As usage grows and features pile on, applications begin generating more data, often by the hour. That’s a healthy sign for the business. But architecturally, it raises a red flag: the database starts showing strain.

The database sits at the core of nearly every system. Reads, writes, and updates funnel through it. However, unlike stateless services, databases are notoriously hard to scale horizontally. CPUs and memory can be upgraded, but at some point, a single instance, no matter how powerful, becomes the bottleneck. Response times degrade, and queries can time out. Replicas fall behind. Suddenly, what worked at 10,000 users breaks at 10 million.

This is where sharding enters the picture.

Sharding splits a large database into smaller, independent chunks called shards. Each shard handles a subset of the data, allowing traffic and storage to scale out across multiple machines instead of piling onto one.

But sharding is a major shift with real consequences. Application logic often needs to adapt. Query patterns change, and joins become harder. Transactions span physical boundaries. There’s overhead in managing routing, rebalancing, and failover.

This article looks at the fundamentals of database sharding. We cover details like why it matters, how it works, and what trade-offs come with it. We’ll walk through common sharding strategies and practical engineering considerations.

What is Sharding?

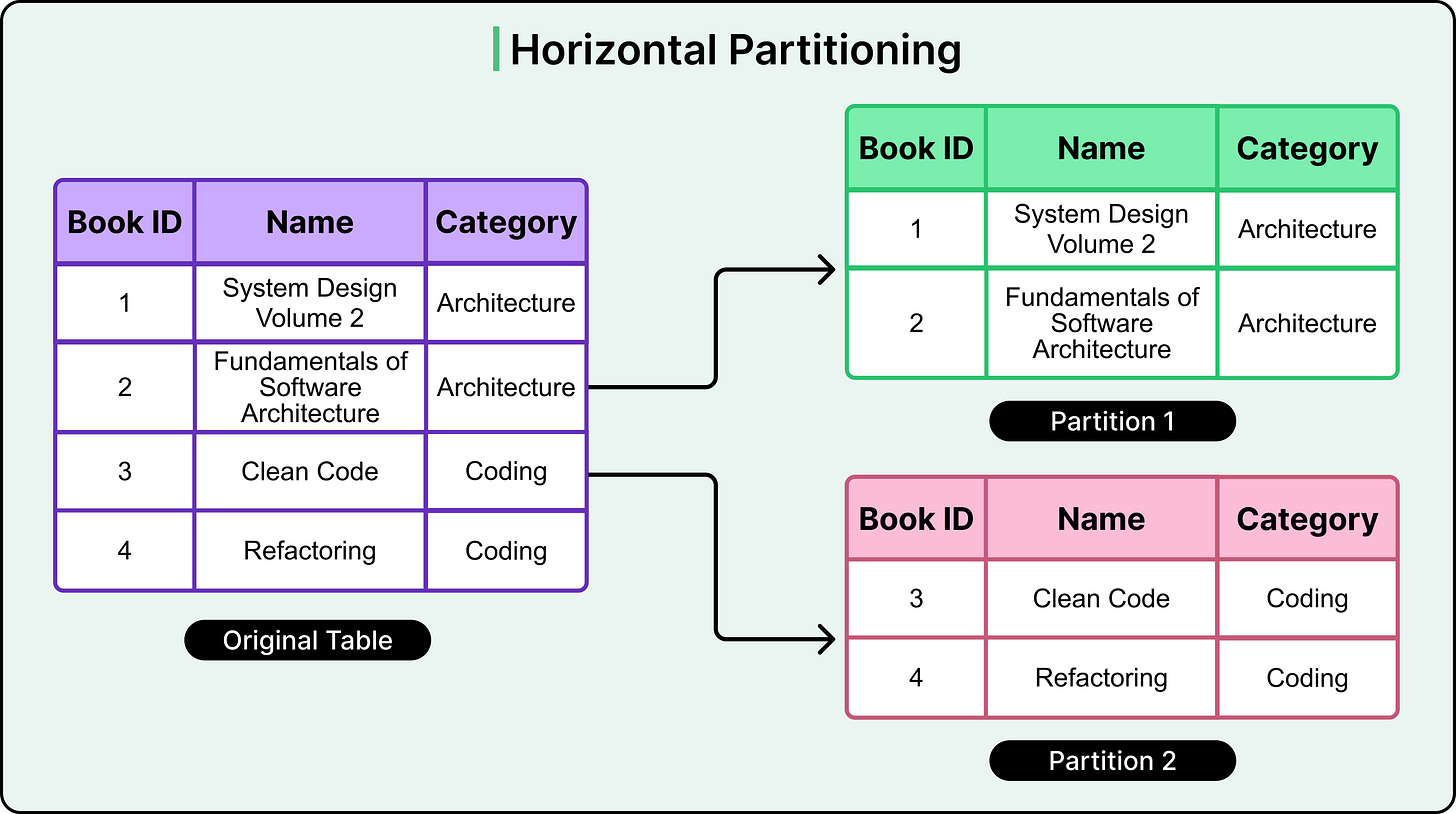

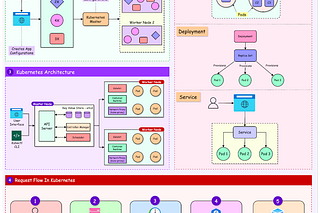

Sharding is a database architecture pattern designed to handle large datasets by splitting them into smaller, more manageable pieces. At its core, it builds on horizontal partitioning: a technique where rows from a table are divided across multiple partitions, each holding a subset of the data. See the diagram below for a simple example:

However, traditional horizontal partitioning keeps all partitions on the same physical machine. This helps with organizing data, but doesn’t solve for hardware limits.

Sharding takes this a step further. It distributes those partitions across multiple machines or nodes. Each shard holds a portion of the dataset and operates independently, allowing the system to scale out as data volume and query load grow.

This distribution provides two critical benefits:

Scalability: By spreading data across nodes, storage and compute capacity increase linearly with the number of shards.

Isolation of load: Heavy queries on one shard don’t impact others, which improves overall system responsiveness.

Sharding typically involves more than just cutting tables into pieces. It requires routing logic to determine where a particular piece of data lives, coordination between shards for cross-shard operations, and sometimes even rebalancing when data skews unevenly.

Types of Sharding

The goal of sharding is simple: distribute both data and query load evenly across multiple nodes. However, in practice, getting that balance right is far from trivial.

When data isn’t partitioned thoughtfully, some shards end up doing more work than others. One shard might handle most of the queries or store far more records than the rest. This is called shard skew, and it reduces the benefits of sharding. Latency creeps up, some nodes sit idle, and scaling becomes uneven.

In the worst-case scenario, a single shard absorbs the majority of traffic. That shard becomes a hot spot while the others remain underutilized. These hot spots usually appear when the sharding key has poor cardinality or correlates too strongly with access patterns. For example, sharding by country code might send all U.S. traffic to a single node, swamping it while other regions see barely any load.

Avoiding these pitfalls requires choosing a sharding strategy that distributes both storage and read/write operations evenly. That choice often depends on the access patterns of the application, the shape of the data, and how the system needs to evolve.

Let’s look at a few sharding strategies in detail:

Range-Based Sharding

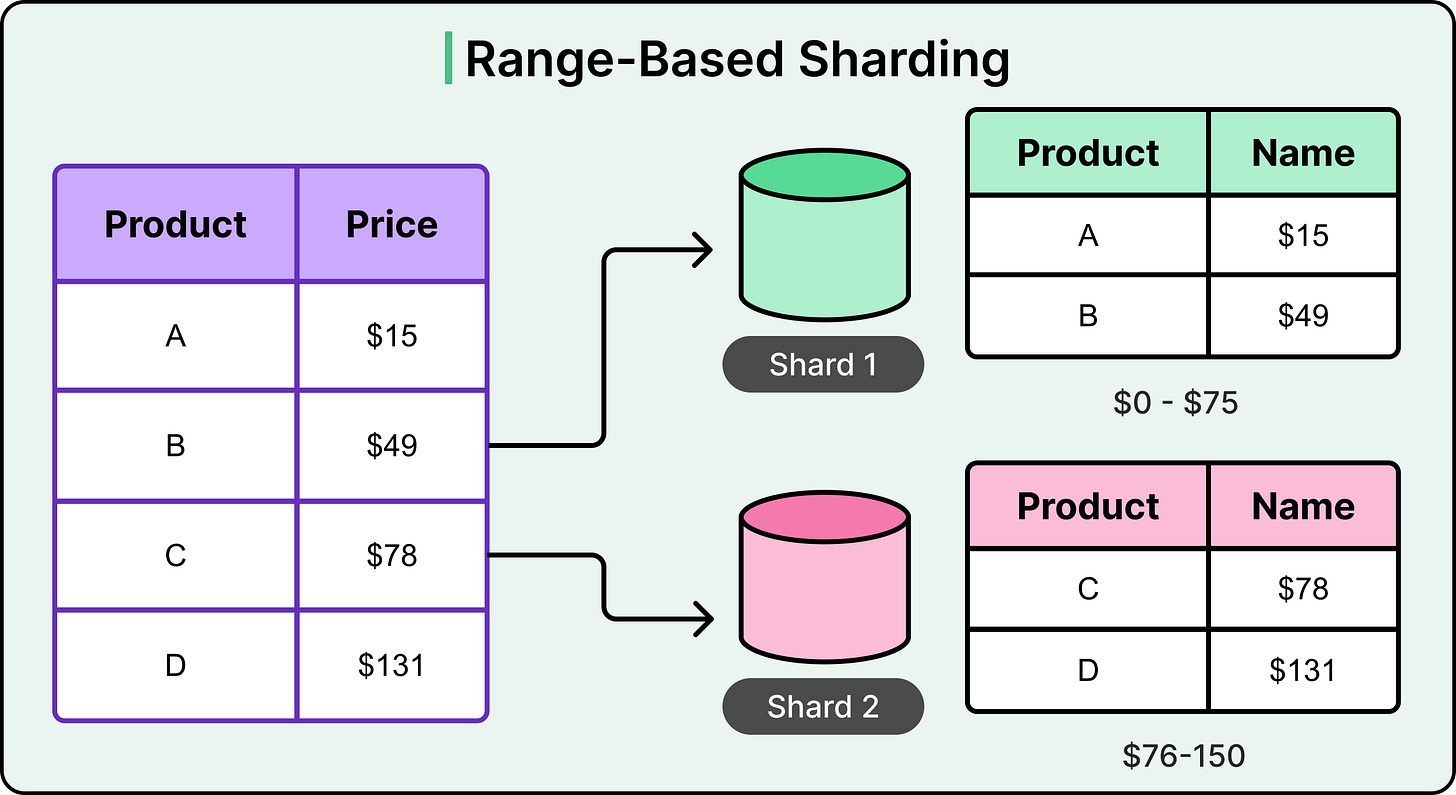

Range-based sharding divides data by splitting it across shards based on contiguous ranges of a sharding key. Each shard owns a specific range, defined by minimum and maximum key values. This setup works well when queries often target ordered or sequential data.

For example, consider a product catalog. If products are sharded by price, one shard might hold all items priced between 0 and 75, another between 76 and 150, and so on. Because data is stored in sorted order within each shard, range queries like "find all products under 100 dollars" can be executed efficiently, often requiring only a single shard scan.

This strategy works well when:

Queries frequently filter by a continuous key (for example, time, price, score, etc).

The sharding key has a natural ordering that matches common access patterns.

Efficient range scans are more valuable than fully parallel lookups.

However, the distribution of data isn’t always uniform. Real-world datasets often skew. For example, some key ranges may have far more records than others. If too many entries fall into the same range, one shard starts handling the bulk of reads and writes. This results in a hot spot, where one node is overwhelmed while others are underutilized.

Range-based sharding is also brittle in systems where access patterns evolve. A time-series application might shard by timestamp, but if most queries target recent data, the latest shard carries almost the entire load.

To prevent imbalance, the developers should do the following:

Analyze data distribution regularly.

Adjust range boundaries dynamically, though this requires resharding and data migration.

Avoid low-cardinality sharding keys or those likely to create temporal skew.

Hash or Key-Based Sharding

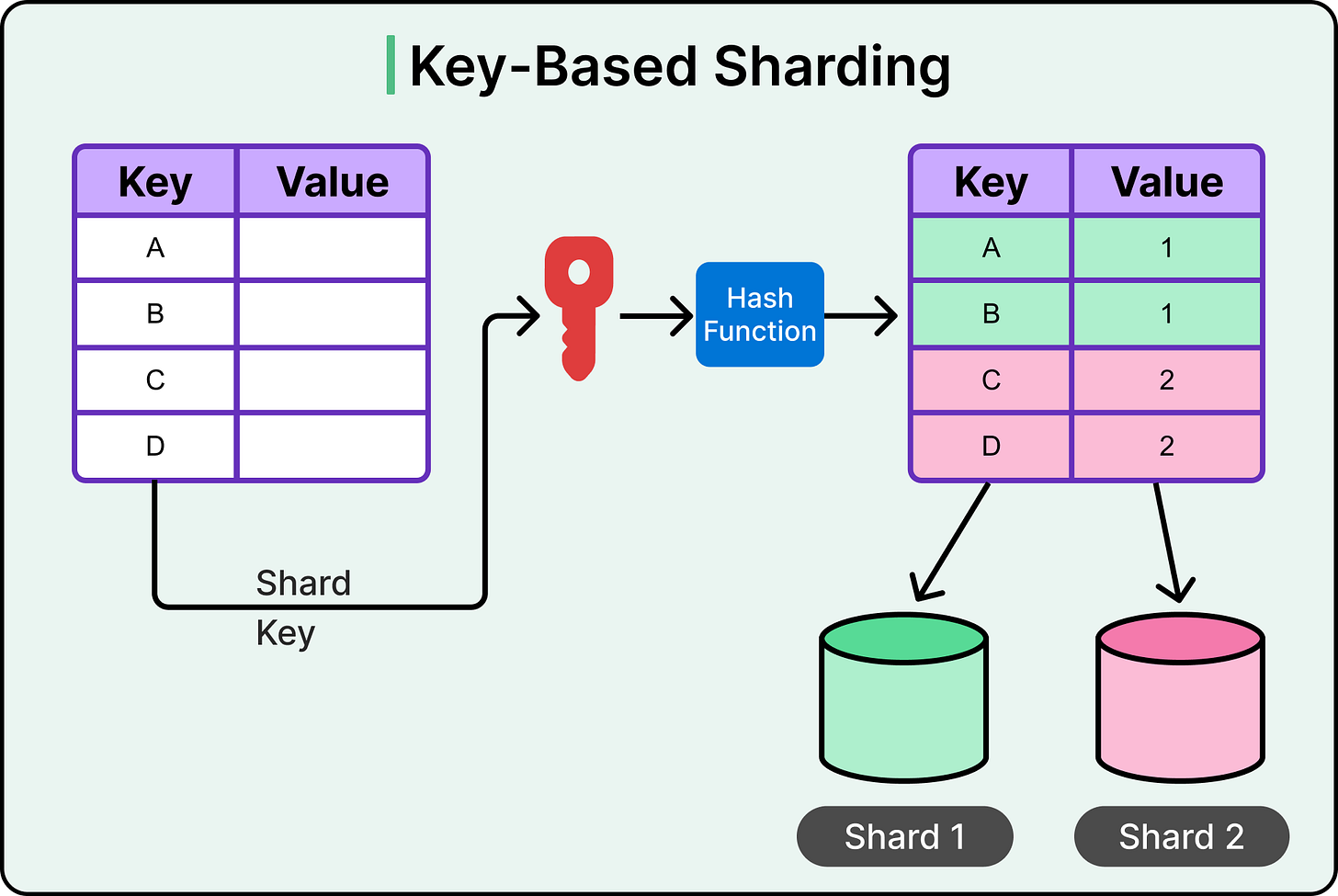

Key-based sharding, often called hash-based sharding, uses a hash function to determine where a given record should live.

Instead of dividing data by key ranges, this approach applies a hash function to a chosen key (such as user ID, product ID, or email) and assigns the result to a shard. See the diagram below for an example:

Each shard owns a subset of the hash space. When a request comes in, the system hashes the key and routes the operation to the corresponding shard. This mechanism helps spread data evenly across the cluster, especially when the hash function is well-designed and the input keys are diverse.

The main benefit of this strategy is its ability to reduce the risk of hot spots.

Since the mapping is based on hash values rather than sequential or semantically meaningful ranges, adjacent keys get scattered. As a result, no single shard handles a disproportionate amount of traffic under normal conditions.

Hash-based sharding works well when:

The key space is large and unpredictable.

The system requires uniform load distribution across shards.

The majority of access patterns are point lookups rather than range scans.

However, this comes with a trade-off. Since keys are no longer stored in any meaningful order, range queries become inefficient. To fetch a sequence of records, the system must broadcast the query to all shards and aggregate the results, which increases latency and load.

It's also important to recognize that hash-based sharding doesn’t eliminate hot spots. If a particular key is disproportionately popular, such as a celebrity's user ID on a social platform, all reads and writes still land on the same shard. The hashing logic distributes keys evenly, but it cannot redistribute access patterns that are already uneven.

Directory-Based Sharding

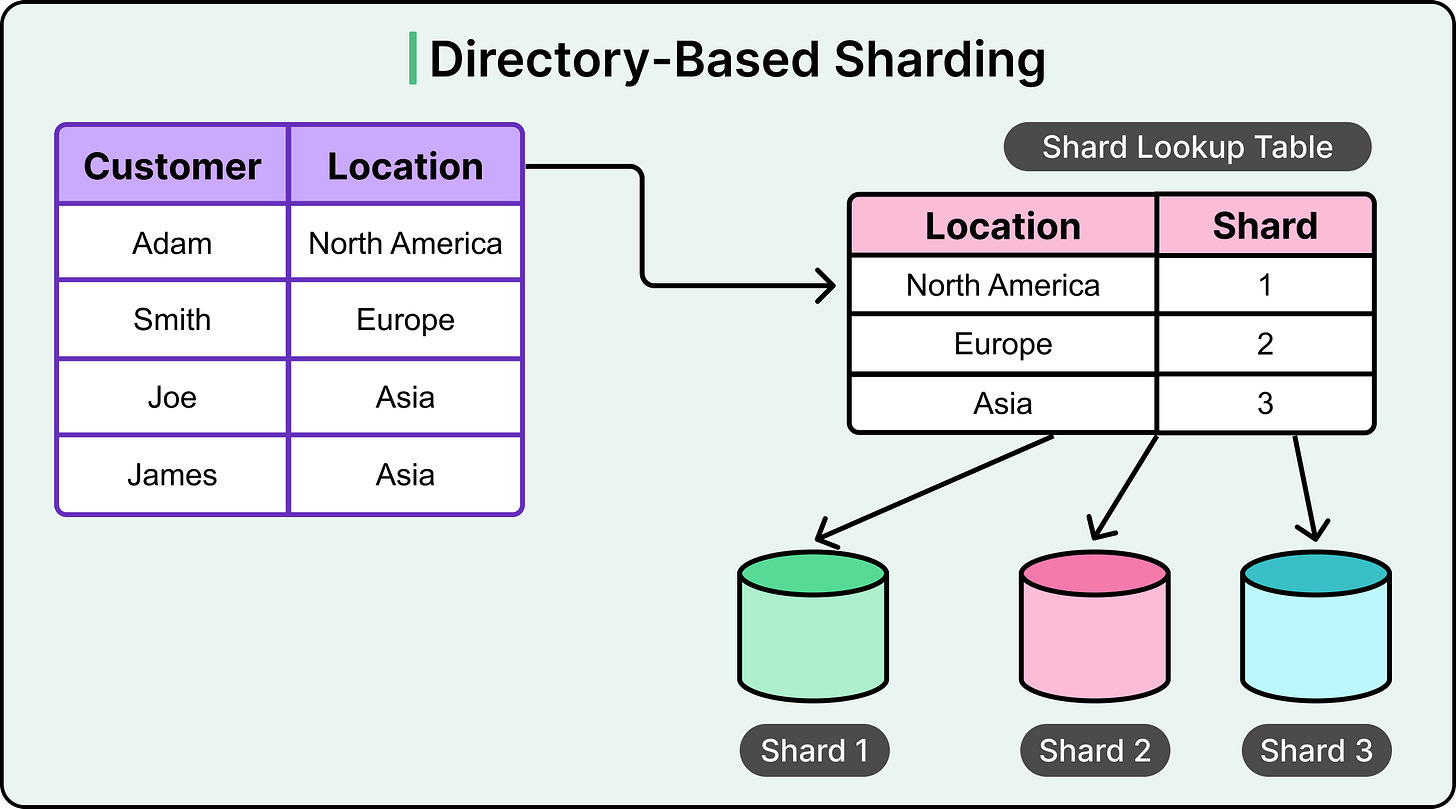

Directory-based sharding uses a central lookup table to map each record to its corresponding shard. Instead of relying on ranges or hash functions, this approach maintains an explicit directory that links a shard key to the exact shard where the data lives.

Think of the lookup table as a routing index. For every key, it stores the shard location, allowing the application or middleware to route queries and updates accurately. This gives the system full control over where each piece of data goes, independent of key distribution or hash outcomes.

The main advantages of this approach are as follows:

Data can be distributed based on custom logic, including business rules, geo-affinity, or usage patterns.

It's easy to move records between shards by simply updating the lookup table.

Shard sizes can be manually balanced without rewriting sharding logic or changing keys.

Directory-based sharding works well when:

The dataset is highly skewed and needs custom placement.

Shard sizes must be actively monitored and rebalanced.

Business logic dictates data locality, such as storing European customers in EU data centers.

However, the flexibility comes at a cost.

The lookup table can become a critical dependency. Every read or write must consult the directory to determine the correct shard. If the table becomes a bottleneck or goes down, the entire routing process breaks. Also, changes to the sharding map need coordination to ensure consistency across the system.

In summary, directory-based sharding gives precise control over data placement, which is invaluable in complex or high-skew systems. However, it centralizes routing logic in a way that can threaten reliability and performance if not carefully managed. Systems using this approach must invest in making the lookup infrastructure highly available, fast, and resilient.

Selecting a Shard Key

The effectiveness of a sharding strategy depends heavily on the shard key. It controls how data is split across shards, how evenly the system handles load, and how efficiently queries are routed. A poor choice of shard key can introduce hot spots, uneven growth, or operational complexity.

Here are three key factors to evaluate when selecting a shard key:

Cardinality

Cardinality refers to the number of distinct values a field can take. It determines how finely data can be distributed across shards.

Low-cardinality keys, such as boolean fields or enums with few values, severely limit distribution. For example, using a "gender" field or a "status" field with values like "active" or "inactive" results in only a handful of shards, regardless of dataset size.

High-cardinality keys, like user IDs, email addresses, or UUIDs, offer greater flexibility. They enable fine-grained distribution, making it easier to avoid hot spots and scale horizontally.

High cardinality does not guarantee a balanced system, but low cardinality almost always creates load concentration.

Frequency

Frequency measures how often each shard key value appears in the dataset. Even with high cardinality, data can still skew if a small subset of key values dominates.

If 60 percent of queries hit only 10 percent of the keys, the shards responsible for those keys will carry most of the load.

For example, if a fitness app shards users by age and most subscribers fall between 30 and 45, the shard holding that age group will become overloaded, while others stay idle.

Selecting a key with both high cardinality and uniform frequency across values improves the chance of even distribution. Sampling the data beforehand often helps expose hidden skewness.

Monotonic Change

Monotonic change refers to how a key’s value evolves. When shard keys follow a predictable upward or downward trend (like timestamps, auto-increment IDs, or activity counters), they create uneven growth across shards.

A comment system that shards by the number of user comments might initially distribute data evenly. However, over time, active users drift toward shards with higher comment thresholds. This results in older shards growing stale while one shard absorbs nearly all new writes.

Time-based keys often produce similar patterns. If each day's data goes into a new shard, the latest shard receives all traffic while older ones are idle.

To prevent this, avoid using monotonically increasing keys unless range-based access is essential and hot shards can be rotated or offloaded. In write-heavy systems, static or random keys offer more stability over time.

Rebalancing the Shards

As a system scales, workloads shift. Some shards grow faster than others, and query volume increases unevenly. Machines can also fail, or new nodes may be added. Over time, the original distribution of data no longer reflects the current state of the system.

To keep performance stable and resource usage balanced, the cluster must redistribute both data and traffic. This process is called shard rebalancing.

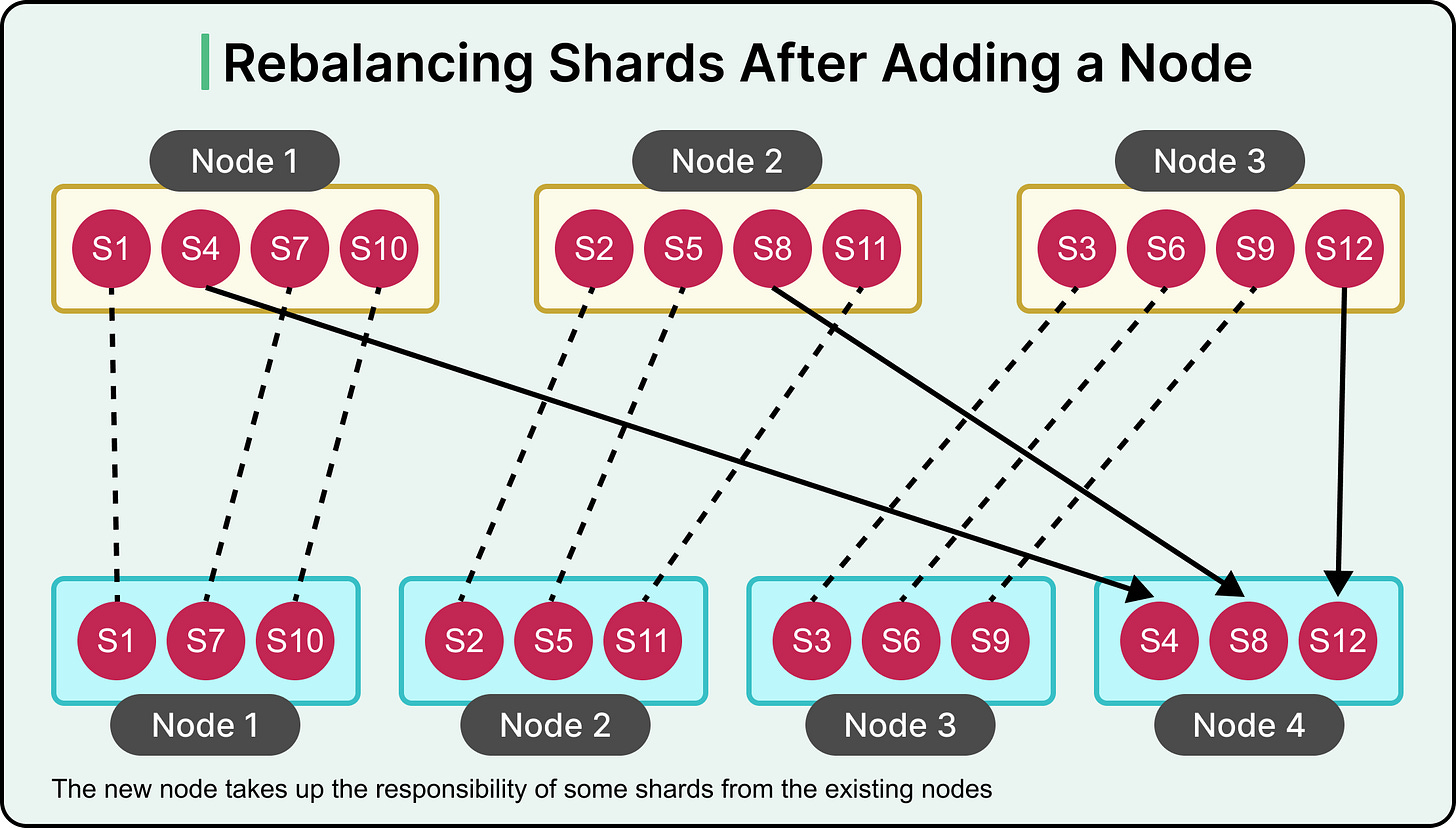

See the diagram below that shows how the addition of a newe can result in rebalancing the shards.

Rebalancing serves three primary goals:

Fair load distribution: After rebalancing, no single node should carry significantly more data or handle more queries than the rest.

Minimal disruption: The system must continue serving reads and writes while shards are being moved.

Efficient data movement: The amount of data transferred across nodes should be minimized to avoid long migration windows and network strain.

There are multiple ways to implement rebalancing. One common approach is to use a fixed number of shards, set at the time of system initialization.

Fixed Number of Shards

In this model, the total number of shards is predetermined and does not change, even if the number of physical nodes changes.

For example, a database might be configured with 100 shards running across 10 nodes, with each node responsible for 10 shards. If a new node joins the cluster, the system redistributes some of the existing shards to the new node, balancing the overall load.

Key characteristics of this model:

The shard-to-key mapping remains constant. There is no change in how keys are hashed or routed.

Entire shards are moved during rebalancing. Individual records are not split or re-partitioned.

Rebalancing only involves updating the placement of shards across nodes, not modifying the internal sharding logic.

This model keeps routing logic simple and deterministic, since each key always maps to the same shard. The trade-off lies in choosing the right number of shards up front.

Dynamic Shards

Dynamic sharding allows the number of shards in a database to grow or shrink based on the total volume of data. Instead of committing to a fixed shard count at setup, the system adjusts its partitioning strategy as the dataset evolves.

When data volume is low, the system maintains fewer shards. This keeps management overhead minimal, reduces inter-shard coordination, and simplifies routing logic. However, as the dataset grows, the system automatically adds new shards to maintain performance and avoid overloading any single node.

Most implementations define a maximum size per shard, often based on disk usage or performance thresholds. Once a shard crosses that limit, the system splits it or creates new ones and redistributes data accordingly.

Dynamic sharding offers two key advantages:

Scalability without upfront decisions: There’s no need to guess the future size of the system during initial configuration.

Adaptability to growth: As storage and traffic increase, the system can respond by expanding the shard pool incrementally.

This model works with both range-based and hash-based sharding:

In range-based systems, dynamic sharding might split an overloaded key range into two or more sub-ranges and assign each to a new shard.

In hash-based systems, the hash space can be divided into finer segments as the load increases, similar to consistent hashing with virtual nodes.

Request Routing in a Sharded Database

Once a dataset is sharded, routing requests to the correct node becomes one of the most critical problems to solve.

A single query might need to touch a specific shard. A write must land on the node that owns the relevant data. If the system gets this wrong, performance suffers, or data ends up in the wrong place.

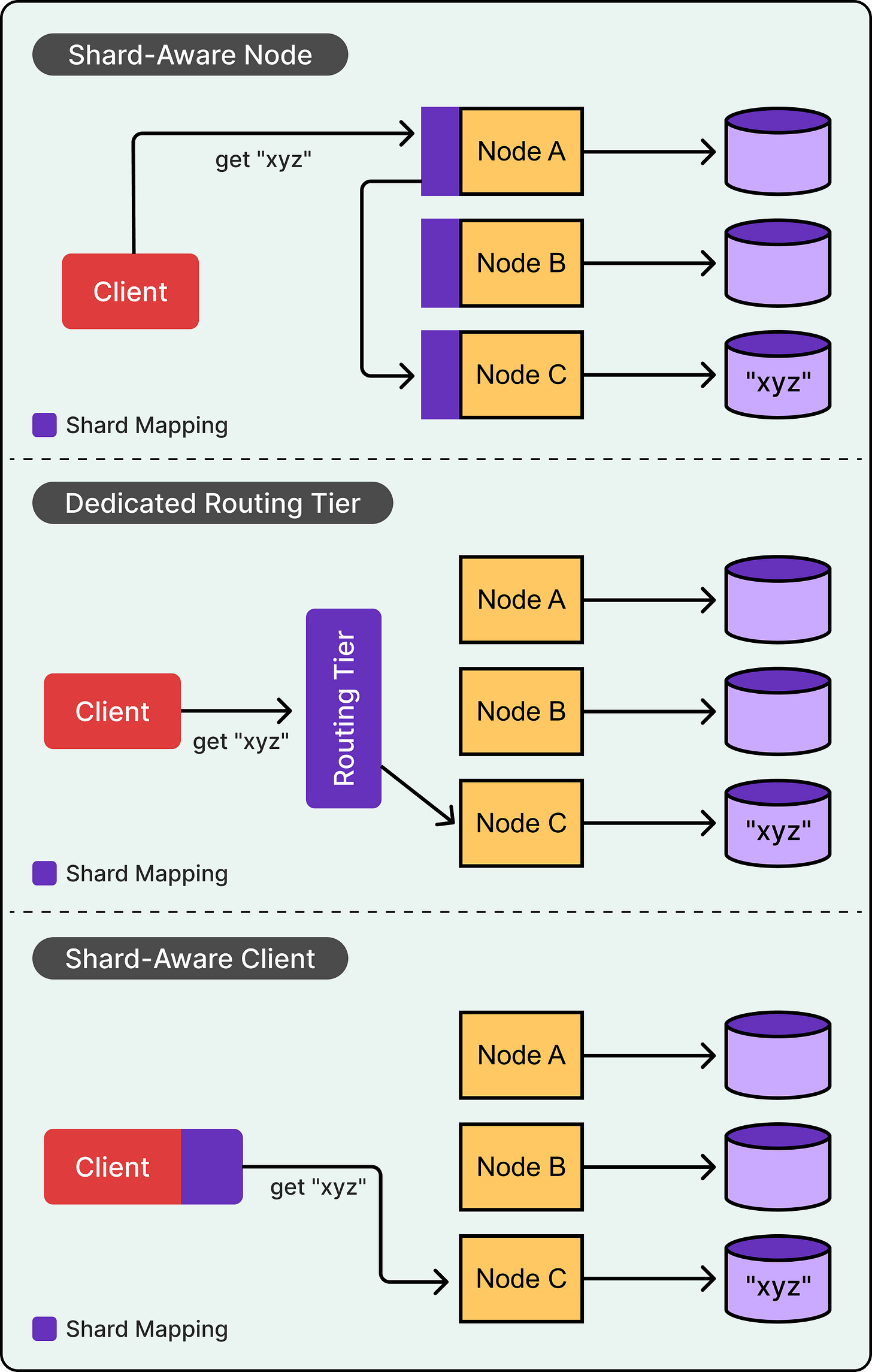

There are three common strategies to route requests in a sharded database:

Shard-Aware Node: In this model, any client request can hit any node in the cluster. The client connects through a load balancer that spreads traffic across all nodes, often using round-robin or another simple strategy. Each node knows the full mapping of shard-to-node assignments. If it receives a request for data it owns, it handles the request locally. If not, it forwards the request to the correct node internally and relays the response back to the client.

Routing Tier: Here, a dedicated routing layer sits between clients and the database nodes. The routing tier maintains the full shard map and directs each request to the correct node based on the shard key. Clients always talk to the router, and the router always knows where to send the request. This is common in systems like MongoDB, where the router tier (mongos) handles all routing decisions.

Shard-Aware Client: In this model, the client is responsible for determining which node to talk to. It either maintains a copy of the shard map locally or queries a metadata service to retrieve it. Once it knows the shard assignment for a given key, it connects directly to the right node. This approach removes any intermediate routing hop and is highly efficient for systems where clients are capable of maintaining state.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at database sharding and its various strategies in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Sharding is a horizontal scaling technique that partitions data across multiple nodes to prevent the database from becoming a bottleneck.

It builds on horizontal partitioning but distributes data across machines, not just within one.

The primary goal of sharding is to spread data and query load evenly; imbalance leads to shard skew or hot spots.

Range-based sharding divides data by key ranges and is efficient for range queries, but risks hot spots if data distribution is uneven.

Hash-based sharding uses a hash of the shard key to distribute data uniformly, but sacrifices the ability to run efficient range queries.

Directory-based sharding uses a central lookup table to map keys to shards, offering maximum control at the cost of increased complexity and a single point of failure.

A good shard key often has high cardinality, even frequency distribution, and minimal monotonic change to avoid imbalance and future rebalancing pain.

Shard rebalancing is essential to maintain even workload distribution as data volume and node count change.

Fixed shard models use a predefined number of partitions, moving entire shards between nodes during rebalancing while keeping the key-to-shard mapping stable.

Dynamic sharding increases or splits shards as data grows, allowing the system to scale naturally but requiring more automation and careful coordination.

Routing requests in a sharded system can be handled by shard-aware nodes, a dedicated routing tier, or shard-aware clients.

1. Consistent hashing is worth mentioning

2. It would be nice to add what strategies are used in popular solutions; only MongoDB is mentioned