When query performance degrades, most engineers tend to reach for the application code first to identify issues.

However, the root cause can also reside closer to the data at the storage level, and indexing could be the difference between a targeted lookup and a blind table scan that negatively impacts performance. With the right index in place, a query that once sifted through millions of rows can return results in milliseconds.

As datasets grow, the cost of scanning becomes untenable. Databases store data in pages, rows, and blocks, which are not optimized for arbitrary reads. Without indexes, every query that filters or sorts must inspect more rows than necessary. Multiply that overhead by thousands of queries per second, and systems start to buckle under I/O pressure.

Indexing solves this by narrowing the search space. Instead of traversing the entire table, the database engine uses a precomputed structure to jump closer to the target, much like flipping straight to the index of a book instead of reading every page.

But not all index types behave the same way. Some are built for fast key lookups. Others optimize range scans. Some improve performance for specific queries while adding overhead elsewhere.

In this article, we will explore the basic concept of database indexing and different index types. We will also understand what each index type does, when it helps, and what it costs.

What is a Database Index?

A database index is a structure that maps column values to the physical locations of rows in a table. Its purpose is to speed up data access. Instead of scanning every row to find matching values, the database engine consults the index to jump directly to the relevant rows.

Imagine a table containing millions of customer records and the following query.

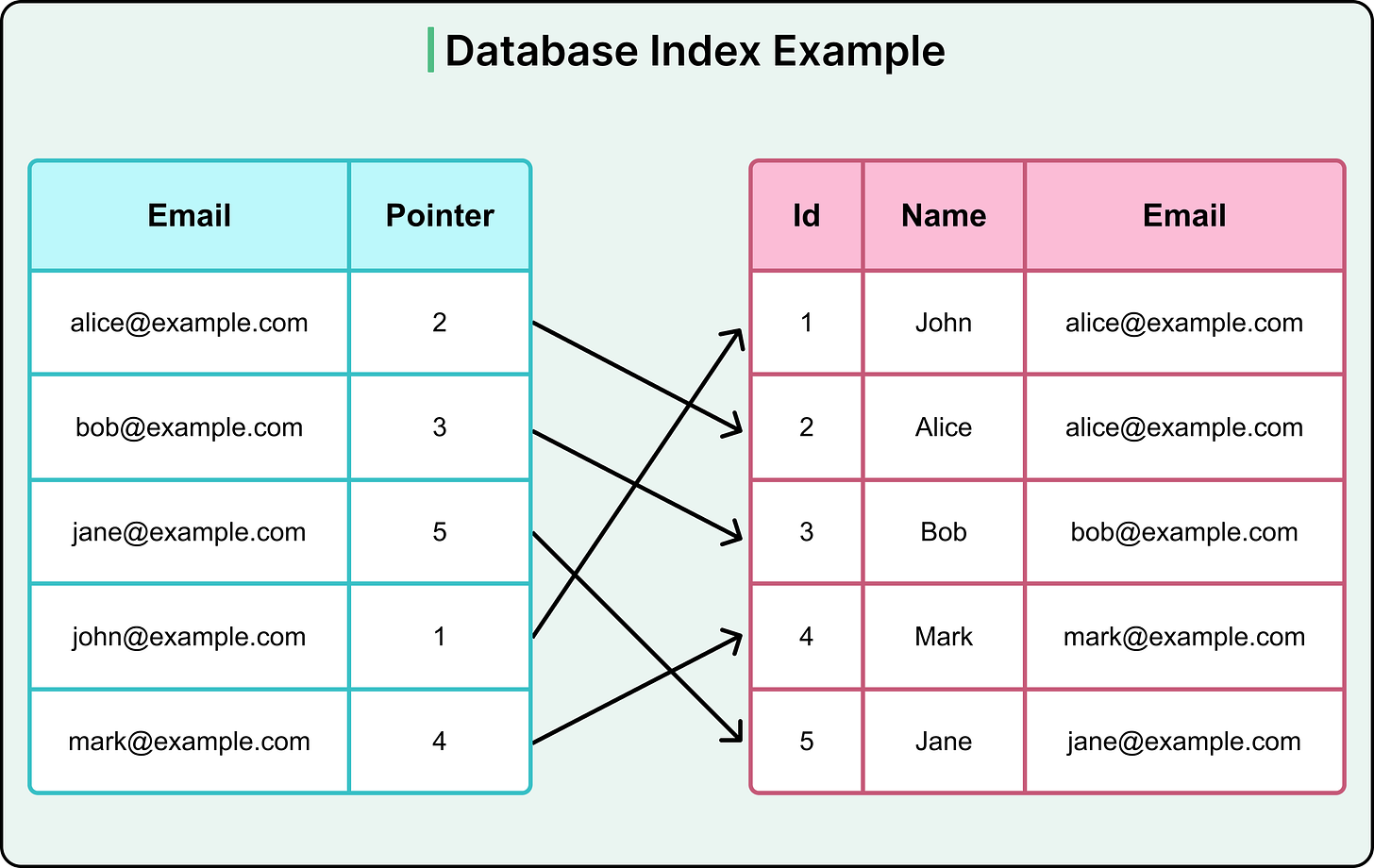

SELECT * FROM customers WHERE email = alice@example.com';Without an index, a query like this forces the engine to examine every row in the customers table. That’s a full table scan, which is costly, slow, and unnecessary when looking for a single record.

With an index on the email column, the database consults a compact lookup structure. It finds the entry for the email address, follows a pointer, and retrieves the row directly.

Indexes are built on one or more columns. They can be defined on a single field, such as email, or a combination like (last_name, first_name) for composite lookups. They work best when aligned with the filtering, joining, or sorting patterns of your queries.

However, indexes are not free. They consume storage and must be maintained during inserts, updates, and deletes. Every additional index adds cost to write-heavy operations. This is why indexing is not a 'more is better' game. It’s important to choose the right index that reflects how data is accessed.

How Does an Index Work?

As mentioned, an index works by reducing how much of the table the database needs to read for a query. Instead of scanning every row to check whether it matches a filter, the database engine uses the index to jump straight to a shortlist of candidates.

Let’s walk through how an index gets used during query execution.

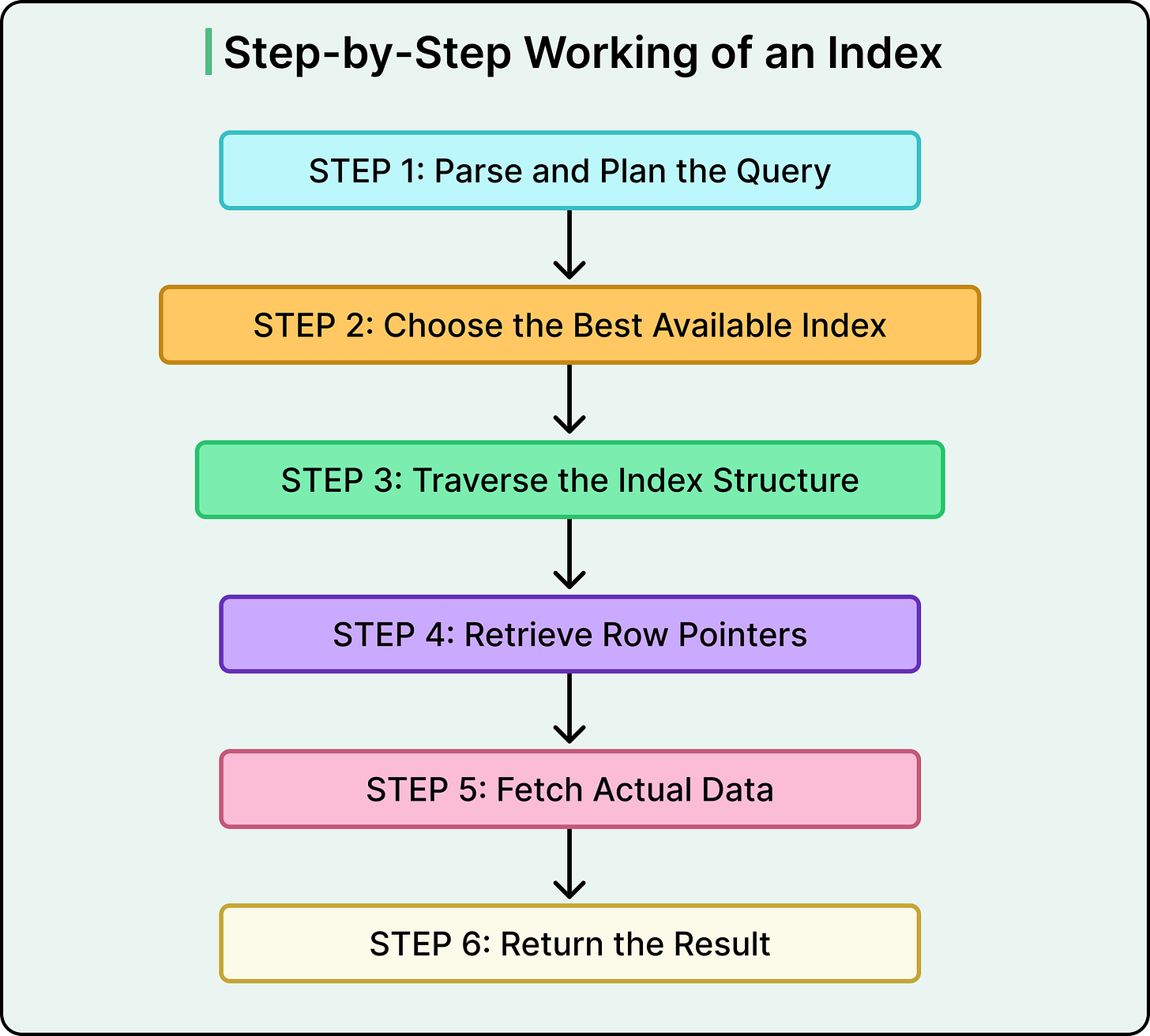

Step 1: Parse and plan the query. The database engine parses the SQL and begins constructing an execution plan. It checks what indexes are available on the columns used in filters, joins, and sorting.

Step 2: Choose the best available index. If a suitable index exists (say, on customer_id), the query planner decides whether to use it. This depends on the expected number of matching rows and the cost of the index versus table scan. If the planner estimates that the index will reduce I/O, it chooses it.

Step 3: Traverse the index structure. Most general-purpose indexes are implemented as B-trees. The engine traverses this tree from the root, down through branches, and finally to the leaf node containing the matching customer_id. Each level narrows the search space, like using alphabetical tabs in a dictionary.

Step 4: Retrieve row pointers. Once the matching entry is found, the index provides either a direct pointer to the physical row (in the case of a clustered index) or a reference to the primary key or row ID (for a non-clustered index).

Step 5: Fetch the actual data. If the index includes all the needed columns, the engine can return results without touching the table. Otherwise, it uses the pointer to retrieve the full row from disk or memory.

Step 6: Return the result. With the row(s) in hand, the engine assembles the final result set and returns it to the application.

This process allows the database to narrow down millions of rows to a handful of candidates in milliseconds. And while the developer typically doesn’t control whether the index is a B-Tree or a Hash, they do control what columns are indexed, in what combinations, and for which access patterns. That’s where the design work happens.

Core Index Types: Based on Structure

Indexes can play different roles depending on how they relate to the table's structure and data layout.

The most foundational distinction lies in whether an index determines how the table’s data is physically stored (clustered) or simply provides an auxiliary access path (non-clustered).

Let’s break down these three core types.

1 - Primary Index

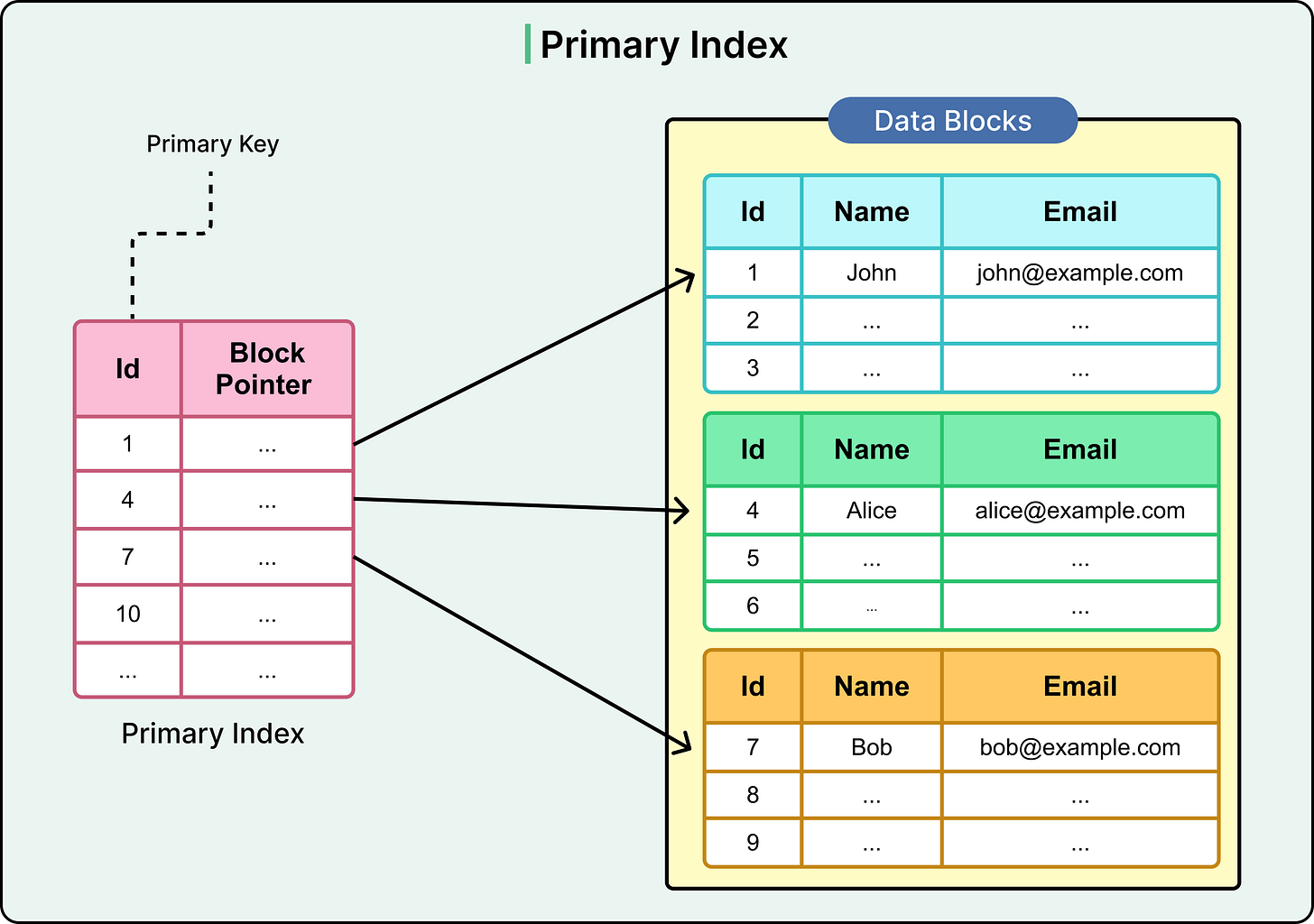

A primary index is automatically created when a primary key is defined on a table. It guarantees that each value in the indexed column (or column set) is unique and not null.

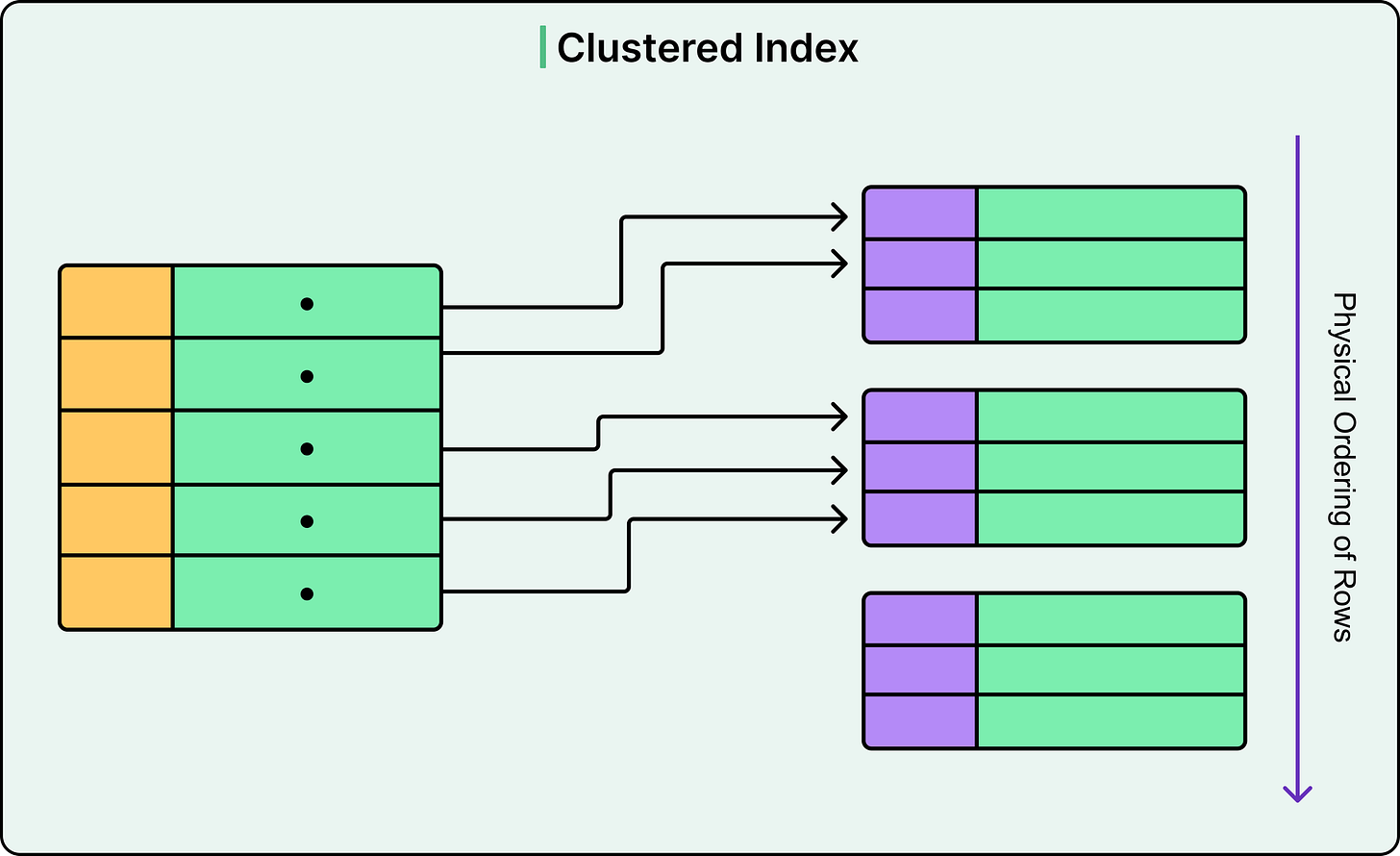

See the diagram below to understand the concept of a primary index.

In many databases, such as MySQL's InnoDB, the primary index also becomes the clustered index. This means the table’s rows are physically ordered on disk by this key.

For example, consider the following table of customer records:

CREATE TABLE customers (

customer_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100),

email VARCHAR(100)

);Here, the customer_id column serves as the primary index. Now, consider the following query:

SELECT * FROM customers WHERE customer_id = 501;This query can use this index to jump directly to the corresponding row without scanning any others. Since the index is clustered in InnoDB, the row lives exactly where the index says it does.

The key traits of a primary index are as follows:

It enforces uniqueness.

Backed by physical ordering in some engines.

Often used as the base reference for other indexes.

2 - Clustered Index

A clustered index determines the physical order of rows in a table. Only one clustered index can exist because data can only be stored in one order at a time. This layout benefits range queries, ordered scans, and I/O efficiency, since related rows live close together on disk.

For example, consider an orders table with an auto-incrementing order ID:

CREATE TABLE orders (

order_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

customer_id INT,

order_date DATE

);Here, the order_id serves as the clustered index. Now, consider the following range query:

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE order_id BETWEEN 1000 AND 1100;This performs well because the rows are stored sequentially. Some engines, like SQL Server, allow developers to define which index is clustered explicitly, even if it's not the primary key.

Some key traits of a clustered index are as follows:

Defines physical row order

Optimizes range and ordered queries

Only one allowed per table

Acts as the lookup base for non-clustered indexes

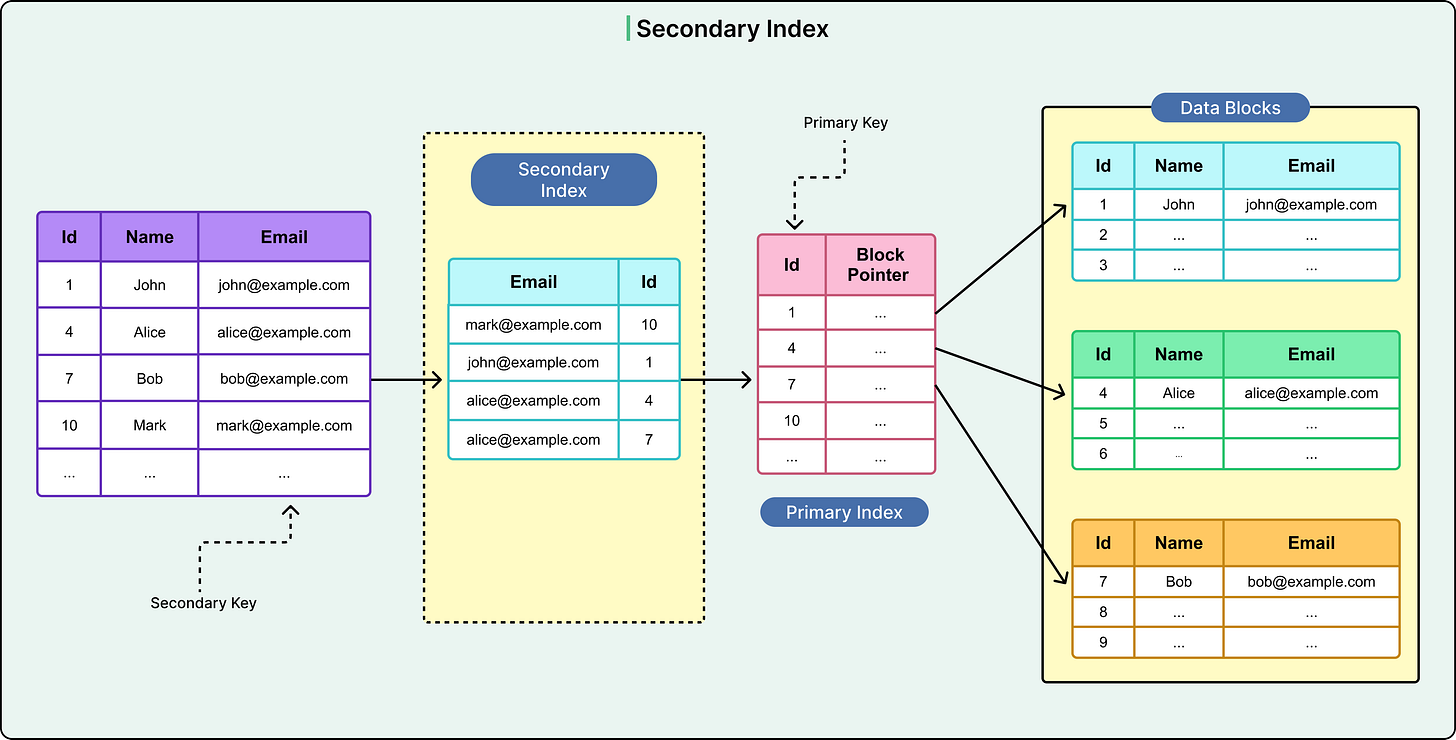

3 - Non-Clustered (Secondary) Index

A non-clustered index is a separate structure that holds a copy of one or more columns along with pointers to the actual rows in the table. It does not affect how data is physically stored. Non-clustered indexes are used to optimize filters, joins, or aggregations on columns other than the primary key.

See the diagram below:

For example, suppose there’s a need to frequently query orders by a customer’s email address:

CREATE INDEX idx_email_id ON orders(email);Now, consider the following query

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE email = “john@example.com”;The index removes the need to scan the entire table. The engine uses idx_email_id to find all matching row pointers, then fetches each row using the clustered index.

However, this two-step process can add I/O cost, especially in scenarios when many rows match and the index is not a covering index.

The key traits of a secondary index are as follows:

Doesn’t define physical order.

Can be many per table.

Useful for filtering and joins.

Requires extra reads to fetch full rows unless covering the query.

Index Types: Based on Data Coverage

Not all indexes need to represent every row in the table. Some track every single key value. Others take a lighter approach, indexing only a portion of the data and relying on proximity or block-level layout to resolve the rest.

These design choices shape how precise an index is, how much storage it consumes, and how fast it can respond under pressure.

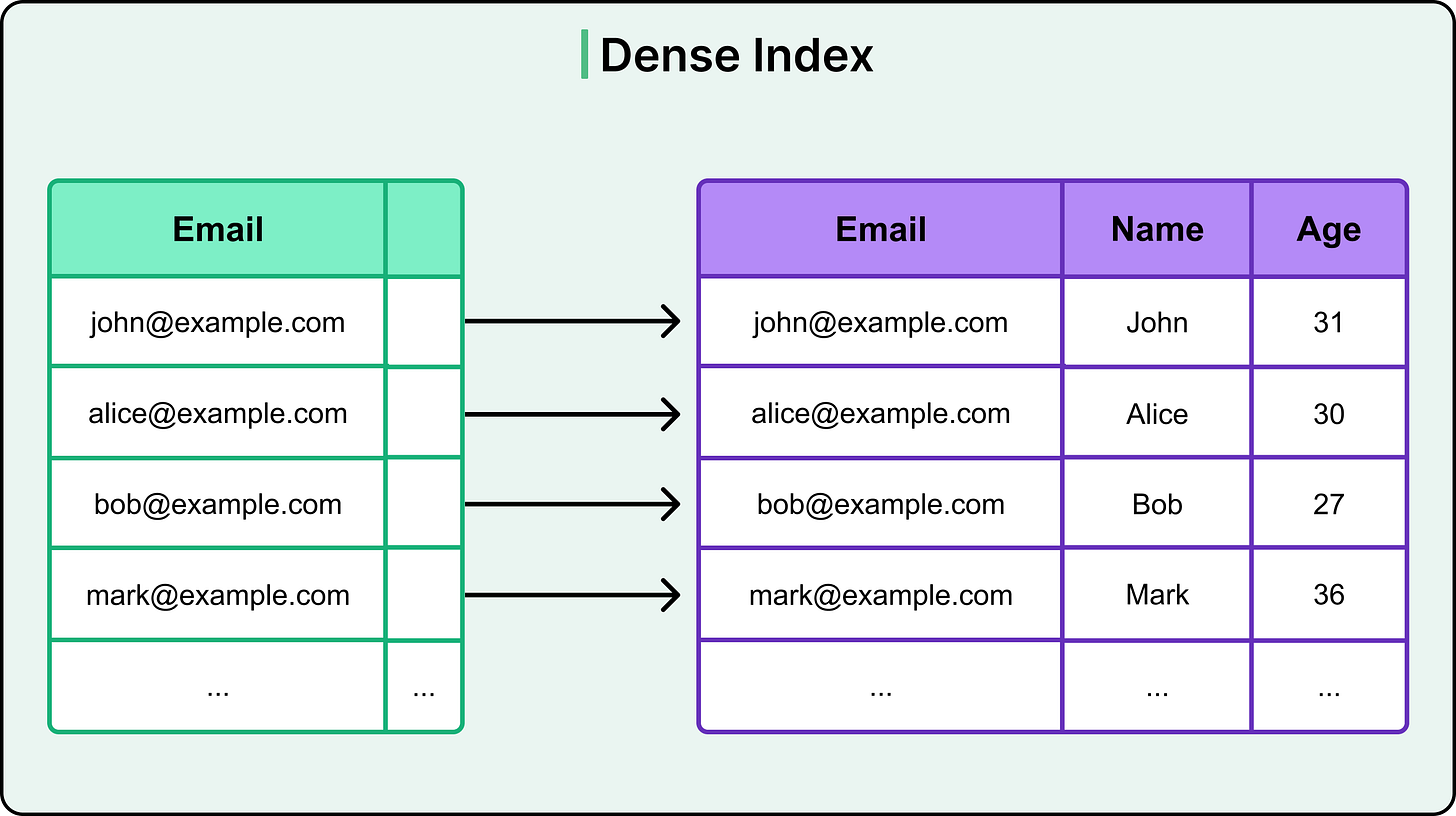

1 - Dense Index

A dense index contains one entry for every row in the table.

For each unique key value, the index holds a direct pointer to the exact location of that row. This provides high precision and consistent performance, especially when every record needs to be reachable through the index.

See the diagram below:

Dense indexes are ideal in read-heavy systems where fine-grained lookups are frequent. For example, consider a users table with a dense index on email:

CREATE INDEX idx_email ON users(email);Every email address in the table appears in the index. Now, consider the following query searching for a specific email:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE email = 'sam@demo.com';This query uses the index to find the row directly. Since every row has an entry, the engine doesn’t need to search or scan beyond the index. The access path is predictable and fast.

The use cases of dense index are as follows:

Equality lookups in transactional systems.

Tables where every row is queried independently.

Situations requiring consistent lookup times.

However, there are also trade-offs such as:

Higher index size.

Slower insert and update performance due to maintenance overhead.

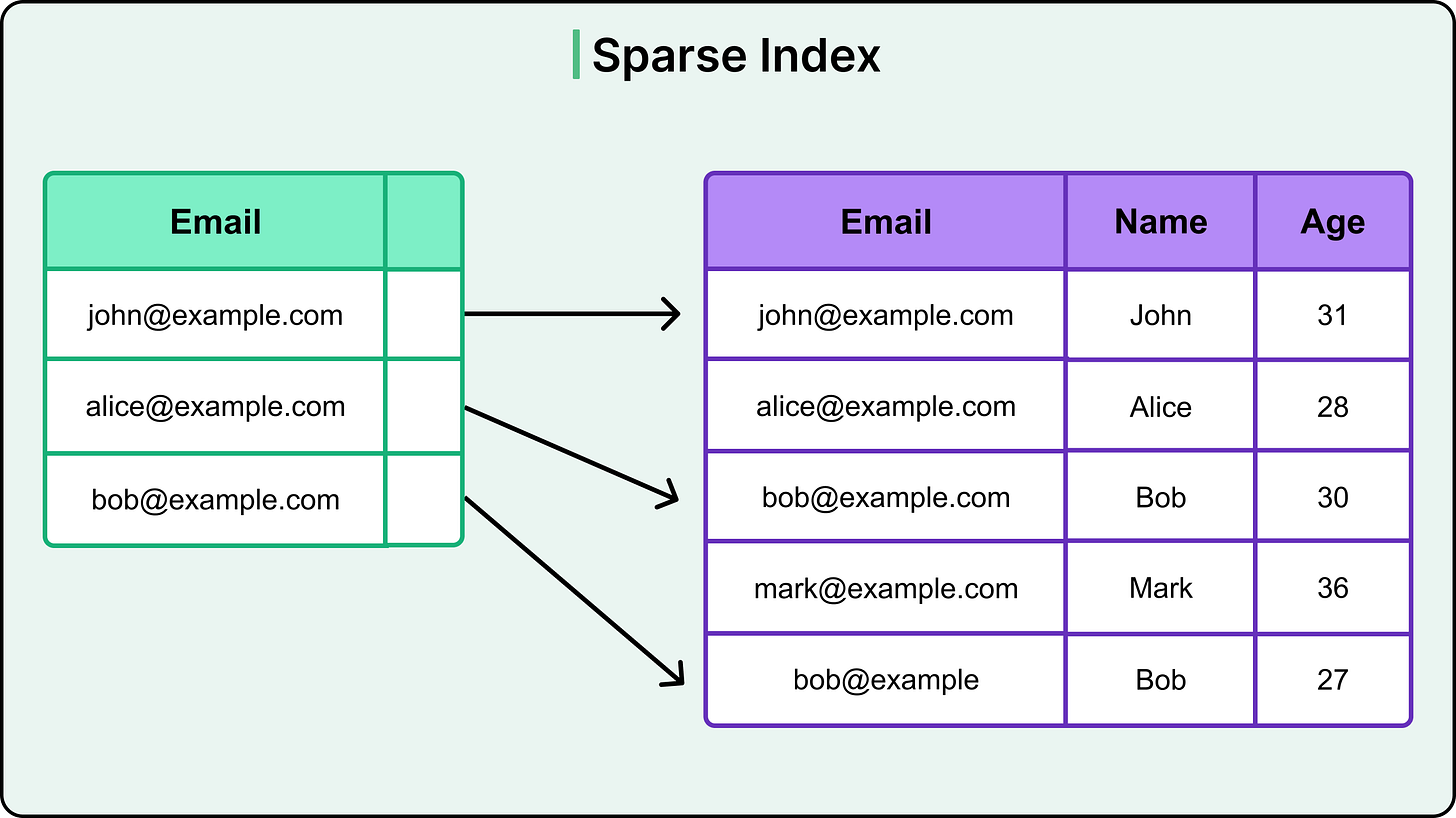

2 - Sparse Index

A sparse index contains entries for only some rows in the table. Typically, it includes the first row of each block or page of data. When a query matches a value not directly represented in the index, the engine locates the closest indexed key and scans forward until it finds the target row.

See the diagram below:

Sparse indexes reduce index size and maintenance cost but rely on table organization to keep the scan distance minimal.

For example, consider a read-optimized table sorted by order_date. A sparse index might include only one entry per date block. Consider the following query:

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE order_date = '2024-12-01';This query can use the sparse index to jump to the beginning of that date range, then scan within the block to find the exact match. This works well when rows are stored in order and access patterns align with the index granularity.

Common use cases of sparse index include:

Analytical queries over sorted datasets.

Data warehouses with bulk loads and infrequent updates.

Range queries where full precision isn’t needed.

The trade-offs are as follows:

Lower index size and write cost.

Lookup precision depends on data layout.

May require additional scanning after index access.

Logical Index Types

Beyond primary and structural indexing, modern databases offer specialized index types designed to match specific query behaviors.

These logical indexes don’t change how data is physically stored but instead help optimize for patterns that don’t fit neatly into traditional key lookups.

Let’s look at them in more detail.

1 - Filtered Index

A filtered index contains entries only for rows that match a defined condition. This makes it lighter and more targeted than a full index on the same column. It's especially useful when most queries focus on a subset of the data.

For example, consider a users table where only active users are queried frequently. We can create an index as follows in SQL Server. Also, PostgreSQL supports the same feature, but it is known as “partial index”.

CREATE INDEX idx_active_users ON users(last_login)

WHERE status = 'ACTIVE';Now, consider the following query.

SELECT last_login FROM users WHERE status = 'ACTIVE';This query can use the filtered/partial index to return results quickly without scanning inactive users. This not only speeds up reads but also reduces index size and maintenance cost.

Some common use cases for the filtered index are as follows:

Tables with archived or infrequently accessed rows.

Queries that filter on a Boolean or status column.

Large datasets where partial indexing improves cache efficiency.

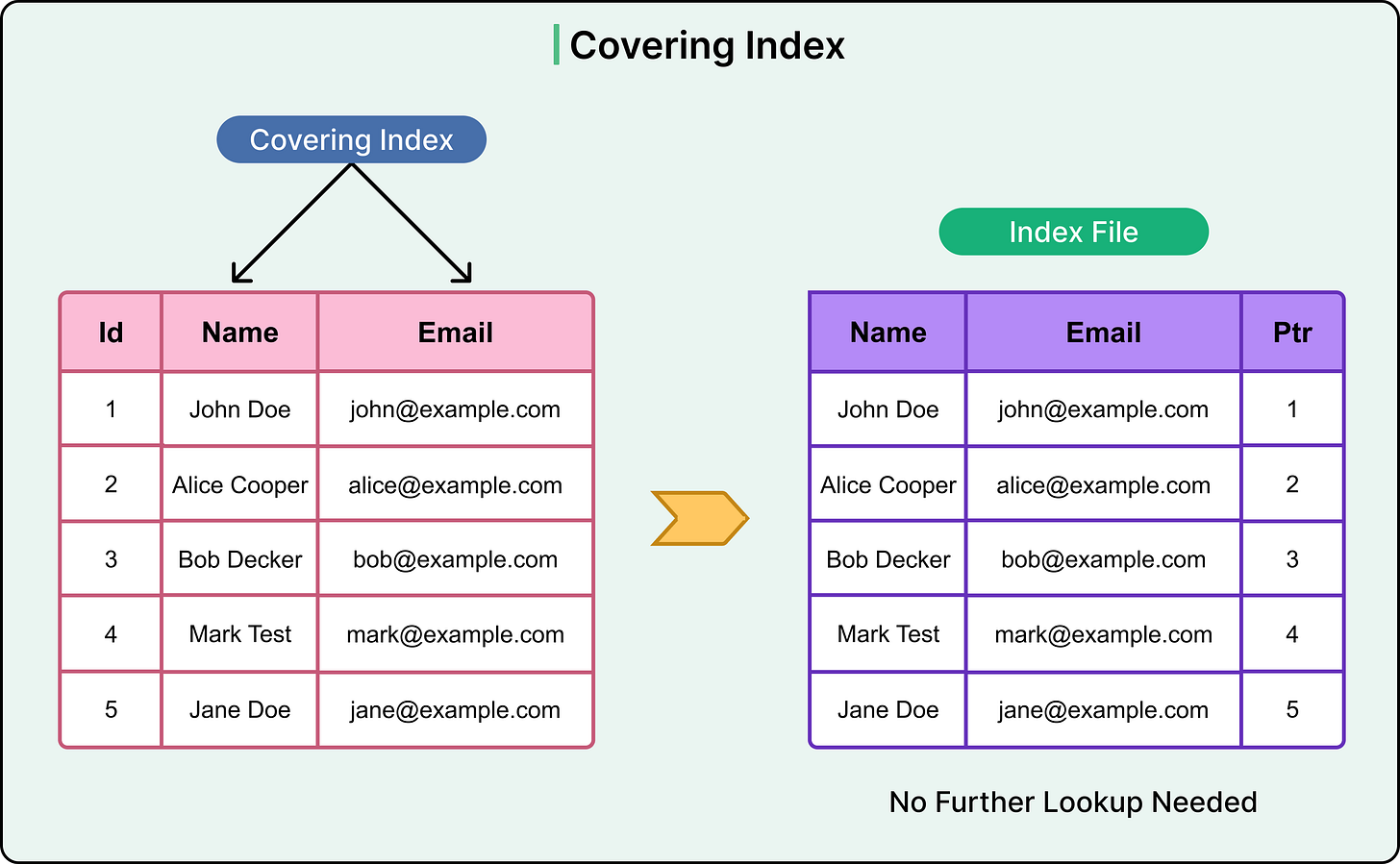

2 - Covering Index

A covering index includes all the columns a query needs. This includes those used in filters, joins, and the SELECT clause. Because all required data is already in the index, the engine doesn't need to touch the base table. This saves disk I/O and improves response time.

See the following example:

For example, consider that we want to find the email address of a user named “Bob Decker”.

SELECT Email FROM users WHERE Name = 'Bob Decker';In this case, the WHERE clause filters by Name and the SELECT clause retrieves Email. Both columns are contained in the covering index. See the following query that creates a covering index. The syntax can vary from database to database, but the high-level idea remains the same.

CREATE INDEX idx_name_email ON users(Name, Email);This allows the query to be fully resolved from the index itself.

Here are the use cases of a covering index

Read-heavy systems with stable query patterns.

Frequently accessed reports or dashboards.

Performance-critical endpoints where latency matters.

3 - Function-Based Index

A function-based index applies a transformation or expression to a column before indexing it. This allows queries that filter on computed values to still benefit from an index.

For example, if searches frequently normalize email addresses to lowercase, as per the following query.

SELECT * FROM users WHERE LOWER(email) = 'ana@example.com';In this case, a traditional index on email won't help. Instead, a functional index can be defined as follows:

CREATE INDEX idx_lower_email ON users(LOWER(email));Now, the query can leverage the index directly, since the transformation matches what's stored in the index.

The use cases are as follows:

Case-insensitive or trimmed string comparisons.

Date extraction (for example, indexing DATE(timestamp)).

Custom business logic that is applied during filtering.

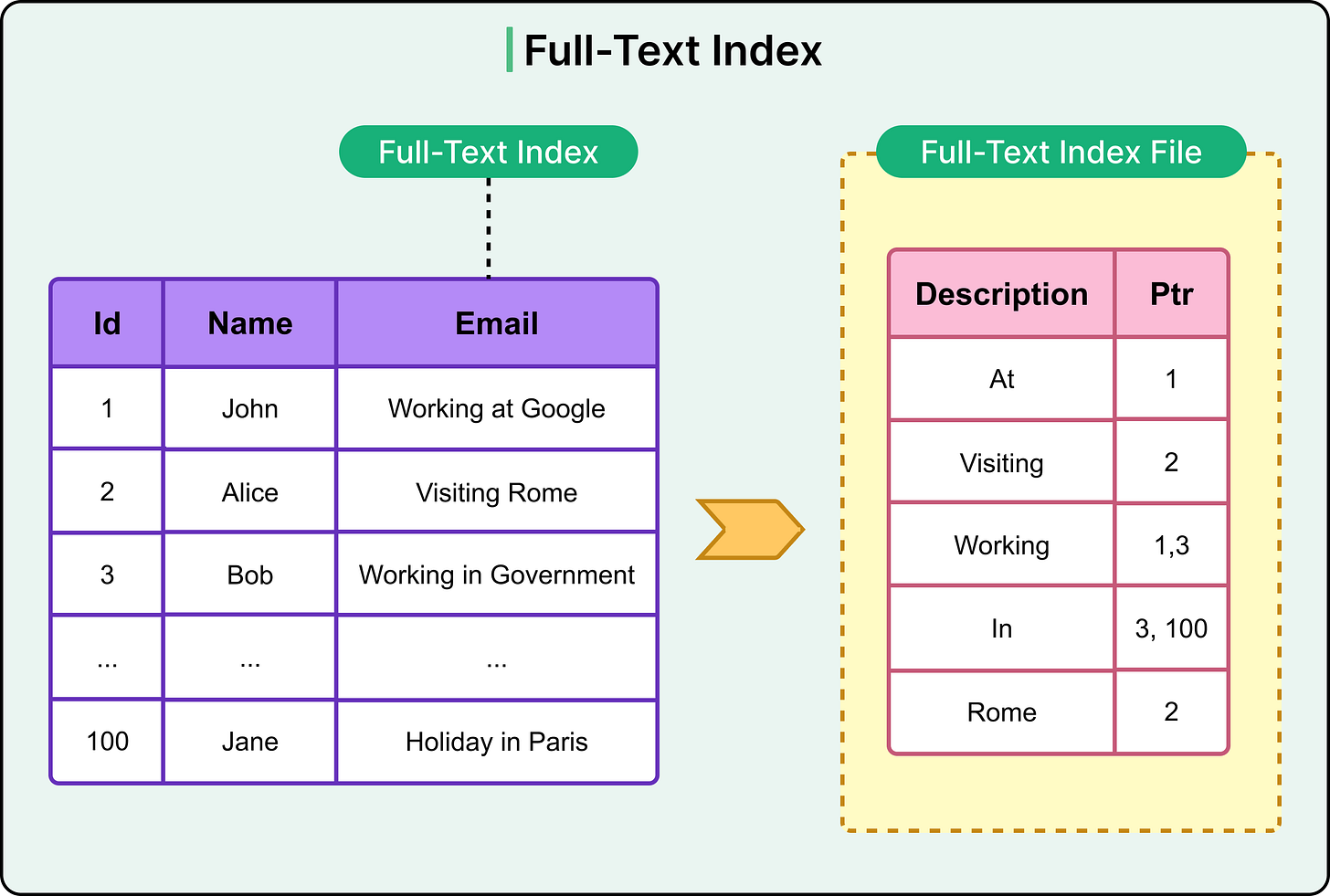

4 - Full-Text Index

A full-text index supports search over large text fields like product descriptions, blog posts, or comments. It breaks content into terms and creates an inverted index mapping terms to rows. This enables fast keyword, phrase, or relevance-based search.

See the diagram below:

The use cases are as follows:

Search bars on e-commerce or content platforms.

Document indexing and retrieval.

Applications requiring fuzzy or partial matching.

Summary

We’ve now looked at the key principles of database indexing and the various index types in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Indexes are essential for performance because they reduce the number of rows a query needs to scan.

A database index is a derived structure that maps column values to row locations, trading storage and write cost for faster reads. There are several index types that serve different purposes.

A primary index enforces uniqueness and often serves as the clustered index.

A clustered index defines the physical order of rows and is ideal for range queries and ordered scans.

A non-clustered index stores pointers to rows separately from the table and supports filtering, lookups, and joins on non-primary columns.

Dense indexes contain one entry per row and provide precise access, but come with higher storage and maintenance costs.

Sparse indexes contain fewer entries and rely on proximity to resolve queries, offering lower overhead but less precision.

Filtered indexes only include rows that meet a specific condition, reducing size and improving performance on focused queries.

Covering indexes include all columns needed for a query, allowing the database to return results without touching the base table.

Function-based indexes store computed values and optimize queries that filter or sort on transformed expressions.

Full-text indexes support tokenized and phrase-based search across unstructured text fields.