Every time a user opens an app, browses a product page, or scrolls a social feed, there’s a system somewhere trying to serve that request fast. Mostly, the goal is to serve the request predictably fast, even under load, across geographies, and during traffic spikes.

This is where caching comes in.

Caching is a core architectural strategy that reduces load on the source databases, reduces latency, and creates breathing room for slower, more expensive systems like databases and remote services.

If done correctly, caching can deliver great gains in performance and scalability. However, if implemented incorrectly, it can also cause bugs, stale data, or even outages.

Most modern systems rely on some form of caching: local memory caches to avoid repeat computations, distributed caches to offload backend services, and content delivery networks (CDNs) to push assets closer to users around the world.

However, caching only works if the right data is stored, invalidated, and evicted at the right time.

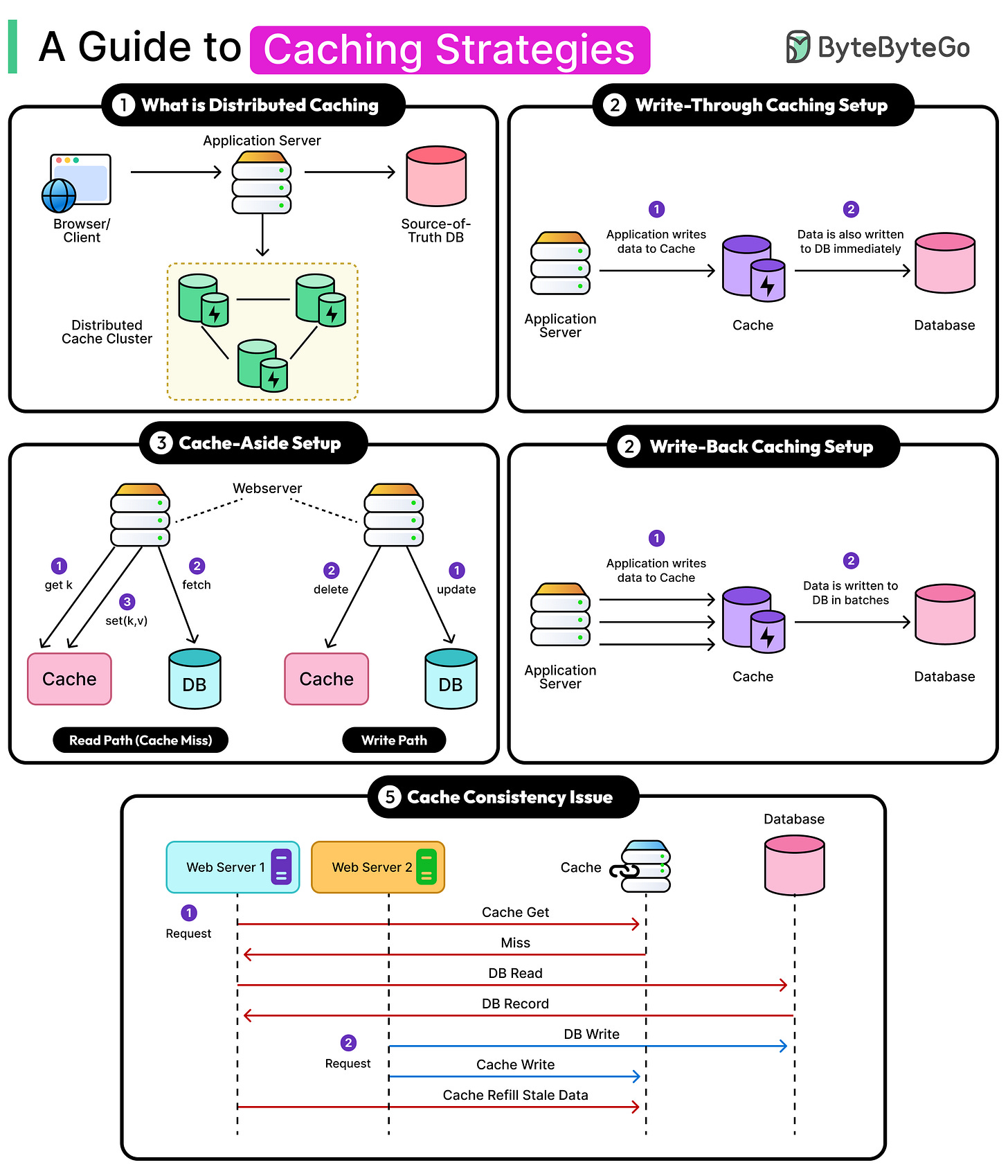

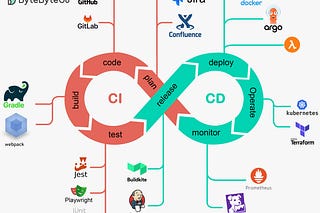

In this article, we will explore the critical caching strategies that enable fast, reliable systems. We will cover cache write policies like write-through, cache-aside, and write-back that decide what happens when data changes. Each one optimizes for different trade-offs in latency, consistency, and durability. We will also look at other distributed caching concerns around cache consistency and cache eviction strategies.

Caching Write Strategies

We all know that caching helps reduce read load, but things get interesting when the system needs to handle writes.

How should a cache behave when new data is written?

Should it update the cache, the backing database, or both?

The answers depend on the write policy in place. Different strategies offer different trade-offs.

Let’s walk through the three most common strategies:

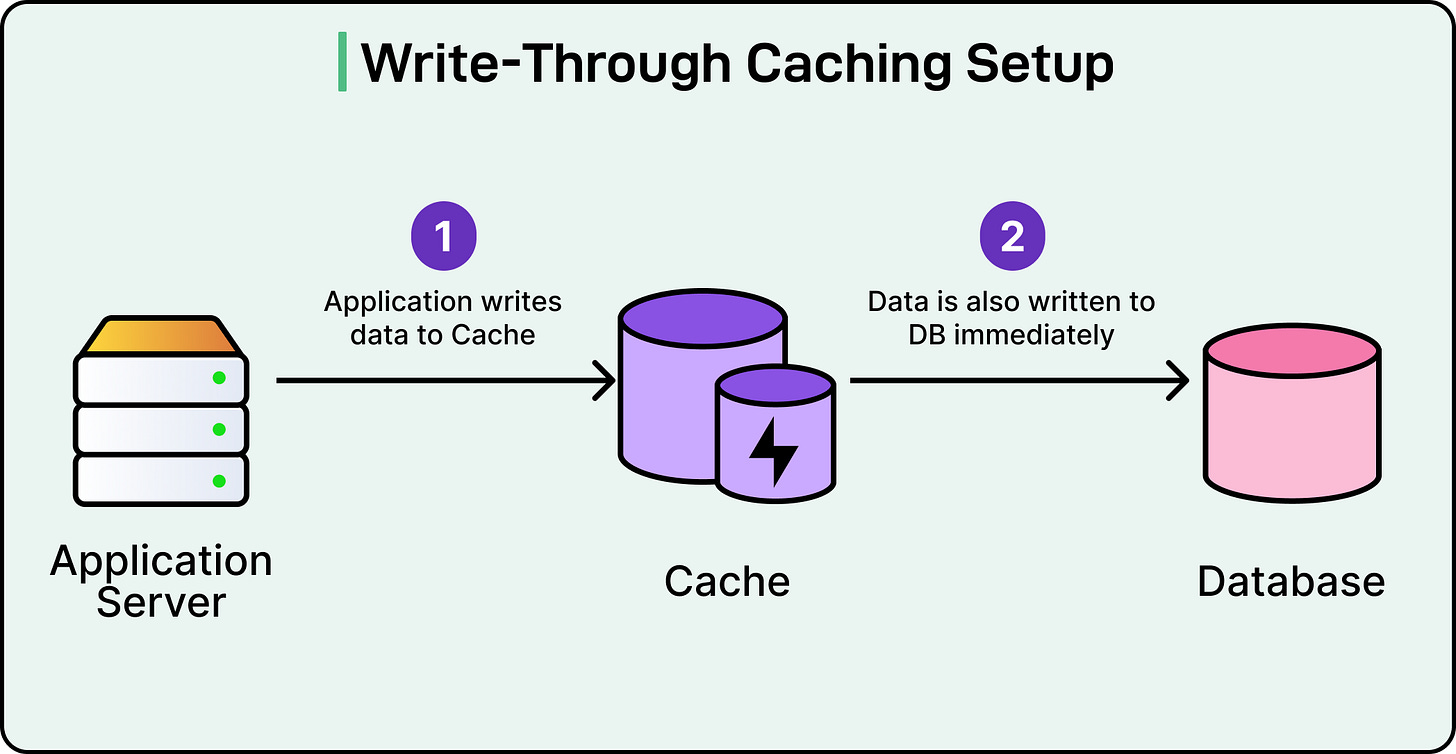

1 - Write-Through Caching

In write-through caching, every write goes through the cache before it hits the database layer.

When the application writes data, the cache stores it and immediately forwards the write to the database. The write isn’t considered successful until both the cache and the database acknowledge it.

See the diagram below:

This approach keeps the cache and the source of truth database in sync at all times. A read immediately after a write will always see the latest value.

Some benefits of this approach are as follows:

Strong consistency between cache and database.

Simplifies cache reads by always trusting the cache.

Reduces stale data risks.

However, there are also trade-offs:

Slower writes where every write hits two systems.

Higher write amplification, where updates always go to both layers.

It can become a bottleneck if the database is slow.

This approach works well in systems that need cache accuracy above all else and read-heavy systems with moderate write volume. For example, use cases like user profiles, product catalogues, or feature flag systems.

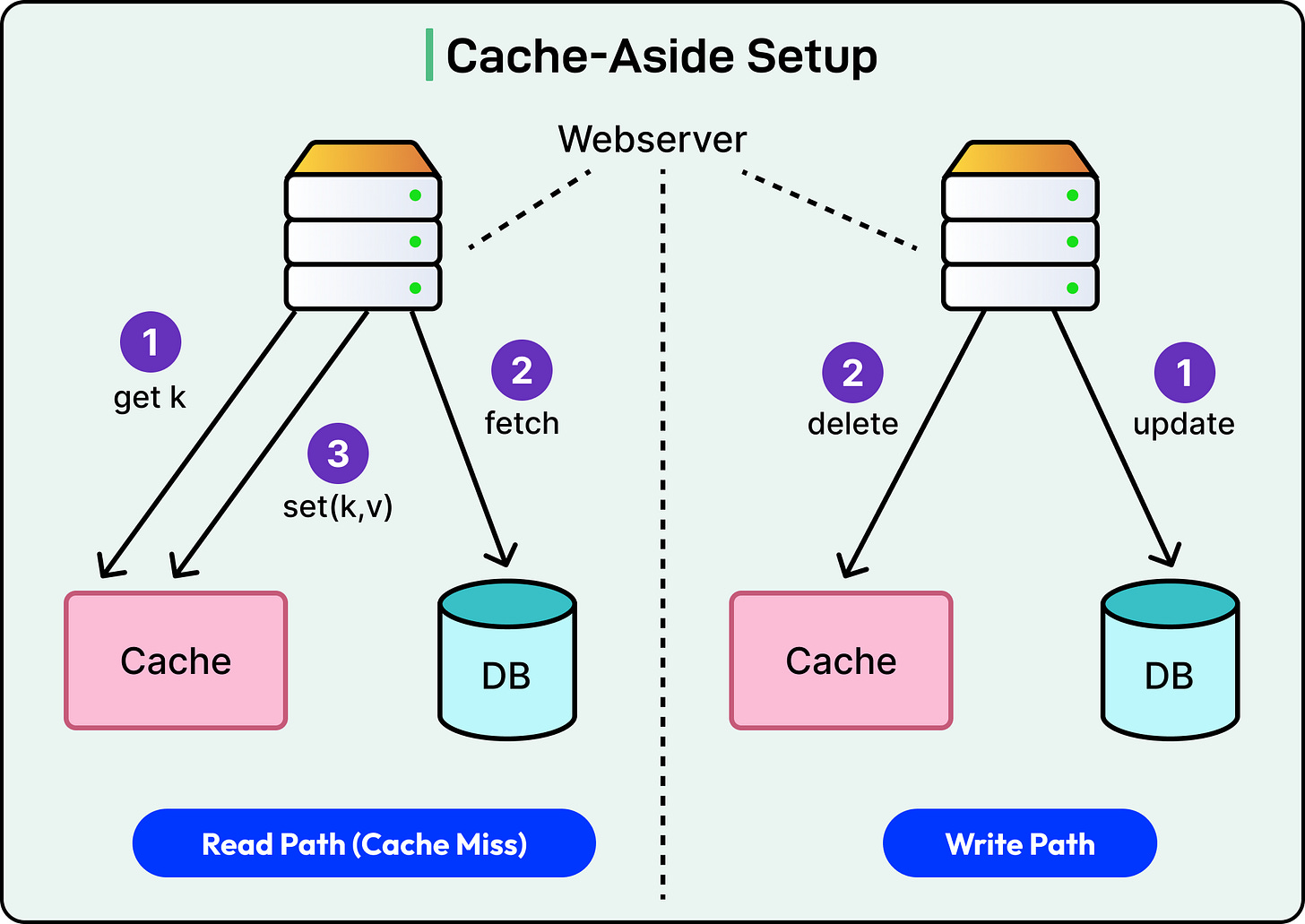

2 - Cache Aside Approach

The Cache-Aside is the most common approach when it comes to caching.

The write goes straight to the database. It generally updates the database and invalidates the cache. However, the cache doesn’t store the new value right away. If the data gets read later, the cache loads it from the database and stores it for future use.

This avoids caching data that might never be read. It helps keep the cache “clean,” focused only on hot or frequently accessed data.

See the diagram below:

The main benefits of this approach are as follows:

Reduces cache pollution from rarely used data

Lower cache write load

Good for write-heavy, read-sparse patterns

Some trade-offs are:

First read after a write causes a cache miss.

Increased latency on read-after-write operations.

Temporary inconsistency between cache and source of truth.

It works well in systems with high write volume, but low read-after-write probability. Think of logging systems, audit trails, or cold storage access patterns.

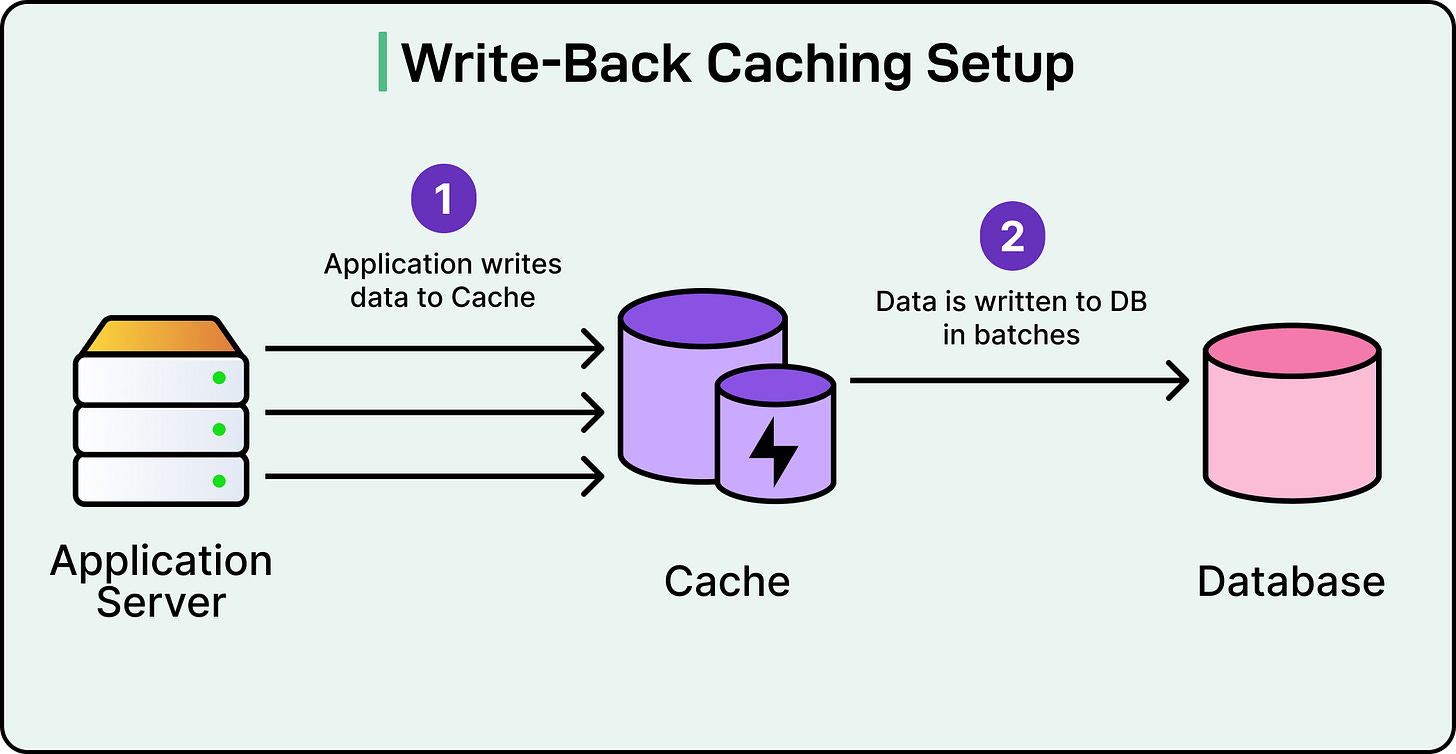

3 - Write-Back Caching

Write-back caching flips the model. The cache becomes the primary write target, and the database lags.

The application writes to the cache. The cache holds the new data and pushes it to the database later. It can be based on a timer, after a batch threshold, or during eviction.

This gives fast write performance, since the application doesn't wait for the database. However, the cache now holds a state that hasn’t yet reached the source of truth.

See the diagram below:

The benefits are as follows:

Fastest write latency.

Reduces write load on the database.

Good for bursty write traffic.

However, there are also trade-offs:

Risk of data loss if the cache crashes before flushing.

Harder to ensure durability and consistency.

Requires careful tuning, replication, or logging mechanisms.

It works well in systems that can tolerate eventual consistency. For example, it can be ideal for systems that have soft-state data like counters, game state, or analytics. Also, it may be suitable for use cases with aggressive performance needs.

Comparisons and Trade-Offs

Each of these strategies solves a different problem. Choosing the right one depends on what the system values most.

Write-through favors correctness. Cache-aside optimizes for clean caching. Write-back chases performance, but it comes with sharp edges.

No single policy works everywhere, and real-world systems often combine them. For example, a system might use write-through for critical metadata and write-back for user-generated metrics. Developers should choose based on the system’s tolerance for stale reads, its durability guarantees, and performance targets.

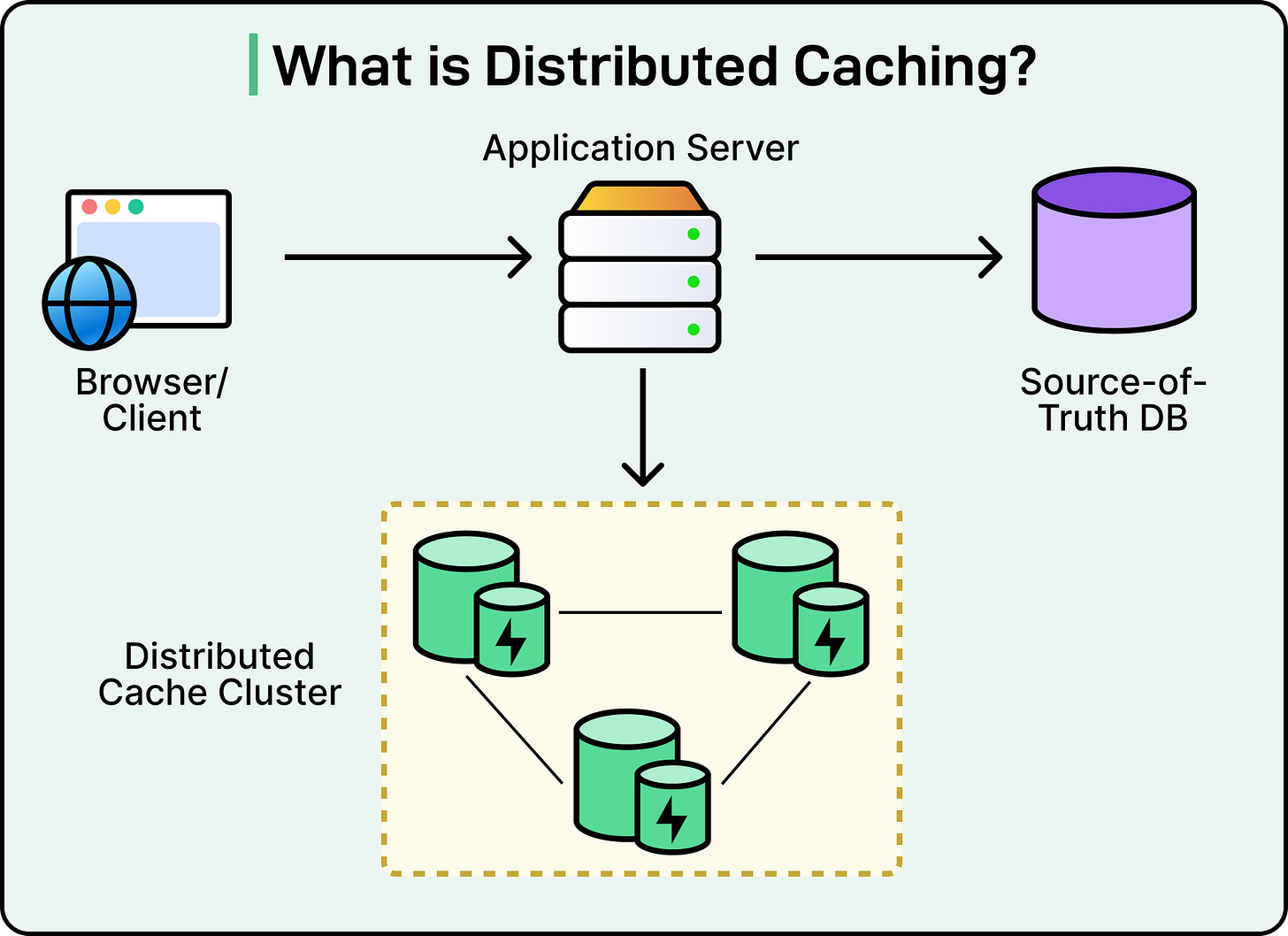

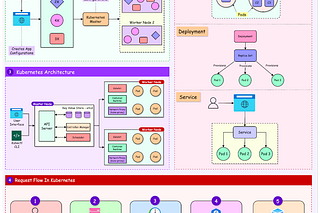

Distributed Cache Consistency Issues

A single cache sitting next to an app server is easy to deal with. However, as soon as caching spreads across multiple nodes, regions, or services, consistency gets harder to maintain.

Distributed caches introduce coordination problems. When multiple clients, or worse, multiple services in different data centers, read and write the same data, caches can go out of sync. The result is that users see stale data, race conditions pop up, and debugging gets painful.

See the diagram below:

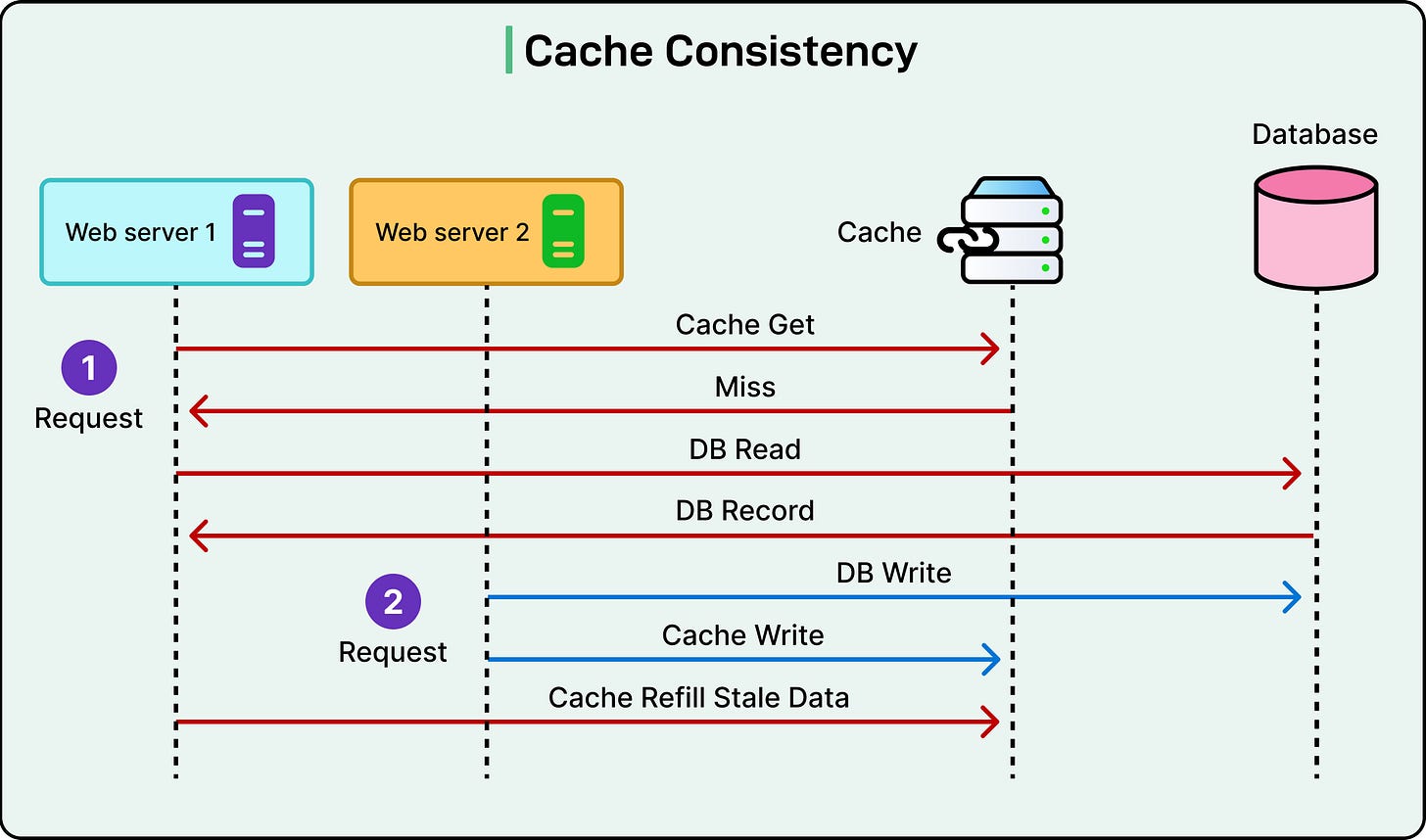

Cache Inconsistency

Distributed caches drift out of sync for many reasons:

Stale reads: A client reads data from a cache node that hasn’t been updated yet after a write.

Concurrent updates: Two services write to the same key from different nodes. Only one version ends up in the cache, and it might be the wrong one.

Partial invalidation: A service updates the database but fails to invalidate the cache on every node.

Network delays or failures: A publish/subscribe message meant to trigger cache updates gets lost or delayed. Some nodes stay stale longer than others.

See the diagram below to understand how cache inconsistency can occur:

It’s tempting to aim for strong consistency, where every cache node always reflects the latest database state. But in practice, strong consistency is expensive and hard to guarantee across regions.

Most distributed systems settle for eventual consistency. As long as updates propagate and caches eventually reflect the truth, things keep working. This trade-off works fine in feeds, counters, and user settings, but can be dangerous in financial systems or shared inventories.

Cache Invalidation and Synchronization Techniques

The key to managing distributed cache consistency is communication. Caches don’t know when data changes unless something keeps them in sync.

Here’s how systems try to keep caches in sync:

Write-through or write-behind caching: These patterns help by ensuring the cache sees every write. With write-through, the cache remains in sync because it handles the write operation. With write-behind, the cache buffers writes and sends them to the database later.

Explicit invalidation: The application updates the database and then sends a signal to all cache nodes to evict or refresh the key.

Pub/Sub systems: Some systems publish a message on a topic (for example, “user:1234:updated”) when data changes. All cache nodes subscribed to that topic evict or reload the relevant key.

Versioned keys or timestamps: Instead of mutating existing keys, some systems write a new version and let old cache entries expire naturally. This avoids races but requires cache consumers to use the latest version of the data.

Even with these tools, inconsistencies still creep in. Read-after-write gaps, race conditions between invalidation and repopulation, and partial failures are common.

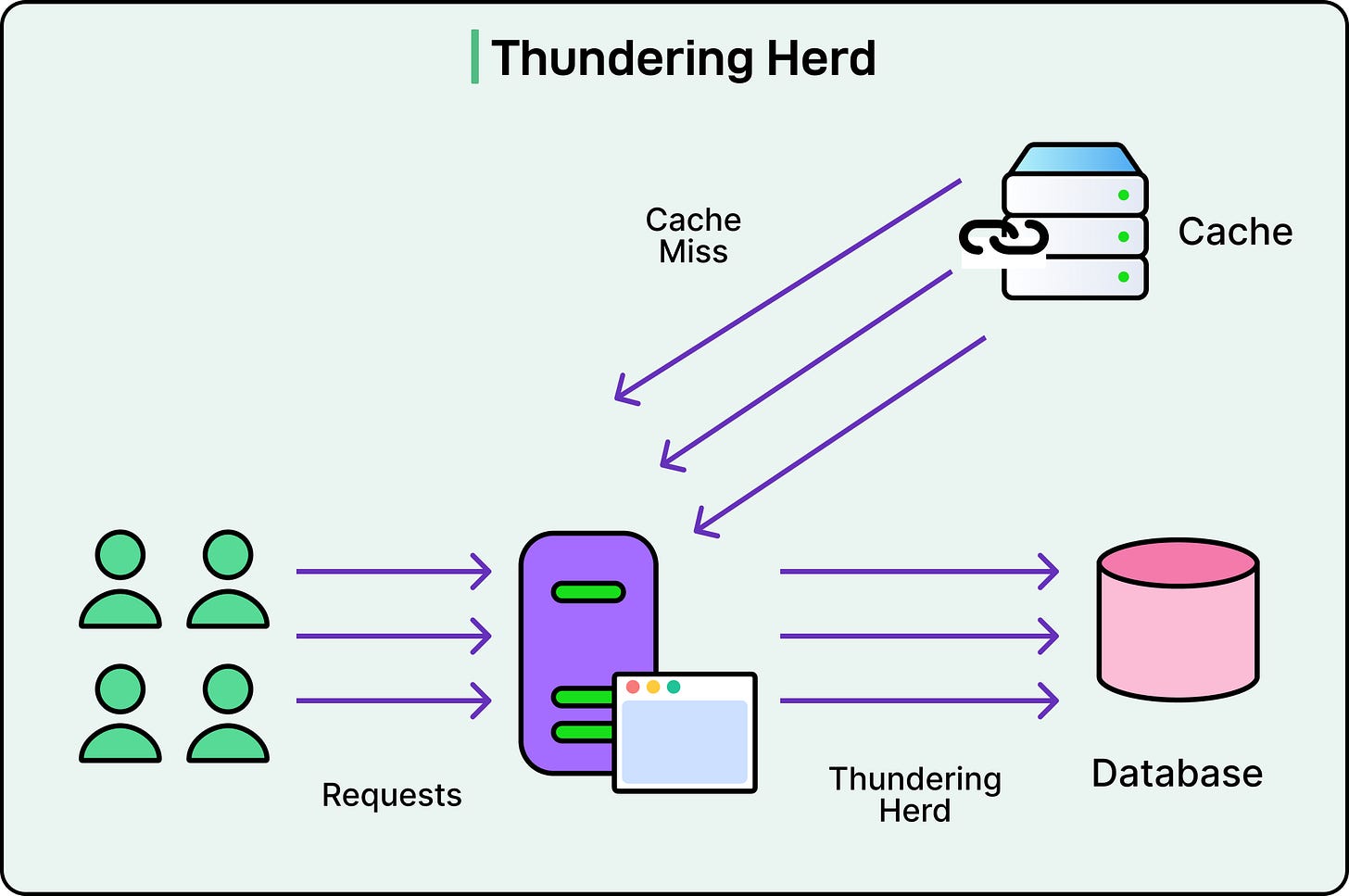

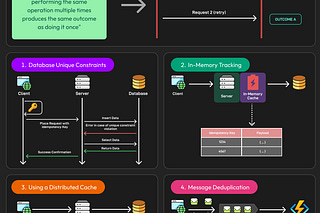

The Thundering Herd Problem

Sometimes the problem isn’t stale data but too many clients asking for fresh data at once.

When a popular cache entry expires, every request that comes in hits the cache and misses. Suddenly, thousands of clients hammer the backend with the same request. This is known as the thundering herd prm.

See the diagram below:

It gets worse during deployments, cold starts, or traffic spikes. The backend struggles, the latency spikes, and the user experience is impacted.

Solutions usually fall into three buckets:

Request coalescing: Only one request fetches the data from the backend. The others wait for the result.

Cache pre-warming: Load popular keys into the cache ahead of time at specific points such as after deploys, during traffic ramp-up, or before promotions.

Locking or token-based refresh: The first request that sees a miss sets a lock (or token) for that key. Others back off and retry after a delay. This prevents every request from reloading the same data.

Cache Eviction Policies

When a cache runs out of space, some entry has to be removed. The cache eviction policy decides which record gets kicked out of the cache to make room for new data. This choice has a direct impact on cache hit ratio, memory usage, and system performance.

The right policy depends on access patterns. Some apps repeatedly access the same few items. Others show bursts of activity on trending data. A smart eviction policy matches the workload’s shape and avoids keeping cold or irrelevant data around.

Let’s break down the most common eviction strategies:

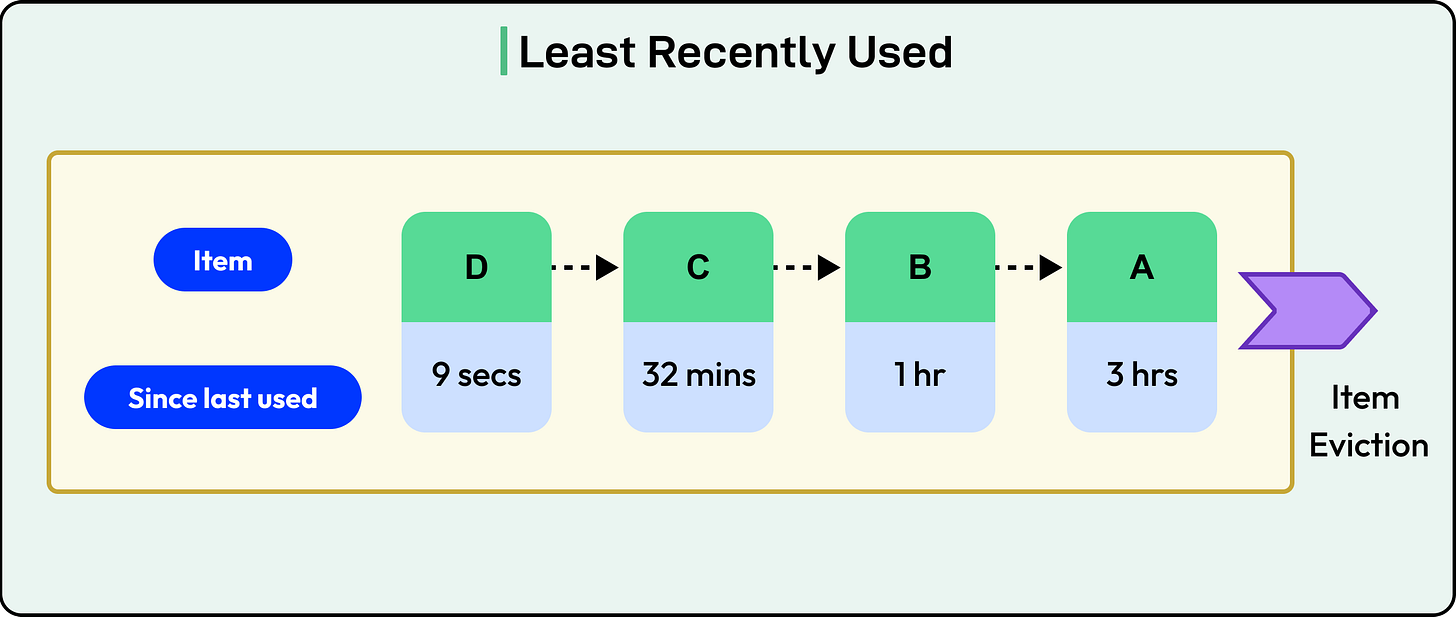

1 - Least Recently Used (LRU)

LRU assumes that if a key hasn’t been accessed in a while, it’s unlikely to be used again soon. Every time a key is accessed (read or written), it’s marked as "recently used." When space runs out, the key that hasn’t been used for the longest time is evicted.

LRU works well for temporal locality, or the idea that recently accessed items are more likely to be accessed again soon. This pattern shows up in many applications: user sessions, search results, or paginated feeds.

Implementation details are as follows:

Most systems use a doubly linked list paired with a hash map for O(1) operations.

On access, the key is moved to the front of the list. Evictions happen from the back.

Real-world caches like Redis and Memcached use variations like approximate LRU to reduce overhead. For example, Redis samples a few keys at random and evicts the least recently used one among them.

This policy works best for web sessions and dashboards, product pages with recent browsing patterns, and API responses with short-term relevance.

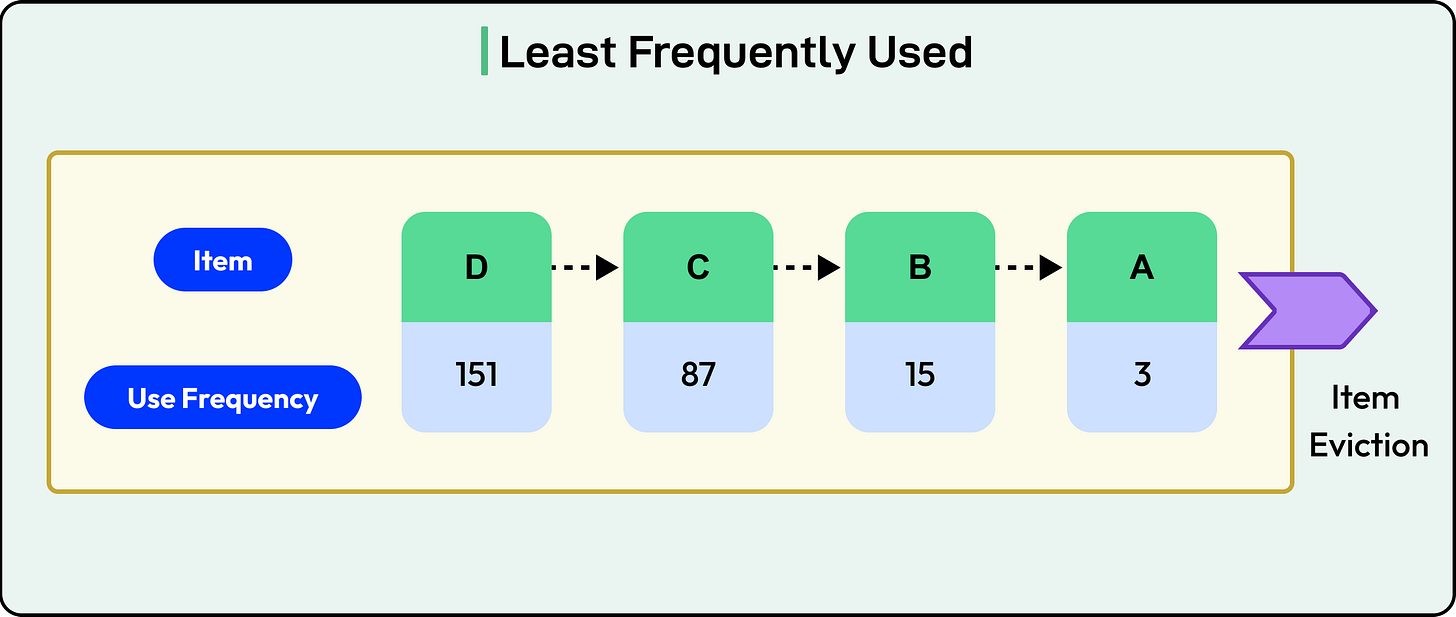

2 - Least Frequently Used (LFU)

LFU takes a different approach: it tracks how often each item is accessed, and evicts the least-used ones.

Each key has a counter that increments with every access. When the cache needs space, it removes the key with the lowest count.

LFU favors frequency locality. Keys that are consistently popular stay in the cache, even if they haven’t been accessed recently. This is ideal when certain items have long-term value or repeated access.

Implementation details are as follows:

Maintaining exact counts for all keys can be expensive.

Systems often use aging counters or decay mechanisms to avoid keeping old popular items forever.

This policy works best for trending content, hotspot detection in large datasets, and long-running workflows with stable patterns

3 - First-In First-Out (FIFO)

FIFO is exactly what it sounds like: the first item inserted is the first one evicted.

Each new key goes to the end of a queue. When the cache is full, the item at the front of the queue is removed regardless of whether it’s still in active use.

FIFO is simple. It doesn’t require tracking usage or access frequency. That makes it easy to implement and fast to run.

However, it works barely for a few use cases, such as:

Temporary staging buffers.

Prefetch queues where access order mirrors insertion order.

Systems where caching is used for throughput smoothing, not reuse.

FIFO struggles because it ignores whether an item is useful or not and evicts data blindly, even if the item was accessed a moment ago. In most workloads, FIFO underperforms LRU and LFU.

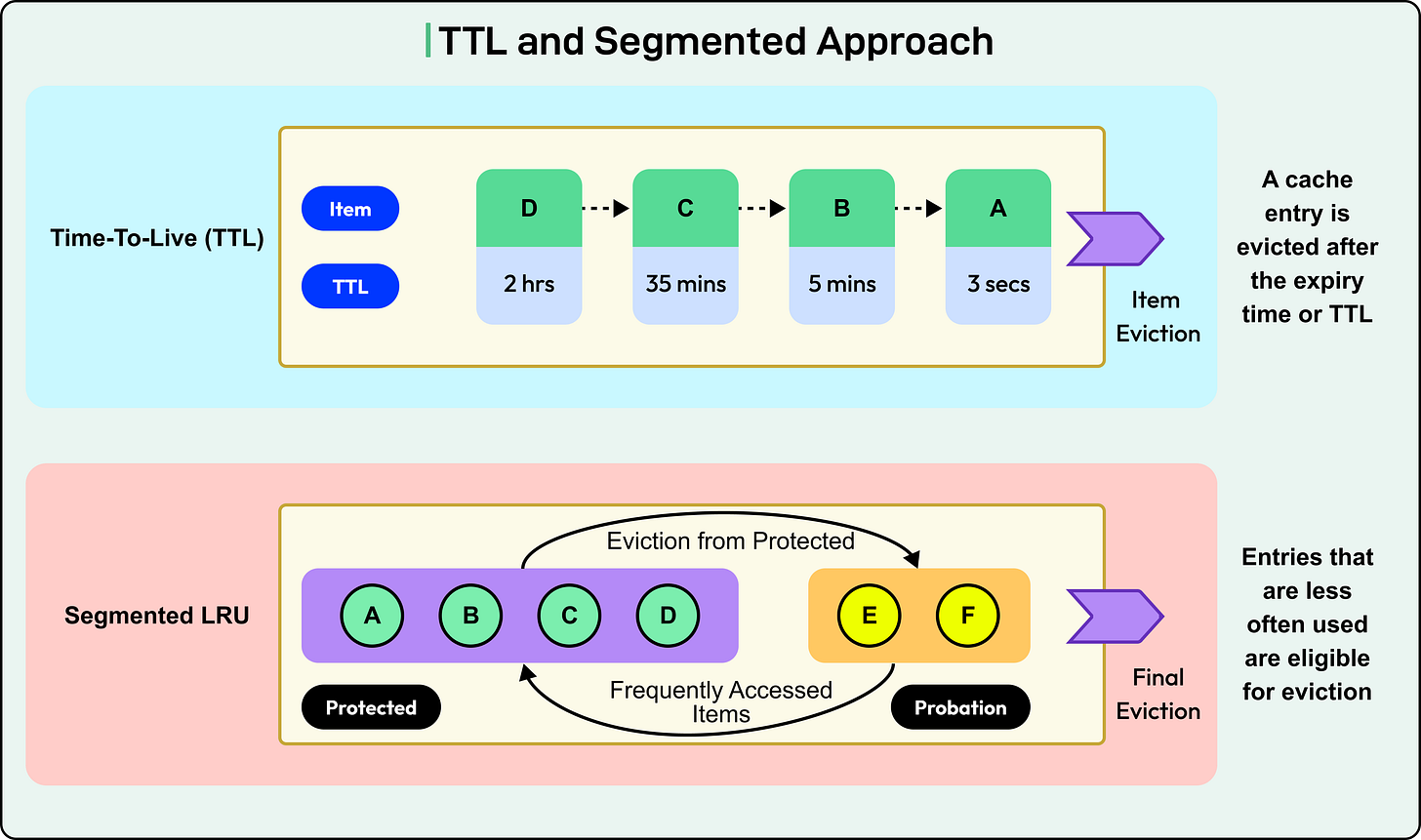

4 - Advanced and Hybrid Eviction

Real-world caching often demands more nuance. Some systems combine multiple signals, such as recency, frequency, size, and cost, to make smarter eviction decisions.

A few popular hybrid approaches are as follows:

LRFU (Least Recently/Frequently Used): Blends recency and frequency with a configurable weighting factor. This lets the system adjust based on observed behavior.

ARC (Adaptive Replacement Cache): Maintains two lists, one for recently accessed items and another for frequently accessed ones. ARC adapts over time, allocating more space to the list that produces better results.

Some other important factors that are considered during cache eviction are:

TTL (Time to Live): Expiry-based eviction works alongside these policies. Keys expire after a set time, even if they’re still in the cache.

Object size or cost of recomputation: Some caches assign weights to keys based on how expensive they are to fetch or how large they are in memory. Eviction then prioritizes keys that free up more space or cost less to re-fetch.

Segmentation and priority tiers: Caches can divide their memory into multiple segments (for example, separating short-term and long-term items) and apply different policies to each.

See the diagram below for reference:

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at caching strategies, distributed cache consistency, and cache eviction policies in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Caching improves performance by reducing load on slow or remote systems, but requires careful design to avoid stale data and subtle bugs.

Write-through caching updates both the cache and the backing store synchronously, offering strong consistency but higher write latency.

The Cache-aside approach invalidates the cache on writes, reducing cache pollution but risking cache misses on read-after-write scenarios.

Write-back caching writes to the cache first and flushes to the database later, enabling low-latency writes but increasing the risk of data loss if the cache fails.

Distributed caches face consistency challenges like stale reads, missed invalidations, and race conditions, especially when multiple clients update the same data.

Pub/Sub systems, versioned keys, and explicit invalidation calls help synchronize distributed caches, though none fully eliminate inconsistency risks.

The thundering herd problem occurs when many clients request the same key after expiration, overwhelming the backend. Techniques like request coalescing and pre-warming can mitigate it.

LRU evicts the least recently used items, making it effective for workloads with temporal locality.

LFU evicts the least frequently accessed items, ideal for workloads with long-term hotspots but harder to implement efficiently.

FIFO evicts the oldest inserted items regardless of usage, which is simple but often performs poorly under real-world access patterns.

Hybrid policies like LRFU and ARC adapt to changing access patterns, balancing recency and frequency for better long-term efficiency.

Eviction decisions can also factor in TTLs, item size, and recomputation cost, helping the cache retain high-value data under pressure.