Modern applications don’t operate in a vacuum. Every time a ride is booked, an item is purchased, or a balance is updated, the backend juggles multiple operations (reads, writes, validations) often across different tables or services. These operations must either succeed together or fail as a unit.

That’s where transactions step in.

A database transaction wraps a series of actions into an all-or-nothing unit. Either the entire thing commits and becomes visible to the world, or none of it does. In other words, the goal is to have no half-finished orders, no inconsistent account balances, and no phantom bookings.

However, maintaining correctness gets harder when concurrency enters the picture.

This is because transactions don’t run in isolation. Real systems deal with dozens, hundreds, or thousands of simultaneous users. And every one of them expects their operation to be successful. Behind the scenes, the database has to balance isolation, performance, and consistency without grinding the system to a halt.

This balancing act isn’t trivial. Here are a few cases:

One transaction might read data that another is about to update.

Two users might try to reserve the same inventory slot.

A background job might lock a record moments before a customer clicks "Confirm."

Such scenarios can result in conflicts, race conditions, and deadlocks that stall the system entirely.

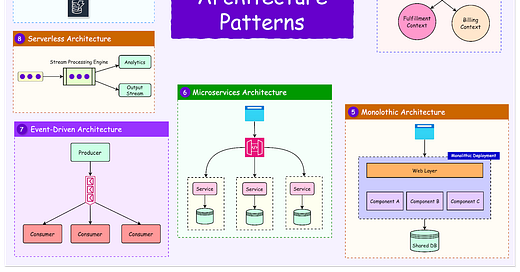

In this article, we break down the key building blocks that make transactional systems reliable in the face of concurrency. We will start with the fundamentals: what a transaction is, and why the ACID properties matter. We will then dig deeper into the mechanics of concurrency control (pessimistic and optimistic) and understand the trade-offs related to them.

What is a Database Transaction?

A transaction is the database’s answer to a fundamental problem: how to guarantee correctness when multiple operations need to act as a single unit.

Think of it as a contract. Either everything in the transaction happens, or nothing does.

At its core, a transaction is a bundle of read and write operations treated atomically. This might mean debiting one account and crediting another in a fund transfer, or updating inventory and logging an order when a customer checks out. In both cases, doing only part of the work (like debiting an account but failing to credit the other) leaves the system in a broken state. Transactions prevent that.

Most relational databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server) treat transactions as first-class primitives. Non-relational systems such as MongoDB or Apache Cassandra may offer transactional guarantees as well, though often with caveats around scope (for example, document-level versus multi-document).

Regardless of the model, the idea stays the same: all-or-nothing state changes, ideally with isolation from other concurrent changes.

The Transaction Lifecycle

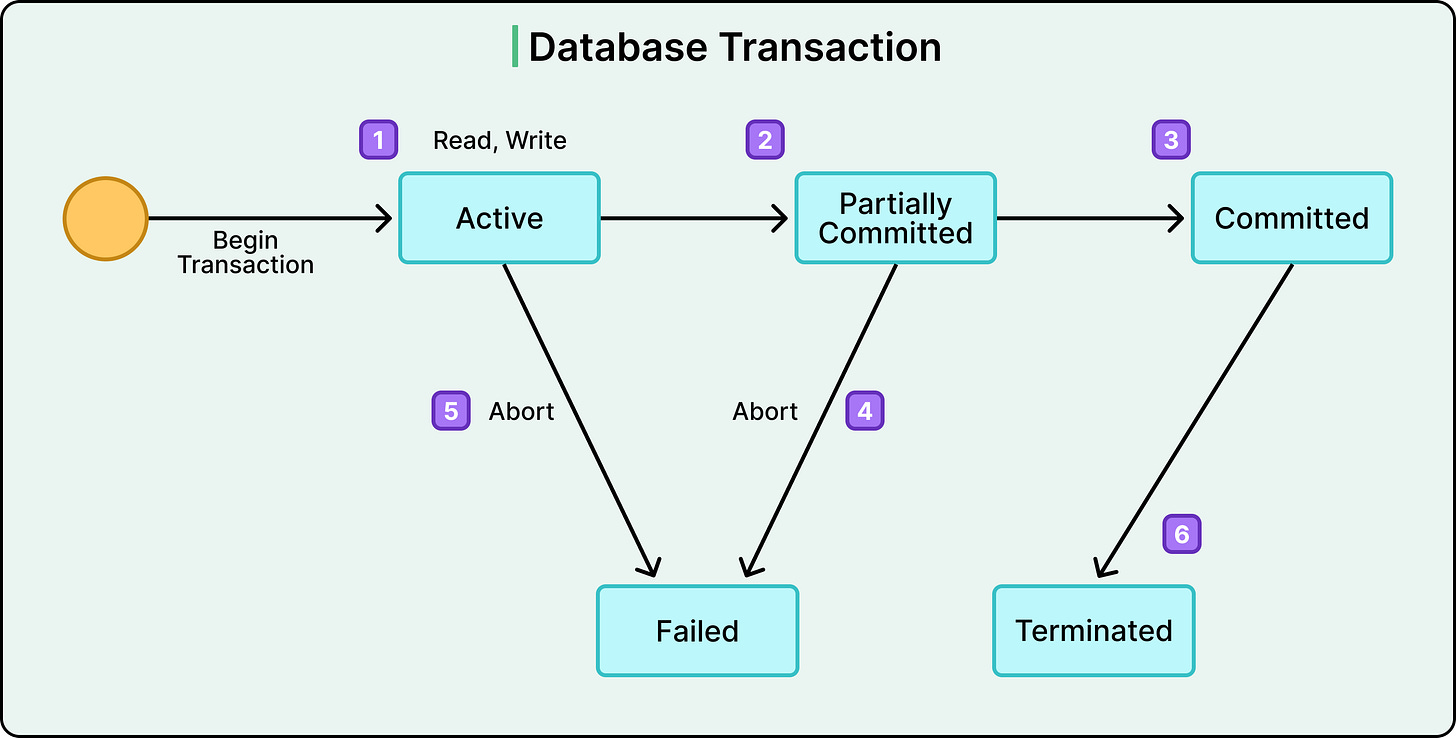

Transactions follow a predictable lifecycle with some key stages:

BEGIN: The database starts tracking changes.

READ/WRITE: The transaction performs its work (queries, updates, inserts, deletes).

COMMIT: If everything looks good, the changes are finalized and made visible.

ROLLBACK: If something fails due to an error, a constraint violation, or an explicit abort, then all changes are undone.

See the diagram below that shows the high-level stages in a typical transaction lifecycle.

The database engine uses internal mechanisms like write-ahead logs or undo buffers to ensure that rollback and commit are reliable, even during power loss or crash recovery.

This lifecycle gives developers a clean mental model: wrap related operations in a transaction block, and either get a consistent result or a clean failure.

Transactions in Concurrent Systems

The real challenge is running transactions concurrently without introducing subtle bugs.

Databases rarely run transactions one after the other. Doing so would kill throughput. Instead, they interleave reads and writes from multiple transactions to keep the system responsive. But when operations overlap on the same data, things get tricky.

Imagine a ride-hailing app where two drivers accept the same request at the same moment. Without isolation, both transactions could see the ride as unassigned and confirm it. Or consider an analytics platform where one process updates a record while another reads it halfway through. Without consistency, the reader might see an incorrect version of the data.

This is why isolation matters. The database must shield transactions from the side effects of others, to preserve the illusion that they each ran independently, even if they didn’t.

The ACID Properties

When we mention “correct” transactional behavior, it usually means adhering to ACID compliance.

ACID is a contract between the application and the database. It outlines four core guarantees that define what it means for a transaction to be trustworthy: Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability.

Each one addresses a different kind of failure or concurrency risk. Let’s look at them in a little more detail.

Atomicity

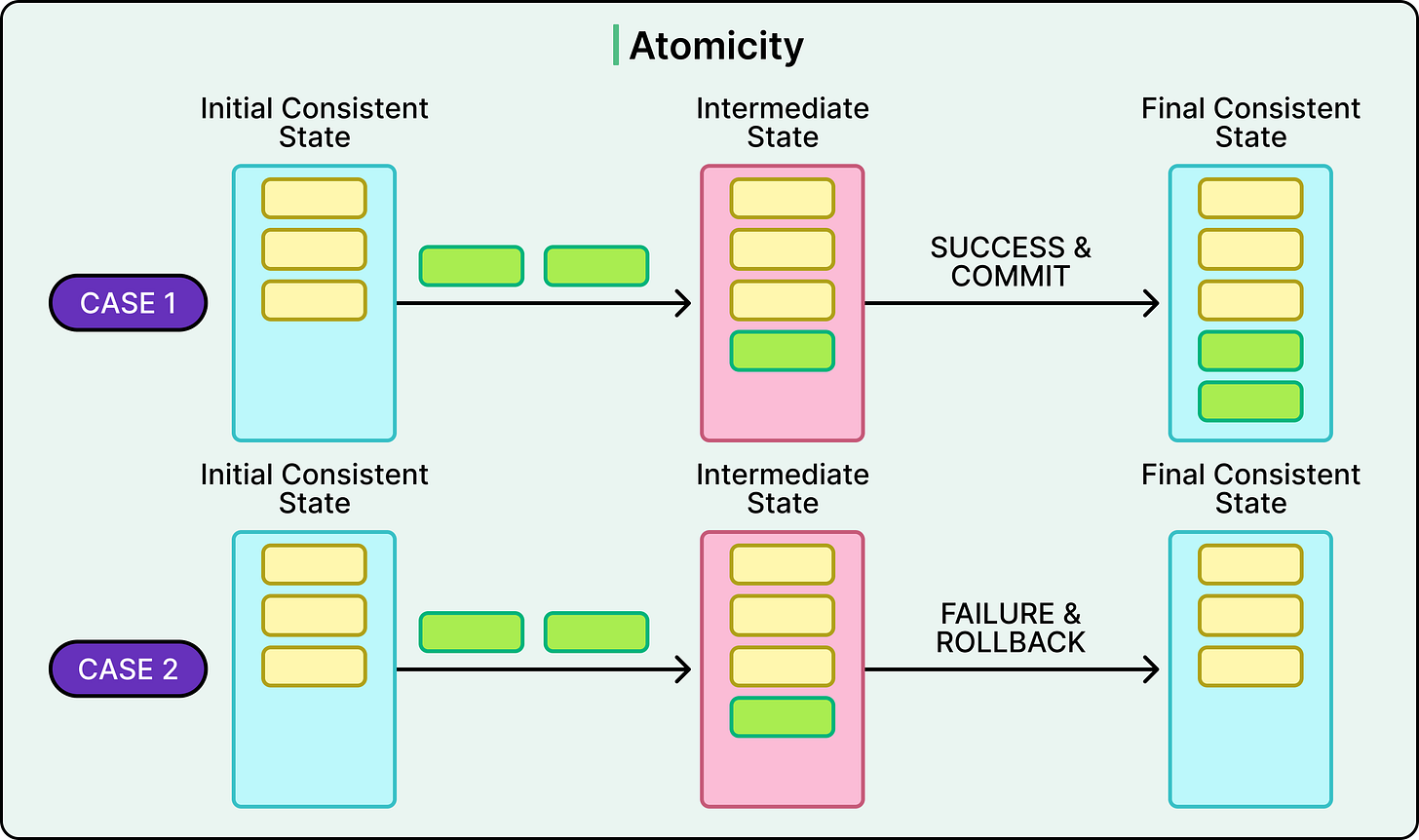

Atomicity ensures that every transaction either completes in full or has no effect at all. If a single step fails, the whole thing rolls back. There’s no room for half-success.

See the diagram below:

This is critical in multi-step operations.

Consider a transaction that deducts funds from one account and credits another. If the first step succeeds but the second fails, and there's no rollback, the money simply vanishes.

Atomicity prevents this class of data corruption.

Under the hood, atomicity is typically enforced using write-ahead logging (WAL) or undo/redo logs. Before applying any changes to the main storage, the database logs the intended operations. If the system crashes mid-transaction, it consults the log on restart: either roll everything back (undo log) or reapply changes that were pending commit (redo log).

This makes atomicity a foundational protection against system crashes, disk write failures, or application bugs that abort mid-flight.

Consistency

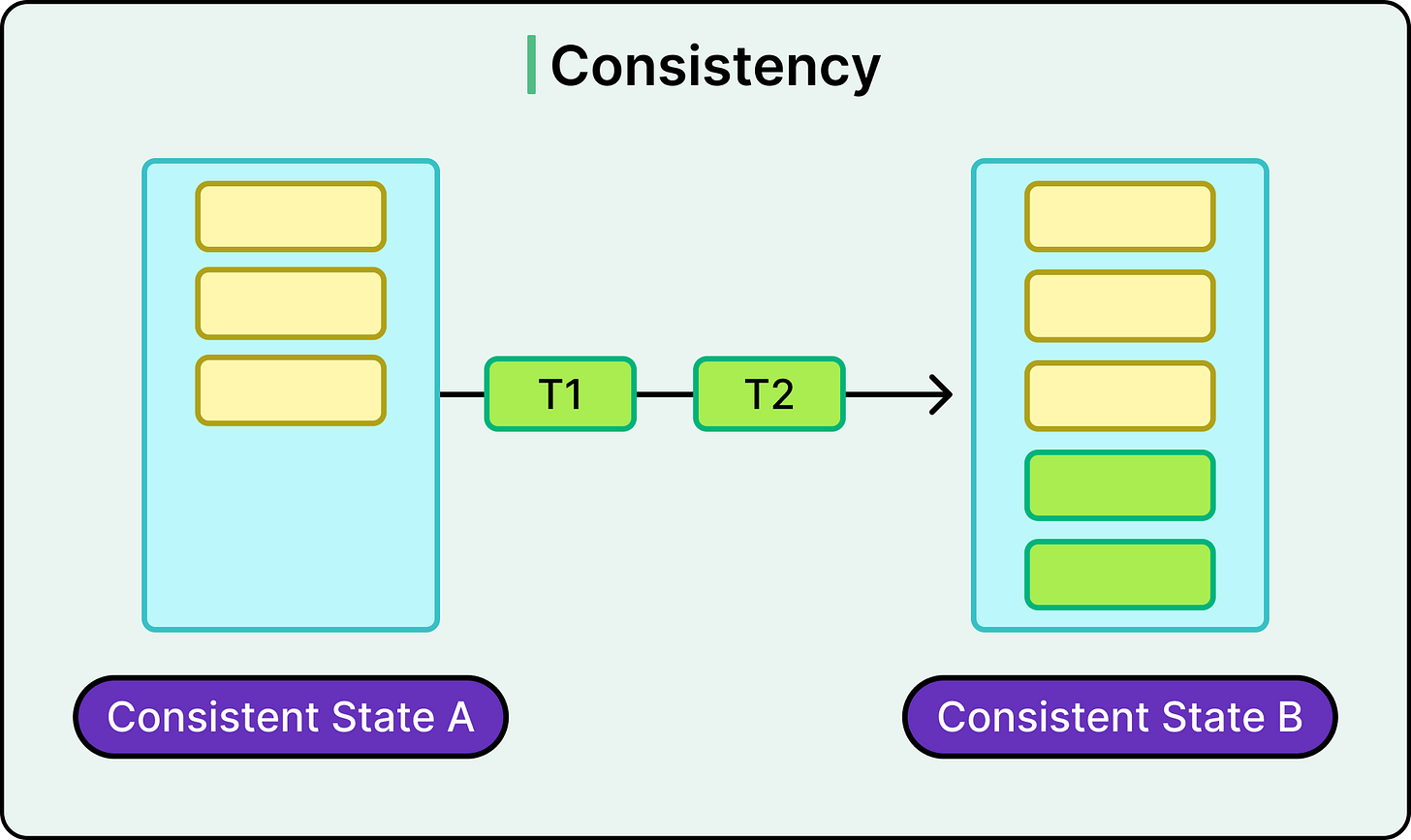

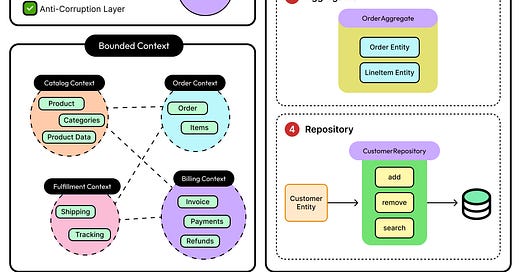

Consistency ensures that a transaction moves the database from one valid state to another.

A valid state is defined by constraints such as primary keys, foreign keys, data types, uniqueness, and any custom rules enforced by business logic.

Contrary to common belief, consistency isn’t fully enforced by the database. The system can guarantee internal constraints (for example, no duplicate keys), but application-level consistency (for example, “a driver can’t be assigned to two rides at once”) must be supported by the developer using logic or transaction scoping.

Still, the ACID contract guarantees that no transaction will leave the system in an invalid state from the database’s perspective. If a constraint is violated, the transaction fails and rolls back.

This results in predictable behavior even when many processes interact with the data at once.

Isolation

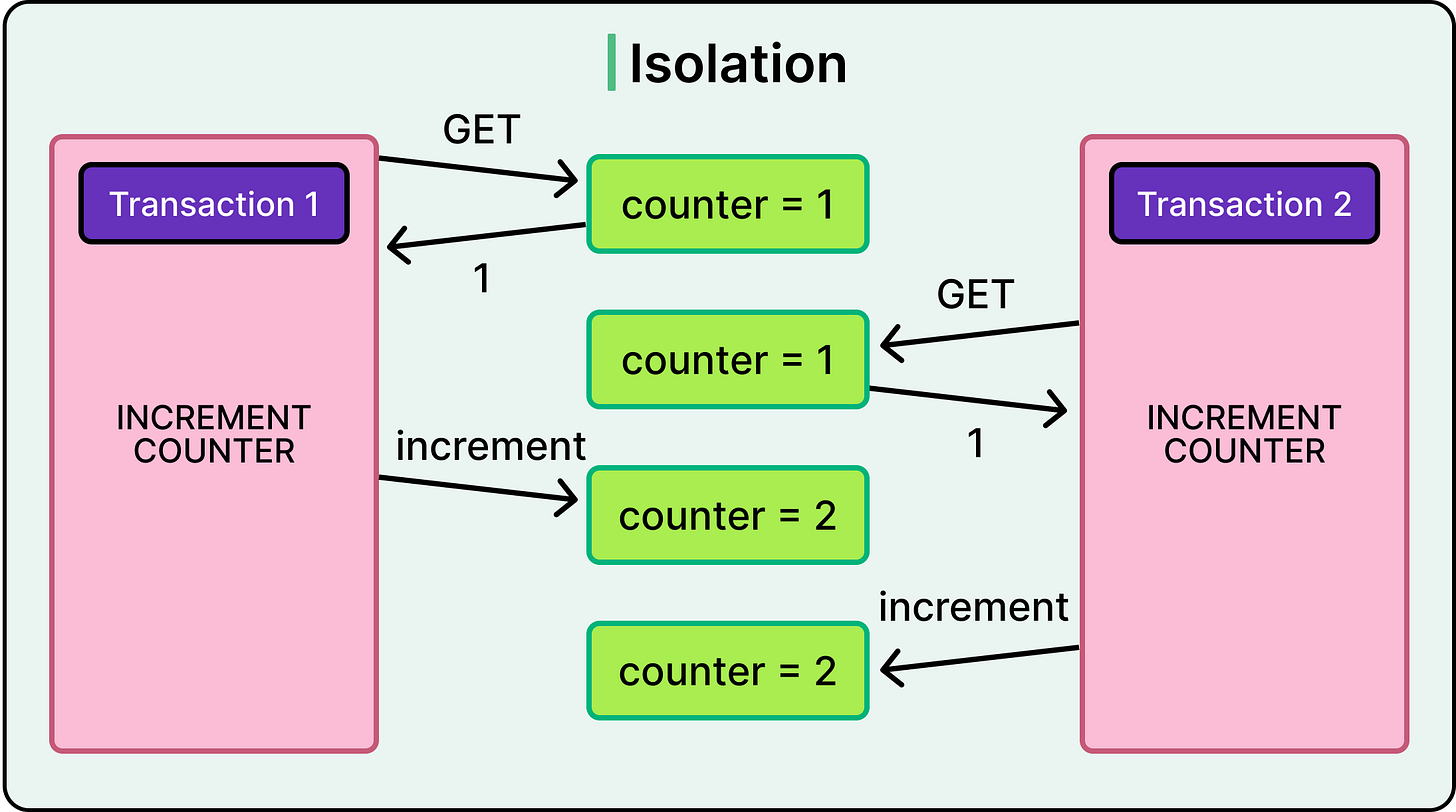

Isolation ensures that concurrently executing transactions do not see each other’s intermediate states. Each transaction must behave as if it were running alone, even though the database may be interleaving its operations for performance.

See the example below for reference:

Isolation is where things can get a little messy.

Full isolation (known as serializability) means transactions execute as if they were run in strict sequence. It’s safe but expensive. Most production systems run with weaker isolation levels to trade some safety for throughput.

There are generally four levels:

Read Uncommitted: It allows dirty reads where one transaction may see changes from another that rolls back later.

Read Committed: Only sees committed changes from other transactions. Prevents dirty reads but allows non-repeatable reads.

Repeatable Read: Guarantees that repeated reads within a transaction see the same data. Still allows phantom rows to appear on re-query.

Serializable: Enforces full isolation by making transactions behave as if they ran one after another. Rarely used outside of high-integrity systems.

These isolation levels aim to protect against common anomalies:

Dirty read: Reading uncommitted data from another transaction.

Non-repeatable read: Reading the same row twice and getting different results.

Phantom read: A new row appears in a subsequent read due to another transaction’s insert.

Each stronger level prevents more anomalies but increases contention and the risk of deadlocks. Choosing the right isolation level is a performance versus correctness decision. For example, financial systems may lean toward Serializable, while analytics dashboards might settle for Read Committed.

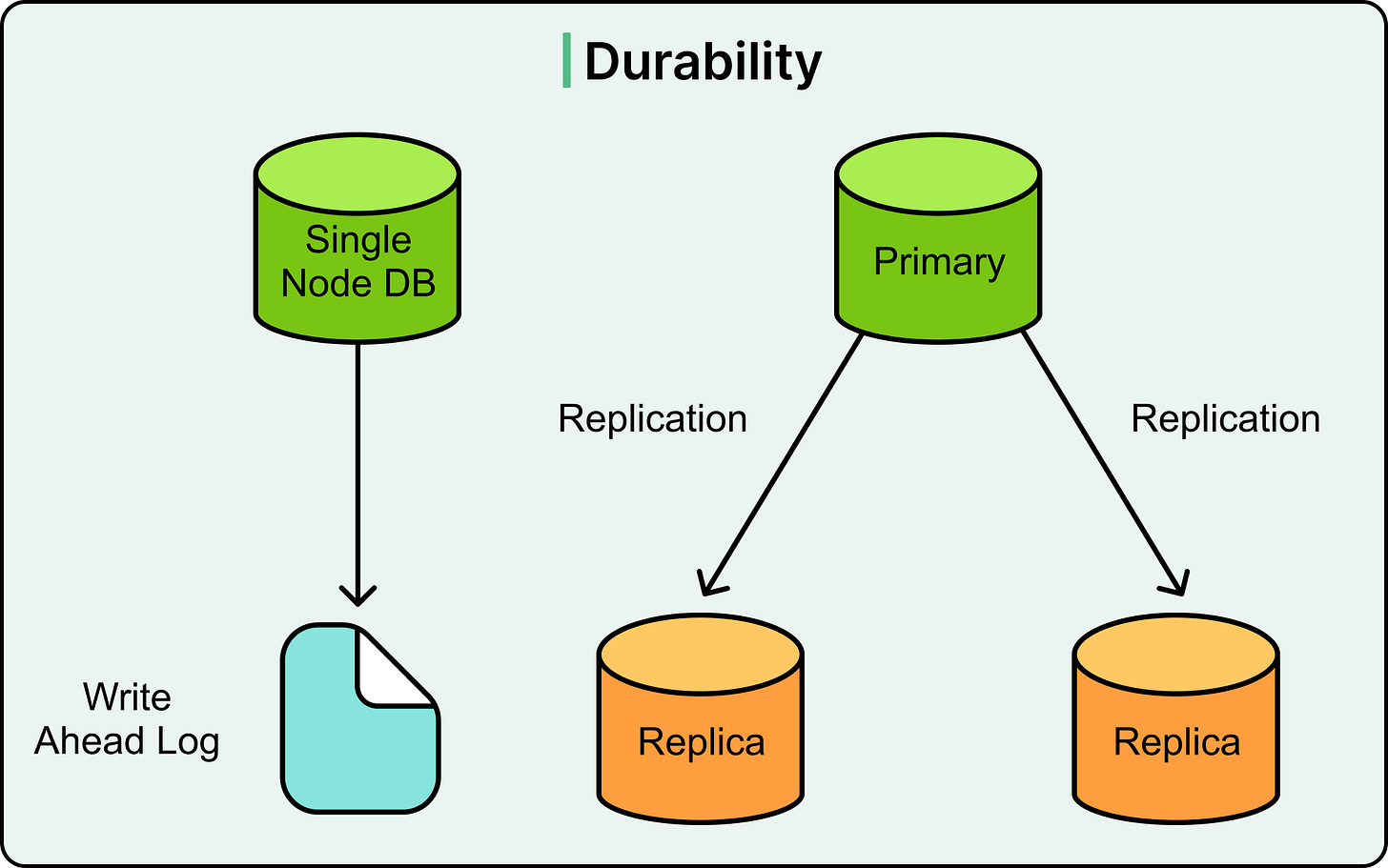

Durability

Durability ensures that once a transaction commits, its changes are permanent, even if the database crashes milliseconds later.

This guarantee exists because in distributed or stateful systems, crashes are inevitable. The durability property ensures that successful operations don’t vanish due to hardware failures, software crashes, or power loss.

Databases implement durability by persisting transaction logs (typically WAL files) to disk before acknowledging the commit. Other techniques for durability also include replication.

Concurrency Control

Databases don’t process one transaction at a time. As mentioned, it would waste resources and frustrate users.

Instead, they run transactions concurrently, allowing thousands of operations to execute in parallel. This improves throughput but creates a new class of problems: data races, dirty reads, lost updates, and consistency violations.

Imagine two users editing the same shopping cart at the same time, or two warehouse workers updating inventory for the same SKU. Without coordination, one update might overwrite the other. The system becomes unpredictable.

To preserve correctness in the presence of concurrency, databases rely on concurrency control mechanisms. These techniques ensure that even when transactions overlap, the final result is consistent and logically sound, as if the transactions had been executed in some serial order.

There are two main strategies to achieve this: pessimistic locking and optimistic locking. Let’s look at both in more detail:

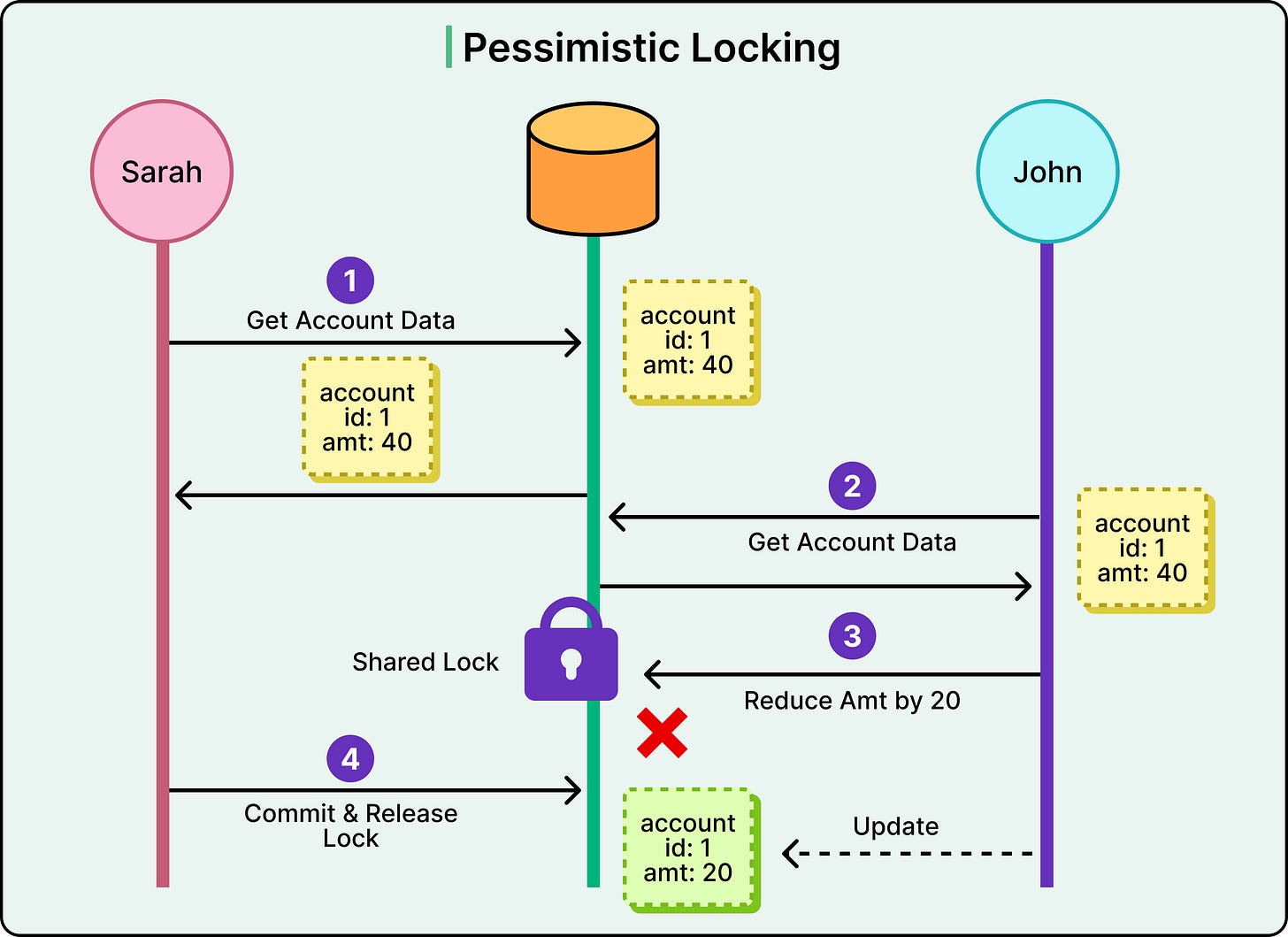

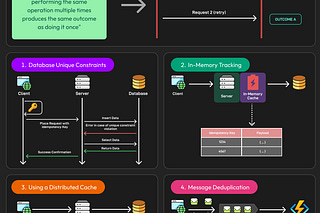

Pessimistic Locking

Pessimistic locking assumes that conflicts are likely. It protects data by locking it upfront before other transactions get a chance to touch it.

The idea is simple: if one transaction wants to read or write a piece of data, it grabs a lock, and everyone else waits for their turn.

This model avoids surprises. There’s no need to roll back later because a conflict is blocked from happening in the first place. But that safety comes at a cost. Blocking can become a bottleneck under heavy load.

Pessimistic locks can be applied at different granularities:

Row-level locking: The most precise form of locking. Only the rows being read or written are locked.

Table-level locking: This is coarser. The entire table is locked, preventing others from modifying any row.

Page-level locking: Locks a group of rows stored together on disk. Rare in modern OLTP systems but still used in some engines.

Here’s an example flow of pessimistic locking:

Sarah requests account data from the database for account ID 1. The current balance is 40.

The database responds with the data and places a shared (read) lock on the row. No other transaction can write to it until this lock is released.

John tries to read the same account. Because the row is locked, he must wait. His read is blocked until Sarah’s transaction is finished.

Sarah reduces the balance by 20, updating the account to 20.

She commits the transaction, and the database releases the lock.

Only now can John proceed, but by then the balance has changed. If he re-reads the row, he sees the updated value.

See the diagram below for a high-level reference to pessimistic locking.

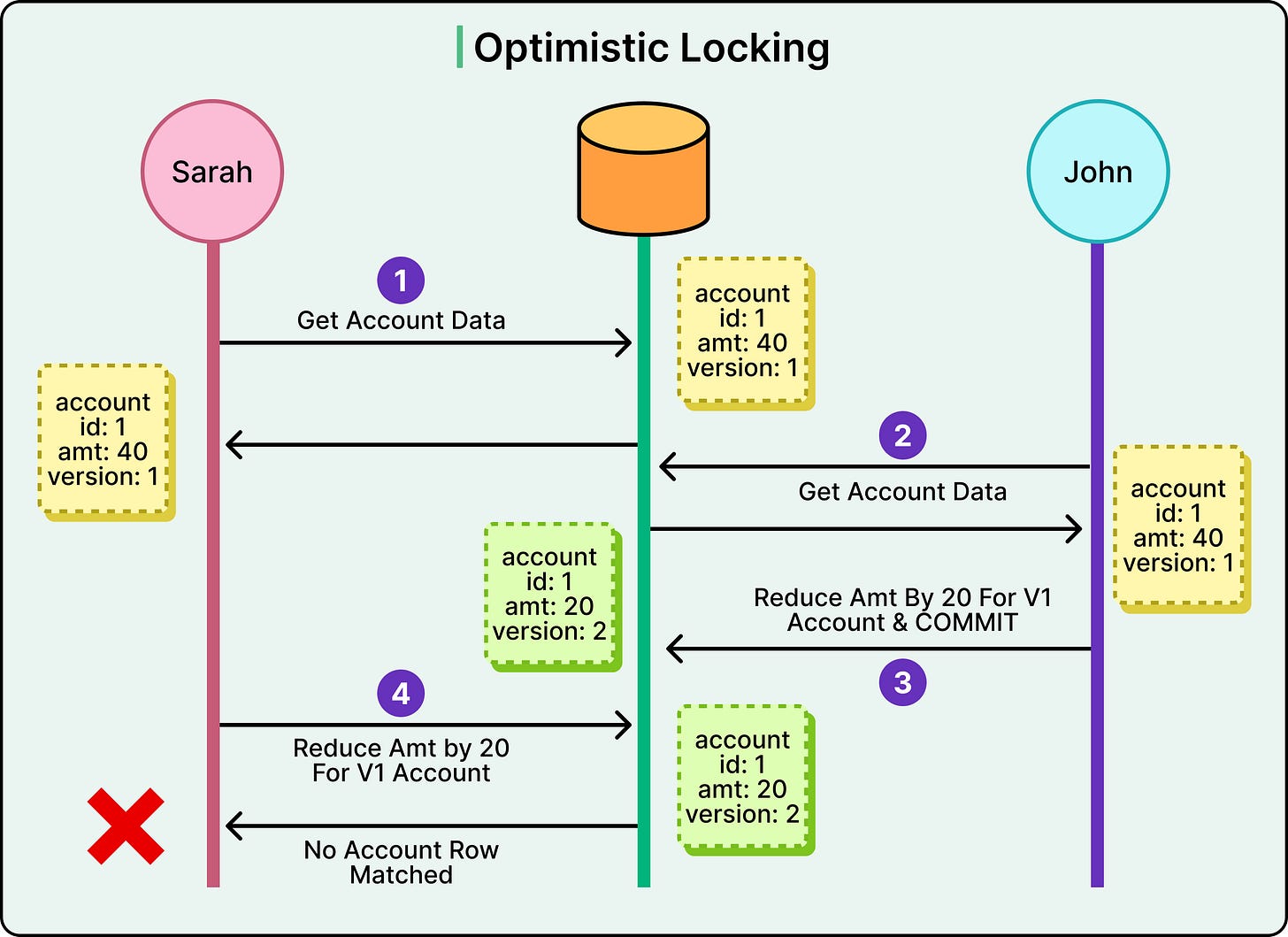

Optimistic Locking

Optimistic locking allows transactions to proceed without locking anything upfront. Validation happens at the end. If a conflict is detected, the transaction rolls back.

This model reduces blocking and improves throughput in read-heavy systems with low contention. It’s ideal for workloads like user profile updates, document editing, or background processes that touch different parts of the dataset.

A typical sample optimistic locking flow looks like this:

Sarah reads the account data, which includes both the balance and a version number (version: 1).

John also reads the same data with the same version number (version: 1). No locks are placed at this stage. Both transactions proceed.

John attempts to reduce the balance by 20 and commit his change. At commit time, the database checks: is the row still at “version: 1”?

If this is the case, the update succeeds and the version is incremented to 2.

Sarah then tries to commit her update, also expecting the row to still be at “version: 1”.

But the version has changed to 2, so the database rejects the update. No row matches the original versioned condition.

Sarah’s transaction fails, and she must retry with the latest data.

See the diagram below for reference:

Many systems implement this pattern using a version column or last-modified timestamp. At commit time, they run a conditional update. Here’s a simple example:

UPDATE products

SET stock = 150, version = version + 1

WHERE id = 42 AND version = 3;Optimistic locking tries to avoid deadlocks wherever possible. However, that doesn’t mean it’s always better.

This approach can run into problems during high-contention scenarios. If many transactions try to update the same record, most of them will fail and retry, creating a thundering herd. Systems that can’t tolerate high retry rates can struggle.

Best Practices

Transactional semantics show up every time a backend service touches shared state, whether it’s booking a ticket, updating inventory, or deducting credits from a user's wallet.

Here are some best practices that should be kept in mind:

Keep transactions short and focused: The longer a transaction holds locks or occupies resources, the higher the risk of contention, blocking, or deadlocks. Avoid doing network calls, user prompts, or complex calculations inside an open transaction. Read what’s needed, write what’s necessary, and commit quickly.

Access data in a consistent order: Many deadlocks arise from transactions acquiring locks in different sequences. By standardizing access order, we can reduce the risk significantly.

Choose isolation levels deliberately: Don’t default to Serializable just because it sounds safe. In many use cases, Read Committed or Repeatable Read provides sufficient guarantees with better performance.

Know your database’s concurrency model: Different databases behave differently. PostgreSQL uses MVCC and snapshot isolation. MySQL’s InnoDB engine applies a mix of row-level locks and MVCC, but handles repeatable reads differently. SQL Server enforces locks more aggressively unless snapshot isolation is enabled. Understanding how your chosen system implements locking, isolation, and deadlock detection is essential tuning knowledge.

Build retry logic that’s resilient: Transaction retries should back off, log intelligently, and respect context timeouts.

Summary

We have looked at database transactions and concurrency control strategies in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Transactions ensure that a group of operations either all succeed or none do, maintaining consistency in the face of failures or concurrency.

A solid grasp of transactional behavior and concurrency control is essential for building safe, high-integrity backend systems.

The ACID properties (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability) define the fundamental guarantees of reliable transactional systems.

Atomicity and Durability are enforced through mechanisms like write-ahead logs, ensuring no partial changes and recovery after crashes.

Consistency depends not just on the database but also on application-level rules and constraints.

Isolation protects transactions from interfering with one another, with different levels (Read Committed to Serializable) offering trade-offs between safety and performance.

Concurrency control prevents race conditions and inconsistencies, using pessimistic or optimistic techniques depending on workload characteristics.

Pessimistic locking uses explicit locks to prevent conflicts, while optimistic locking avoids them by validating data versions at commit time.

Engineering best practices include keeping transactions short, accessing data in a consistent order, tuning isolation levels deliberately, and implementing proper retry logic.

see description and pictorial of pessimistic , in picture

Sarah reduces the balance by 20, updating the account to 20.

in actual john is reducing it

may I know why you write half baked knowledge in paid articles?

so you mentioned we have isolation level as serializable , then why do we need locking?

pictorial diagram of optimistic locking and pessimistic locking is almost same?

CAN YOu explain trade offs?