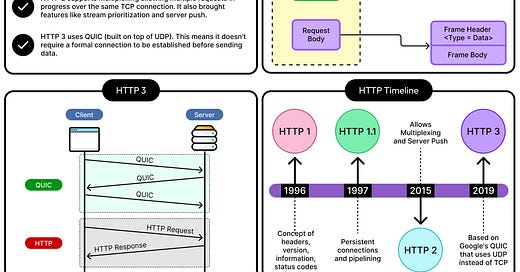

HTTP is the backbone of modern internet communication, powering everything from browser requests to microservices inside Kubernetes clusters.

Every time a browser loads a page, every time an app fetches an API response, every time a backend service queries another, it’s almost always over HTTP. That’s true even when the underlying transport changes. gRPC, for example, wraps itself around HTTP/2. RESTful APIs, which dominate backend design, are just a convention built on top of HTTP verbs and status codes. CDNs, caches, proxies, and gateways optimize around HTTP behavior.

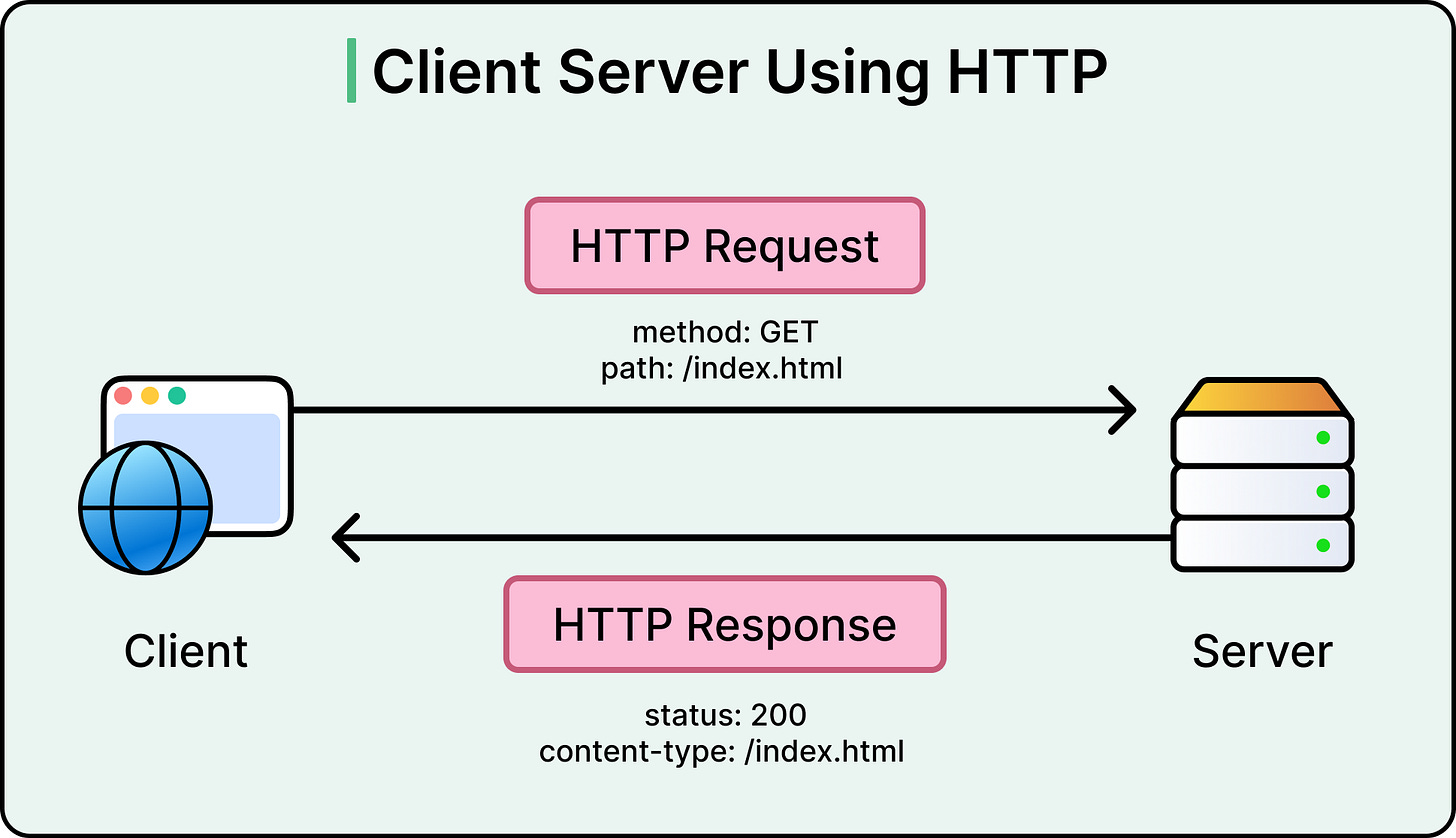

Understanding HTTP is less about memorizing status codes and more about internalizing the performance trade-offs baked into the protocol’s evolution. HTTP/1.0 opened the door. HTTP/1.1 made it usable at scale. HTTP/2 pushed efficiency by multiplexing streams over a single TCP connection. And HTTP/3, built on QUIC over UDP, finally breaks free from decades-old constraints.

In this article, we trace that journey. From the stateless, text-based simplicity of HTTP/1.1 to the encrypted, multiplexed, and mobile-optimized world of HTTP/3.

Along the way, we’ll look at various important aspects of HTTP:

How does TCP’s design influence HTTP performance, especially in high-latency environments?

Why does head-of-line (HOL) blocking become a problem at high scale?

How do features like header compression, server push, and connection reuse change the performance game?

And where does HTTP/3 shine and still face issues?

HTTP/1.1 - The Workhorse

HTTP/1.1 was introduced in 1997. It took the barebones approach of HTTP/1.0 and added just enough muscle to support the explosive growth of the internet in the early 2000s. Most of today’s HTTP clients and servers still default to HTTP/1.1 if nothing more modern is available.

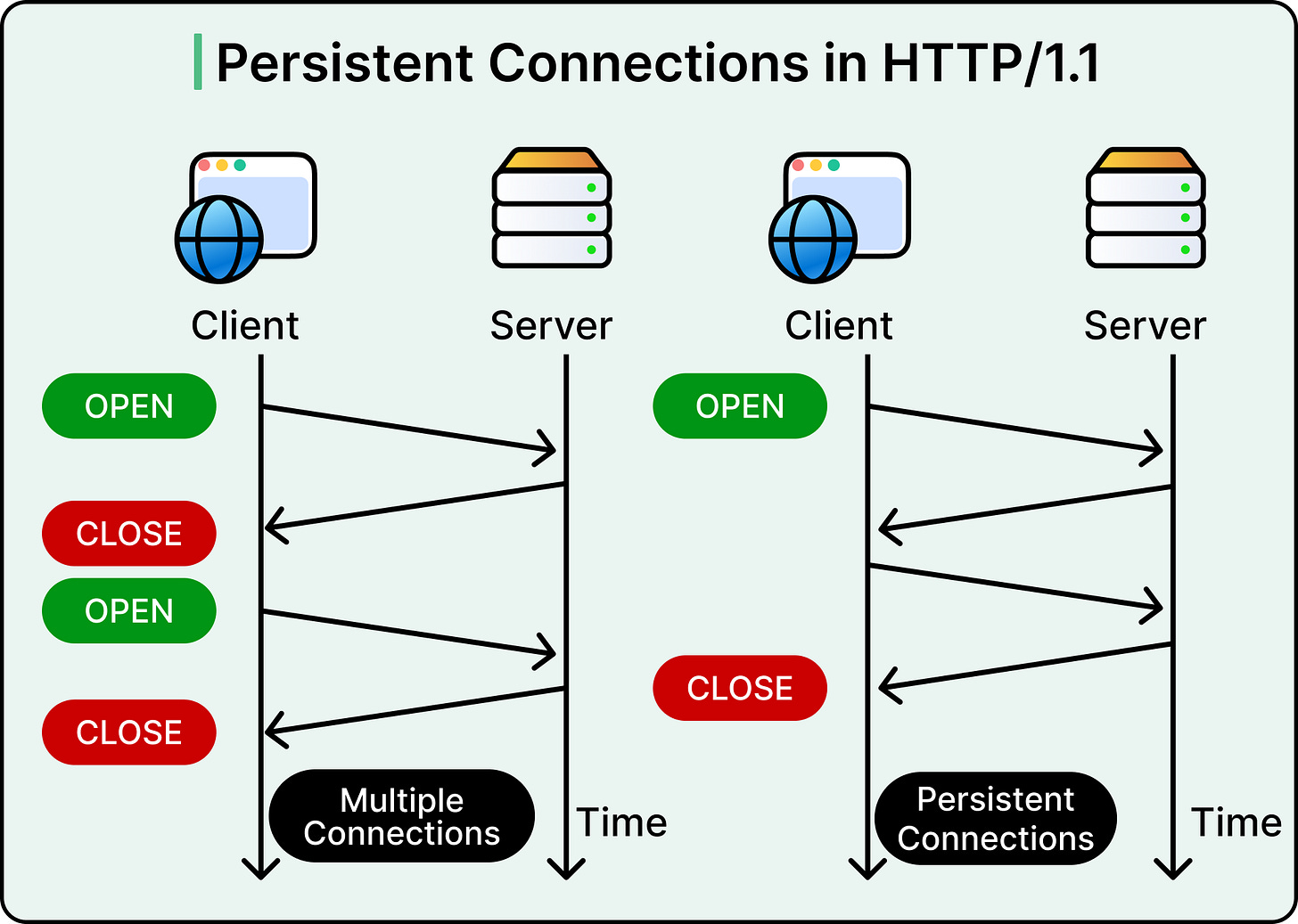

The most important shift in HTTP/1.1 was the support for persistent connections. In HTTP/1.0, every request opened a new TCP connection, which is a costly and slow operation. HTTP/1.1 introduced “Connection: keep-alive”, which allowed multiple requests and responses to travel over the same TCP connection without reopening the socket every time. This single feature dramatically reduced latency and network overhead for web pages that needed dozens of assets.

Other critical upgrades followed:

Chunked Transfer Encoding allowed servers to begin sending responses before knowing the final content length, enabling streaming and more responsive apps.

Host headers enabled virtual hosting, which lets multiple domains share the same IP address.

Content negotiation allowed servers to serve different versions of the same resource (for example, language, encoding) based on client headers.

Improved caching directives like Cache-Control, ETag, and Last-Modified helped both browsers and intermediate proxies make smarter decisions about what to reuse.

Range requests made it possible to fetch partial content. This is useful for video streaming, resumable downloads, and media-heavy applications.

However, for all its improvements, HTTP/1.1 remained constrained by its transport layer.

Where Things Start to Break?

At its core, HTTP/1.1 uses TCP: a reliable, ordered protocol. That reliability comes at a price.

First, head-of-line (HOL) blocking became a structural problem. TCP ensures that packets arrive in order, which means that if a single packet is delayed or lost, everything behind it must wait, even if it belongs to a different HTTP request. In HTTP/1.1, this gets worse because there’s no native way to interleave multiple requests within a single connection.

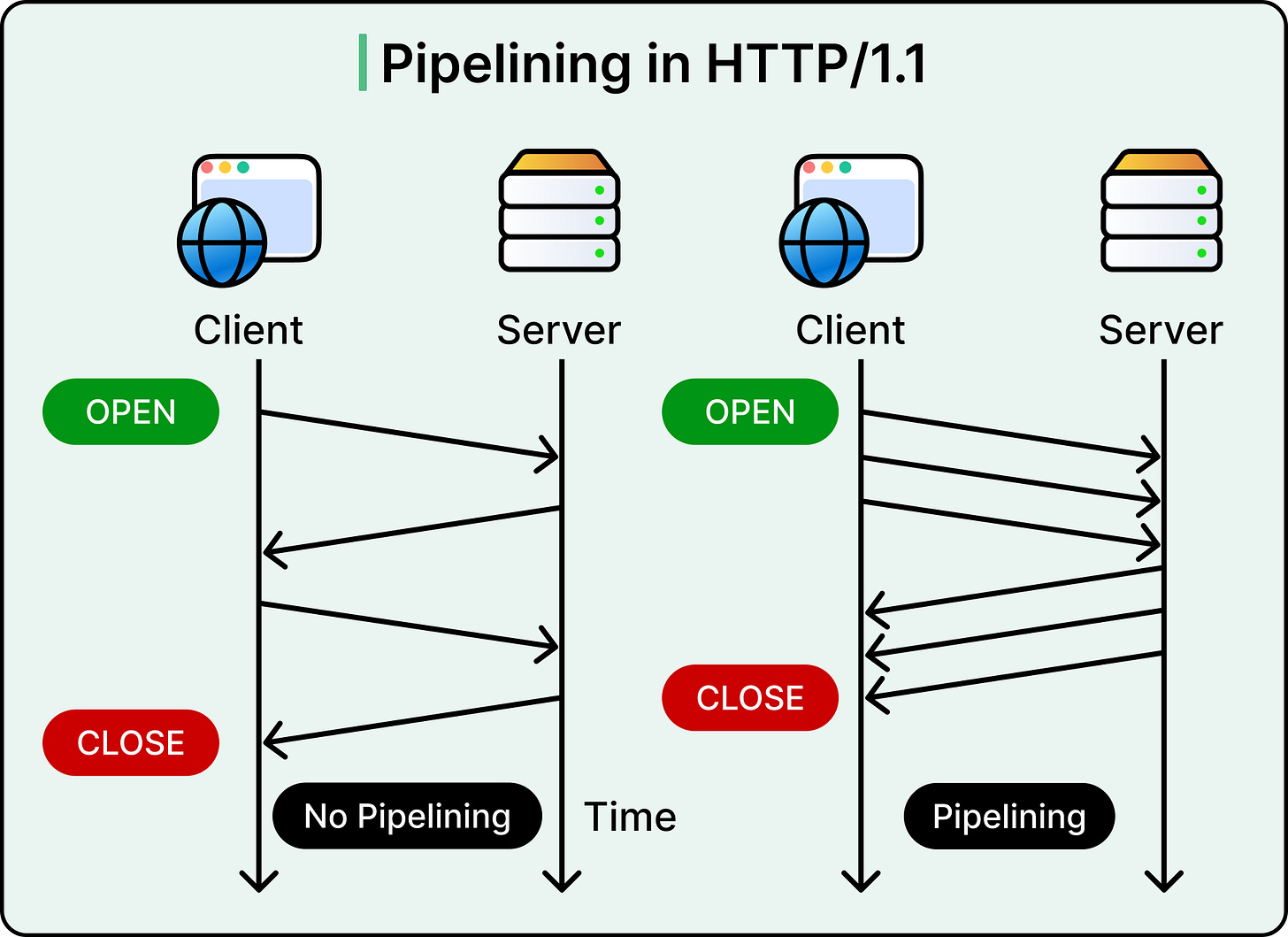

Without pipelining, only one request at a time can be in flight per connection. The client must wait for a response before sending the next request. Browsers worked around this by opening multiple simultaneous connections per origin (usually 6 to 8), but that adds overhead on both client and server.

HTTP/1.1 did support pipelining, where clients could send multiple requests without waiting for responses. However, due to inconsistent server support and response reordering issues, most clients disabled it. In practice, pipelining never saw real adoption.

As web pages grew more complex (loading hundreds of assets including fonts, CSS, JavaScript, and images) HTTP/1.1 started to feel like a bottleneck. Engineers began reaching for workarounds such as:

Image sprites that combine multiple icons into one file to reduce request count.

Concatenation of JS and CSS into fewer files to avoid connection limits.

Domain sharding that spreads assets across subdomains to trick browsers into opening more parallel connections.

Each workaround improved throughput but added maintenance overhead and complexity. And none of them addressed the root issue: HTTP/1.1’s inability to efficiently handle concurrent requests at scale.

The Role of TCP

To understand where HTTP/1.x struggles, it’s necessary to look one layer down: at TCP, the transport protocol it depends on. TCP guarantees ordered, reliable delivery, which is great for correctness but introduces fundamental performance costs that ripple upward into every HTTP request.

Every new TCP connection starts with a three-way handshake:

The client sends a SYN packet to initiate the connection.

The server replies with a SYN-ACK.

The client responds with an ACK, completing the setup.

Only after this handshake completes can actual data flow. On fast, local networks, this round-trip may feel negligible. However, over cellular or global connections, even this brief handshake introduces noticeable delay.

If the connection uses HTTPS, which it increasingly does these days, there's another handshake (TLS negotiation) layered on top that often adds one or two additional round-trips before any HTTP data moves. So, with HTTP/1.0 or non-persistent HTTP/1.1, each request potentially triggers multiple network round-trips before the application payload is even touched.

TCP also comes with a built-in safety mechanism: congestion control. It doesn't trust the network immediately. Instead, it starts by sending a small amount of data and then gradually ramps up as acknowledgments come back successfully. This is called a slow start.

The intent is to avoid overwhelming congested networks. But in practice, it penalizes short-lived connections. If a request completes before the congestion window expands, bandwidth goes unused. This becomes especially problematic for assets like JSON APIs or small images that don’t stick around long enough to benefit from the ramp-up.

HTTP/2 - Multiplexing to the Rescue

By the mid-2010s, HTTP/1.1 was showing its age. Websites had grown into sprawling applications, routinely pulling in hundreds of resources. Frontend teams pushed for richer user experiences. Mobile usage surged. But the protocol still forced every request through a narrow, serialized path, often throttled by TCP limitations.

HTTP/2, standardized in 2015, emerged as a direct response to these problems. It didn’t rewrite the semantics of HTTP. Verbs like GET, POST, PUT, and response codes like 200 OK remained the same. What changed was how data was transferred.

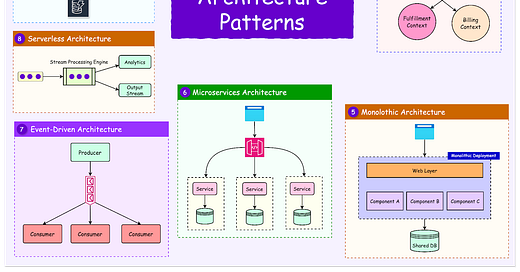

Binary Framing and Multiplexed Streams

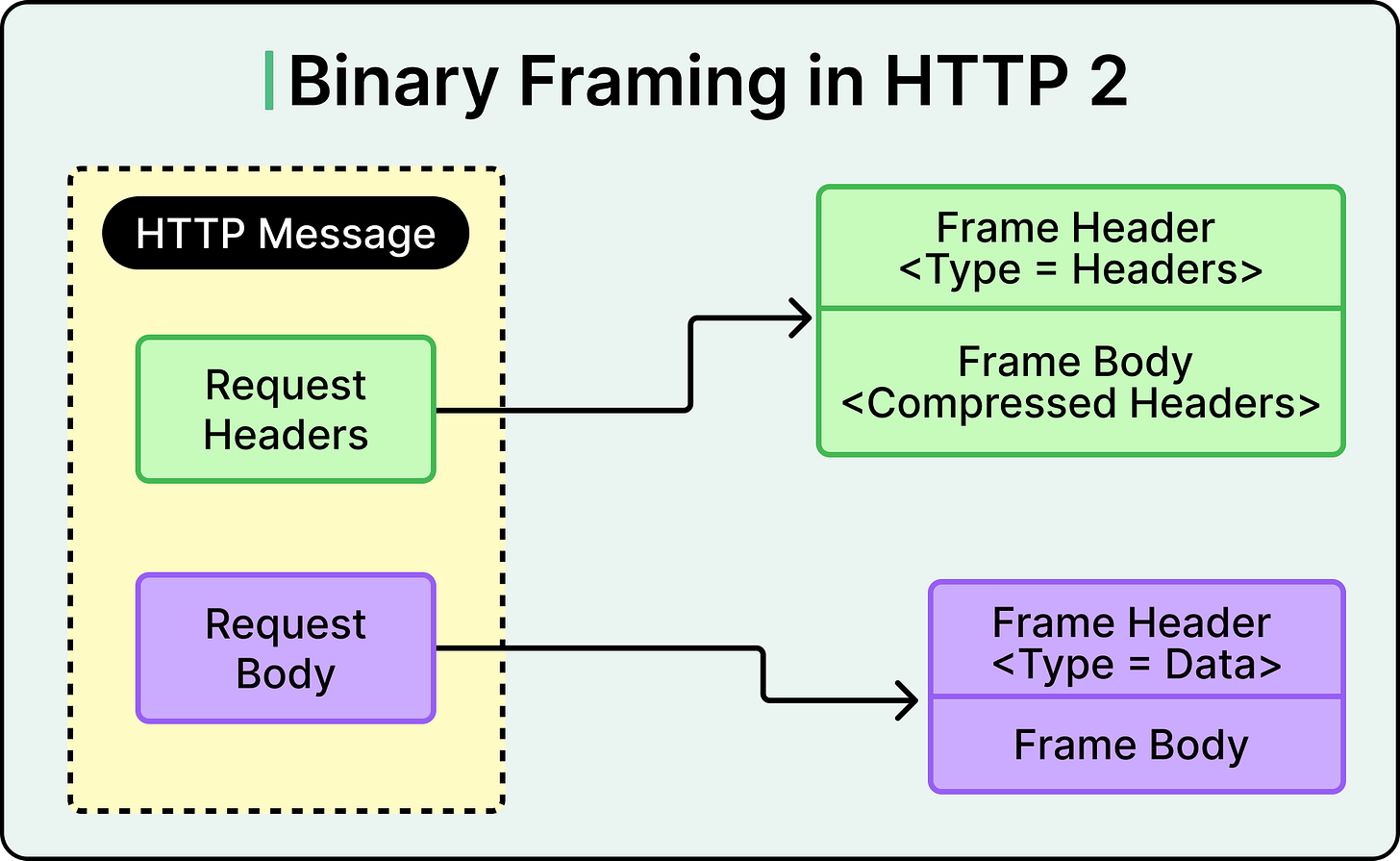

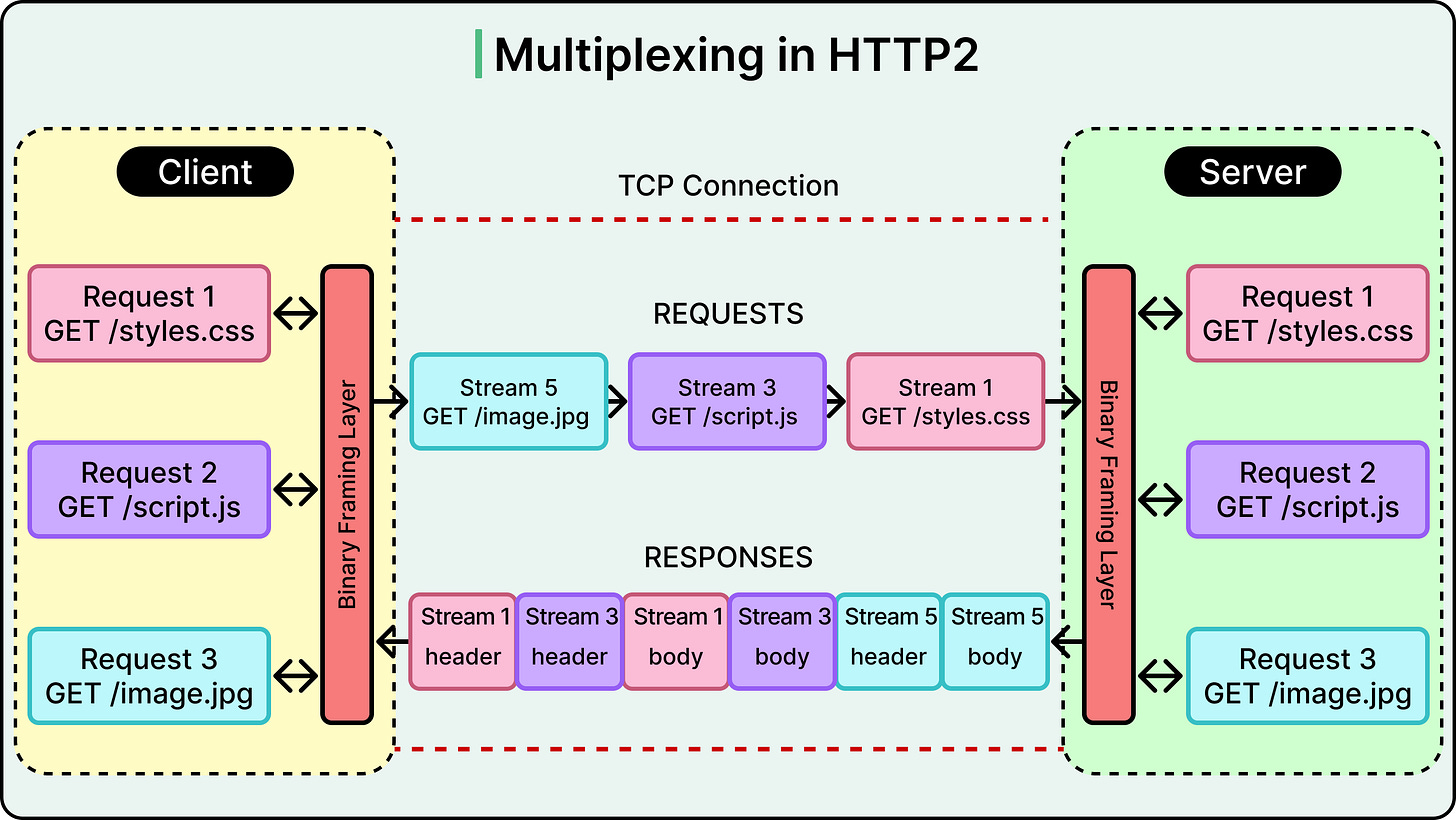

The most fundamental shift was HTTP/2 replacing the textual, line-by-line format of HTTP/1.x with a binary framing layer. Instead of parsing human-readable strings like Content-Type: application/json, HTTP/2 breaks all data into compact, structured binary frames. These frames are assigne independent streams, each with its ID.

This means a client can now open a single TCP connection to a server and send multiple requests concurrently, multiplexed over one connection. No more waiting for one request to finish before starting the next. The client sends frames from many streams interleaved, and the server responds the same way. The result is smoother parallelism and better network utilization.

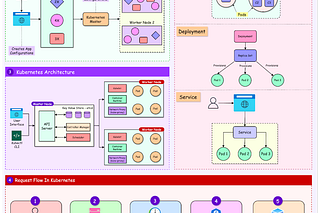

See the diagram below:

Beyond multiplexing, HTTP/2 introduced several performance upgrades

HPACK Header Compression: In HTTP/1.1, every request repeated headers like User-Agent, Accept-Encoding, and cookies, wasting bandwidth. HPACK eliminates this by using indexed compression. The client and server maintain synchronized tables of header values, and instead of resending them, they reference the table. This reduces header bloat significantly, especially when making repetitive API calls.

Stream Prioritization: Each stream can carry weight and dependency information, allowing the client to signal what matters most. For example, a browser can prioritize visible images over analytics scripts or preload fonts before below-the-fold assets.

Server Push: With HTTP/2, the server can preemptively send resources it knows the client will need (for example, CSS or JS files tied to an HTML page) before the browser explicitly asks. This avoids an extra round-trip and can speed up initial loads. However, in practice, server push adoption remains limited due to cache coordination issues and a lack of browser-level control.

The TCP Bottleneck Remains

Multiplexing solved the application-layer head-of-line (HOL) blocking that plagued HTTP/1.1. But it couldn’t escape TCP’s underlying limitations.

All streams still funnel through a single TCP connection. If a packet is lost, TCP’s reliability guarantee kicks in: everything after the missing packet must wait, regardless of which stream it belongs to. This means that a dropped packet for a low-priority image can still stall a high-priority API response, because the packet loss affects the entire connection.

This is transport-level HOL blocking, and it’s invisible to the application. From the browser or client’s perspective, everything takes a pause. In high-latency or lossy environments (like mobile networks or cross-continent traffic), this can turn into real pain: increased latency, jittery performance, or stalled loads despite otherwise efficient multiplexing logic.

So while HTTP/2 dramatically improved performance over HTTP/1.1 in controlled or wired networks, its architecture still tied concurrency to a single, ordered stream of TCP packets.

HTTP/3 and the Rise of QUIC

As mentioned, HTTP/2 fixed many of the inefficiencies in HTTP/1.1, but it hit a hard wall: TCP itself. No amount of multiplexing at the HTTP layer could avoid the core issue of head-of-line blocking at the transport level. As long as everything ran over TCP, a single lost packet would stall the entire connection.

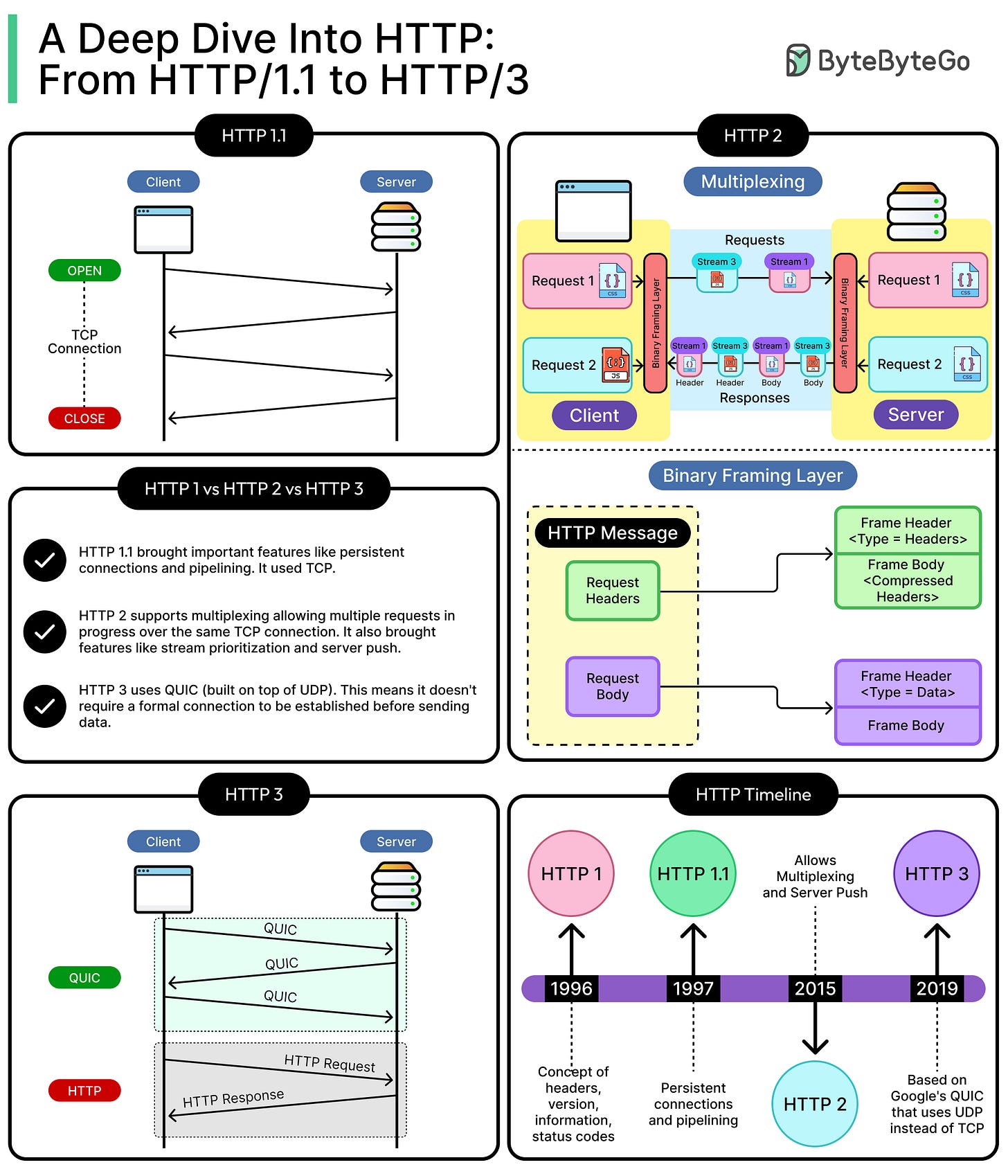

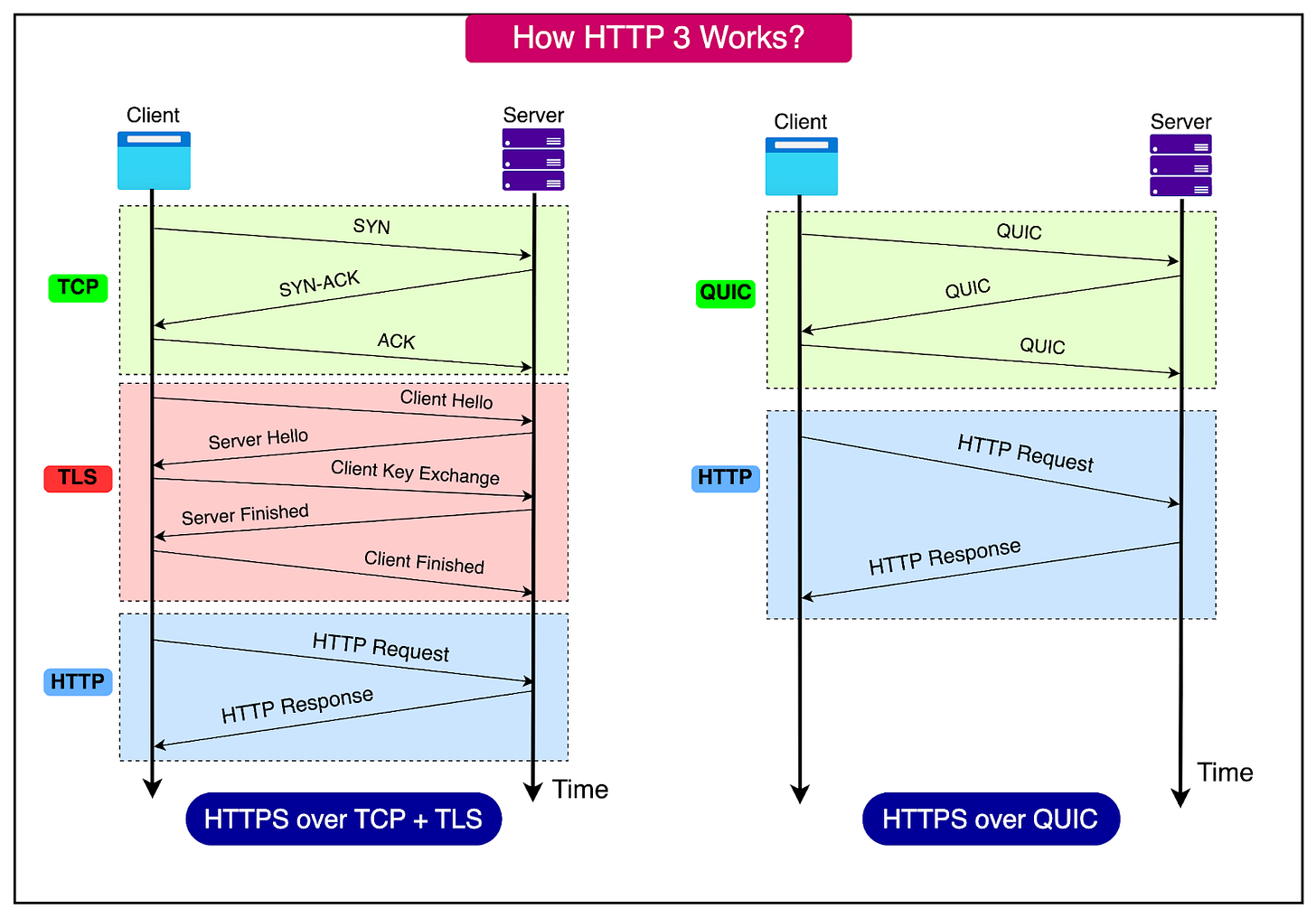

HTTP/3 breaks that pattern. It doesn’t just evolve HTTP but rides on an entirely different transport protocol: QUIC (Quick UDP Internet Connections), a UDP-based, encrypted-by-default alternative to TCP. Originally developed by Google and later standardized by the IETF, QUIC is designed to give HTTP the concurrency, reliability, and performance it always needed.

See the diagram below that shows how HTTP/3 works:

Multiplexing at the Transport Layer

The most critical shift in HTTP/3 is where multiplexing happens. HTTP/2 multiplexes streams at the application layer, but they still pass through a single ordered TCP connection. HTTP/3, by using QUIC, moves multiplexing down to the transport level.

Each stream in HTTP/3 is independent, not just logically, but physically. Packet loss on one stream doesn’t affect the others. There’s no head-of-line blocking across streams. This makes a major difference on high-latency or lossy networks like mobile and Wi-Fi.

Faster Connection Setup with 0-RTT

HTTP/3 reduces connection overhead by supporting 0-RTT (Zero Round-Trip Time) handshakes. Clients can start sending data during the first flight of packets, assuming the server has been contacted before. This optimization is especially impactful in latency-sensitive apps, where even 100ms matters.

Compare this to HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2, where a full TCP + TLS handshake might consume two or three round-trips before any request can even begin. QUIC collapses that process into one, or in some cases zero, making everything feel snappier, especially under HTTPS, which is mandatory for HTTP/3.

Built-In TLS 1.3 and Encryption by Default

QUIC integrates TLS 1.3 directly into the protocol stack. Unlike previous versions of HTTP, where TLS sat on top of TCP, HTTP/3 treats encryption as a built-in primitive. Every connection is encrypted. There’s no such thing as "unencrypted HTTP/3."

This simplifies implementation logic, avoids awkward layering issues, and makes security the baseline. It also ensures that features like 0-RTT are natively compatible with modern cryptographic standards.

Stream-Level Independence and Loss Recovery

Each stream in QUIC has independent flow control and retransmission logic. Packet loss no longer derails unrelated streams, and the protocol can recover more gracefully. QUIC’s internal acknowledgment and congestion control mechanisms mirror TCP’s in spirit but improve them in practice.

The result is a better utilization of bandwidth, lower tail latency, and more consistent performance across varying network conditions.

The Deployment Gap

Despite the benefits, QUIC adoption is still catching up. It uses UDP, which historically hasn’t played well with middleboxes (routers, firewalls, NAT devices) that expect predictable TCP flows.

Widespread adoption also requires upgrades across the stack:

Servers need to support QUIC at the transport layer (for example, via Envoy, NGINX, or custom implementations).

Clients, especially browsers and mobile apps, need QUIC-capable libraries.

CDNs and edge providers must handle QUIC’s different performance characteristics.

That said, major players have already crossed that bridge. Google services, YouTube, Facebook, and Cloudflare all serve traffic over HTTP/3 at scale. Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and most modern browsers support it. The infrastructure is rapidly catching up.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at the HTTP protocol in great detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

HTTP remains foundational to modern internet systems—understanding its evolution helps debug performance issues, optimize APIs, and build resilient architectures.

HTTP/1.0 introduced basic request-response semantics but lacked persistence, making it inefficient for multi-asset pages.

HTTP/1.1 added persistent connections with keep-alive, chunked transfer encoding, host headers, and caching features, significantly improving web performance.

Despite improvements, HTTP/1.1 suffered from TCP-level limitations, especially head-of-line (HOL) blocking and one-request-at-a-time constraints.

TCP's three-way handshake and TLS setup introduce latency, particularly on high-latency or encrypted connections.

TCP’s congestion control and slow start mechanisms penalize short-lived connections and limit throughput early in a session.

HTTP/2 introduced a binary framing layer and allowed multiplexing of many requests over a single TCP connection, significantly improving concurrency and efficiency.

HPACK compression in HTTP/2 reduced redundant headers, improving bandwidth efficiency for repetitive API calls or resource loading.

Stream prioritization and server push allowed more intelligent control over asset delivery, though push adoption has remained limited.

HTTP/2 still suffers from TCP-level HOL blocking. If one packet is lost, all multiplexed streams stall, hurting performance under lossy or mobile conditions.

HTTP/3 replaces TCP with QUIC, a UDP-based protocol that eliminates HOL blocking by multiplexing streams directly at the transport layer.

QUIC supports 0-RTT handshakes, reducing connection setup latency, which is critical for HTTPS connections and mobile responsiveness.

TLS 1.3 is built into QUIC, making all HTTP/3 communication encrypted by default and simplifying protocol layering.

Adoption of HTTP/3 is growing. Major platforms like Google, Facebook, and Cloudflare already use HTTP/3 at scale, and most modern browsers now support it.