Every modern application relies on data, and users expect that data to be fast, current, and always accessible. However, databases are not magic. They can fail or slow down under load. They can also encounter physical and geographic limits, which is where replication becomes necessary.

Database Replication means keeping copies of the same data across multiple machines. These machines can sit in the same data center or be spread across the globe. The goal is straightforward:

Increase fault tolerance.

Scale reads.

Reduce latency by bringing data closer to where it's needed.

Replication sits at the heart of any system that aims to survive failures without losing data or disappointing users. Whether it's a social feed updating in milliseconds, an e-commerce site handling flash sales, or a financial system processing global transactions, replication ensures the system continues to operate, even when parts of it break.

However, replication also introduces complexity. It forces difficult decisions around consistency, availability, and performance. The database might be up, but a lagging replica can still serve stale data. A network partition might make two leader nodes think they’re in charge, leading to split-brain writes. Designing around these issues is non-trivial.

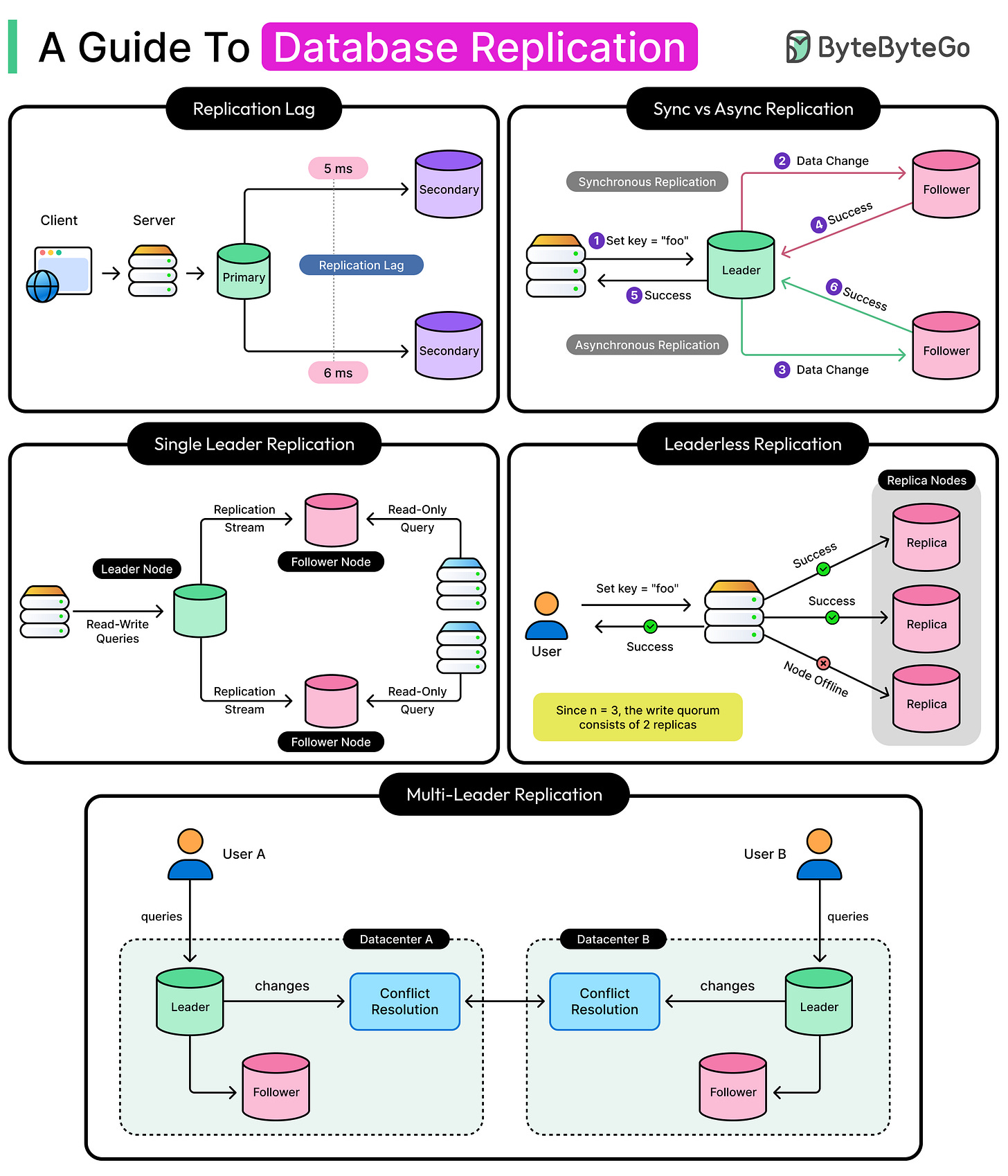

In this article, we walk through the concept of replication lag and major replication strategies used in distributed databases today. We will cover single-leader, multi-leader, and leaderless replication models, breaking down how each works, what problems they solve, and where they fall apart.

Why Replicate Data?

Replication is foundational to how modern systems stay online, stay fast, and stay correct when things go wrong.

At its core, replication provides redundancy. If one machine goes offline due to hardware failure, software bugs, or network issues, another can take its place. That’s the basis of high availability. Without replication, a database outage becomes a system outage.

It also enables geographic distribution. In a world where users can connect from New York, Singapore, and Sydney, having all data in a single region creates unnecessary latency. Replication allows placing data closer to users, cutting round-trip times and making applications feel faster.

Read scalability is another driver. As traffic grows, a single database node can become a bottleneck, especially for read-heavy workloads. With replication, secondary replicas can serve read traffic without burdening the primary node. This pattern shows up in social networks, analytics dashboards, and public APIs where reads vastly outnumber writes.

Disaster recovery is another related but distinct use case. Replication ensures there’s always a recent copy of the data available, even if an entire region or data center fails. Systems with aggressive recovery targets (low RTO/RPO) rely heavily on real-time replication across fault domains.

Certain workload types make replication indispensable:

Multi-region applications require replicas in each geography to ensure low-latency access and local failover.

High-throughput services like search, recommendation engines, and telemetry pipelines use replicas to absorb load spikes without slowing down writes.

While replication makes these systems viable, it also introduces new challenges such as data consistency, replication lag, failover complexity, and write coordination across nodes. These challenges shape the design of replication strategies.

Replication Lag and Consistency

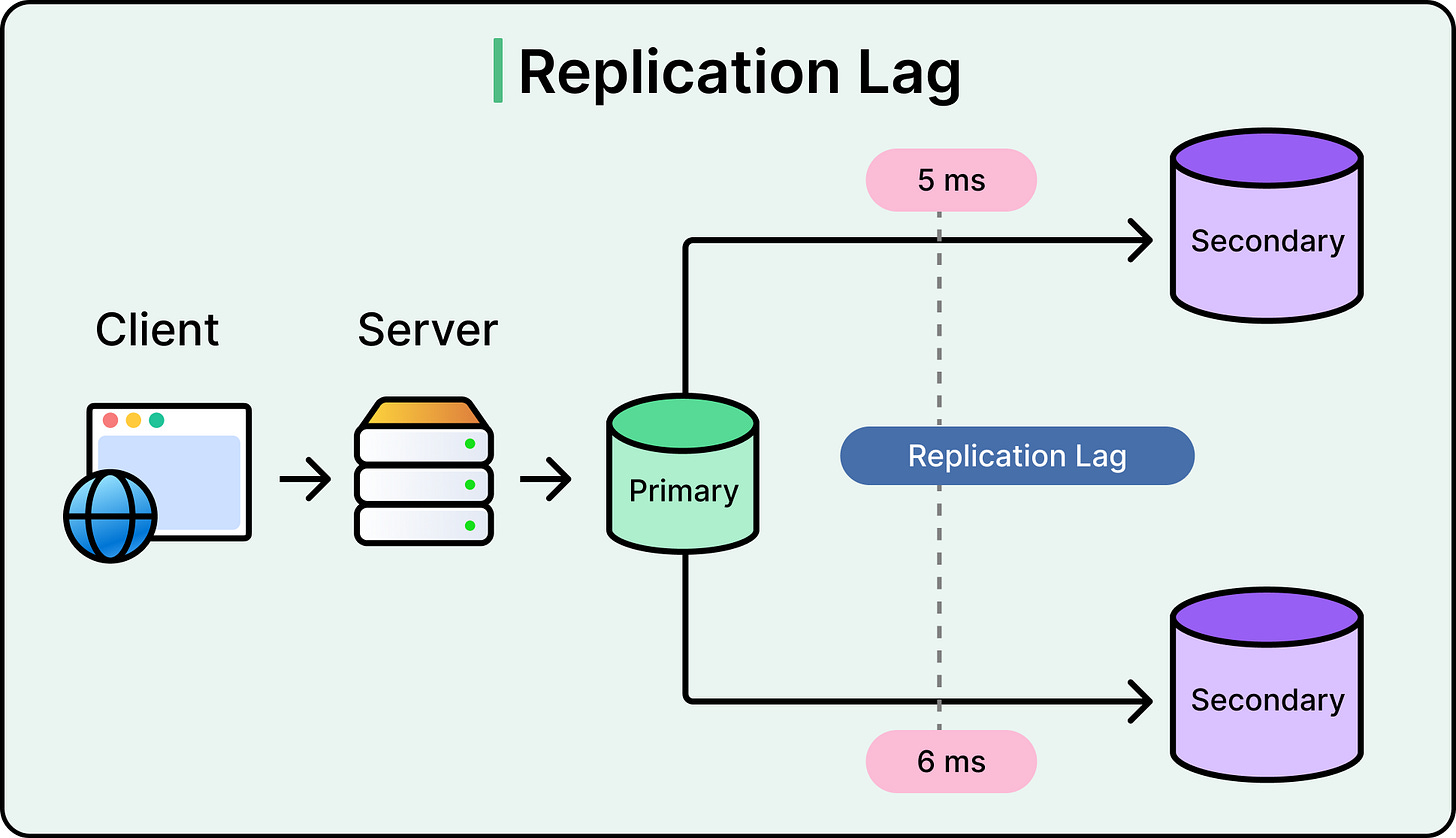

As mentioned, replication solves availability problems, but it creates consistency challenges. The most visible of these is replication lag: the delay between a write landing on the primary node and that change showing up on its replicas. In some systems, that delay is measured in milliseconds. In others, it can stretch into seconds or even minutes under load or failure.

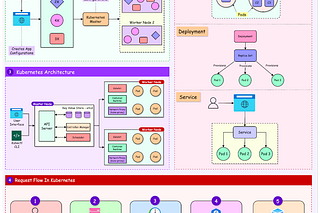

See the diagram below:

Replication lag matters because it breaks the assumption that all users see the same data at the same time.

For example, a user might update their profile photo, and immediately after, refresh the page, only to see the old one still showing. That’s not a bug in the UI. It’s a read from a replica that hasn’t caught up yet. These are stale reads, and they are a natural side effect of asynchronous replication.

This brings us into the territory of consistency models. In distributed systems, consistency exists on a spectrum:

At one end is strong consistency, in which every read reflects the latest write, no matter where it hits.

At the other end is eventual consistency, where replicas will converge, but not instantly. Most real-world systems fall somewhere in between.

The trade-off often comes down to latency versus consistency. To serve reads with low latency, replicas need to be close to users. But if those replicas aren't perfectly in sync with the primary, users may see old data. To get strong consistency, the system may require coordination with the primary or with a quorum of replicas, which increases response time.

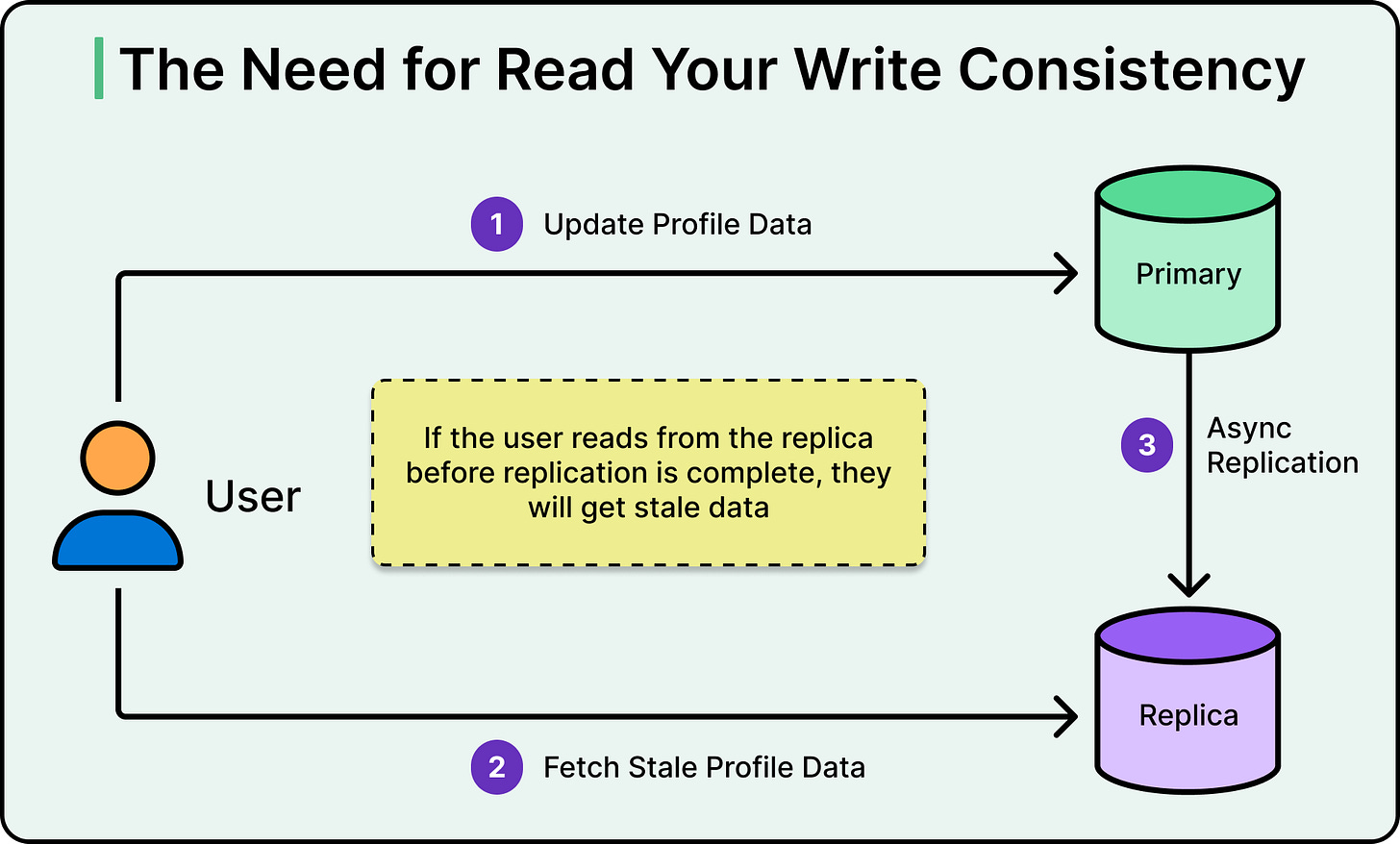

The situation becomes more complex when factoring in isolation levels and read guarantees. Many developers assume that once a write returns as successful, any subsequent read will reflect it. This is the read-your-writes guarantee. However, in a replicated setup, especially one using asynchronous replication, that isn’t automatic. Reading from a lagging replica can violate this expectation, leading to confusing user experiences and subtle bugs.

See the diagram below that shows the need for read-your-writes consistency:

Replication improves system resilience, but only when the consistency model is well understood and explicitly designed for. Otherwise, the replication lag can create issues by tempting engineers into assuming that things are up to date when they’re not, which often only shows up during real outages or edge-case failures.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Replication

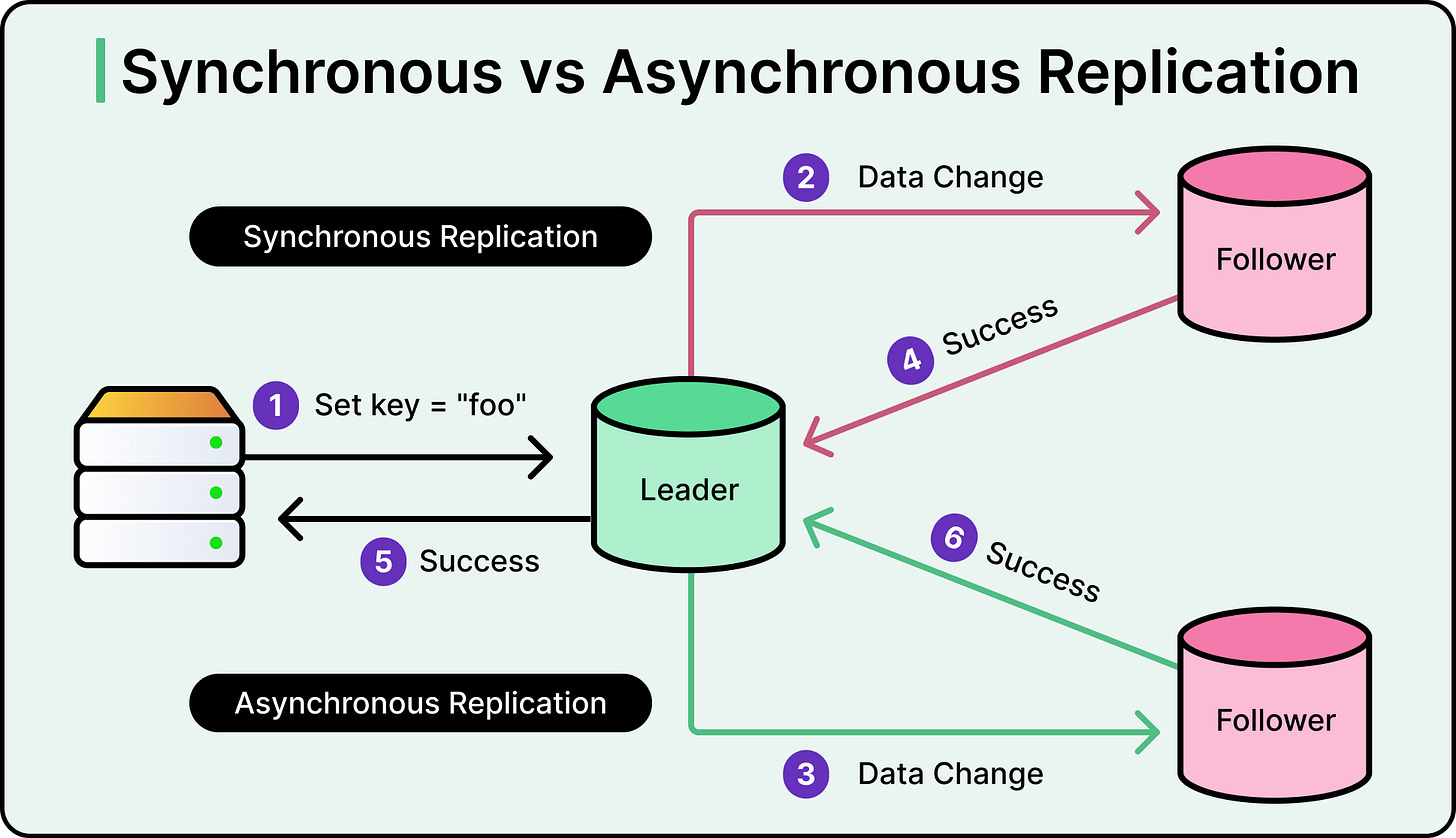

One important factor to consider in database replication is when the replicas are updated. The timing defines everything from how consistent the system feels to how it behaves under failure.

There are two approaches: synchronous and asynchronous. The diagram below shows both of them on a high level:

Synchronous Replication

In synchronous replication, a write is not considered successful until all required replicas have acknowledged it. The primary node coordinates with its replicas, waits for confirmation, and only then responds to the client. This guarantees that once a write is acknowledged, it exists in multiple places. If the primary crashes immediately after, at least one replica already has the write, which improves durability and consistency.

However, this safety comes with a cost.

Synchronous replication adds latency to every write. If one replica is slow, the whole system waits. If a replica goes down, the write path might block or fail until a quorum is reached or a reconfiguration happens.

Asynchronous Replication

In asynchronous replication, the primary node commits the write locally and returns success immediately. It then pushes the change to replicas in the background. This approach keeps latency low and isolates the primary from replica slowness.

However, the trade-off is consistency. If the primary crashes before replicas have caught up, those recent writes may be lost.

Trade-Offs

The distinction between synchronous and asynchronous replication matters in real-world systems. In financial platforms or inventory systems, losing even one acknowledged write is unacceptable. In those cases, teams can choose synchronous replication or introduce additional layers like write-ahead logs, external commit logs, or distributed consensus protocols to protect against data loss.

On the other hand, for systems like social media timelines or analytics dashboards, a few seconds of delay may be acceptable. Here, asynchronous replication helps scale writes and reduce user-facing latency without overengineering the system.

Things get even trickier during network partitions or crash recovery. In a synchronous setup, if a replica becomes unreachable, the system might block writes to avoid inconsistency. That protects correctness but hurts availability. In an asynchronous setup, the primary can keep accepting writes, but replicas may fall behind. When they rejoin, the system has to reconcile differences, which need to be carefully managed.

There’s no perfect choice.

Synchronous replication prioritizes correctness but risks availability.

Asynchronous replication favors speed and uptime, but at the cost of potential data loss during failure.

Choosing between them depends on what the system values most: durability, consistency, latency, or availability. The architecture has to reflect that priority clearly.

Database Replication Strategies

Let us now look at the main types of data replication strategies or architectures. For each type, we will also understand how data is propagated, typical use cases, failure scenarios, and trade-offs.

1 - Single-Leader Replication

Single-leader replication, often called primary-replica replication, is the most widely used strategy.

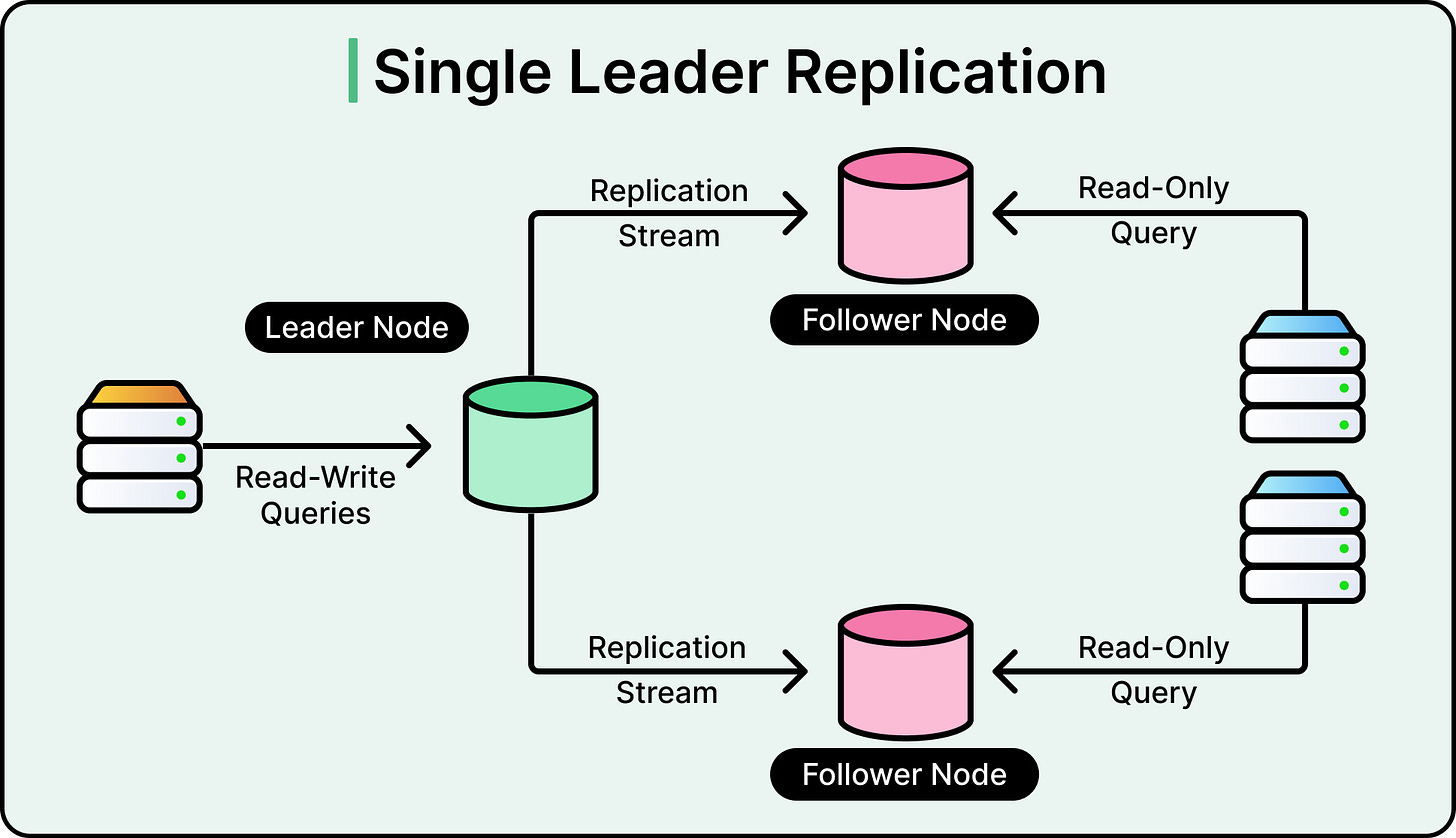

It works on a straightforward idea: one node, the leader, handles all write requests. All other nodes, known as followers or replicas, copy the leader’s data changes and apply them to their local state. Reads can go to the leader or the replicas, depending on the consistency requirements of the application. See the diagram below:

This model keeps write coordination simple. There’s no ambiguity about which node accepts the write requests. It also allows enforcing ordering, resolving conflicts deterministically, and preserving transactional guarantees like foreign keys or row-level locks.

Replication between the leader and replicas typically happens through write-ahead log (WAL) shipping or similar replication logs. Every change the leader makes (insert, update, delete) is first written to a durable log. That log is then streamed or copied to the replicas. Replicas replay the log entries to apply the same changes in the same order.

This log-based replication ensures replicas converge toward the leader’s state, even if there is a brief delay.

For read scalability, single-leader replication works well. Since only the leader handles writes, the replicas are free to serve read queries. This is especially useful in read-heavy applications. However, reads from replicas can return stale data due to replication lag. Applications that require strict read-after-write consistency must either route all reads to the leader or implement logic to detect lagging replicas.

Failover is the critical operational challenge in single-leader setups. When the leader goes down, the system needs to promote one of the replicas to be the new leader. This process involves multiple steps, such as:

Detecting that the current leader is unreachable.

Selecting a healthy, up-to-date replica.

Promoting it to the leader.

Reconfiguring clients and replicas to point to the new leader.

2 - Multi-Leader Replication

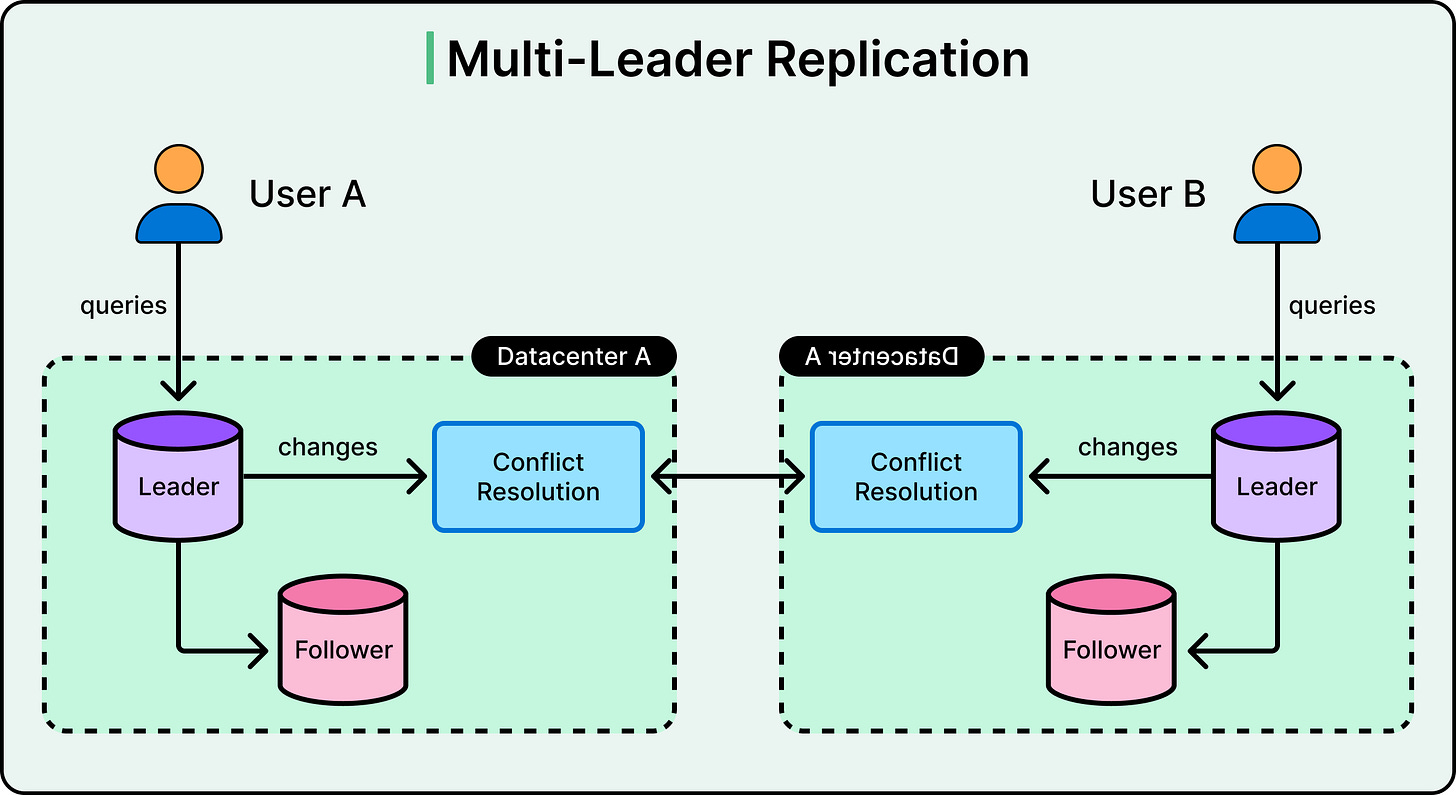

Multi-leader replication allows multiple nodes to accept writes independently.

Each node operates as both a leader and a replica. It processes local writes and also receives changes from other leaders. The nodes replicate to each other in a peer-to-peer fashion, either directly or through a mesh or hub-and-spoke topology.

See the diagram below:

This architecture improves write availability, especially in geographically distributed systems. If users in different regions write to their local database nodes, multi-leader replication avoids the round-trip latency to a distant primary. Even if one region goes offline, local writes can continue. This is useful in collaboration apps, mobile sync platforms, or systems with offline modes that must merge changes later.

However, removing a single source of truth introduces new complexity.

The key challenge in multi-leader systems is conflict resolution. When two leaders accept writes to the same record before syncing with each other, the system must decide how to merge those changes. Without a consistent resolution strategy, data can diverge or become corrupt.

Some common conflict resolution strategies include:

Last-write-wins (LWW): Each write carries a timestamp, and the most recent one overwrites earlier changes. This is simple but can silently drop updates if clocks are skewed or if concurrent changes happen.

Custom merge logic: The application defines how to combine conflicting updates. This can involve merging lists, summing counters, or applying domain-specific rules. It's more accurate but requires case-by-case design.

Version vectors or CRDTs (Conflict-free Replicated Data Types): These track causality and allow automatic, mathematically safe merges for certain data types.

Even with conflict resolution in place, write skew remains a risk. This happens when two valid updates, applied independently, break an invariant when merged. For example, two users booking the last seat on a flight from different leaders might both succeed locally. When the system reconciles, it ends up with an overbooked flight.

Despite the complexity, multi-leader replication is useful in specific contexts:

Mobile apps with offline write support and background sync.

Cross-region systems where write latency is critical.

Edge deployments with poor or intermittent connectivity.

However, it’s not a general-purpose solution. It can add operational burden, risks silent data corruption if conflicts are mishandled, and often limits the types of guarantees that can be safely offered.

3 - Leaderless Replication

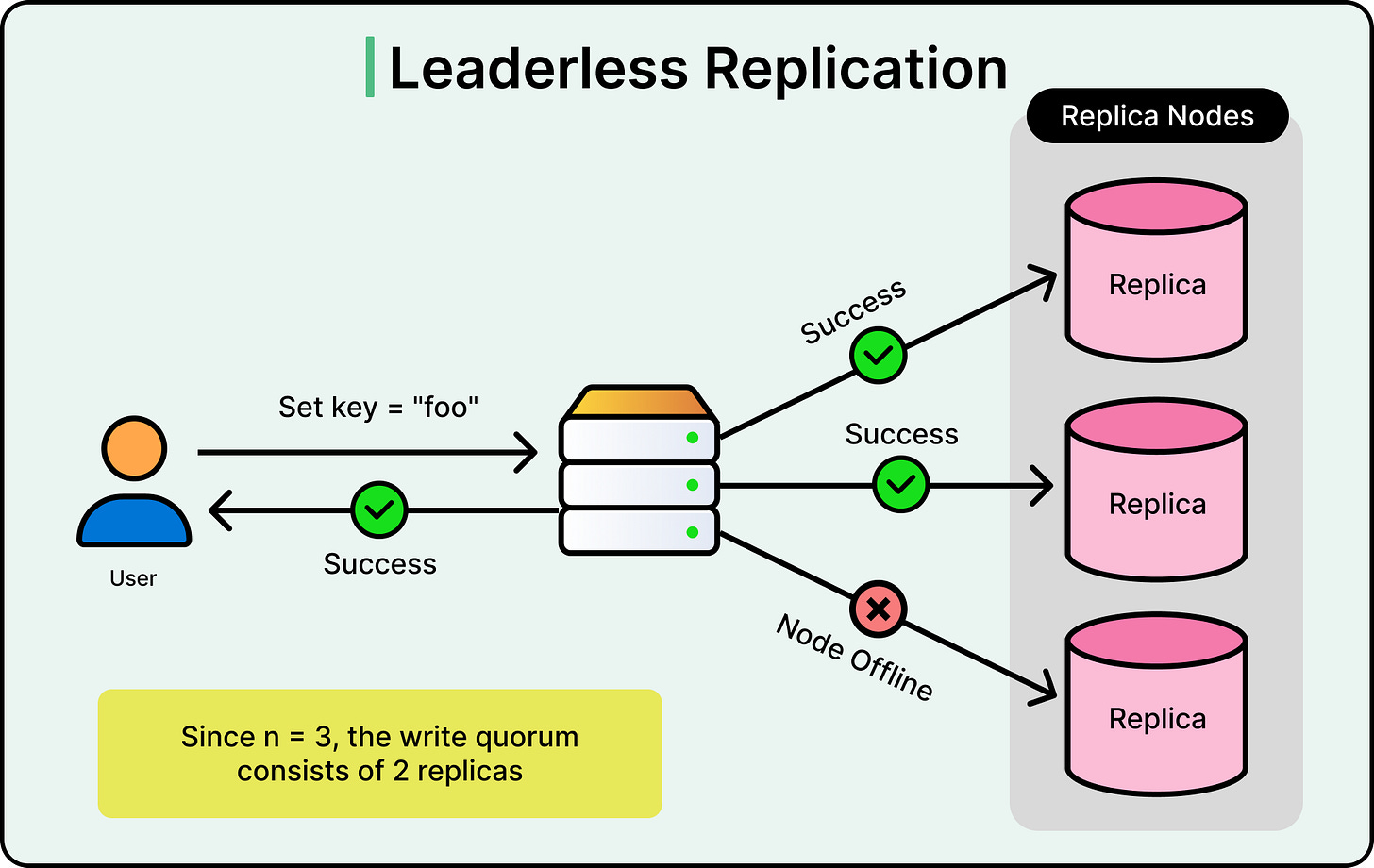

Leaderless replication takes a different path. Instead of designating one node as the source of truth, all nodes are peers. Any node can accept reads or writes. Coordination happens at the client level or through a coordination layer that understands how to reach consensus across multiple replicas.

This model was popularized by systems like Amazon Dynamo, which prioritized availability and partition tolerance over strict consistency. The key idea is that data gets written to multiple nodes in parallel, and the system considers the write successful once a certain number of nodes have acknowledged it. The same goes for reads.

This brings us to the idea of quorum-based replication, defined by three parameters:

N: The total number of replicas for a piece of data

W: The number of replicas that must acknowledge a write

R: The number of replicas that must participate in a read

To ensure consistency, the system aims for W + R > N. This guarantees that at least one node in the read quorum has seen the most recent write. For example, if N = 3, setting W = 2 and R = 2 ensures overlap. If W + R is less than or equal to N, stale reads become possible.

See the diagram below that shows leaderless replication.

Because any node can fail or become temporarily unreachable, leaderless systems must handle partial availability. If a node is down during a write, the system uses techniques such as hinted handoff. This technique involves temporary storage of the write on another node, which will later replay it to the intended recipient once it's back online.

Over time, inconsistencies can still build up between replicas. To fix this, systems run background processes like anti-entropy repair, which compare data across nodes and reconcile differences. Merkle trees or similar structures are often used to efficiently detect divergent data.

Leaderless replication offers significant benefits such as:

High availability even during network partitions or node failures.

Write flexibility without a central coordination bottleneck.

Resilience to hardware outages and datacenter-level faults.

However, the strategy also comes with real complexity. Clients must be smart enough to coordinate reads and writes. Handling conflicting writes becomes challenging, especially under concurrent updates. Systems often need vector clocks or conflict resolution logic to make sense of divergent versions. Write amplification can be another issue because every update touches multiple nodes, consuming bandwidth and storage.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at database replication in detail, along with various strategies, approaches, and the impact of replication lag.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Database Replication is the foundation for building highly available, resilient, and low-latency data systems.

Replication can introduce lag between when data is written to a leader and when it appears on replicas. This lag can cause stale reads, break consistency guarantees, and surprise users and developers alike.

Consistency in replicated systems is a trade-off. Systems must balance latency, durability, and correctness.

Synchronous replication waits for replicas before acknowledging a write, improving durability and consistency at the cost of latency. Asynchronous replication returns immediately, favoring speed but risking data loss during failures.

Single-leader replication funnels all writes through a single node. Replicas follow that node by replaying a write-ahead log. It simplifies coordination, scales read requests, and is easy to reason about, but it also introduces a single point of failure and a potential bottleneck for writes.

Multi-leader replication allows multiple nodes to accept writes independently, improving availability and local write performance. However, it complicates conflict resolution and consistency, requiring custom merge logic or version tracking.

Leaderless replication, as seen in systems like Amazon Dynamo, uses quorum-based coordination across peer nodes. Clients write to and read from configurable numbers of replicas.

No replication strategy is universally best. Each approach involves trade-offs in latency, availability, consistency, and operational simplicity. Choosing the right strategy depends on the system’s priorities and failure tolerance.

Understanding these replication models and their behaviors under real-world conditions is essential to designing systems that survive outages, scale gracefully, and serve users reliably.

This is perfect summary of "Replication" chapter from Klepmann's DDIA book.