Imagine a ride-sharing app that shows a driver’s location with a few seconds of delay. Now, imagine if the entire app refused to show anything until every backend service agreed on the perfect current location. No movement, no updates, just a spinning wheel.

That’s what would happen if strong consistency were always preferred in a distributed system.

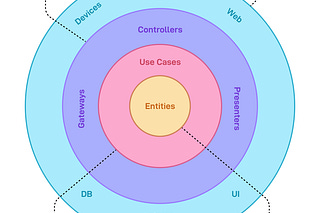

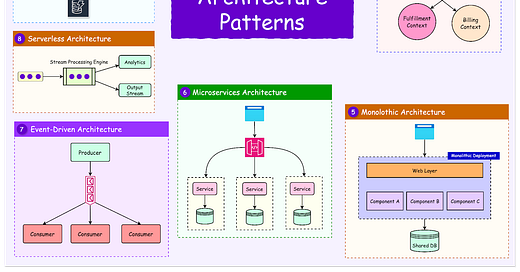

Modern applications (social feeds, marketplaces, logistics platforms) don’t run on a single database or monolithic backend anymore. They run on event-driven, distributed systems. Services publish and react to events. Data flows asynchronously, and components update independently. This decoupling unlocks flexibility, scalability, and resilience. However, it also means consistency is no longer immediate or guaranteed.

This is where eventual consistency becomes important.

Some examples are as follows:

A payment system might mark a transaction as pending until multiple downstream services confirm it.

A feed service might render posts while a background job deduplicates or reorders them later.

A warehouse system might temporarily oversell a product, then issue a correction as inventory updates sync across regions.

These aren’t bugs but trade-offs.

Eventual consistency lets each component do its job independently, then reconcile later. It prioritizes availability and responsiveness over immediate agreement.

This article explores what it means to build with eventual consistency in an event-driven world. It breaks down how to deal with out-of-order events and how to design systems that can handle delays.

What is Eventual Consistency?

Picture a group of friends agreeing on where to meet for dinner over text. One friend suggests a coffee shop, another proposes a restaurant, and a third doesn’t see the messages until later. For a few minutes, everyone believes something different. But given enough time, messages get delivered, responses come in, and the group eventually aligns on a single place. The confusion doesn’t last forever. It just takes a few exchanges to settle.

That’s eventual consistency in a nutshell.

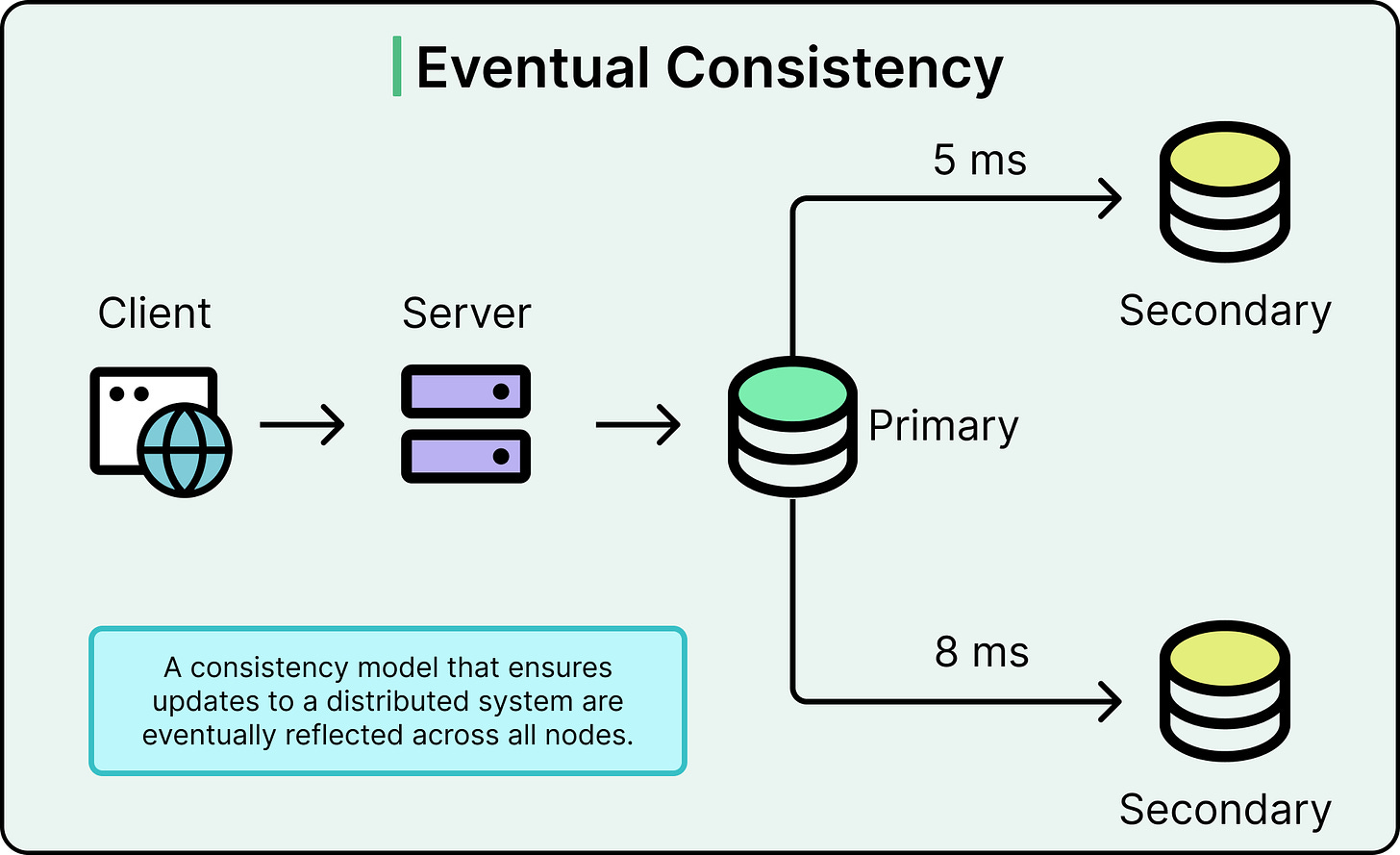

In distributed systems, eventual consistency means that different parts of the system (databases, caches, services) may hold different views of the data at any given moment. But if no new updates happen, the system guarantees that all parts will eventually converge to the same final state.

Systems built around eventual consistency do not enforce strict ordering or synchronized updates across nodes. Instead, they tolerate short-term divergence. For example:

A product inventory might show "in stock" on one server and "out of stock" on another for a few seconds.

A notification service might send an alert slightly before the related database record fully updates.

As updates propagate asynchronously, the differences resolve. Eventually, every healthy part of the system will reflect the same truth. The key concept to understand here is the window of inconsistency. During this window:

Reads might return stale or partial data.

Different services might act on slightly different versions of the data..

Clients might observe anomalies like "missing" or "outdated" information.

Understanding this window matters because it shapes how systems behave under real conditions. The wider the window, the greater the chance users will notice inconsistencies. Systems can shrink the window by tuning replication speeds, retry strategies, and consistency protocols, but shrinking it to zero demands strong consistency, and with it, a steep trade-off in availability and latency.

A few important truths about eventual consistency:

It is not eventual correctness. Systems still need robust conflict resolution and reconciliation logic to ensure the final state makes sense.

It does not guarantee order. Events may arrive in different orders at different nodes.

It is not laziness. Choosing eventual consistency is an engineering decision based on speed, availability, and resilience trade-offs.

In practice, almost every large-scale, high-availability system leans into eventual consistency somewhere. Shopping carts, messaging apps, and document collaboration tools each allow short-lived inconsistencies because waiting for perfection would destroy usability.

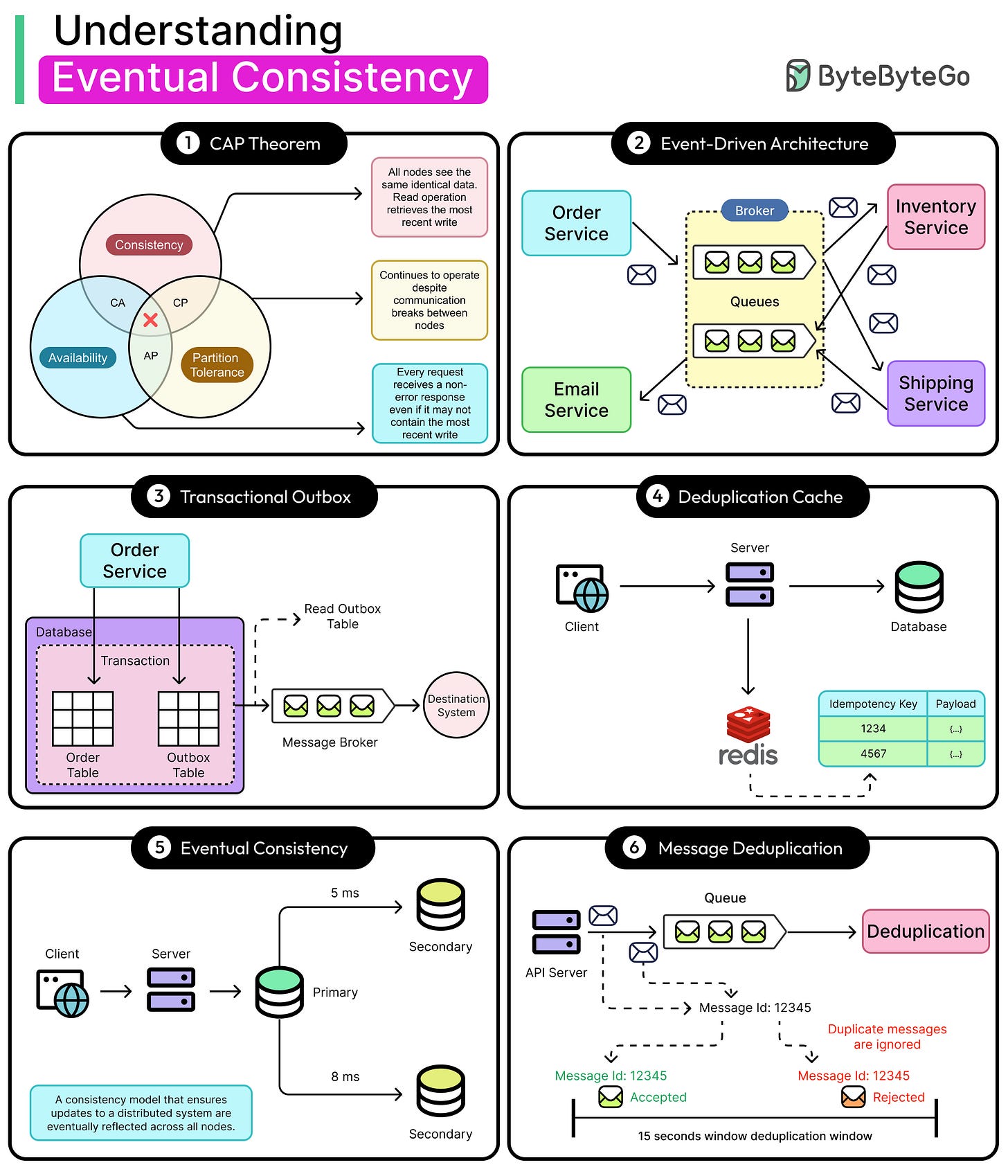

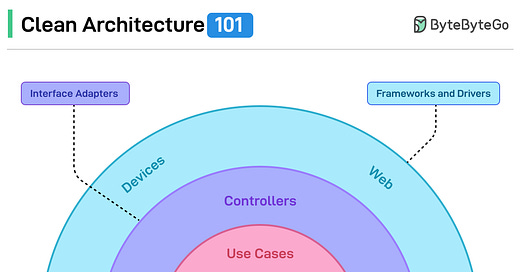

Event-Driven Architecture and the Role of Events

Every time a user taps a button, places an order, or uploads a photo, something changes inside a system. In traditional designs, the system often tries to immediately update all necessary records, locking resources and coordinating across services in real-time.

Event-Driven Architecture (EDA) takes a different approach. It treats every meaningful change as an event: a standalone, immutable fact about something that happened.

Instead of tightly wiring actions together, services publish and react to events asynchronously.

An event is simply a record: "User A placed Order 123", "Driver B started Trip 456," "Photo X was uploaded by User Y." It captures what happened, not what to do next. This subtle difference changes everything. In an event-driven system:

One service produces an event when its local state changes.

Other services consume that event to trigger their updates or workflows.

Services communicate by sharing facts, not by commanding each other directly.

This decoupling brings enormous benefits in the following cases:

Scalability: Producers and consumers scale independently.

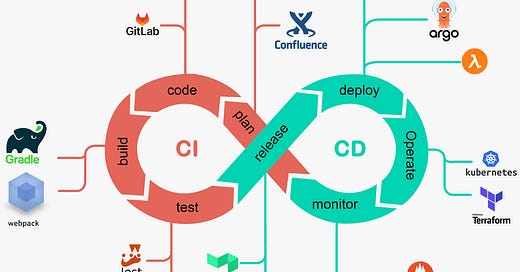

Resilience: Failures are contained. If a consumer goes down, it can catch up later.

Flexibility: New consumers can subscribe to old events without needing the producer to change.

A social media platform provides a familiar example. When a user posts a photo:

The upload service emits a "Photo Uploaded" event.

The newsfeed service consumes it to insert the post into followers’ timelines.

The analytics service tracks the event to update engagement metrics.

The notification service alerts friends.

These services don’t call each other directly. They react to a shared event asynchronously, each on its own timeline.

This loose coupling, however, introduces new challenges. Events can:

Arrive out of order if network delays or retries shuffle delivery.

Arrive late if a downstream service processes a backlog.

It will be duplicated if a producer retries after a timeout.

Disappear if the infrastructure fails without strong guarantees.

Systems built on EDA must plan for these realities.

Consuming an event is not the same as executing a synchronous API call. Services must account for partial information, deal with inconsistencies, and design for resilience. Since each consumer interprets events independently, coordination across services becomes probabilistic, not absolute. This is where eventual consistency becomes essential. When updates flow through events, temporary inconsistency is inevitable.

A good event-driven design treats events as the ultimate source of truth: immutable, timestamped, and reliable enough to rebuild state if needed. They also treat event flow as a first-class concern, with storage, monitoring, and failure recovery built in.

Why Strong Consistency is Hard in Event-Driven Systems?

Strong consistency, where every read sees the latest write, sounds like a good goal for a system. In a perfect world, systems would behave like tightly managed filing cabinets: open the drawer, and the latest document is always neatly updated.

Distributed systems don’t live in that world. They live in the real one, full of network delays, service crashes, retries, partitions, and unpredictable failures. Trying to enforce strong consistency in an event-driven architecture means fighting against the nature of distributed computing itself.

Consider a simple case: a user submits a review for a product. The review service emits an event: "Review Created." Downstream, the analytics service updates average ratings, and the user profile service logs the user’s contribution count. If one service updates immediately and another lags (or worse, processes events out of order), the system briefly reflects different realities.

Strong consistency would demand that either all services complete successfully, or none do. In an asynchronous, event-driven world, that’s a tall order. The problem starts with the fallacies of distributed computing:

The network is reliable.

Latency is zero.

Bandwidth is infinite.

The topology doesn't change.

Each of these assumptions falls apart in practice. Networks lose packets, and services go down. Messages queue up unpredictably. An event that seems “sent” from one service can silently fail to reach another. When systems rely on asynchronous messaging, these uncertainties multiply.

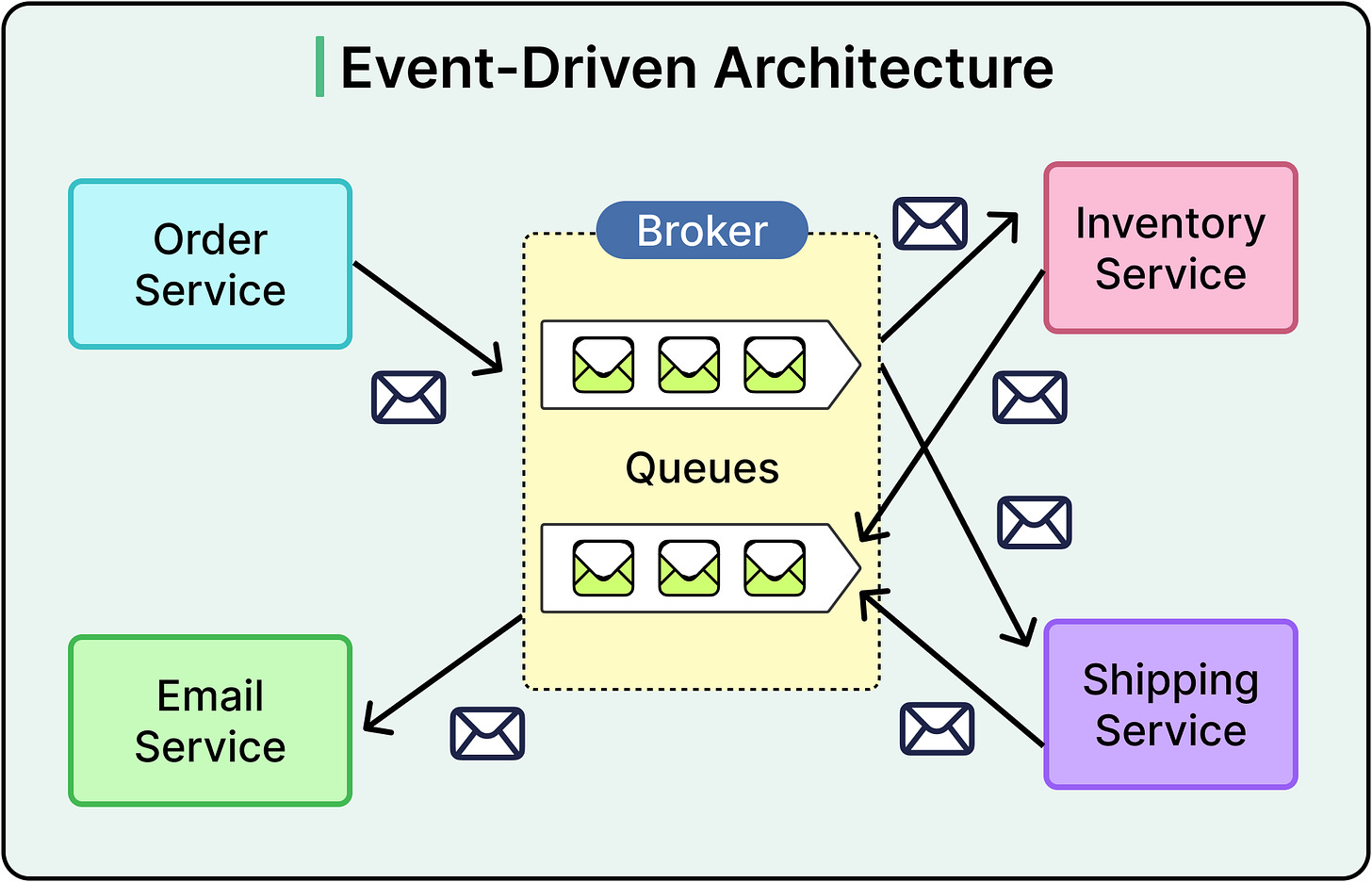

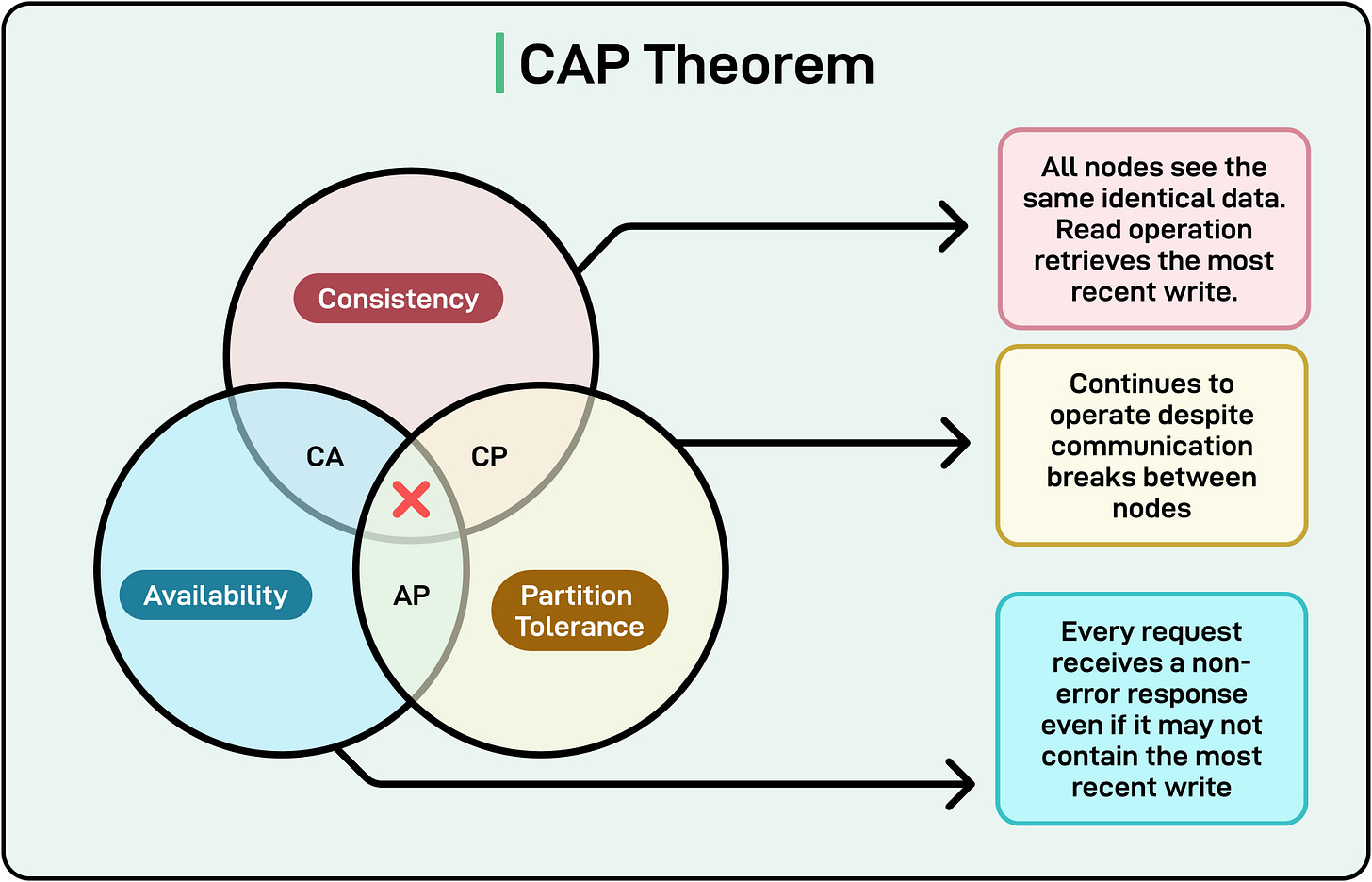

The CAP theorem formalizes this reality. It states that in any distributed system, it’s impossible to guarantee the following three properties at the same time:

Consistency (every read sees the latest write)

Availability (every request receives a response, even if not the latest)

Partition Tolerance (the system continues despite network failures)

When partitions happen, systems must choose between consistency and availability.

In event-driven architectures, availability almost always wins. Users expect systems to stay responsive even during network hiccups. Waiting for every service to agree before showing any result would stall the system. Instead, systems opt to be available but temporarily inconsistent, trusting that eventual consistency will clean things up later.

This isn’t to say strong consistency is useless. Some domains (financial transactions, critical state transitions) genuinely require it. But applying it everywhere, especially across loosely coupled, asynchronous services, leads to fragility rather than strength.

Handling Out-of-Order Events

In distributed systems, out-of-order events are not a rare glitch but an everyday fact.

Therefore, systems must be designed for messier realities. Left unchecked, out-of-order events can create subtle bugs: updates overwriting each other incorrectly, stale views appearing to users, or invalid state transitions slipping through.

Some strategies to handle out-of-order events are as follows:

Event Versioning

Each event should carry a version or sequence number representing the state it describes.

When a service processes an event, it compares the incoming version to the current version it holds:

If newer, apply the event.

If older, discard or ignore it.

If duplicate, treat idempotently.

Without versioning, a late-arriving event could overwrite a later event, undoing progress.

Systems like DynamoDB and Couchbase often rely on internal versioning (using vector clocks or document revisions) to resolve update conflicts safely.

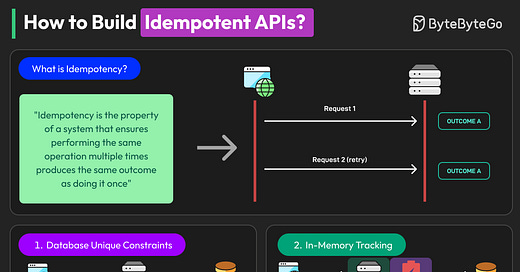

Idempotent Event Handlers

Idempotency guarantees that processing the same event multiple times produces the same result.

This principle protects systems when events retry, duplicate, or reorder. Techniques for achieving idempotency include:

Recording processed event IDs to skip duplicates.

Structuring updates to be overwrite-safe, not additive (for example, "set order status to SHIPPED" instead of "increment shipment counter").

Using conditional writes or compare-and-swap operations at the storage layer.

Reordering Buffers

When events arrive slightly out of order but with predictable patterns (such as sequential numbering), services can use reordering buffers:

Hold a small window of recent events.

Reorder them based on version or timestamp.

Process them once the sequence stabilizes.

For example, a messaging app might buffer incoming chat messages for a few seconds before rendering, ensuring that "Hello" appears before "How are you?" even if the packets crossed paths en route.

The trick is tuning the buffer size and timeout carefully. Too small, and out-of-order events slip through. Too large, and latency balloons unnecessarily.

State Reconciliation: Fixing Inconsistencies Later

Sometimes, no buffering or reordering strategy can guarantee a clean state at ingestion time. In these cases, systems build reconciliation jobs that periodically scan, compare, and fix inconsistencies:

Missing shipment updates? Re-sync from event logs.

Out-of-sync inventory counts? Recompute aggregates from ground-truth records.

Event sourcing systems like those built on Kafka or EventStore often rely on replayable logs to rebuild the correct state from a messy sequence of events.

Reconciliation shifts the mindset from "prevent all mistakes" to "detect and fix mistakes quickly."

Idempotency and Duplicate Event Handling

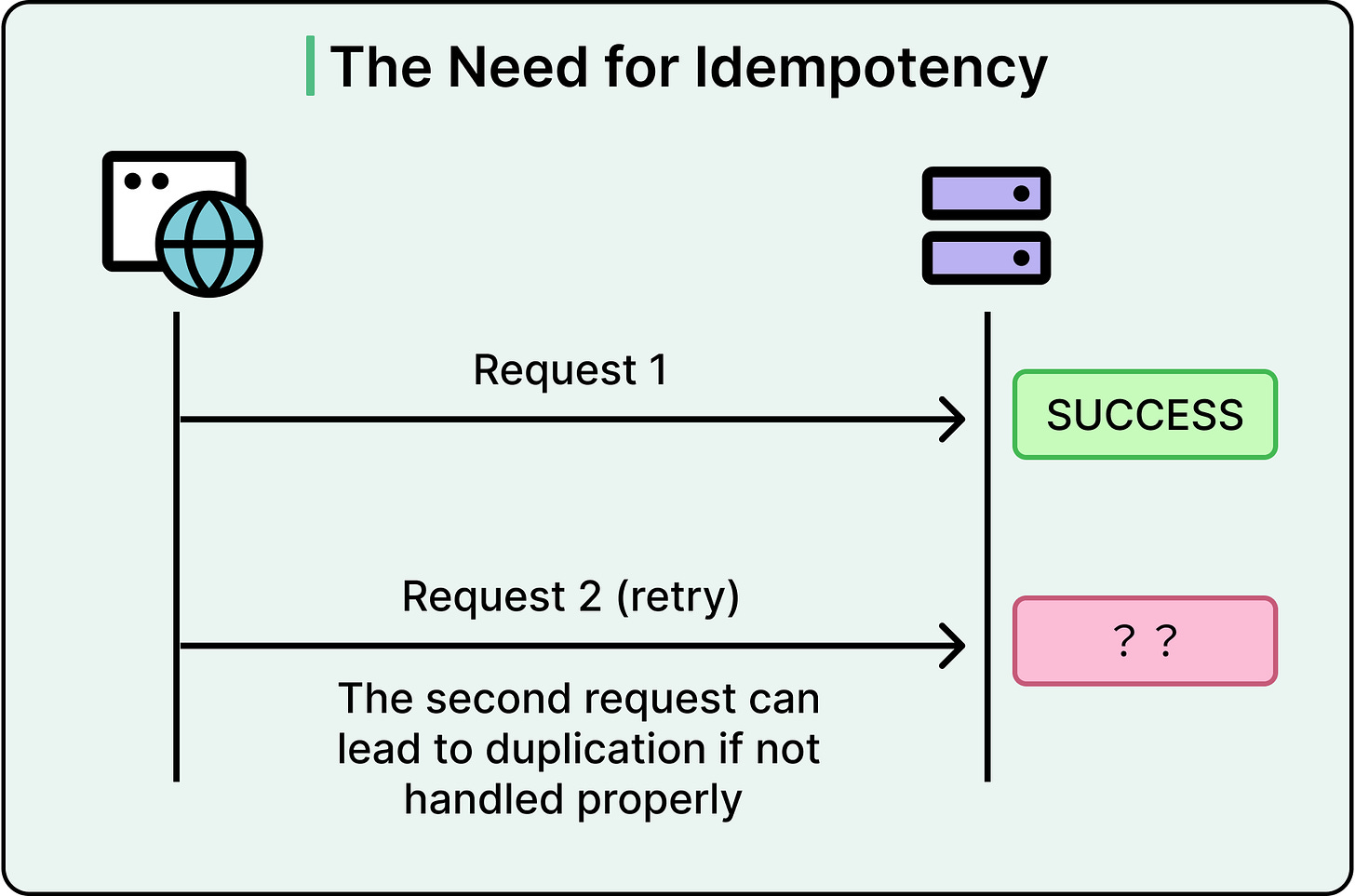

In a perfect world, each event would deliver exactly once, arrive on time, and trigger exactly one reaction.

However, in real systems, retries happen. Messages are duplicated, and services crash mid-process. Handling duplicates is not an edge case.

This is where idempotency steps in.

Idempotency means that processing the same event multiple times produces the same result as processing it once. No side effects multiply, no records corrupt, no counters inflate.

Why Duplicates Happen Even in "Reliable" Systems?

No messaging system fully guarantees perfect, exactly-once delivery in all conditions. Common patterns where duplicates sneak in are as follows:

A producer sends an event, but the network acknowledgment fails. It retries, unaware that the original succeeded.

A consumer processes an event, but crashes before acknowledging completion. The system re-delivers.

A broker like Kafka retries dispatch during leader election or client failover.

Protocols like at-least-once delivery prioritize availability: it’s better to risk duplicates than lose events entirely. The burden shifts to application logic to handle duplicates appropriately.

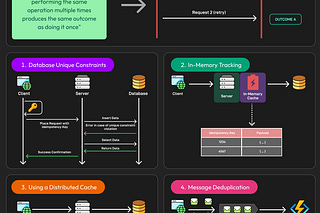

Core Strategies for Achieving Idempotency

Some key strategies can be used to achieve idempotency:

1 - Event IDs

Each event should carry a globally unique event ID:

Before processing, a consumer checks whether the event ID has been seen.

If yes, it discards or safely no-ops.

If no, it processes and records the ID as handled.

This approach forms the backbone of idempotent processing in systems like payment platforms, where recharging a user twice would be catastrophic.

Key considerations are as follows:

The event ID must be truly unique across retries and failures.

The lookup store for processed IDs must be consistent and performant, or risk becoming a bottleneck.

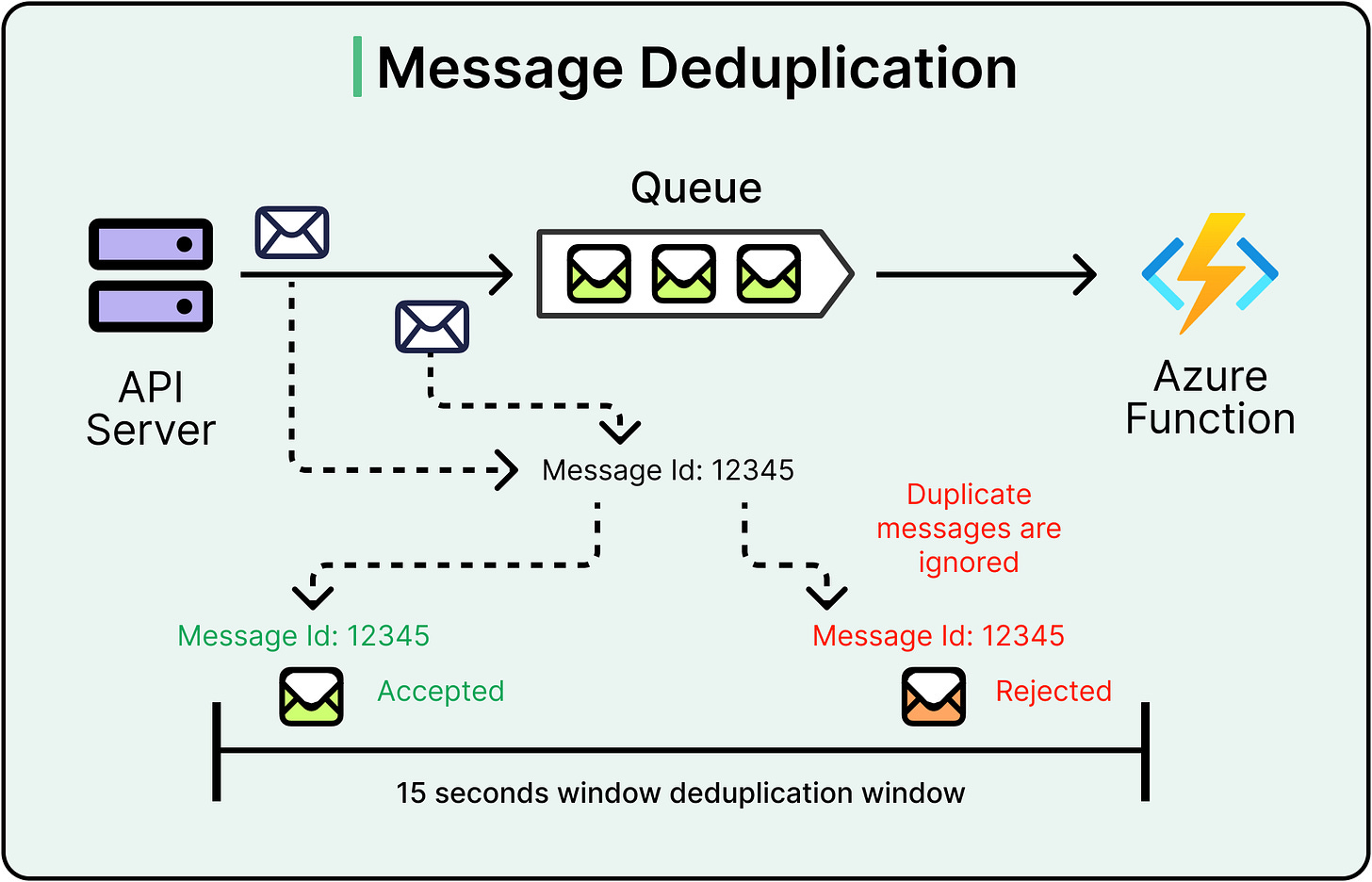

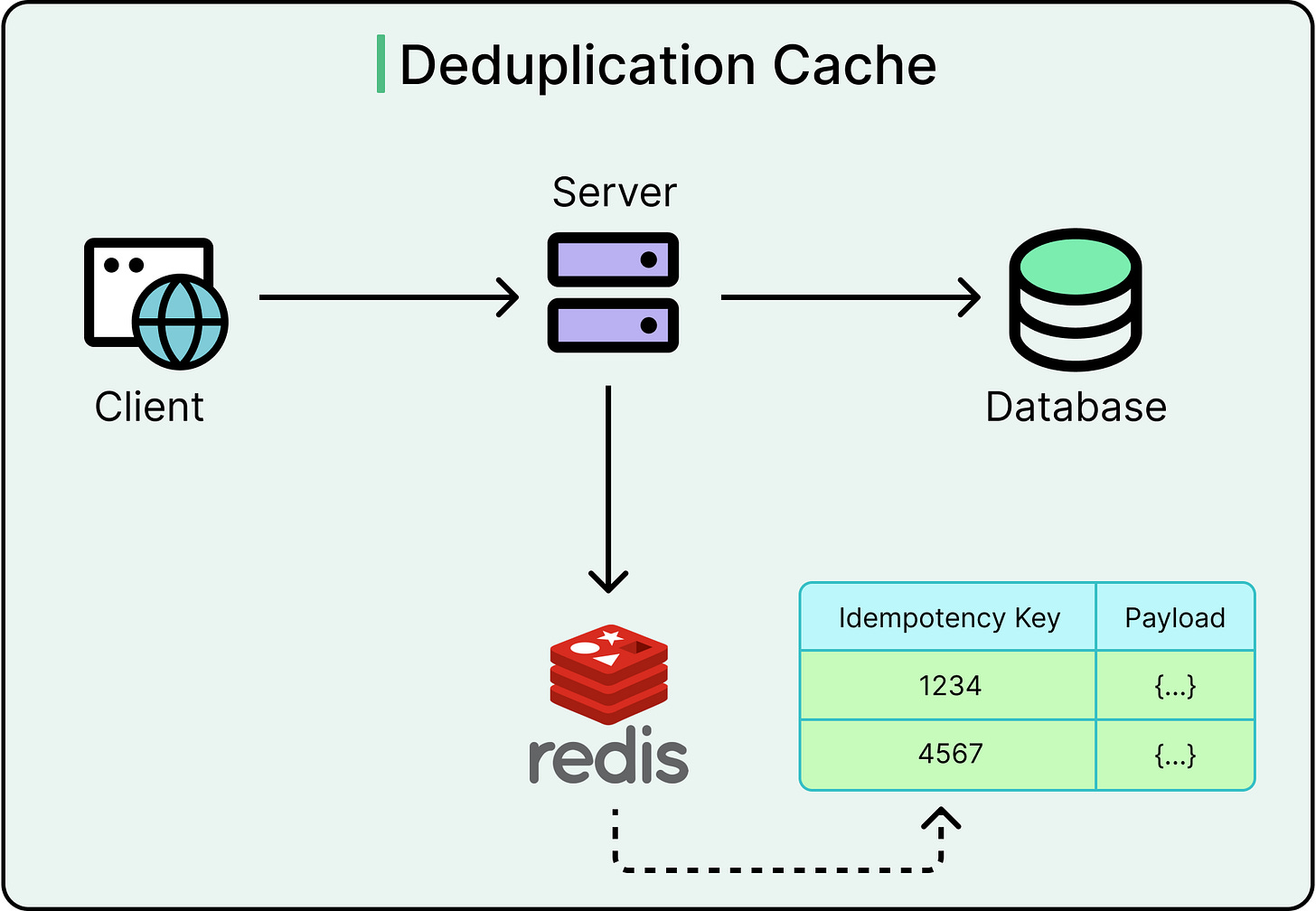

2 - Deduplication Caches

Not every system can afford to track every event ID forever. Deduplication caches offer a middle ground:

Keep recent event IDs in an in-memory store (like Redis) with a time-to-live (TTL).

Assume that true duplicates will show up within a reasonable retry window.

This balances correctness against resource cost. Missed rare duplicates outside the cache window are a risk, but an acceptable one for many non-critical systems (for example, analytics pipelines and feed generators).

3 - Natural Idempotency

Sometimes systems can achieve idempotency by design, without tracking event IDs:

Set order status to "SHIPPED" instead of incrementing a shipment counter.

Save user profile updates as overwrites rather than applying deltas.

Replace entire shopping cart contents, not just append to them.

When actions naturally overwrite state rather than mutating it incrementally, retries have no lasting negative effects.

This approach shines in document-based stores like DynamoDB, Couchbase, or even S3 object storage.

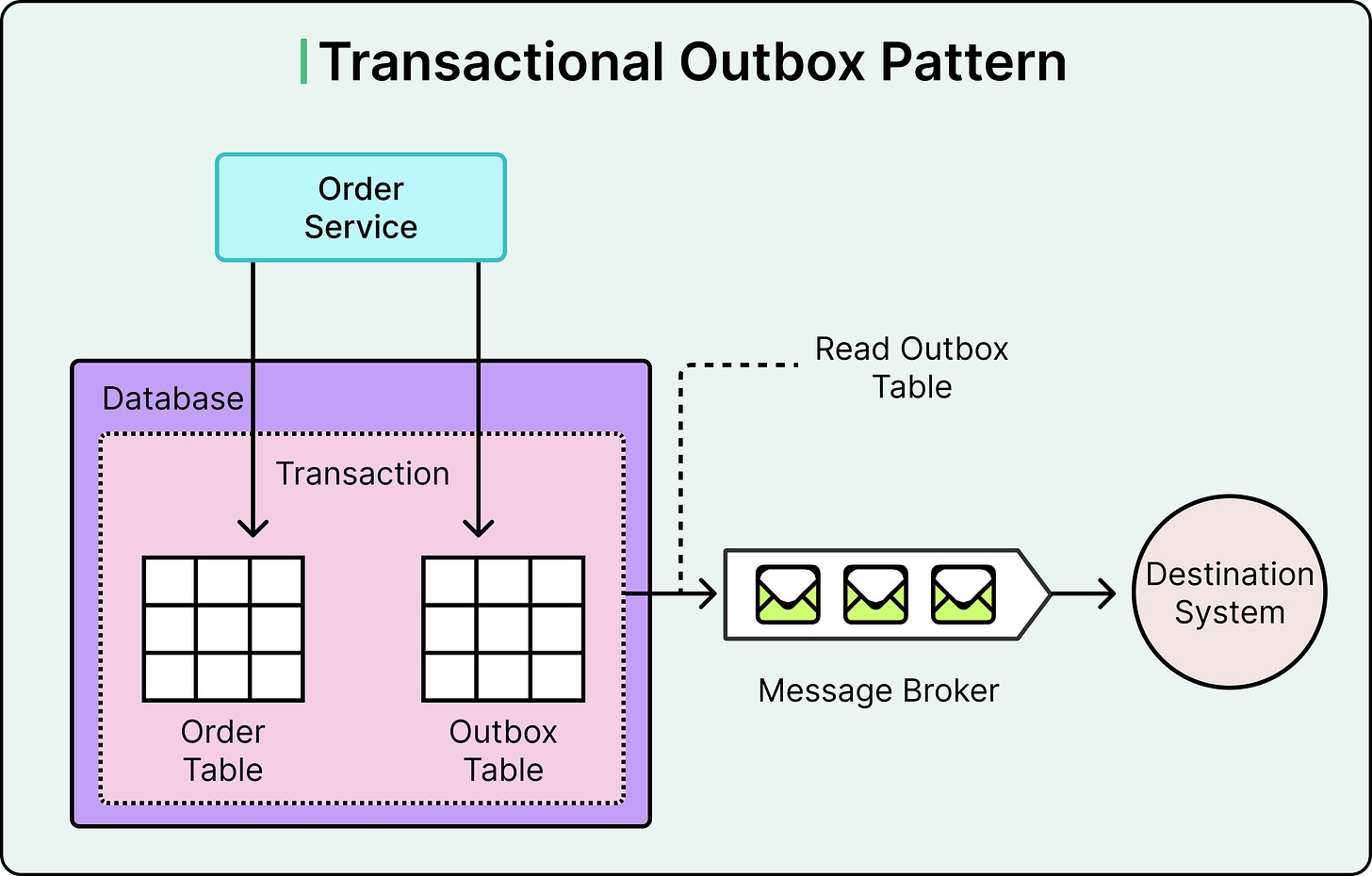

4 - Transactional Writes

Databases that support atomic operations can combine "check if event ID exists" and "apply changes" into a single transactional write:

Insert event ID and update state atomically.

If the ID already exists, the insert fails, and the state remains unchanged.

This eliminates race conditions and ensures exactly-once behavior inside the database boundary, even if the messaging layer outside remains messy

Dead Letter Queues (DLQs)

Every event-driven system eventually runs into a message it cannot process. Some common causes could be:

Malformed payload

A dependent service is down.

The business logic changes, and older events no longer fit.

When this happens, systems have a choice: either keep retrying forever, risking resource exhaustion and backlog, or isolate the problematic event and move forward. This is the role of a Dead Letter Queue (DLQ).

A Dead Letter Queue is a secondary queue used to hold events that a system has repeatedly failed to process. It acts as a safety valve, separating poison events from healthy ones to preserve overall system flow.

Without DLQs, a single bad event can stall entire processing pipelines by retrying endlessly, burning CPU, piling up latencies, and masking real throughput.

How DLQs Work

Here’s a step-by-step process:

An event enters a consumer or processor.

Processing fails due to invalid data, missing dependencies, or internal errors.

The system retries processing, either immediately or after a delay.

After a configurable number of retries (or elapsed time), the system gives up.

Instead of discarding the event silently, it is moved to the Dead Letter Queue for further inspection.

DLQs preserve valuable information about failed events, such as the payload that caused the failure, the error thrown, and the responsible system.

Common Mistakes and Anti-Patterns in Eventual Consistency

Here are some of the most common traps, and how better designs sidestep them.

1 - Over-Retrying Without Dead-Lettering

One common mistake in event-driven systems is blindly retrying failed events indefinitely without isolating the ones that will never succeed, often called "poison messages."

This approach clogs processing queues, blocks healthy events from progressing, and causes latency to spike as the system repeatedly burns resources on the same failures. Over time, these retries flood processing threads, starve legitimate workloads, and degrade overall throughput.

A better approach is to implement bounded retries with exponential backoff, and redirect persistently failing events into a dead-letter queue (DLQ) after a configured threshold. The DLQ acts as a quarantine area for problematic events, allowing systems to move forward while giving operators the ability to inspect and resolve the underlying issue manually.

2 - Tight Coupling

Another common pitfall in event-driven architecture is designing services that cannot process events independently, relying instead on immediately invoking other services during event handling.

This pattern quietly reintroduces tight, synchronous coupling: the very thing event-driven systems are meant to avoid. When one service depends on a downstream call to proceed, the whole chain becomes fragile. A single slowdown or failure propagates upstream, turning isolated hiccups into cascading outages. In the process, the system loses most of the resilience and scalability that event-driven design promises.

The better alternative is to build services that consume events autonomously. Each service should be able to process an event, update its local state, and move forward without waiting on others. When coordination is truly necessary, use established patterns like the outbox pattern, sagas, or compensating transactions to manage cross-service workflows asynchronously.

These approaches preserve the independence of each component while still supporting distributed workflows.

3 - Assuming Events Always Arrive in Order

A frequent and subtle mistake in event-driven systems is building logic that assumes events will always arrive in the exact order they were produced.

This assumption rarely holds in real-world distributed environments.

Robust systems don’t rely on perfect order. Instead, they are designed to tolerate out-of-order events. This means using event versions or timestamps to determine whether a given update should be applied or safely discarded as stale. For cases where ordering matters (such as financial transactions or user state transitions), engineers can introduce reordering buffers or periodic reconciliation jobs to restore correct sequences.

4 - Ignoring Idempotency

A critical mistake in event-driven systems is writing event handlers that blindly mutate state, assuming each event will only ever arrive once.

In practice, duplicates are inevitable.

Messages get retried, consumers crash mid-processing, and brokers re-deliver during failover. Without safeguards, these retries can wreak havoc: double shipments, duplicate charges, inflated counters, and broken aggregates are all common symptoms of non-idempotent handling.

The solution is to design every handler to be idempotent from the start. This involves tracking event IDs to detect and skip duplicates, overwriting state instead of incrementing, and using conditional writes or transactions to enforce consistency under concurrent access.

In event-driven systems, idempotency is a baseline requirement for correctness and resilience in the face of real-world uncertainty.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at eventual consistency in event-driven architecture in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Eventual consistency is a deliberate design choice that enables distributed systems to remain available and resilient, even when components temporarily disagree.

In event-driven systems, eventual consistency means that all services will converge on the same state over time, even if they observe or process events at different moments.

Events capture changes in system state and enable loosely coupled services to react asynchronously, but this flexibility comes with the challenge of handling delays, duplicates, and disorder.

Strong consistency is difficult to enforce in distributed, asynchronous systems due to inherent network instability, coordination costs, and CAP theorem trade-offs; favoring availability and autonomy is often more practical.

Out-of-order events are common due to retries, network delays, and partitioned processing, so systems must use techniques like versioning, timestamps, idempotent handlers, and reordering buffers to maintain correctness.

Idempotency is essential in event handling to ensure that duplicate events do not cause side effects or state corruption, and must be baked into handler logic using event IDs, safe updates, and transactional guarantees.

Dead-letter queues protect pipelines by isolating unprocessable events after retries fail, allowing healthy traffic to continue and giving operators a window into systemic issues through inspection and alerting.

Many failures in event-driven consistency stem from design anti-patterns, such as uncontrolled retries, tight service coupling, assumptions about event order, non-idempotent handlers, and lack of durable storage, which undermine system robustness.