Modern software rarely lives on one machine anymore. Services run across clusters, web applications are dynamically rendered on the browser, and data resides on a mix of cloud platforms and in-house data centers.

In such a scenario, coordination becomes harder, latency becomes visible, and reliability is crucial. In this environment, messaging patterns become a key implementation detail.

When two services or applications need to talk, the simplest move is a direct API call. It’s easy, familiar, and synchronous: one service waits for the other to respond. But that wait is exactly where things break.

What happens when the downstream service is overloaded? Or slow? Or down entirely? Suddenly, the system starts to stall: call chains pile up, retries back up, and failures increase drastically.

That’s where asynchronous communication changes the game.

Messaging decouples the sender from the receiver. A service doesn’t wait for another to complete work. It hands off a message and moves on. The message is safely stored in a broker, and the recipient can process it whenever it's ready. If the recipient fails, the message waits. If it’s slow, nothing else stalls.

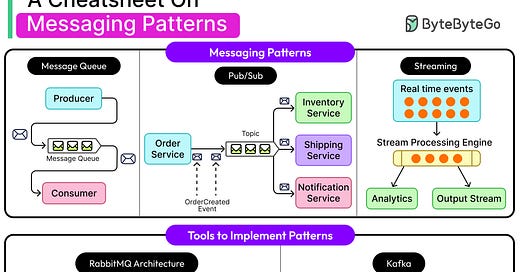

However, not all messaging systems look the same. Three main patterns show up frequently:

Message Queues: One producer, one consumer. Tasks get processed once and only once.

Publish-Subscribe: One producer, many consumers. Messages fan out to multiple subscribers.

Event Streams: A durable, replayable log of events. Consumers can rewind, catch up, or read in parallel.

Each pattern solves a different problem and comes with trade-offs in reliability, ordering, throughput, and complexity. And each maps to different real-world use cases, from task queues in background job systems to high-throughput clickstream analytics to real-time chat.

In this article, we will look at these patterns in more detail, along with some common technologies that help implement these patterns.

Core Concepts

Before we look at the patterns, let’s understand a few core concepts about messaging systems.

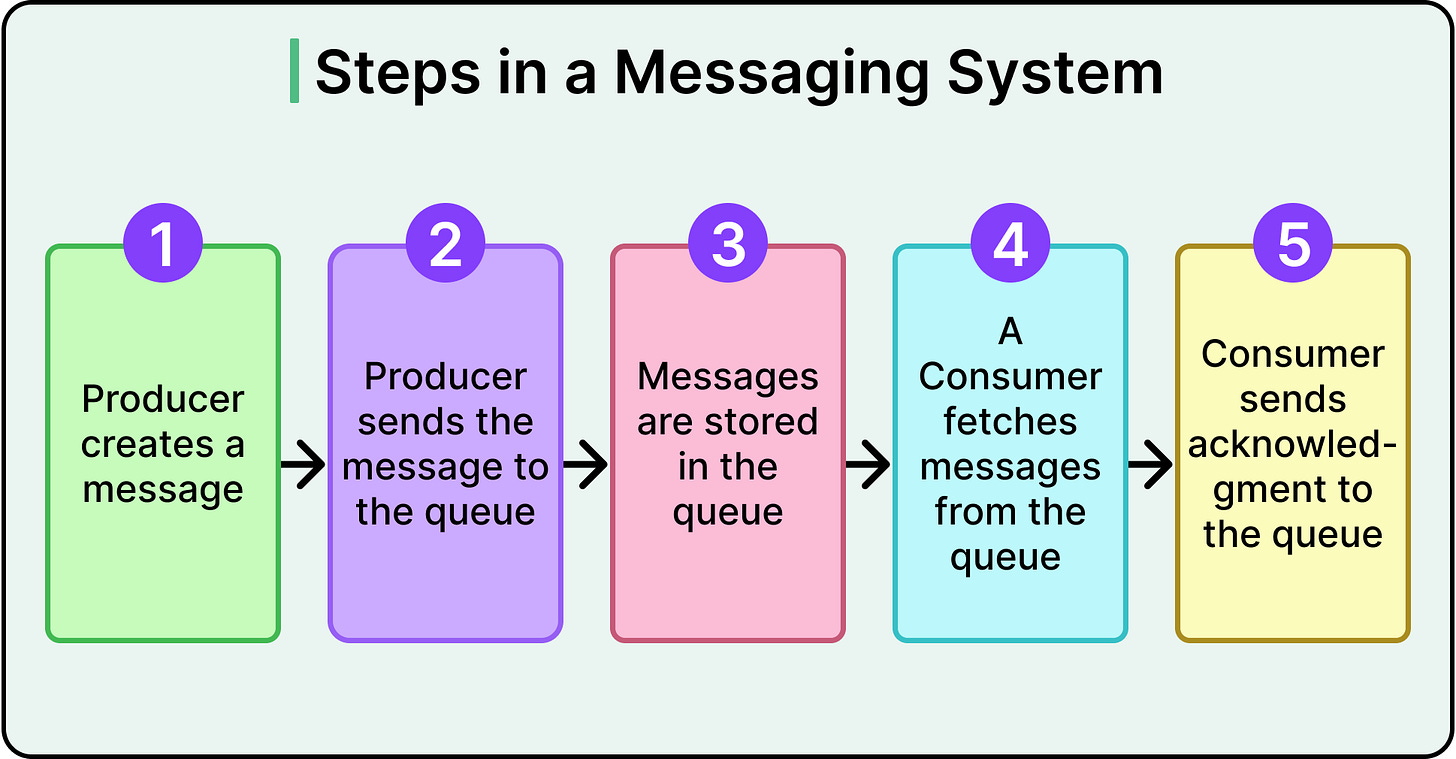

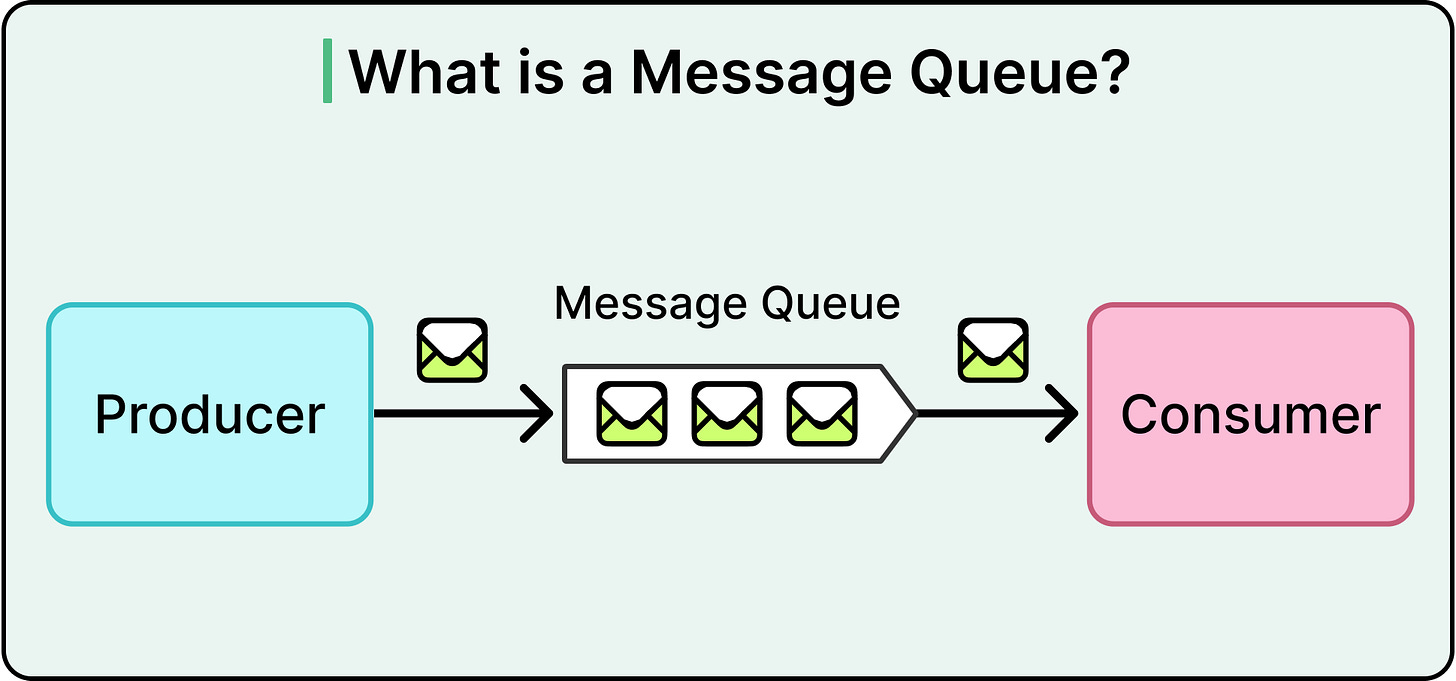

At its simplest, a messaging system moves information from one part of the system to another. A producer sends a message. A broker stores and routes it. A consumer picks it up and does something useful with it.

This pattern forms the backbone of event-driven systems, job queues, stream processors, and real-time notifications.

Producers, Consumers, and Brokers

A producer is any component that generates messages, usually by pushing data into a queue or topic. That might be a frontend service publishing user activity, or a backend service enqueueing a task for later.

A consumer pulls messages from the system and processes them. It might trigger a database write, send a notification, or kick off a background computation.

Sitting between them is the broker or the middleman responsible for receiving, storing, and delivering messages. Without the broker, producers and consumers are tightly coupled. With it, they’re decoupled, fault-tolerant, and able to scale independently.

Topics, Queues, and Partitions

Messages are usually organized into topics or queues, depending on the messaging model. A queue implies a single line of consumption: one consumer gets each message. A topic opens the door to multiple subscribers, where each gets their copy.

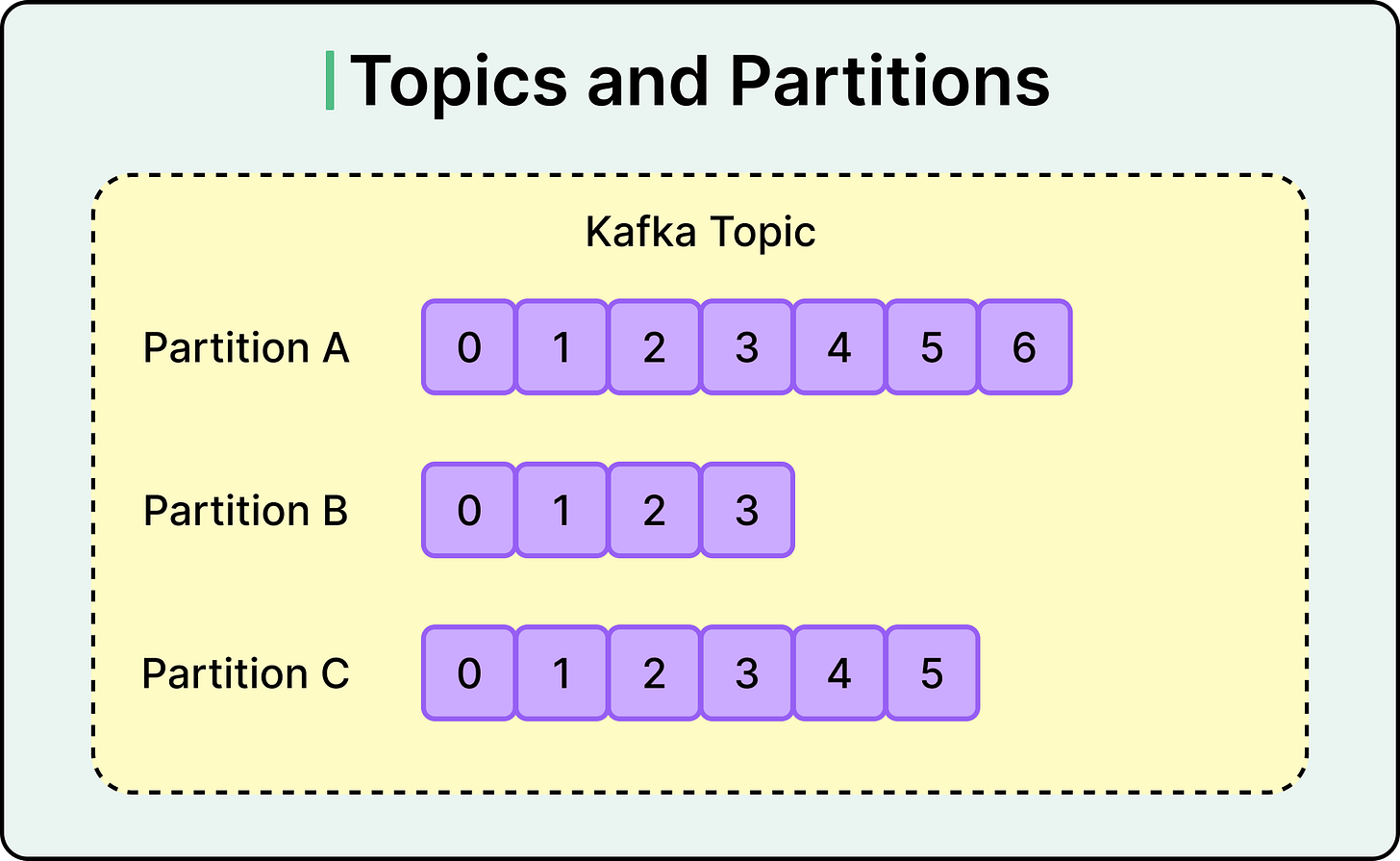

To scale processing, systems often divide topics into partitions. Each partition is an independent log, allowing multiple consumers to read in parallel. But partitioning introduces its trade-offs, especially around message ordering and load balancing.

Delivery Semantics: At-most-once, At-least-once, Exactly-once

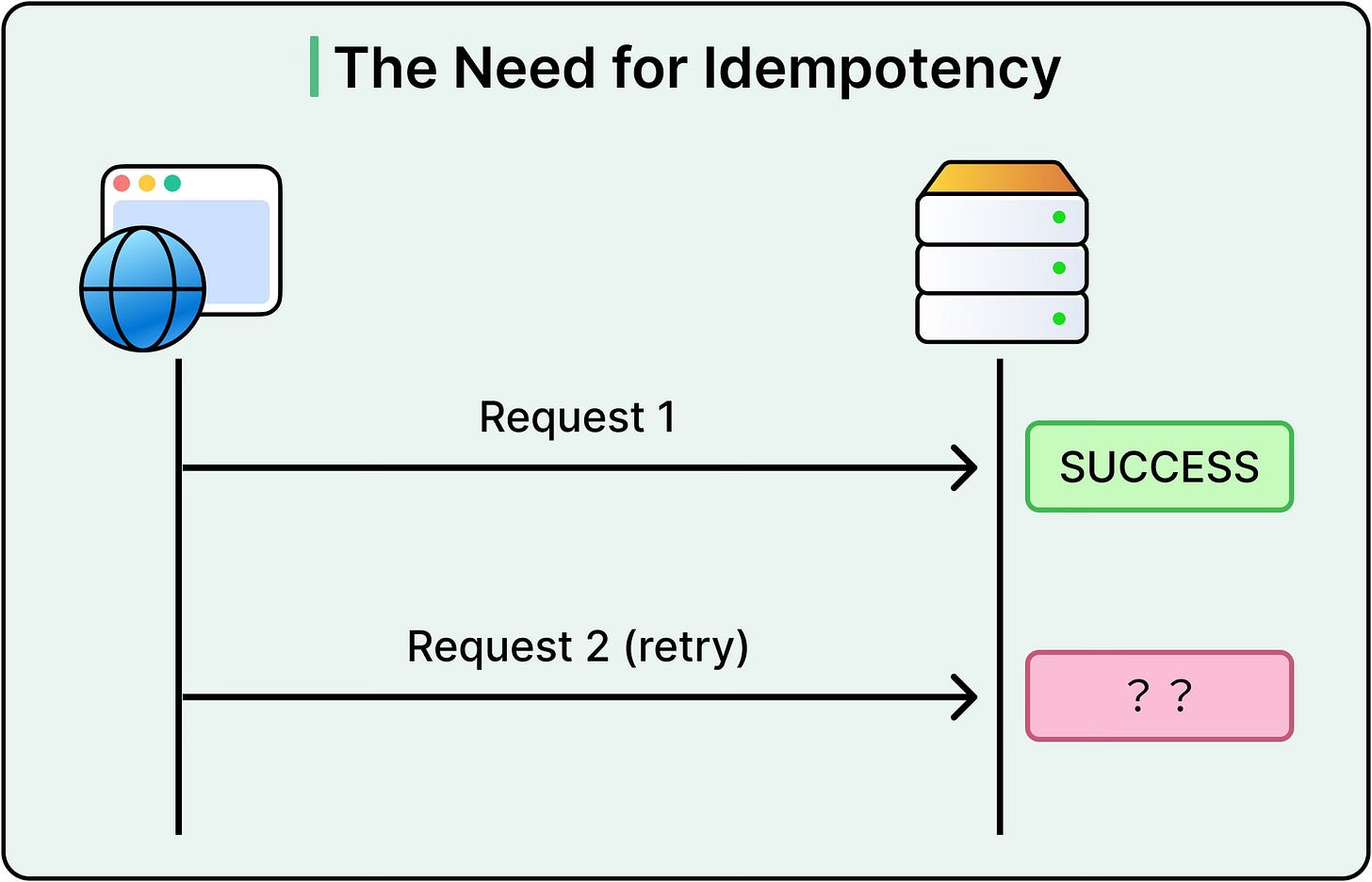

Not every message arrives the way it was sent. Network blips, service crashes, and retries all interfere. This leads to three critical delivery guarantees:

At-most-once: Messages are delivered once or not at all. There are no retries. This is a fast but risky approach

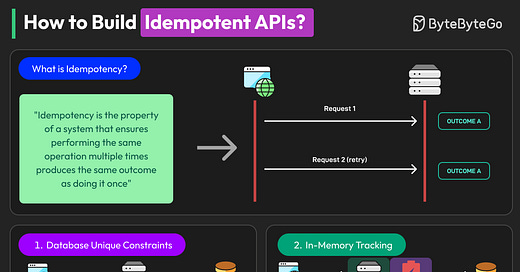

At-least-once: Messages are delivered one or more times. Retries happen, but duplicates are possible.

Exactly-once: Each message is delivered once and only once. The gold standard but the most challenging.

Most systems settle for at-least-once because it strikes a practical balance. Duplicates can be handled by making downstream operations idempotent. In other words, safe to run multiple times.

Messaging Queues

Consider a line at the airport counter. One person at the counter, one person being served, and everyone else waiting their turn. That’s the essence of a message queue: one producer drops a task into a line, and one consumer picks it up to process.

This model, called point-to-point messaging, powers some of the most critical infrastructure in backend systems. When a service needs to offload work, distribute tasks to workers, or decouple synchronous execution from downstream slowness, queues get the job done.

How Message Queues Work

A producer pushes messages into a queue. These messages typically represent discrete units of work: generate a PDF, resize an image, send an email, recalculate a user’s billing status.

A consumer pulls from the queue and processes each message. Once done, it can also provide an acknowledgment, telling the system that this message has been handled.

Key behaviors of message queues include:

Single consumption: Once a message is processed and acknowledged, it’s gone. No other consumer gets it.

FIFO (First-In, First-Out): Many queues aim for ordered processing, but in practice, ordering isn’t guaranteed unless explicitly configured.

Retries and redelivery: If a consumer crashes or fails mid-task, the system can retry the message after a timeout. This helps maintain reliability but introduces the risk of duplicate work unless the processing is idempotent.

Dead-letter queues (DLQs): If a message keeps failing after several attempts, it’s moved to a special queue for inspection. This avoids poison messages clogging the system.

Use Cases That Fit the Model

Message queues thrive in work distribution scenarios where each message represents a job that should be handled once and only once:

Background job processing: Queue up non-critical tasks (like sending emails) so the main request thread stays responsive.

Worker pools: Distribute tasks across multiple instances that pull from the same queue, scaling horizontally without coordination headaches.

Rate limiting or throttling: When downstream services have tight capacity constraints, queues can absorb bursts and smooth out the load.

Transactional systems: Ensure tasks are processed exactly once per event by isolating them and ensuring they complete before acknowledgment.

Think of queues as a shock absorber. They smooth out the bumps between fast producers and slower consumers, letting each side work at its own pace. But they also introduce latency and backlogs if left unchecked. Monitoring queue depth, message age, and processing time becomes critical in production.

Where Things Get Tricky

Here are a few things to keep in mind when using message queues.

Scaling consumers sounds easy: just add more workers. But ordering may break, and coordination becomes key.

Retries can flood a system with duplicate work if not properly delayed or deduplicated.

Stuck consumers can quietly hold up processing unless health checks and timeouts are enforced.

Publish Subscribe

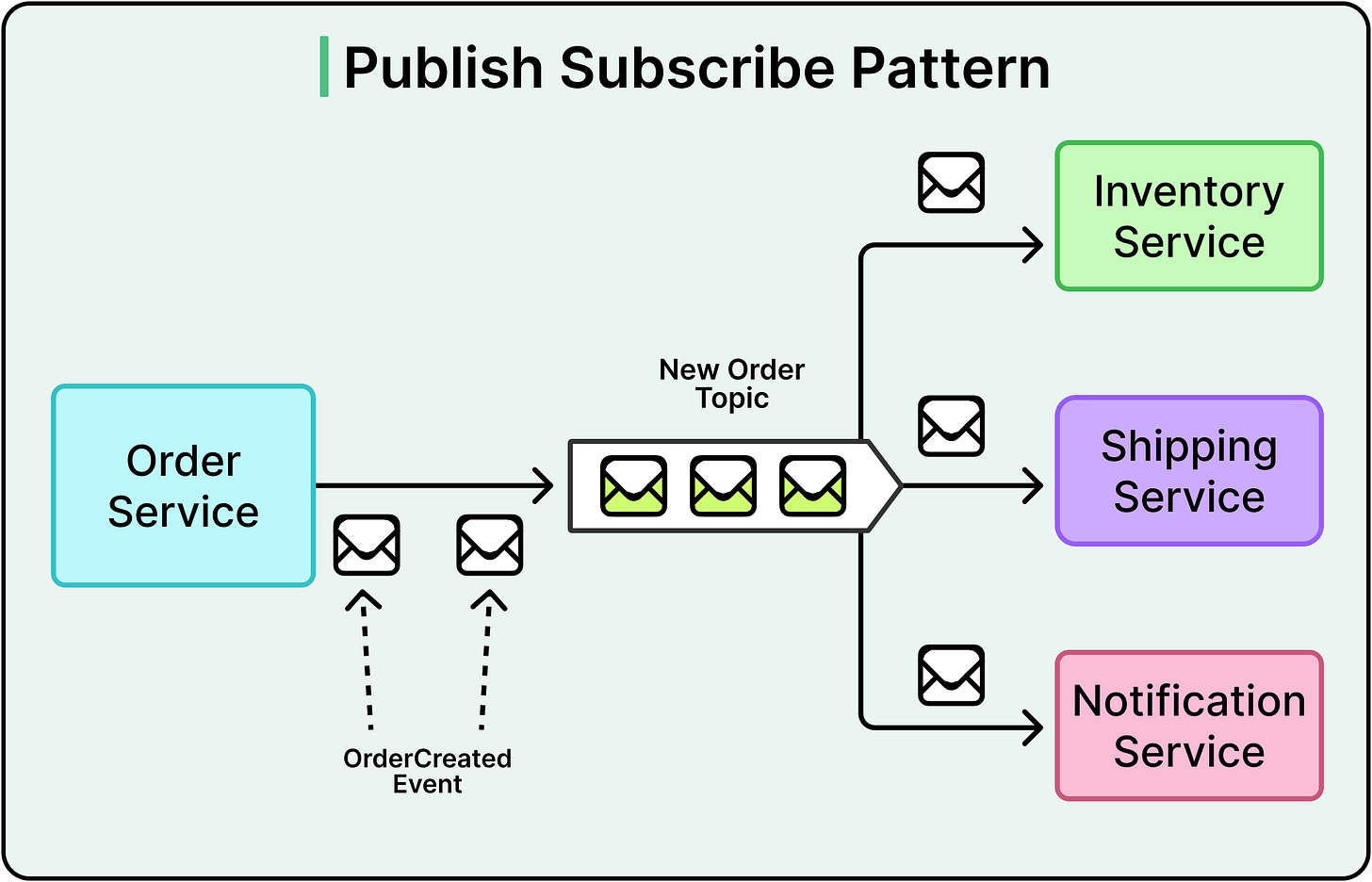

Imagine a news bulletin going live. It doesn’t matter if there’s one viewer or a million. Everyone subscriber gets the same message. That’s the essence of publish-subscribe (pub-sub) messaging: one message, many recipients.

Where message queues push a job to a single worker, pub-sub systems fan out messages to multiple independent subscribers. Each subscriber gets their copy and processes it at their own pace.

How Pub-Sub Works

A producer publishes a message to a topic. That topic acts like a broadcast channel. Any number of subscribers listening to the topic receive a copy of the message.

This pattern introduces two key benefits:

Decoupling: Publishers don’t know who’s listening.

Scalability: New consumers can be added without changing the producer or broker.

But pub-sub systems aren’t all the same. The way they manage subscriptions and deliver messages varies.

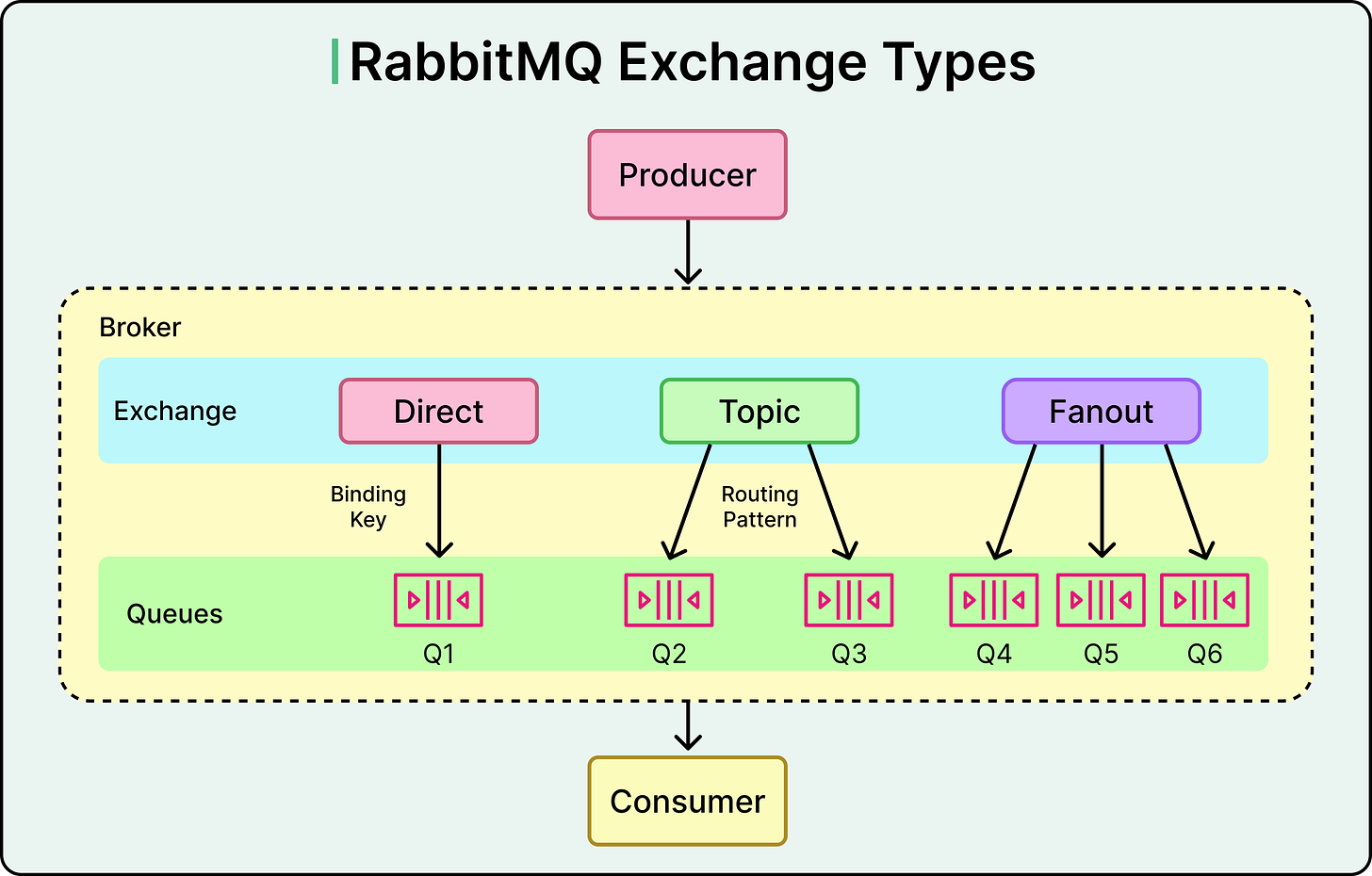

See the diagram below that shows an example:

Consumer Groups and Load Sharing

In some pub-sub systems (like Kafka or Pulsar), consumer groups allow messages to be shared among multiple consumers within a group, while still broadcasting to all groups. This adds a hybrid dimension:

Every group gets every message.

Within a group, consumers share the load, similar to a queue.

This pattern is common in large-scale systems where multiple services need the same data, but don’t want to process the full stream on a single machine.

Where Pub-Sub Fits

Pub-sub patterns are a natural fit when multiple systems care about the same event:

Event broadcasting: When a user uploads a photo, notifies friends, updates timelines, and logs the event, all triggered by the same publish.

Real-time updates: Financial tickers, sports scores, and collaborative editors rely on low-latency, fan-out delivery.

Notification systems: Send emails, push alerts, and in-app pings, each handled by a different subscriber.

Logging and telemetry: Push events to multiple sinks: Elasticsearch for search, S3 for archiving, Prometheus for metrics.

Common Challenges and Trade-Offs

Some common challenges with the pub-sub pattern are as follows:

Backpressure: If one subscriber lags, should the system slow down, buffer, or drop messages? This choice affects durability and latency.

Replayability: Not all pub-sub systems retain messages. Some only deliver in real-time.

Delivery guarantees: These vary wildly from at-most-once to exactly-once. Choosing the right broker and configuration matters.

Event Streams

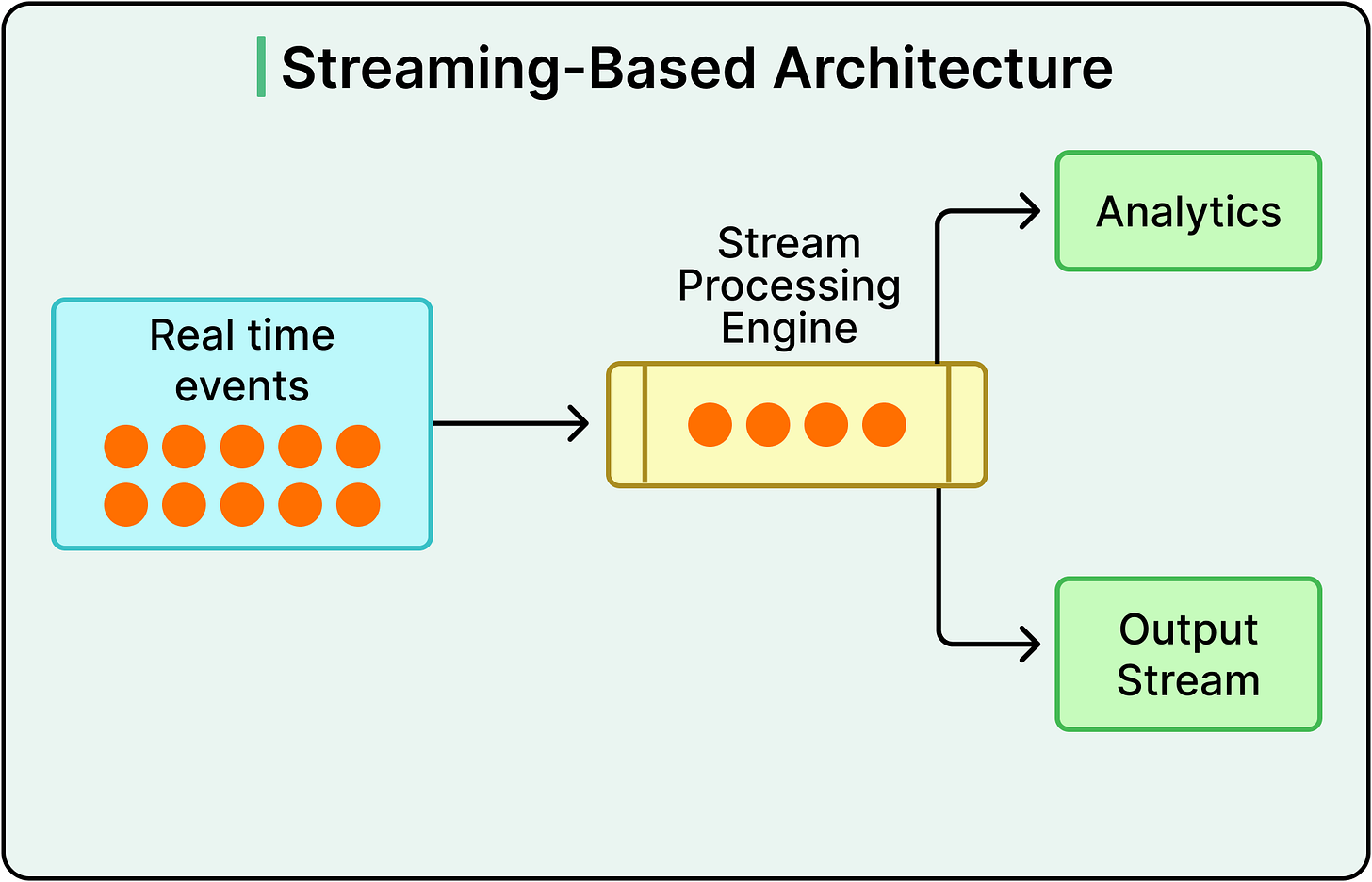

Picture a ledger with every transaction recorded and timestamped. That’s the core of an event stream: a durable, append-only log of what happened in the system, in the exact order it occurred. There are no overwrites or deletions.

Unlike queues or pub-sub, event streaming isn’t just about message delivery. It’s about retaining the entire history. Consumers don’t just get what’s happening now. They can go back and replay what happened before. This fundamentally shifts how systems store, process, and reason about data.

What Is an Event Stream?

An event stream is a chronological record of immutable events, written to a log-like structure by producers.

Each new event gets appended to the end of a partition, which preserves ordering within that stream. Events are not removed once consumed. Instead, they persist for a defined retention period (or indefinitely).

Consumers subscribe to the stream and maintain their offset as a marker of how far they’ve read. This lets different consumers move at different speeds, start from different positions, and even rewind for reprocessing.

This model enables a set of powerful features:

Replayability: Rewind to reprocess past data. Fix bugs, rebuild state, or feed new consumers.

Time-travel debugging: Trace exactly what happened and when. Pinpoint the sequence of events leading to a bug.

Data auditability: Keep a complete trail of business activity, ideal for compliance, analytics, and fraud detection.

Multiple independent consumers: Each system reads the log at its own pace without any need for coordination.

Comparing Patterns

No pattern wins in every situation. Each serves a different purpose, makes different trade-offs, and breaks down under different pressures. Understanding those trade-offs is what separates brittle systems from ones that adapt.

Here’s how the three core patterns compare across six critical dimensions:

Delivery Model

Message Queues follow a point-to-point model. One producer, one consumer. Once a message is acknowledged, it's gone.

Pub-Sub follows a one-to-many model. One message is broadcast to multiple subscribers. Each receives and processes its copy.

Event Streams also support one-to-many, but with a key difference: consumers don’t get their copy temporarily. They read from a shared, durable log at their own pace.

Ordering Guarantees

Queues often aim for FIFO delivery, but that guarantee may break under retries. Ordering is per queue but not globally consistent.

Pub-Sub typically offers no global ordering across subscribers. Some systems (like Google Pub/Sub) may preserve ordering within specific keys or subscriptions, but it’s not the default.

Event Streams preserve strong ordering within each partition. This is critical for systems that need deterministic replay or consistent state reconstruction.

Replayability

Queues discard messages once acknowledged. Replay isn’t possible without external storage or logging.

Pub-Sub behavior depends on the broker. Some implementations (such as Redis Pub/Sub) offer no retention, while others (such as Pulsar, NATS JetStream) support limited replay with durable subscriptions.

Event Streams offer first-class replayability. Consumers can rewind to a specific offset or timestamp and reprocess data as needed, making them ideal for bug recovery, state rebuilding, and backfills.

Latency and Throughput

Queues typically have low latency, especially with a single fast consumer. Throughput scales with the number of parallel consumers, up to the limit of ordering guarantees.

Pub-Sub can offer low latency and moderate throughput, but large fan-out or slow subscribers may introduce head-of-line blocking or backpressure.

Event Streams optimize for high throughput, often in the millions of messages per second. Latency may be higher depending on buffering, batching, and partitioning.

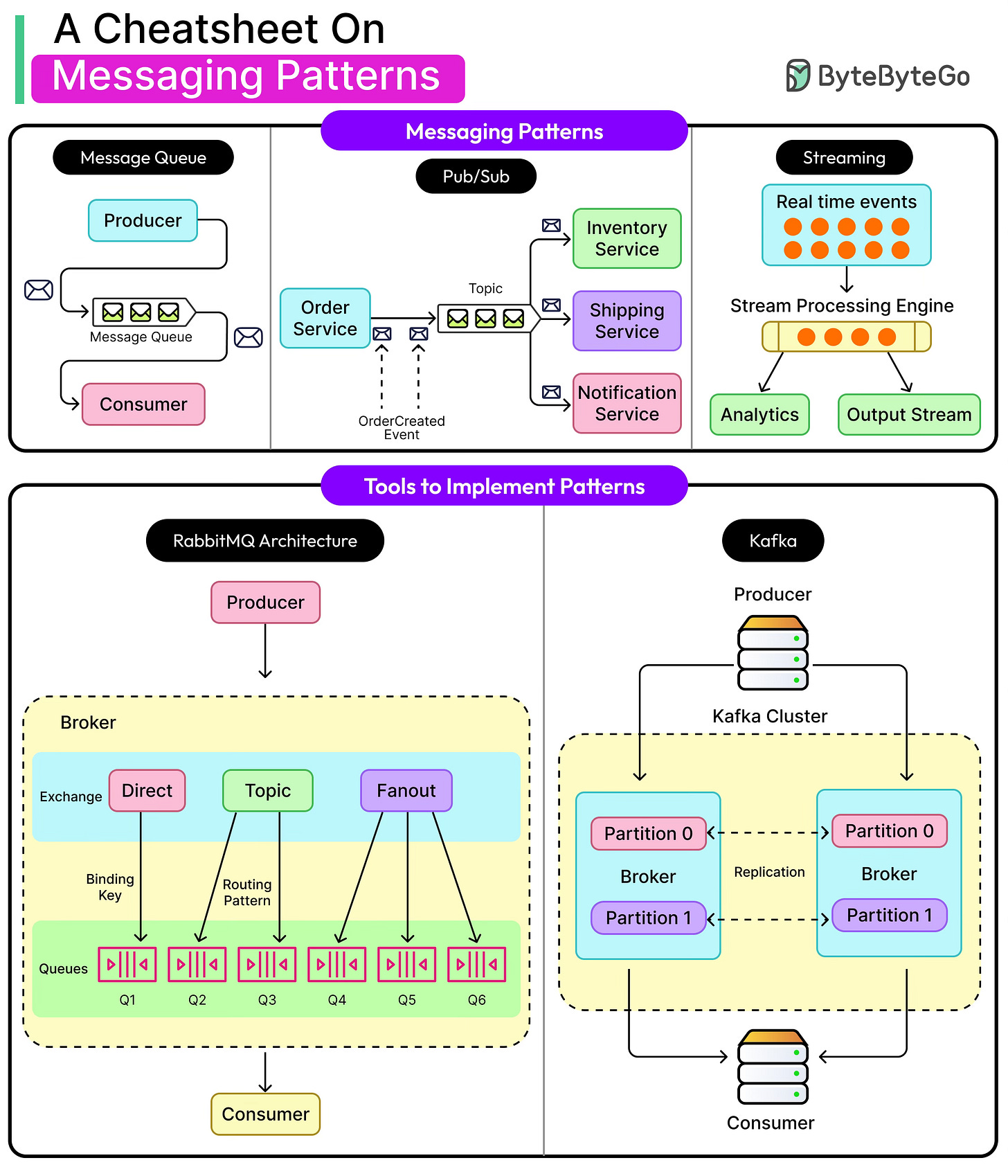

Deep Dive: Kafka and RabbitMQ

No messaging pattern exists in a vacuum, and neither do tools. Each tool comes with its design philosophy, operational quirks, and architectural sweet spots. Choosing between tools like Kafka or RabbitMQ is about understanding what each one optimizes for and what it expects from the system around it.

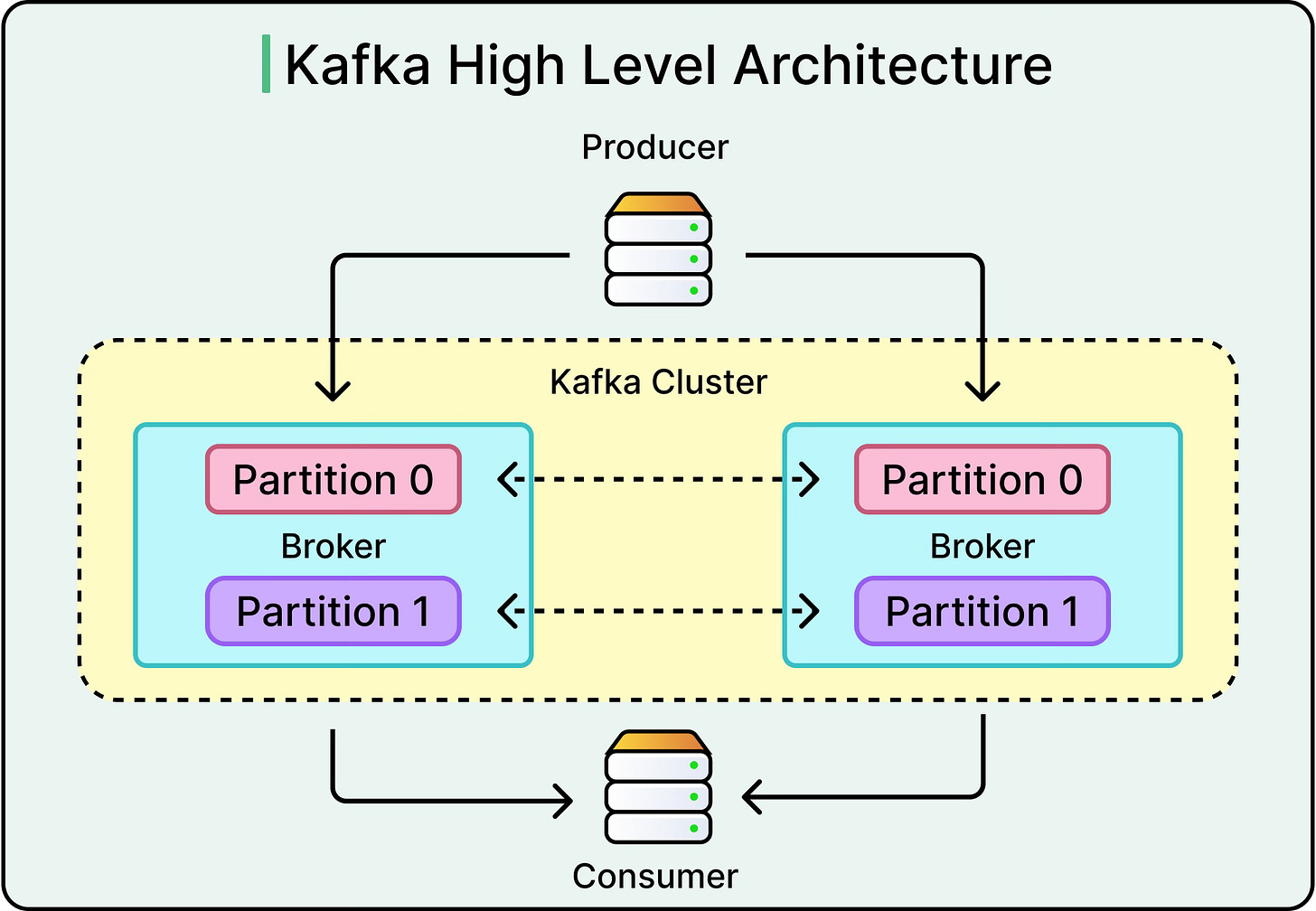

Apache Kafka

Kafka is more than a messaging system. It’s a durable, distributed log built for high-throughput, scalable, and replayable event streaming. Originally developed at LinkedIn, Kafka treats events as first-class citizens and emphasizes immutability, order, and persistence.

Key characteristics are as follows:

Partitioned logs: Topics are divided into partitions, each an ordered, append-only log. This enables horizontal scaling and high read/write throughput.

Offset-based consumption: Consumers track their position in the log, enabling replay, backfill, and time-based consumption.

Built-in durability: Messages are persisted to disk and replicated across brokers. Data can be retained for hours, weeks, or forever.

High throughput: Kafka handles millions of messages per second. It’s used heavily in telemetry, metrics pipelines, and clickstream analytics.

Core use cases of Kafka are as follows:

Change data capture (CDC)

Real-time stream processing with Kafka Streams or Flink

Audit logs and operational telemetry

RabbitMQ

RabbitMQ is a battle-tested, general-purpose message broker rooted in traditional queueing semantics. It implements the AMQP protocol, giving it rich capabilities around routing, acknowledgement, and delivery guarantees.

Key characteristics of RabbitMQ are as follows:

Queue-first design: Messages are stored in queues and consumed once. Durable queues and acknowledgments protect against data loss.

Routing flexibility: Offers exchanges (direct, fanout, topic, headers) to support complex message routing logic.

Protocol support: Works out-of-the-box with AMQP, MQTT, STOMP, and more—great for integrating with legacy systems.

Low latency: Lightweight, fast, and great for task dispatching and synchronous workflows.

The core use cases of RabbitMQ are as follows:

Transactional systems that need strict ordering.

Worker queues and task orchestration.

Pub-sub over short-lived connections.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at messaging patterns in detail, along with their suitability in various scenarios.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Messaging systems decouple services and absorb failures, making them essential for building scalable, resilient architectures in distributed environments.

Message queues follow a point-to-point model, ideal for background job processing, worker pools, and task delegation, where each message is processed once by one consumer.

Publish-subscribe enables one-to-many communication, allowing multiple consumers to independently react to the same message. It is useful for real-time updates, alerts, and distributed state changes.

Event streams offer durable, ordered, and replayable logs of events, empowering systems to rebuild state, audit activity, and run large-scale stream processing pipelines.

Queues emphasize reliability over speed, working best when latency is less important than guaranteed task completion and load smoothing.

Pub-sub reduces tight coupling across systems and enables scalable fan-out, especially in environments where producers shouldn’t know who’s consuming the data.

Event streams are the backbone of event-driven architectures where high throughput, history, and state reconstruction matter more than low latency or simple delivery.

Apache Kafka is a high-throughput, partitioned log system optimized for event streaming, best suited for analytics, telemetry, and replay-heavy architectures.

RabbitMQ is a flexible message broker with strong queuing and routing capabilities, ideal for transactional tasks, job queues, and legacy protocol support.

Apache Pulsar offers a hybrid model supporting both streaming and queuing, with tiered storage, geo-replication, and multi-tenancy built for cloud-native platforms.