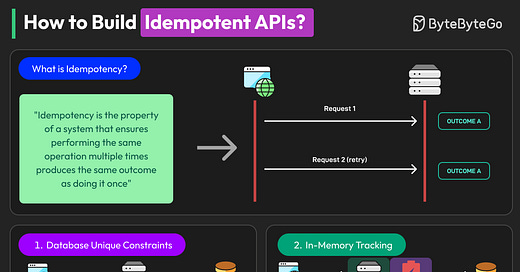

HTTP retries also come with caveats. When a network error or timeout occurs, a retry might duplicate an operation unless the API is designed to be idempotent: a non-trivial requirement for write-heavy endpoints.

HTTP works best when:

Low latency is expected

Both parties are online and available

The interaction needs a clear, immediate response

However, it starts to struggle in workflows where latency spikes, partial availability, or background processing are the norm.

2 - WebSocket

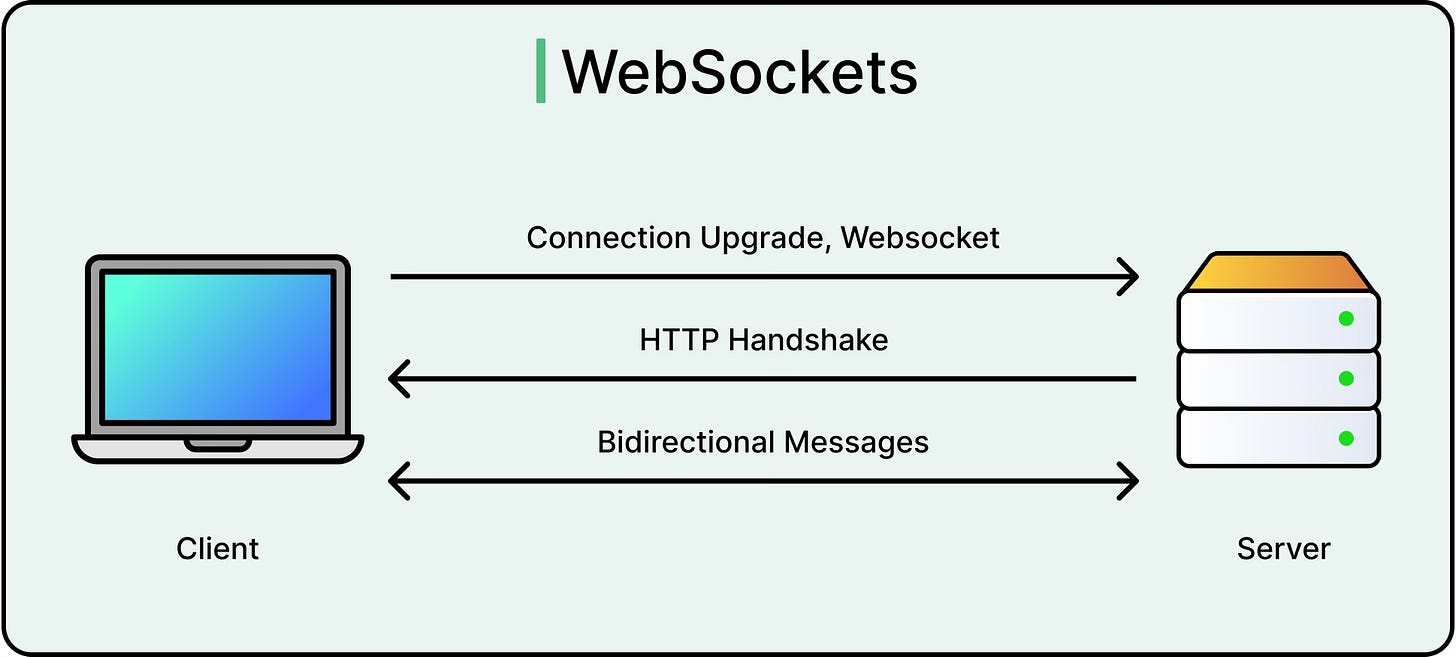

WebSocket fills a gap that HTTP can’t easily address: real-time, two-way communication over a single, long-lived connection. Unlike HTTP, where the client initiates every request, WebSocket allows both client and server to send messages at any time.

A WebSocket connection begins with an HTTP handshake and then upgrades to a persistent TCP connection. From that point on, either side can push data as needed. There’s no need to poll, reconnect, or renegotiate headers.

This makes WebSocket ideal for:

Live chat applications

Multiplayer games

Stock ticker dashboards

Collaborative tools (for example, shared whiteboards or Google Docs-style editors)

Although WebSocket technically operates asynchronously because messages are pushed whenever ready, it often feels synchronous from a user experience perspective. Messages go out, responses come in, and interactions feel instantaneous.

However, WebSocket introduces its trade-offs:

Connection state must be managed explicitly

Load balancers need special handling for long-lived connections

Message delivery is not guaranteed unless implemented at the application layer

WebSocket works well when:

Real-time updates matter more than request/response clarity

Latency must stay low and consistent

Both endpoints remain online during interaction

It's less suited for disconnected clients, mobile networks, or scenarios that require guaranteed delivery or durable queues.

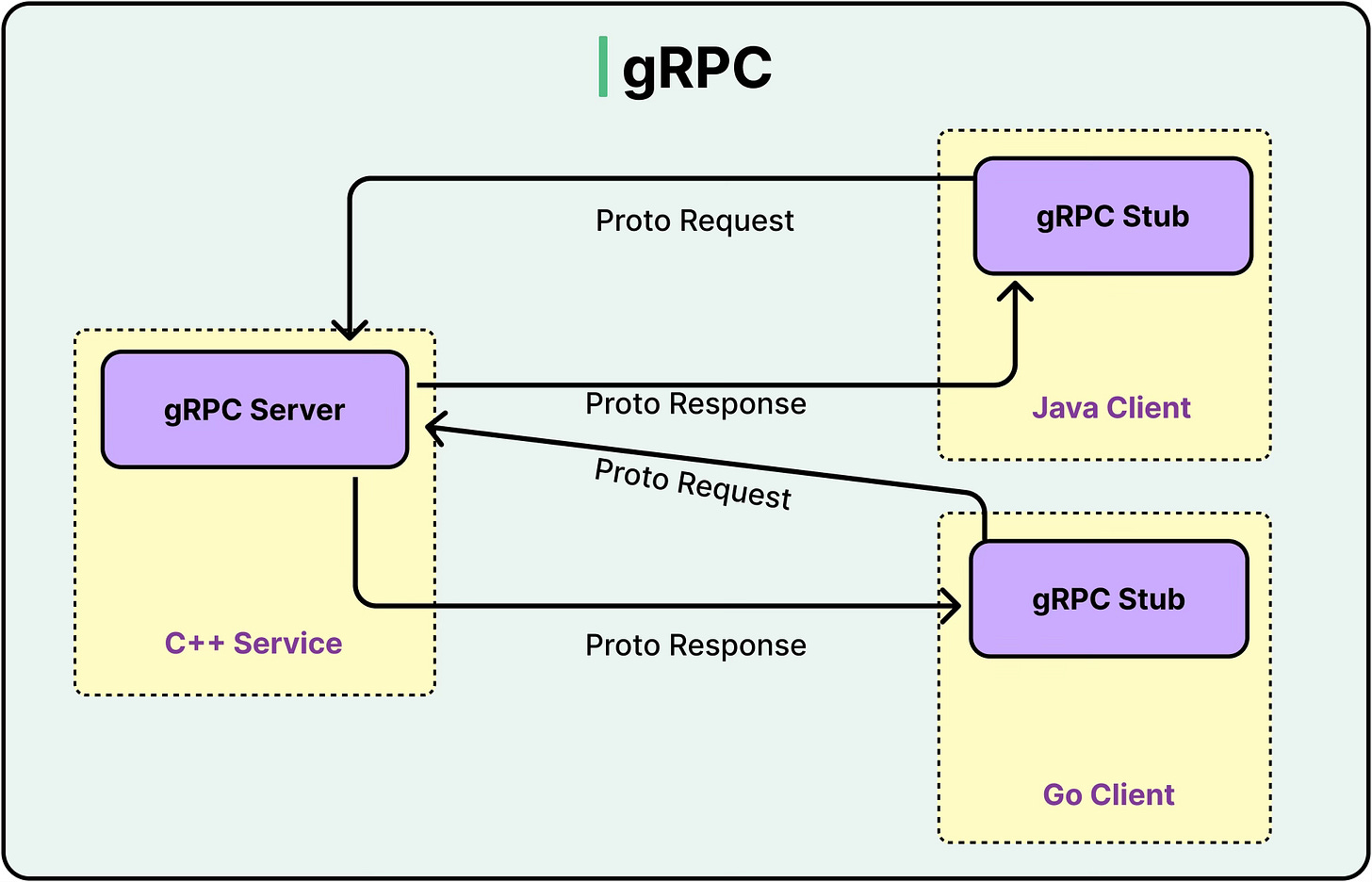

3 - gRPC

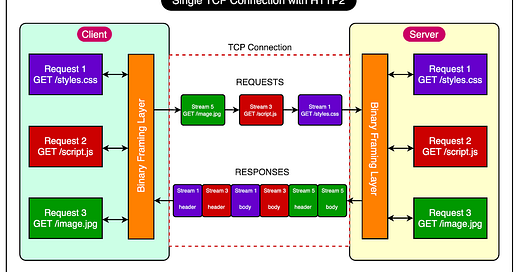

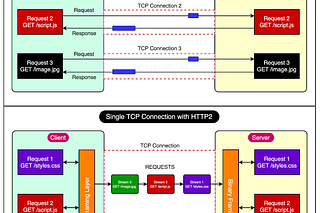

gRPC is a modern protocol designed for high-performance communication between distributed systems. It runs on top of HTTP/2 and uses Protocol Buffers (Protobuf) for message serialization, which makes it compact and fast.

At its core, gRPC enables Remote Procedure Calls (RPCs). One service can directly invoke a method on another service, as if it were calling a local function. Underneath, gRPC handles serialization, transport, and connection pooling.

Some key features of gRPC are as follows:

Strong typing with Protobuf definitions

Streaming support, including client-streaming, server-streaming, and bidirectional streaming

Built-in support for deadlines, retries, and metadata

gRPC is well-suited for:

High-throughput microservice meshes

Multi-language environments (for example, Python client calling a Go backend)

Internal APIs where bandwidth and performance matter

Unlike REST over HTTP/1.1, which creates a new TCP connection for each request, gRPC multiplexes many calls over a single connection using HTTP/2 streams. This improves efficiency and reduces latency.

gRPC balances the familiarity of synchronous request-response models with modern performance needs. But it also comes with a learning curve.

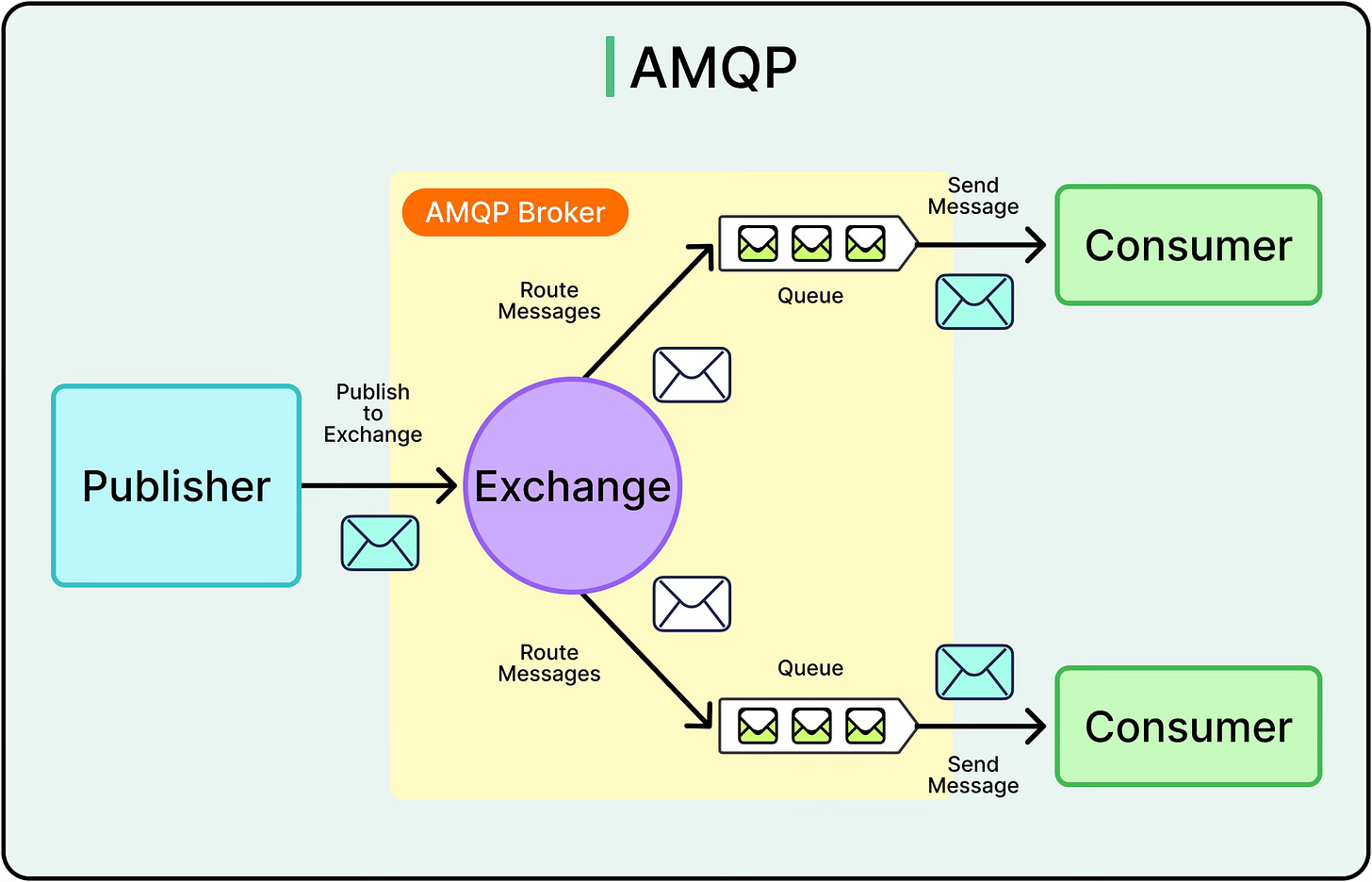

4 - AMQP

AMQP (Advanced Message Queuing Protocol) targets a different problem space: guaranteed message delivery, reliable queuing, and routing flexibility. It’s the backbone of systems that prioritize durability, decoupling, and recoverability.

See the diagram below:

RabbitMQ is the most common AMQP broker in production systems. It supports:

Persistent message queues

Publisher confirms and acknowledgments

Complex routing via exchanges (direct, topic, fanout)

Dead-letter queues for failed messages

AMQP shines in scenarios like:

Task queues where workers pull jobs asynchronously

Inter-service communication where one service triggers workflows in another

Systems that need message guarantees despite network failures or service crashes

Unlike HTTP, where failures are immediate and visible, AMQP introduces eventual delivery guarantees. Messages persist in queues until consumed or expired. This allows the sender and receiver to operate at different speeds, or even while offline.

However, this flexibility comes with complexity:

Retry logic, ordering guarantees, and duplicate suppression must be carefully managed

Monitoring and dead-letter handling require operational maturity

Message flow is harder to trace end-to-end

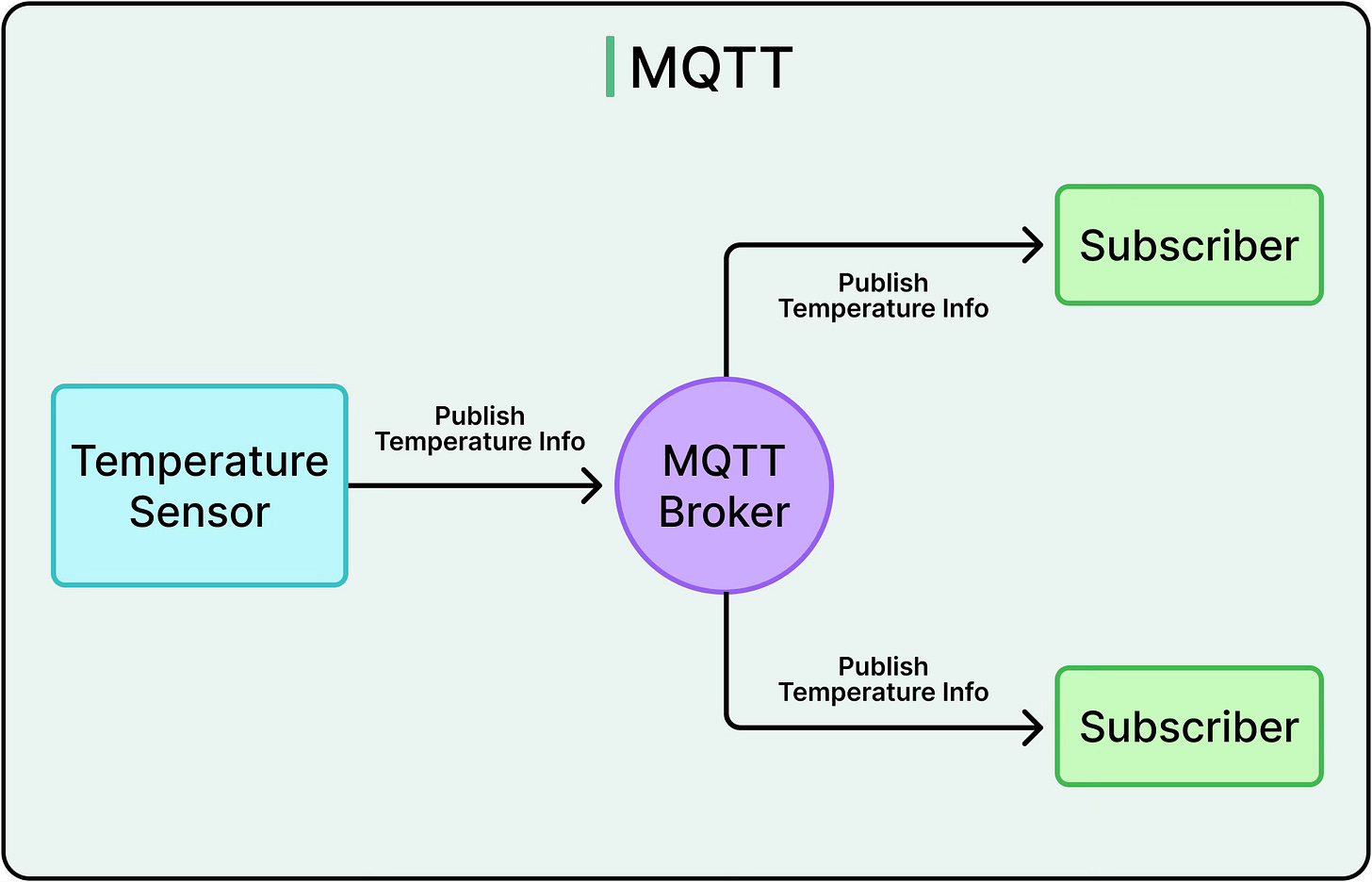

5 - MQTT

MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) is built for minimal overhead and unreliable networks. It’s a lightweight, asynchronous protocol widely used in IoT, mobile, and telemetry-heavy systems.

The MQTT model is publish-subscribe:

Clients connect to a broker and publish messages to topics

Other clients subscribe to those topics and receive updates

Brokers handle routing, connection management, and (optionally) message persistence

MQTT keeps the wire format tiny and supports:

QoS levels to define delivery guarantees (at most once, at least once, exactly once)

Persistent sessions, allowing clients to reconnect and resume

Retained messages, so late subscribers get the last known value

Ideal use cases for MQTT include:

Smart homes (thermostats, lights, locks)

Industrial monitoring and control

Mobile apps that need to operate under poor connectivity

MQTT favors battery efficiency, low bandwidth, and minimal processing. But it lacks the delivery guarantees and routing flexibility of AMQP.

Real-World Use Cases

Communication models don’t exist in isolation.

The choice between synchronous and asynchronous communication patterns shows up in the daily decisions developers make while building APIs, designing workflows, and scaling systems.

When to Use Synchronous Communication

Some interactions demand immediacy. In these cases, synchronous communication remains the default choice because the system depends on direct feedback.

Typical scenarios include:

User authentication: A login request needs an immediate “yes” or “no.” Waiting for an eventual response isn’t an option when gating access to protected resources.

UI interactions: When a user clicks “Place Order” or “Submit Form,” they expect a result within seconds, no matter the processing that happens in the background. The feedback loop must be tight for the users.

Database reads and immediate writes: Fetching the latest balance, verifying availability before booking, or saving a form directly to a record store are classic synchronous cases.

These use cases optimize for:

Strong consistency

Deterministic outcomes

Fast, user-facing feedback

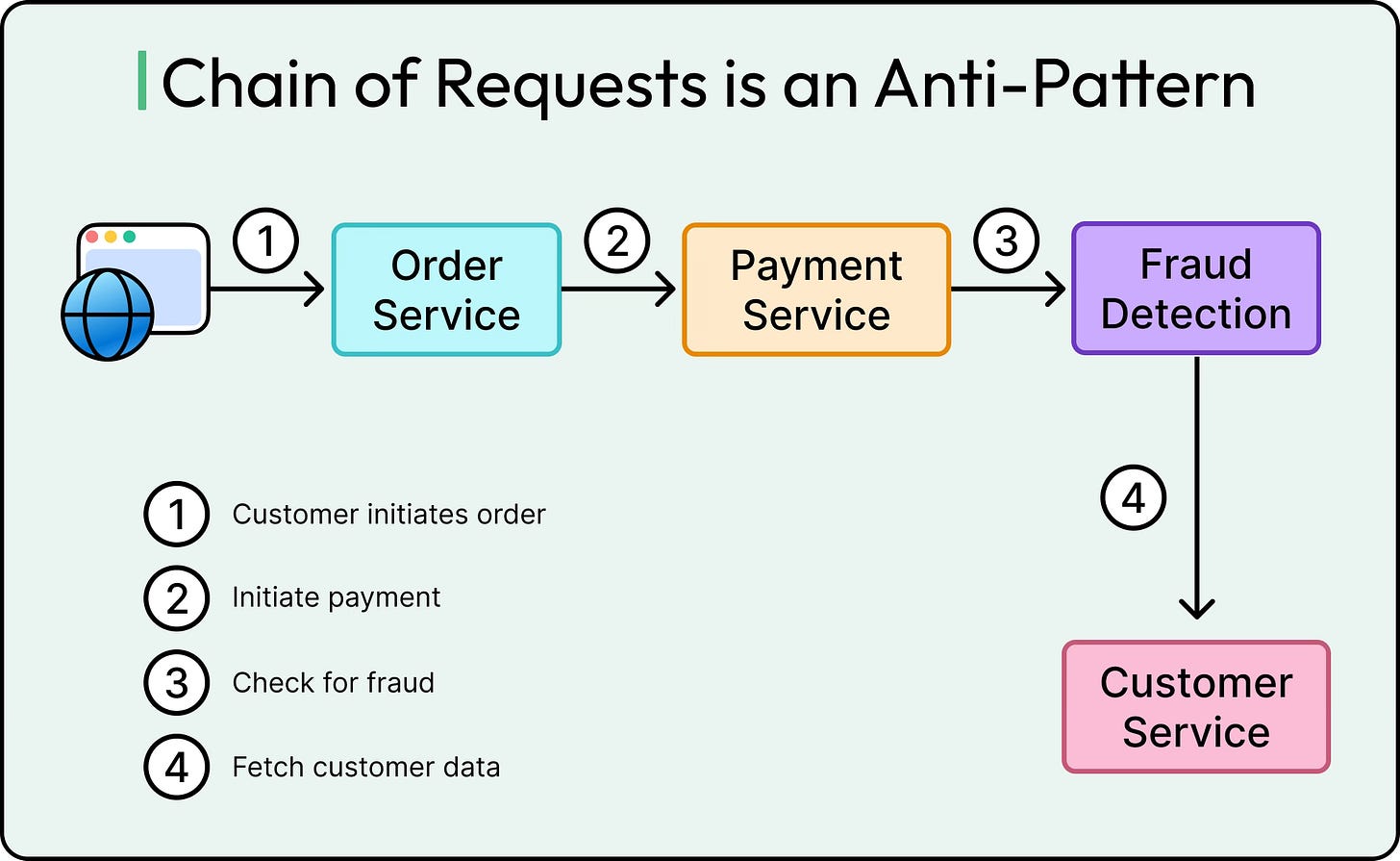

However, synchronous communication works best only when both parties are healthy and latency is low. Once the chain involves multiple hops, remote dependencies, or unreliable services, the risk of cascading delays grows.

When to Use Asynchronous Communication

In contrast, asynchronous communication fits when the work doesn’t need to block the user or the originating service.

If the outcome can arrive later, or if the work itself is too heavy to handle in-line, it makes sense to defer it through a queue, broker, or event bus.

Common examples include:

Order fulfillment: After a user places an order, confirming it synchronously is fine. But picking, packing, and shipping don’t need to happen in real time. Offloading those tasks to a background workflow improves throughput and resilience.

Email and notification systems: Few users care whether a confirmation email is sent in 50ms or 5 seconds. Decoupling notification delivery via a message queue avoids blocking critical user flows.

Image or video processing: Uploading a media file doesn’t mean a system must finish resizing or transcoding it before responding. Async pipelines allow processing to scale independently of user interactions.

Inventory synchronization: Backend systems syncing stock levels across warehouses or vendors can run on eventual consistency. Precision isn’t immediate; correctness over time matters more.

Asynchronous communication excels when:

Throughput matters more than latency

Tasks are long-running or resource-intensive

Systems need to continue operating under partial failure

Retry logic and durability are essential

The trade-off is visibility and control. Async systems require more infrastructure pieces and dead-letter handling, along with good monitoring capabilities.

Hybrid Use Case

In most modern architectures, neither model wins outright. Systems mix synchronous and asynchronous patterns to optimize for different phases of a workflow. The frontend might need immediate responses, while the backend quietly delegates heavy lifting to asynchronous pipelines.

Consider an e-commerce checkout:

The user submits an order and gets a success message from a synchronous API.

The system then publishes an event to trigger inventory checks, fraud detection, and invoice generation asynchronously.

These hybrid patterns show up often in:

API-first frontends calling a service that queues jobs for backend processing

Request-acknowledge-confirm flows, where the initial request is synchronous, but the result comes later through polling or a webhook

Fan-out systems, where one synchronous trigger initiates multiple asynchronous consumers downstream

Blending sync and async models requires discipline:

Clearly define boundaries between immediate and deferred steps

Use correlation IDs to track workflows end-to-end

Build monitoring that captures both fast failures and slow drifts

The sweet spot lies in balancing responsiveness with robustness. Synchronous interactions keep the system usable. Asynchronous workflows keep it scalable. The best systems know where to place the boundaries.

Trade-Offs

Communication models aren’t interchangeable. Each one carries implications for system behavior under load, in failure, and during evolution. A design that performs well in testing can break down in production if the trade-offs aren’t well understood.

Performance and Latency

Synchronous calls are direct, but they often become chokepoints under pressure. Every synchronous request ties up system resources while waiting. If the downstream service slows down or hits saturation, the latency ripples backward. At scale, this creates head-of-line blocking and queue buildup, not just in the service itself, but across the entire call chain.

Asynchronous systems handle this differently. By introducing queues or event buffers, they absorb traffic spikes and prevent upstream components from getting stuck. Tasks can pile up without immediately affecting the caller. This improves throughput, especially for background workloads or deferred execution.

However, that throughput comes at the cost of latency in completion. A message may sit in a queue for seconds or minutes, and consumers may process unevenly. Systems that need fast end-to-end response, like fraud detection or search autocomplete, can’t always afford that delay.

There’s also operational overhead:

Message serialization (for example, JSON, Protobuf) adds CPU cost.

Delivery guarantees (for example, "at least once") introduce retries, duplication, and deduplication logic.

Reliability and Fault Tolerance

Synchronous systems often fail fast. When a downstream dependency crashes, timeouts and errors bubble up instantly. That makes failures easy to detect, but also means that one broken service can bring down others. A missed timeout setting or a retry storm can turn a minor glitch into a cascading outage.

Asynchronous communication introduces insulation. If Service A sends a message to a queue, it doesn’t matter whether Service B is online right now. As long as the broker is durable, the message will sit there until B is ready. This decoupling improves availability and fault tolerance, especially across services owned by different teams or deployed in different regions.

But it comes with responsibilities:

Dead-letter queues must handle poison messages that fail repeatedly.

Retries must avoid flooding consumers or causing duplicate side effects.

Idempotency is essential, especially for financial transactions or state mutations.

In general, asynchronous systems survive failure better, but they need more operational safety nets. Without those, failure can go unnoticed.

Complexity and Observability

Simplicity favors synchronous design. The flow is linear: request in, response out. Logs tell a coherent story. Stack traces show what went wrong. Metrics like response time and error rate are easy to capture and reason about.

Asynchronous systems, by contrast, fracture visibility. Understanding why something failed or even whether it did requires end-to-end tracing, correlation IDs, structured logs, and sometimes, guesswork.

Key tooling requirements include:

Distributed tracing systems (for example, OpenTelemetry, Zipkin, Jaeger)

Structured log aggregation

Retry/backoff policy monitoring

Alerting on lag, failure, or undelivered messages

Developer Experience

Most developers learn synchronous communication first. REST and HTTP are easy to experiment with, debug, and reason about. Curl, Postman, browser DevTools—they’re everywhere. Modern web frameworks (Spring Boot, Express.js, Django, .NET Core) make building REST APIs nearly frictionless.

Async messaging, by contrast, requires deeper infrastructure understanding. Running a broker like RabbitMQ isn’t trivial. Developers must think in terms of producers, consumers, brokers, topics, and offsets.

Some platforms help bridge the gap:

Spring Cloud Stream (Java) abstracts broker details

NestJS (Node.js) supports event-driven architecture patterns

Azure Functions or AWS Lambda offer event-based execution models

Protocol Suitability

Each protocol comes with its assumptions, tooling expectations, and operational costs. The right fit depends on factors like latency tolerance, message durability, device constraints, and interaction patterns.

Here are a few heuristics that can help:

Use HTTP/REST when clarity, simplicity, and immediate responses matter. It’s the go-to choice for APIs that need predictable, request-response behavior. Most frontend-to-backend interactions fall in this category. The broad tooling ecosystem, human-readable payloads, and stateless nature make it easy to test, debug, and evolve. REST works well for internal microservices too, as long as performance and strict availability aren’t major constraints.

Use WebSocket when real-time, two-way updates are essential. WebSocket fits scenarios where both the client and server need to push data to each other continuously, without constantly opening new connections.

Use gRPC when performance, contract-first design, and inter-service efficiency are priorities. gRPC is particularly suited to backend-to-backend communication in microservice-heavy architectures.

Use AMQP when delivery guarantees, message routing, and decoupled workflows are critical. In systems where reliability is more important than immediacy, such as order fulfillment, email delivery, billing, or background job processing, AMQP provides a rich set of features around acknowledgments, retries, and flexible routing.

Use MQTT when dealing with IoT devices, unreliable networks, or bandwidth-constrained environments. Its publish-subscribe model and lightweight wire protocol make it ideal for scenarios like smart home devices, industrial sensors, or mobile applications that need to maintain persistent connections with minimal overhead.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at synchronous and asynchronous communication in detail, along with protocols and real-world use cases.

Let’s summarize the key learning points in brief:

Synchronous communication involves a request-response model where both parties must be online and responsive at the same time. It is straightforward to reason about, but fragile under latency or failure.

Asynchronous communication decouples the sender and receiver in time, allowing systems to absorb spikes in traffic and tolerate partial failure. It increases resilience and throughput but adds complexity in monitoring and error handling.

HTTP/REST is the default protocol for synchronous communication due to its simplicity, ecosystem support, and stateless design. It’s ideal for CRUD APIs, frontend-backend interactions, and short-lived service calls.

WebSocket maintains long-lived, bidirectional connections and is suited for real-time applications like chat, live dashboards, or collaborative editing. It offers a more interactive experience but requires explicit connection management.

gRPC enables high-performance communication between services using strongly typed contracts and efficient binary serialization. It supports both synchronous and streaming models and is ideal for service meshes and internal APIs.

AMQP is a protocol built for reliability, message routing, and guaranteed delivery. It powers background job systems, decoupled workflows, and enterprise-grade message queues through tools like RabbitMQ.

MQTT is designed for resource-constrained devices and flaky networks. Its lightweight publish/subscribe model and persistent connections make it a natural fit for IoT, telemetry, and mobile use cases.

Synchronous communication is best used when real-time feedback or strong consistency is required, like payments, logins, or UI actions.

Asynchronous communication works well when tasks can be deferred or completed independently, like order processing, media uploads, or sending notifications.

Hybrid models are common in production systems. For example, a synchronous API call may trigger an asynchronous workflow in the background to offload heavy processing.

Synchronous systems are easier to trace and debug, but can become bottlenecks under high load or failure. Asynchronous systems scale better but demand stronger observability and operational safeguards.

Choosing a protocol should depend on use case constraints such as latency tolerance, message durability, client capabilities, and system coupling, not just developer familiarity or tooling preference.