Every modern application, from a ride-hailing service to an e-commerce platform, relies on data, and behind that data sits a database. Whether it's storing customer profiles, tracking inventory, or logging user actions, the database is more than just a storage engine. It's the core system that holds an application’s state together. When the database fails, everything else (APIs, front-end, business logic) comes tumbling down.

Therefore, choosing the right kind of database is critical, but it isn't a one-size-fits-all decision.

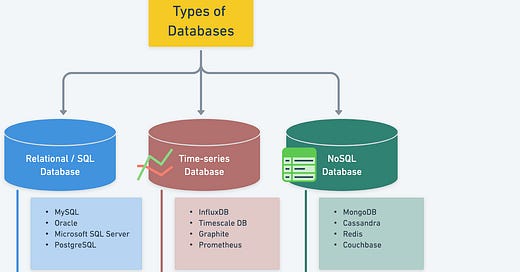

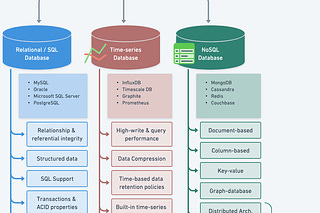

Relational databases, such as MySQL and PostgreSQL, have been the default for decades. They offer strong consistency, well-understood query languages, and battle-tested reliability. However, as systems scale and use cases diversify, traditional SQL starts to exhibit problems.

That’s where NoSQL enters the picture with a flexible schema design, horizontal scalability, and models tailored to specific access patterns. The promise is to scale fast and iterate freely. However, there are trade-offs in consistency, structure, and operations.

Then there’s a growing third category: NewSQL systems such as Google Spanner and CockroachDB. These attempt to bridge the gap by retaining SQL semantics and ACID guarantees, while scaling like NoSQL across regions and nodes. There are also specialized databases that push performance in specific directions. In-memory stores like Redis blur the line between cache and persistence. Search engines like Elasticsearch offer lightning-fast text search and analytics capabilities that relational databases were never built for.

The wrong database choice can throttle performance, slow down development, or break under scale. The right one can unlock speed, agility, and reliability.

In this article, we break down the core database paradigms, such as SQL and NoSQL, along with specialized database types and how developers can choose the appropriate database for their requirements.

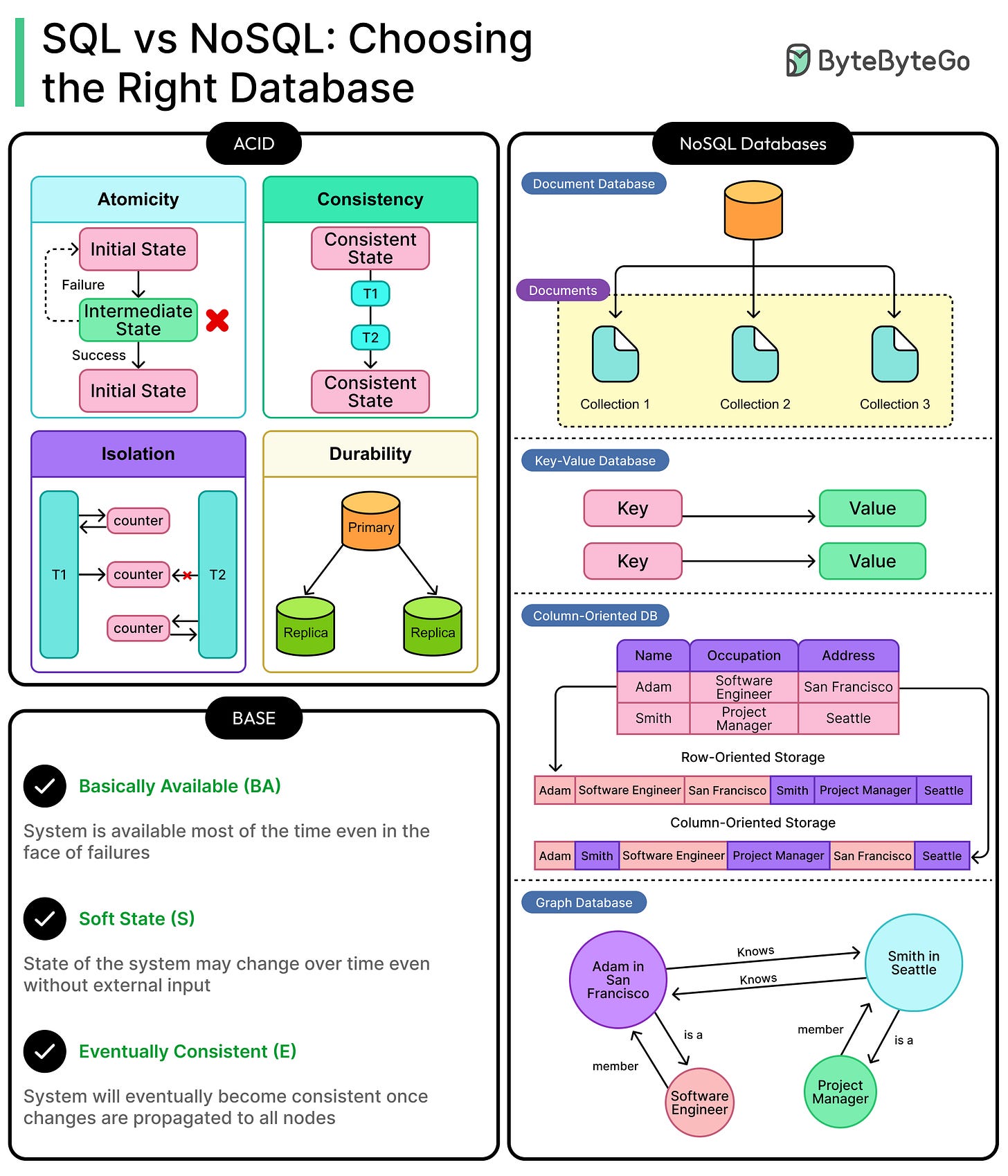

Core Models: ACID vs BASE

Every database promises to store and retrieve data, but how it handles correctness, concurrency, and failure defines its trustworthiness.

At the heart of this are two contrasting models: ACID and BASE. One prioritizes consistency and correctness while the other leans into scalability and resilience.

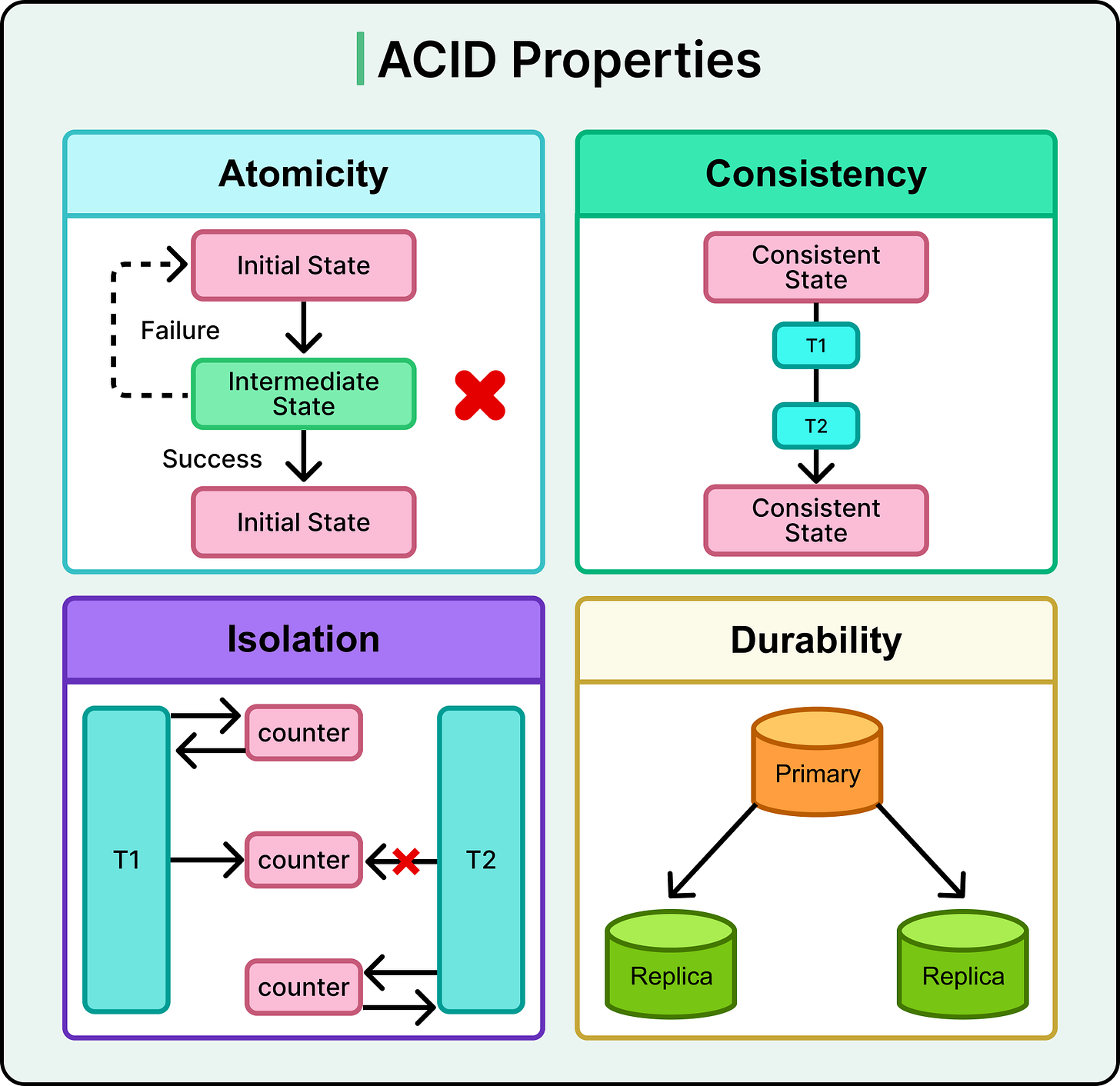

ACID

The ACID model governs how most traditional relational databases operate. The term stands for:

Atomicity: Transactions either complete in full or not at all. If a bank transfer debits one account but fails to credit another, the whole transaction rolls back.

Consistency: A transaction moves the database from one valid state to another, enforcing constraints and rules. For instance, a column expecting a positive integer won’t accept a string or a negative number, even under concurrency.

Isolation: Transactions don't interfere with each other. Even if two users try to book the last seat on a flight simultaneously, only one succeeds. Isolation levels (like Serializable or Read Committed) control how concurrent transactions interact.

Durability: Once a transaction commits, its changes persist even if the server crashes the next moment. The data is flushed to disk or replicated before acknowledgment.

ACID is non-negotiable in systems where correctness is the most important property. Think banking, e-commerce checkout flows, or healthcare records. These applications cannot afford to show stale or partial data, even under heavy load or failure. See the diagram below:

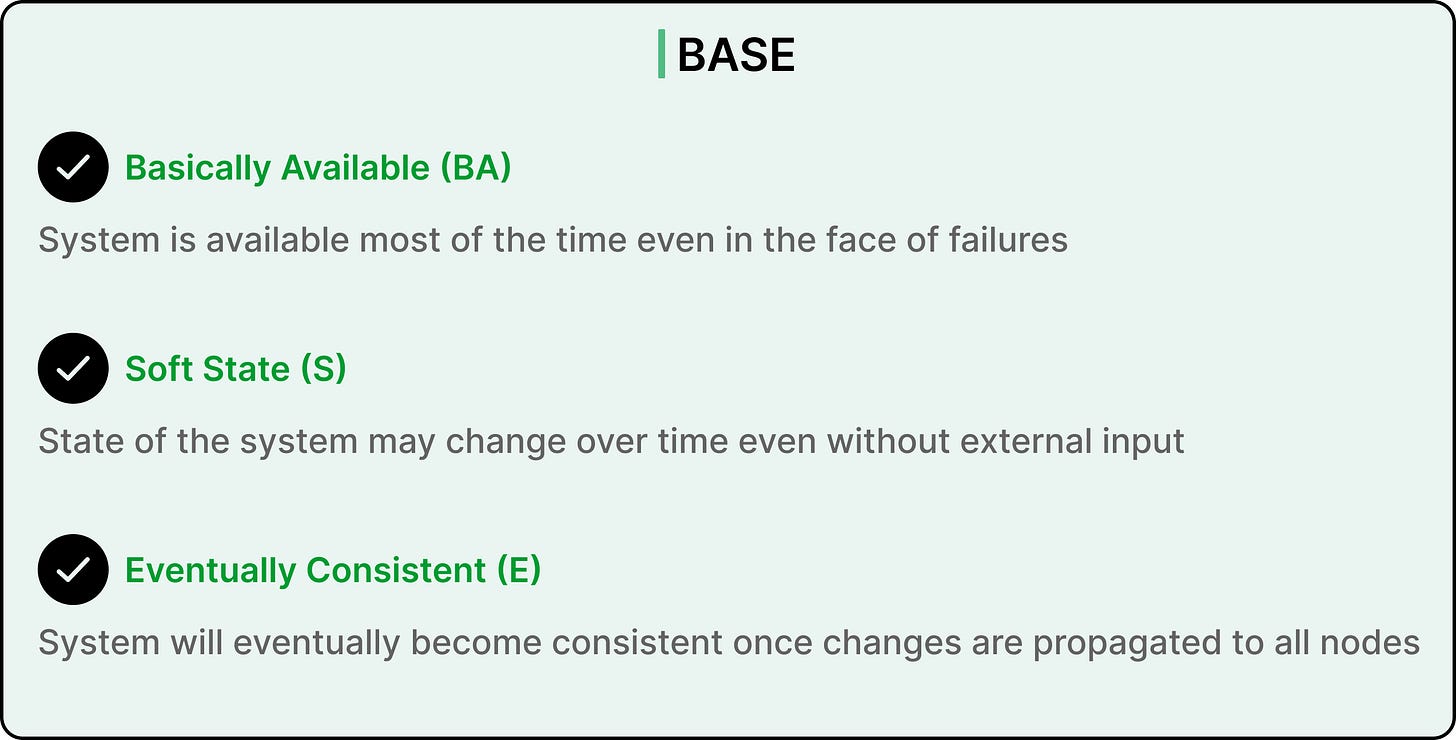

BASE: Designed for Distribution

On the other side is BASE, the model adopted by many NoSQL systems operating at internet scale. BASE stands for:

Basically Available: The system stays up and responsive, even if some parts are unreachable or inconsistent.

Soft state: The state of the system may change over time, even without new inputs, due to background processes like replication or repair.

Eventually consistent: Data replicas may diverge temporarily but converge over time. If a user posts a comment, it might appear immediately on one device and a few seconds later on another.

BASE relaxes the rigidity of ACID to accommodate high availability and partition tolerance. This makes sense in systems that prioritize uptime and scale, such as social media timelines, real-time analytics, and IoT ingestion pipelines. These systems can tolerate temporary inconsistency as long as they never go down.

The Trade-Offs

To understand trade-offs, let’s consider two real-world examples:

A banking transaction transferring $100 from Account A to Account B demands ACID. Atomicity ensures funds don’t vanish or duplicate. Consistency enforces business rules. Isolation prevents race conditions during concurrent transfers. Durability guarantees the transaction survives hardware failures.

A social media feed, by contrast, can’t afford to block rendering just because one replica is catching up. If a friend posts a photo, and it doesn’t immediately show up on every device, the world doesn’t end. Users expect low latency and high availability, even if it means reading slightly stale data. Here, BASE appears as the better choice.

However, there are things to consider in both cases. ACID simplifies correctness but doesn’t scale effortlessly across distributed regions. BASE scales wide but puts the burden of eventual correctness on application logic or user tolerance.

The challenge is not choosing a “better” model, but choosing the right model based on the guarantees the application must uphold and the failures it must handle.

SQL Databases: The Relational Foundation

Relational databases sit at the heart of most traditional software systems for good reason.

They organize data into structured tables (rows and columns) with explicitly defined schemas. Each table represents a distinct entity: users, orders, products, and transactions. Columns define attributes, while relationships between tables are enforced using foreign keys. The result is a predictable, tabular structure where data fits neatly into a grid.

At the center of relational databases is SQL (Structured Query Language). SQL offers a declarative way to interact with data: insert, update, fetch, and read. Developers write queries that describe what they want, not how to compute it. The database engine takes care of optimization, planning, and execution.

Why RDBMS Still Matters?

Despite the rise of NoSQL, relational databases remain the default choice for a large number of applications. They bring decades of maturity, tooling, and operational knowledge.

Their strengths include:

Transactional Safety: Full ACID compliance ensures data integrity under concurrent access and failure scenarios. This matters deeply for applications like banking, inventory management, or accounting.

Schema: The rigid schema model enforces data shape at the database layer, not just in application code. This avoids corruption and makes migrations explicit.

JOIN Capabilities: Relational databases excel at joining normalized data across tables, something that NoSQL systems typically avoid or push to the application layer.

Tooling Ecosystem: From query planners and performance profilers to replication setups and failover strategies, the ecosystem around RDBMSs is rich and well-understood.

MySQL vs. PostgreSQL

Among open-source RDBMSs, MySQL and PostgreSQL dominate.

MySQL is valued for its simplicity and speed, especially in read-heavy workloads. It powers massive platforms like WordPress and Facebook’s early infrastructure. Its replication capabilities and LAMP-stack friendliness made it ubiquitous in web applications.

PostgreSQL, on the other hand, offers rich data types, full-text search, stored procedures, user-defined functions, and powerful extensions like PostGIS (for geospatial data) and TimescaleDB (for time-series). It embraces SQL standards more rigorously and supports advanced features like transactional DDL and window functions.

Technical Considerations

Working with relational databases demands knowledge of certain structural and performance design patterns:

Indexing: Proper indexing on primary keys, foreign keys, and frequently queried fields can speed up queries dramatically. However, over-indexing can slow down writes and increase storage overhead.

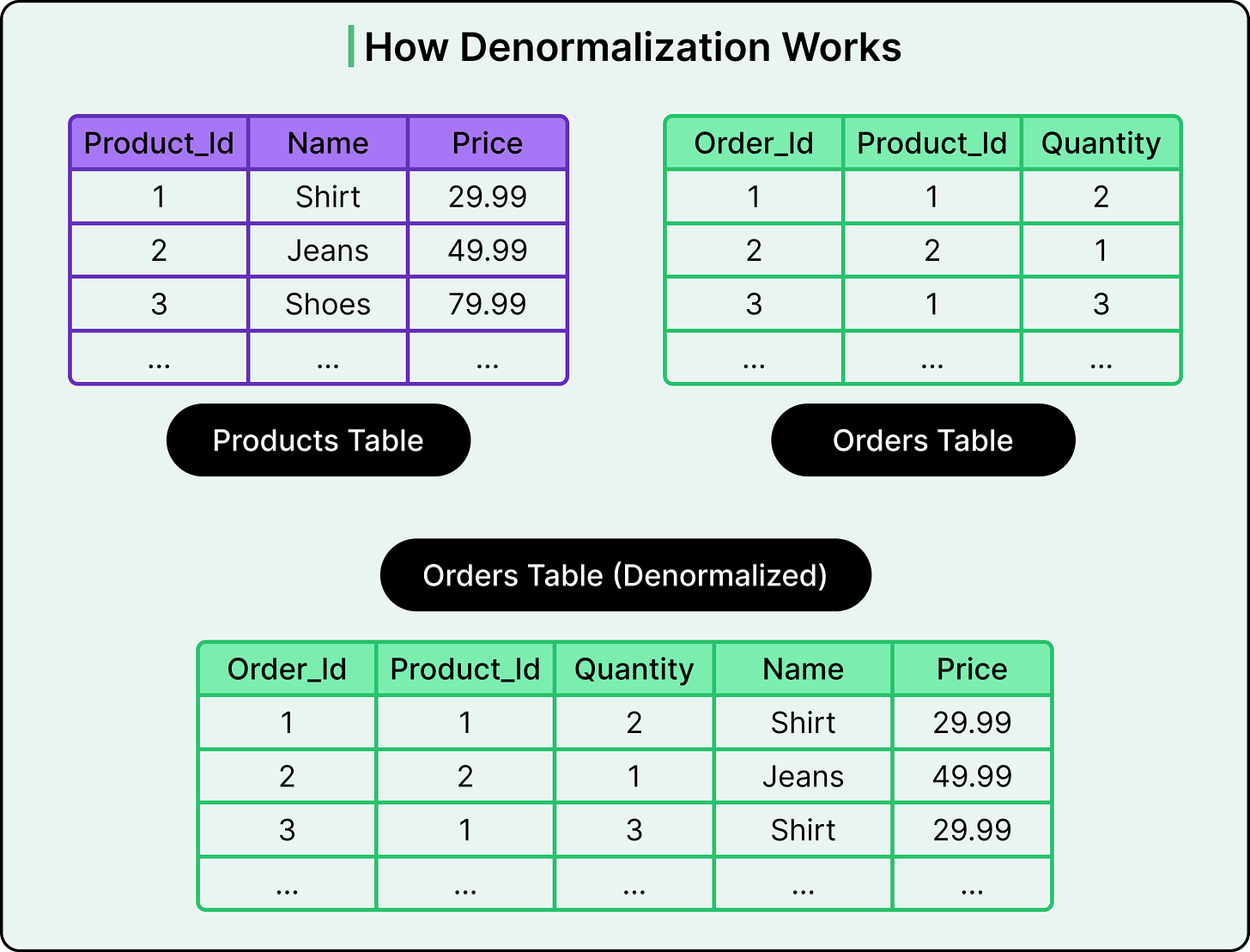

Normalization Versus Denormalization: Normalization reduces redundancy by splitting data into multiple related tables. It keeps the data clean but increases JOIN complexity. Denormalization duplicates some data to simplify queries or improve performance. It's a trade-off: normalized schemas are elegant but sometimes slower; denormalized schemas are faster but harder to maintain.

JOIN Operations: JOINs are a double-edged sword. They enable powerful queries across multiple tables but can become performance bottlenecks if not backed by proper indexes or if executed on large datasets.

NoSQL Databases

Relational databases offer structure and safety, but they weren’t designed for the scale, speed, and data diversity that modern applications demand.

As systems grew to support billions of users, distributed architectures, and real-time interactivity, cracks began to show. Schema migrations became painful. JOINs slowed things down. Scaling vertically hit a wall. That’s where NoSQL databases entered the picture.

NoSQL is a category of data stores designed to address the shortcomings of relational models in large-scale, distributed environments. These databases throw off rigid schemas in favor of flexibility, prioritize high availability, and scale horizontally from the ground up. What they sacrifice in consistency or query richness, they gain in scalability, speed, and operational resilience.

There are multiple types of NoSQL databases that can be considered:

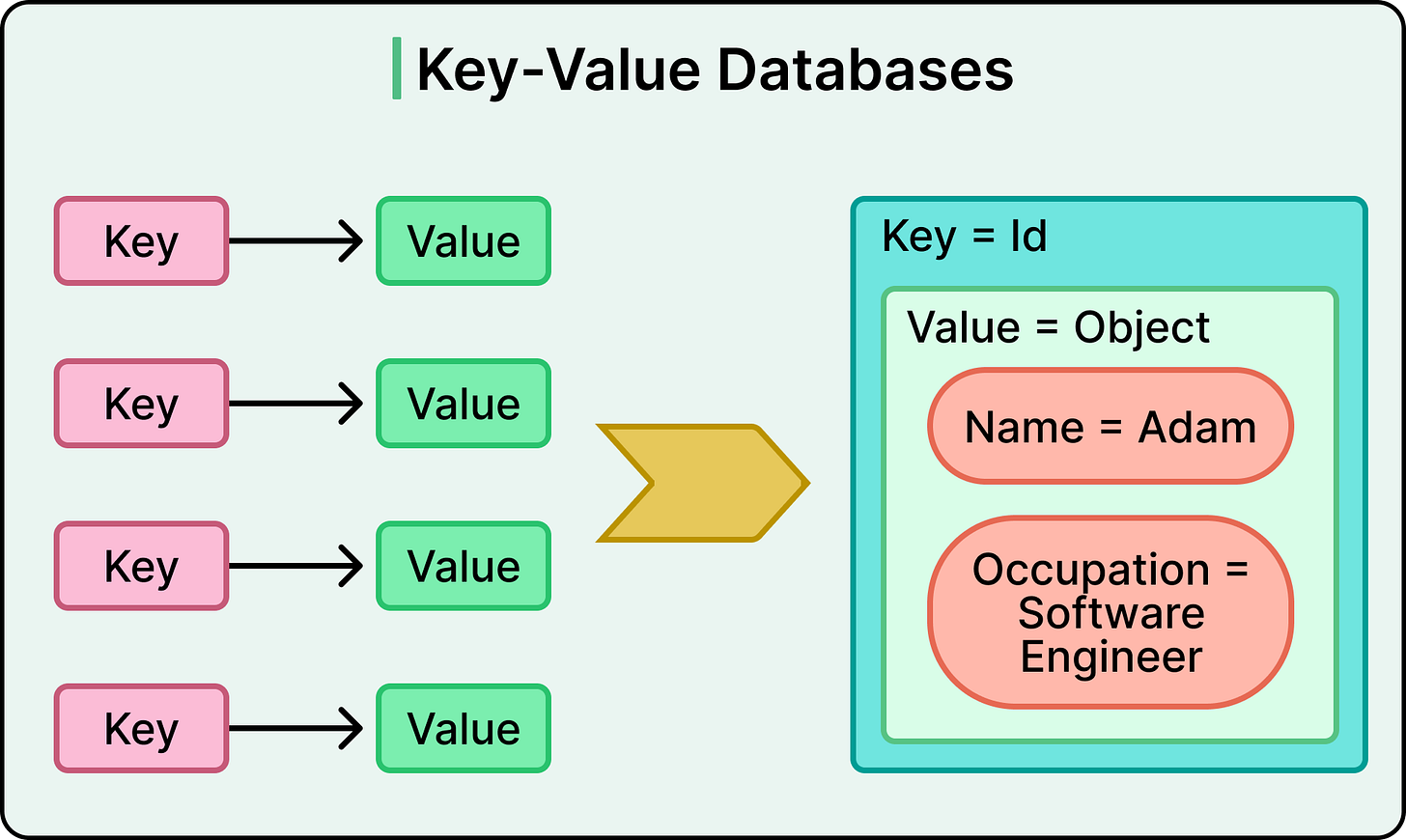

Key-Value Stores

Key-value databases follow the most straightforward model: store a value, retrieve it later using a key. There's no query language, no relational structure, and minimal overhead.

Redis and DynamoDB are among the most popular in this category. Redis keeps everything in memory for ultra-fast access, making it ideal for caching, leaderboards, session tokens, and rate-limiting. DynamoDB persists data and offers global distribution, with strong integration into AWS workflows.

These databases scale horizontally with relative ease. Partitioning (or sharding) keys across multiple nodes distributes the load automatically.

The trade-off is no built-in support for secondary indexes or complex queries. For example, if there is a requirement to filter values or sort by a field inside a JSON blob, the logic typically lives in application code or adjacent services.

Key-value stores work well when access patterns are predictable and performance is critical.

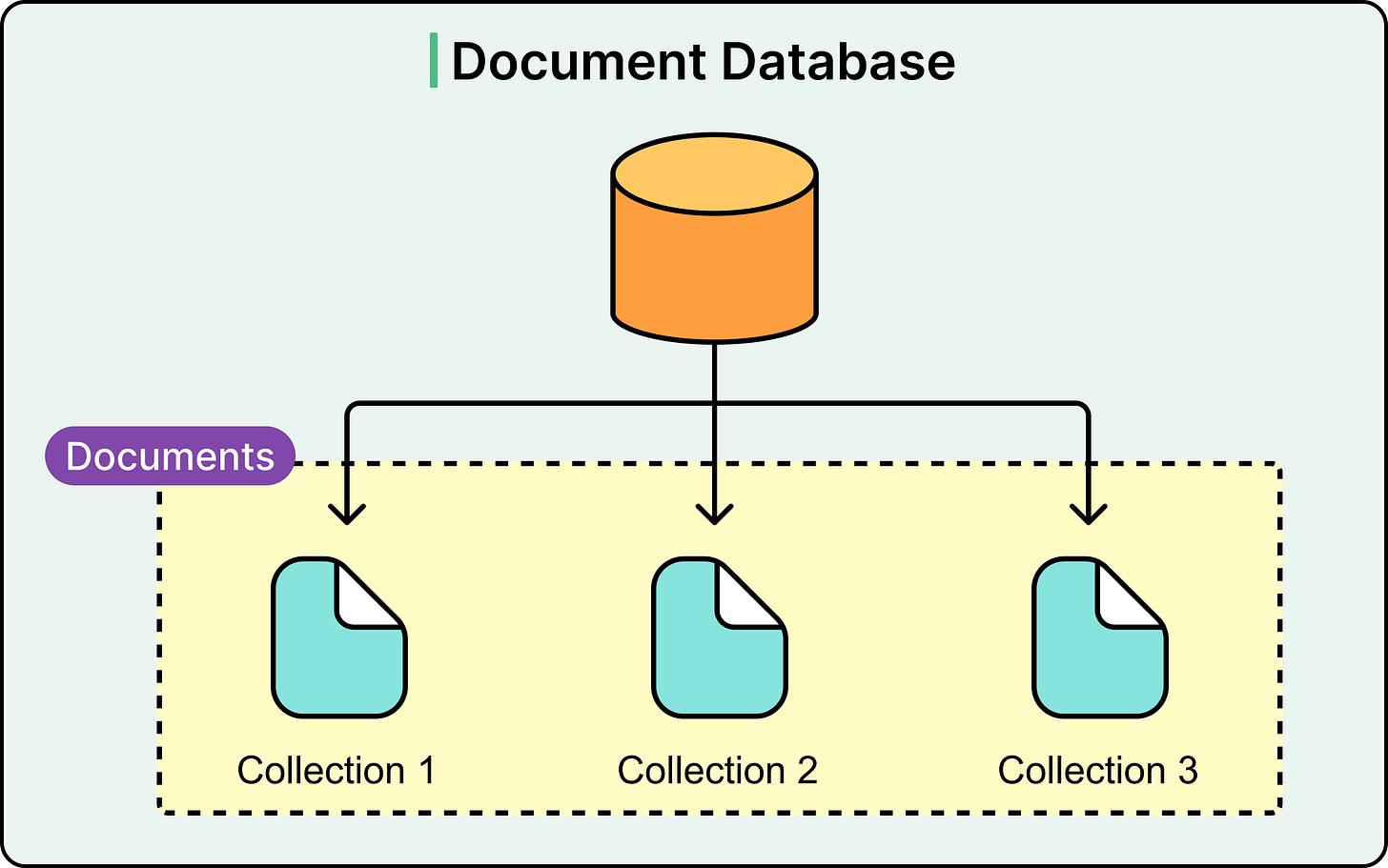

Document Stores

Document databases take a more nuanced approach. Instead of rows and columns, they store entire documents typically in JSON, BSON, or similar formats.

Each document is self-contained and may have its own schema.

MongoDB and Couchbase lead this category. They allow deeply nested, hierarchical data and support rich querying on any document field. A user document might contain embedded addresses, orders, and preferences, all retrievable with a single query.

These databases thrive in systems where data shapes evolve: content management systems, product catalogs, mobile backends, or any domain where flexibility outweighs rigid enforcement.

They scale horizontally through automatic sharding and replication. Consistency can be tuned: MongoDB, for example, lets clients specify read/write concern levels, trading off between speed and accuracy.

JOINs across collections are discouraged or absent. Instead, data is denormalized and duplicated across documents for performance. This makes writing more complex, but it reads blazingly fast.

Document stores shine when working with semi-structured data, evolving schemas, or domains where read performance dominates.

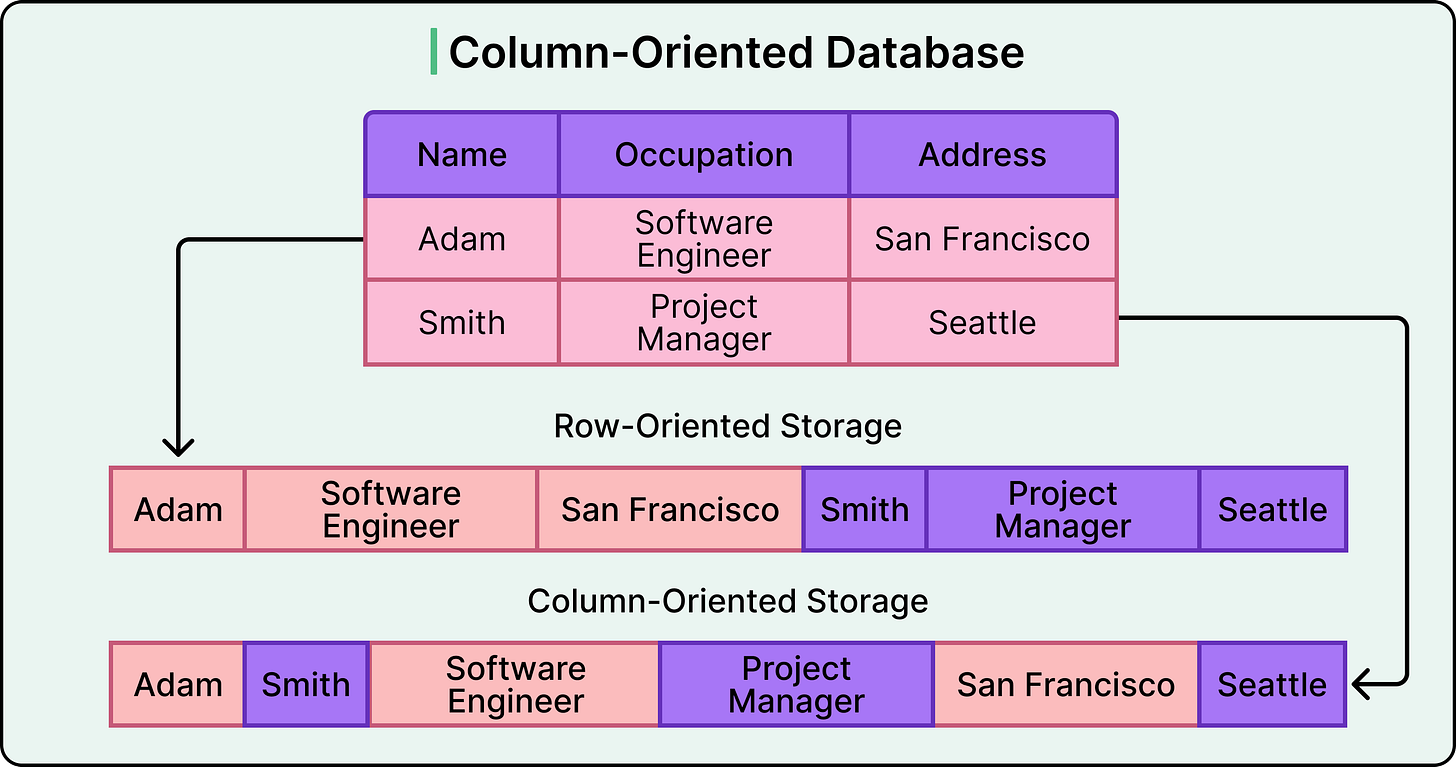

Column-Family Stores

Column-family databases store data in a fundamentally different way. Instead of rows, they group related columns into families, optimized for wide and sparse datasets. Think of them as multi-dimensional key-value stores.

Some key features are as follows:

They are built for write-heavy workloads with low-latency read guarantees, making them popular for telemetry, logging, time-series data, and real-time analytics.

These databases scale linearly. Add nodes, and throughput increases. There’s no single point of failure, and replication strategies are highly configurable.

Queries are based on a primary key pattern. Design the schema around access paths. There’s no ad hoc querying like in SQL. If the pattern shifts, the schema must shift too.

Consistency is tunable. For example, in certain databases, it's possible to choose between strong consistency (read from quorum) and eventual consistency (read from any node).

See the diagram below to understand the concept of a column-oriented database.

Graph Databases

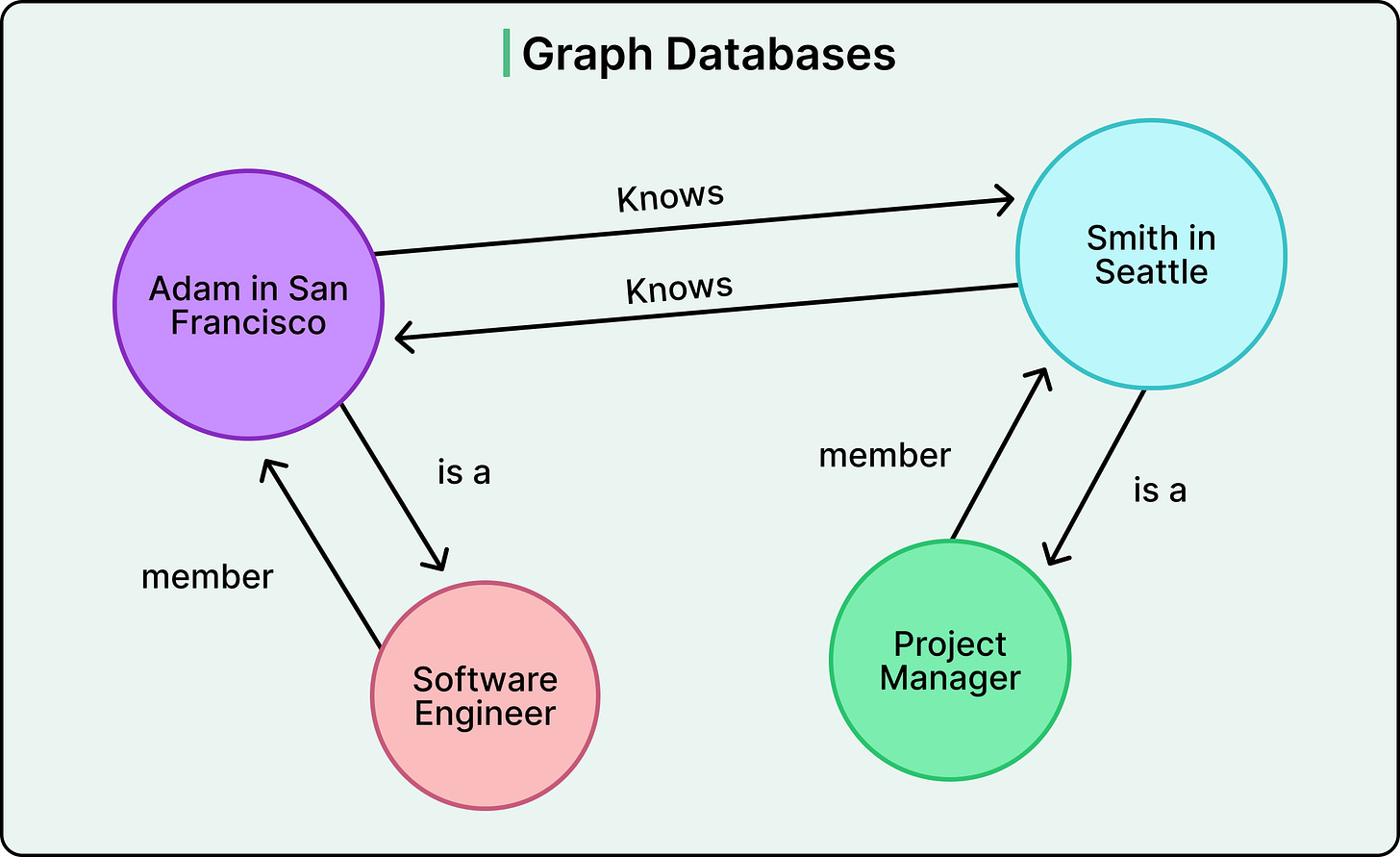

Some problems aren’t about records, but about relationships.

Who follows whom? Which product leads to which recommendations? How are fraud networks connected? These are the typical domains of graph databases.

Some key features of graph databases are as follows:

Graph databases model data as nodes (entities) and edges (relationships), with both capable of holding properties. This structure makes them ideal for traversing complex networks.

Neo4j and Amazon Neptune are widely used graph engines. Neo4j uses the Cypher query language to express path-based queries cleanly. For example, finding “all users who liked a post liked by someone I follow” becomes a simple graph traversal.

These databases prioritize relationship depth and query flexibility over raw throughput. Traditional RDBMS JOINs can simulate some of this, but they degrade quickly with recursive depth.

Scaling graph databases is hard. Most operate best on large, vertically scaled instances. Distributed graphs exist, but they introduce non-trivial partitioning challenges.

See the diagram below for reference:

NewSQL

Relational databases offer strong guarantees but struggle to scale horizontally.

NoSQL systems scale beautifully but compromise on consistency and query richness. Somewhere in between lies a third path: NewSQL.

NewSQL databases aim to retain the relational model and full ACID guarantees while delivering the horizontal scalability, fault tolerance, and availability typically associated with NoSQL systems. They do this by redesigning the storage engine, query planner, and consensus layer from the ground up to work in distributed environments.

The result is a system that looks and feels like traditional SQL, but under the hood, it’s built to span data centers, regions, and even continents.

NewSQL databases shine in the following areas:

Global transactional workloads: Applications that need to write across regions and maintain ACID guarantees.

High availability with consistency: Systems that cannot afford to lose transactions or tolerate inconsistent reads.

PostgreSQL compatibility: This allows many existing tools and ORMs to work out of the box.

Operational simplicity at scale: Compared to managing manual sharding in legacy RDBMS clusters.

The issue with NewSQL is as follows:

Latency overhead: Distributed consensus isn't free. Write paths, especially across regions, are slower than local RDBMS writes.

Operational maturity: While the systems abstract away a lot, debugging performance in distributed SQL systems can get complex quickly.

Cloud dependency: Managed versions of NewSQL databases come at a premium cost.

Learning curve: Understanding how data is partitioned, replicated, and queried in a distributed SQL system often requires a shift in mental models.

Let’s look at one popular NewSQL database in more detail.

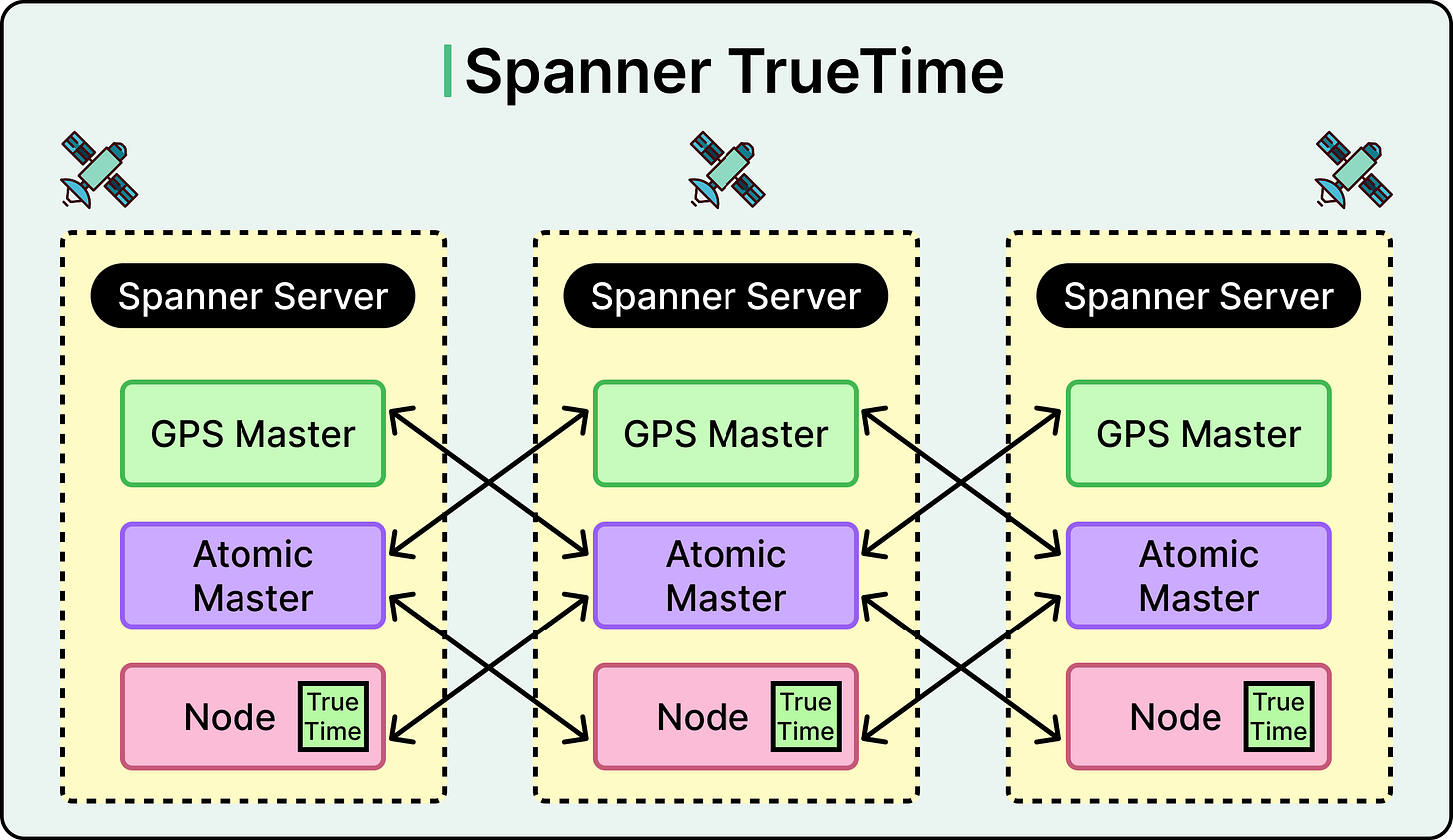

Google Spanner

Google Spanner is one of the first databases to offer global consistency, high availability, and horizontal scalability, all with SQL.

Spanner’s secret sauce is TrueTime, a globally synchronized clock API that uses atomic clocks and GPS receivers to bound uncertainty in distributed transactions. This allows Spanner to coordinate writes across the globe with tight consistency guarantees. See the diagram below for reference:

It also relies on Paxos-based replication to maintain consensus and tolerate node or region failures without losing availability or correctness.

Spanner supports ANSI SQL and operates like a relational database, but one that scales across continents. It’s used inside Google for services like AdWords and external-facing systems like Firebase and Cloud Spanner.

This level of consistency isn’t cheap. Writes incur coordination delays, and cross-region latency can’t be ignored. However, for systems like multi-region financial ledgers, customer data platforms, or critical SaaS backends, it’s often worth it.

Specialized Database Categories

Not all databases are built to store general-purpose application data.

Some are optimized for speed, temporal trends, or textual search. These specialized databases don’t always fit into the SQL vs. NoSQL debate, but they solve critical problems in modern systems.

Often, they don’t replace a primary database but augment it, powering specific workloads that would otherwise bottleneck or overload a traditional system.

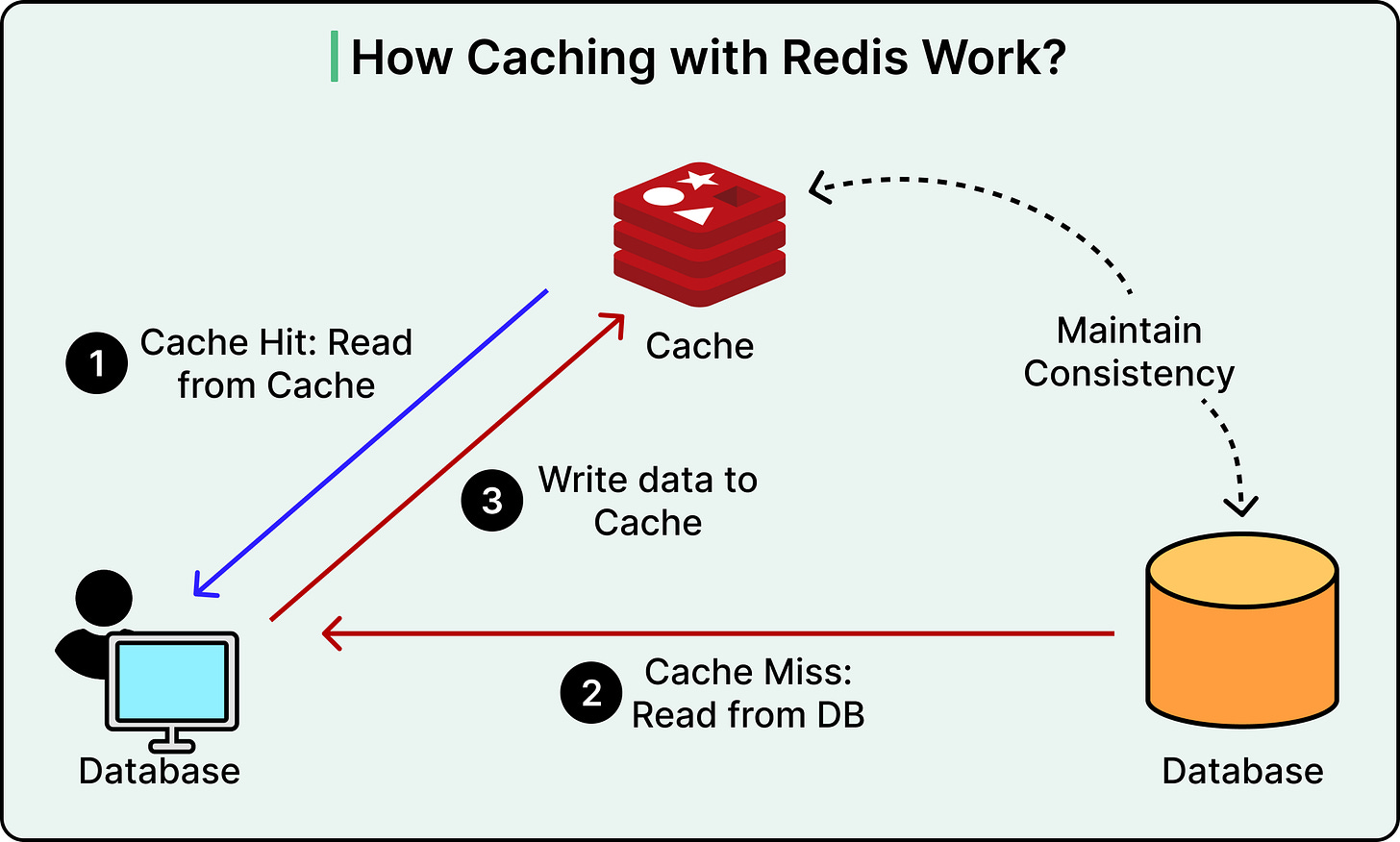

In-Memory Databases

Sometimes, speed matters more than durability.

That’s where in-memory databases come in. These systems keep data in RAM instead of disk, enabling sub-millisecond latency for reads and writes. They're perfect for use cases like:

Caching frequently accessed data

Session stores for web applications

Real-time leaderboarr counters

Pub-sub messaging and distributed locks

The two most widely used in-memory databases are Redis and Memcached.

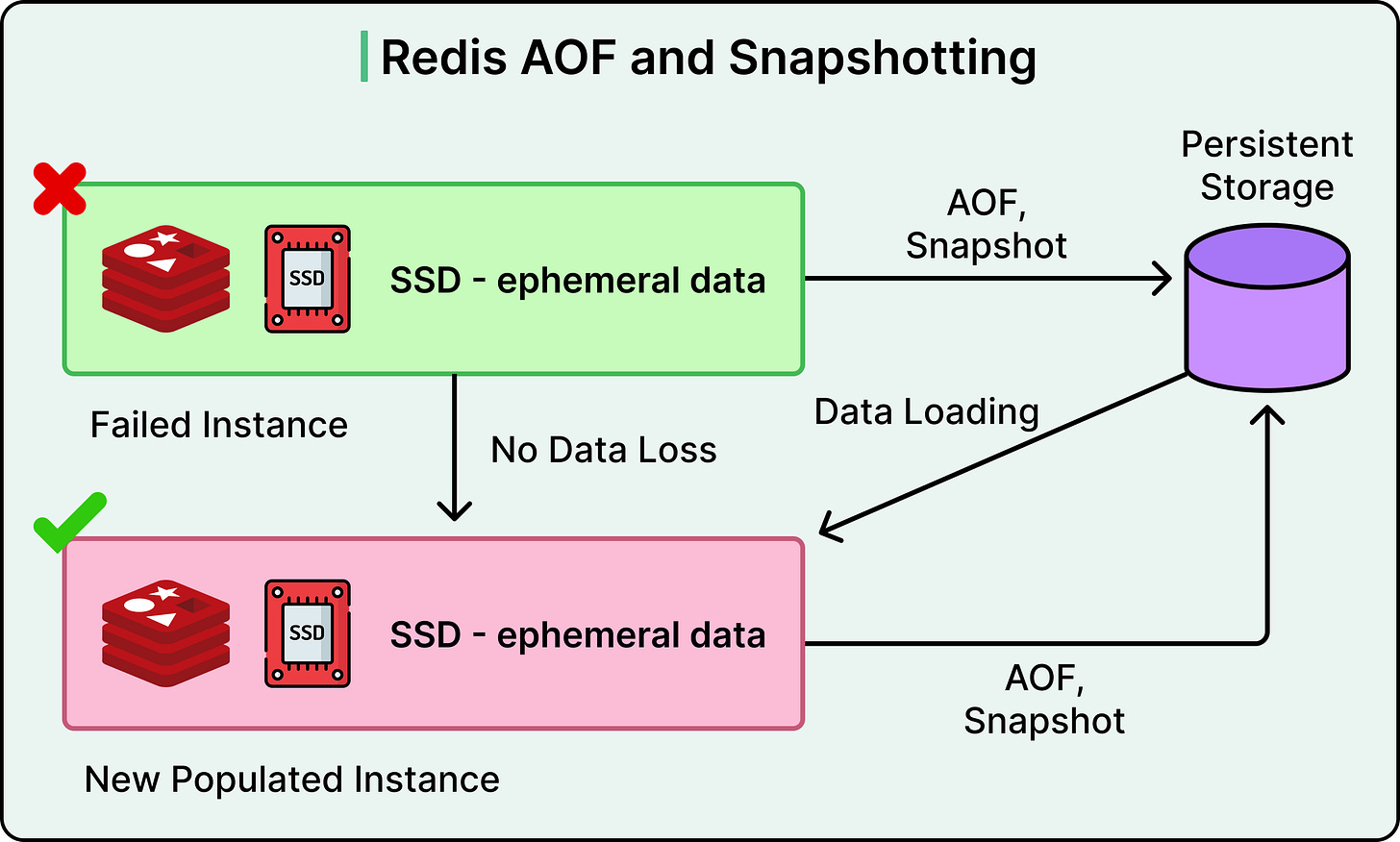

Redis is more than a simple cache. It supports complex data structures—lists, sets, hashes, sorted sets, and operations like atomic increments, expirations, and Lua scripting. It also supports persistence (RDB and AOF modes), replication, clustering, and pub-sub messaging, making it suitable for more than just transient data.

Memcached, in contrast, is simpler and faster for pure key-value caching. It has no persistence or advanced data types, but its memory management is efficient for small, volatile caches.

In-memory databases come with trade-offs:

Volatility: Unless configured to persist data (as with Redis), all data is lost on crash or restart.

Memory pressure: RAM is expensive. Careless use of large objects or unbounded key growth can result in eviction or node failure.

Scaling: Horizontal scaling is possible but comes with operational overhead, especially if data consistency or durability is a concern.

Used wisely, in-memory databases act as performance amplifiers. They can shield primary databases from repetitive queries and slash overall response times.

Time-Series Databases

When the data model revolves around timestamps, general-purpose databases start to have problems. Monitoring systems, financial tickers, IoT devices, and user telemetry produce massive streams of time-ordered data. That’s the realm of time-series databases (TSDBs).

Key TSDB features include:

Automatic downsampling to control storage growth over time.

Efficient range queries optimized for time-based filters and aggregations.

Retention and eviction policies to automatically discard old data.

As an example, a database like InfluxDB excels in pure telemetry pipelines where performance is everything. On the other hand, TimescaleDB works better when time-series data coexists with relational context.

Search Databases

Traditional databases aren’t built for text search. Ask them to match against unstructured strings, fuzzy phrases, or analyze millions of logs, and they’ll face challenges. That’s where search databases like Elasticsearch and Apache Solr shine.

Both are built on inverted indexes. This allows extremely fast retrieval of relevant documents based on tokens, filters, and scoring algorithms.

Elasticsearch is the more popular of the two, widely used in log analytics, site search, product catalogs, and observability platforms like the ELK stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, and Kibana). It offers tokenization, stemming, relevance scoring, and aggregations out of the box.

Solr, built on Apache Lucene like Elasticsearch, offers similar capabilities but is preferred in some enterprise contexts for its XML-based configurations and mature plugin architecture.

Common use cases of search databases include:

Full-text search with ranking.

Faceted navigation for e-commerce or dashboards.

Log aggregation and analytics (for example, Kibana on top of Elasticsearch).

Alerting and anomaly detection on textual or semi-structured data.

These aren’t general-purpose databases. They don’t enforce ACID guarantees, and they aren't optimized for transactional workloads. But as secondary engines layered on top of SQL or NoSQL systems, they open up powerful query capabilities that traditional databases find difficult to apply.

When to Use Which Database?

No single database fits every workload. The right choice depends on what the system needs to guarantee, how the data evolves, and where the performance bottlenecks lie.

Here are some points that can help developers make the right choice:

Use SQL when correctness is non-negotiable. Systems that rely on transactional integrity, strict schemas, and relational querying, like banking platforms, benefit from the structure and reliability of relational databases.

Use NoSQL when the application needs to move fast and scale wide. In systems where schemas change frequently, data volume grows unpredictably, or uptime is more important than immediate consistency, such as social feeds, mobile backends, or analytics pipelines, NoSQL databases offer the flexibility and resilience needed.

Use NewSQL when global scale and ACID guarantees must coexist. Multi-tenant SaaS platforms, financial systems spanning regions, and enterprise platforms with strong relational logic but distributed infrastructure all benefit from NewSQL’s blend of transactional safety and horizontal scalability.

Use in-memory databases when speed matters more than persistence. Leaderboards, live counters, rate-limiters, or anything that demands microsecond latency fits well with Redis or Memcached.

Use time-series databases when tracking data over time is the core workload. Metrics, sensor readings, uptime logs, and telemetry streams are best handled by engines designed to slice, downsample, and aggregate time-indexed data.

Use search databases when the system requires full-text search, filtering, or fuzzy matching. Product discovery in e-commerce, log analysis in observability stacks, and document retrieval all depend on the kind of indexing and scoring that Elasticsearch or Solr provides.

Summary

In this article, we have looked at various database types and their pros and cons.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Relational databases follow the ACID model to ensure strict data integrity, making them ideal for transactional systems where correctness matters more than scale.

NoSQL databases adopt the BASE model to prioritize availability and partition tolerance, often at the cost of immediate consistency.

SQL databases like MySQL and PostgreSQL provide mature tooling, robust transaction support, and rich querying through JOINs and aggregations.

MySQL offers simplicity and speed for read-heavy workloads, while PostgreSQL excels in extensibility and standards compliance.

NoSQL databases come in four main types: key-value stores (for example, Redis, DynamoDB), document stores (for example, MongoDB), column-family stores, and graph databases (for example, Neo4j), each optimized for different data models and access patterns.

Key-value stores deliver ultra-fast lookups for simple data access but lack query flexibility.

Document stores support semi-structured data with flexible schemas and are suited for rapidly evolving applications like content platforms.

Column-family databases handle high write throughput and time-series-like access patterns, trading off ad-hoc query support.

Graph databases model relationships natively and work well for complex network queries, though they can be harder to scale.

NewSQL databases like Google Spanner try to offer SQL semantics and ACID guarantees with distributed scalability, making them suitable for global, transactional workloads.

In-memory databases like Redis and Memcached deliver low-latency performance for caching, pub-sub, and real-time counters, but may lose data on a crash unless persistence is configured.

Time-series databases are built for high-ingestion, time-indexed data and support features like downsampling and retention policies.

Search databases like Elasticsearch and Solr enable full-text search, relevance scoring, and log analytics through inverted indexes, complementing primary databases in search-heavy workloads.

What was meant by "The trade-off is no built-in support for secondary indexes or complex queries" in regards to Redis and DynamoDB? DynamoDB supports Global Secondary Indexes (GSI) and Local Secondary Indexes (LSI).