Modern databases don’t run on a single box anymore. They span regions, replicate data across nodes, and serve millions of queries in parallel.

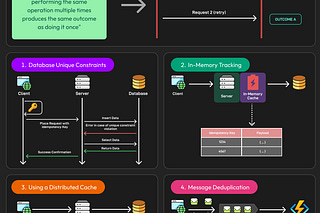

However, every time a database tries to be fast, available, and correct at once, something has to give. As systems scale, the promise of fault tolerance collides with the need for correctness. For example, a checkout service can’t afford to double-charge a user just because a node dropped off the network. But halting the system every time a replica lags can break the illusion of availability. Latency, replica lag, and network partitions are not edge cases.

Distributed databases have to manage these trade-offs constantly. For example,

A write request might succeed in one region but not another.

A read might return stale data unless explicitly told to wait.

Some systems optimize for uptime and accept inconsistencies. Others block until replicas agree, sacrificing speed to maintain correctness.

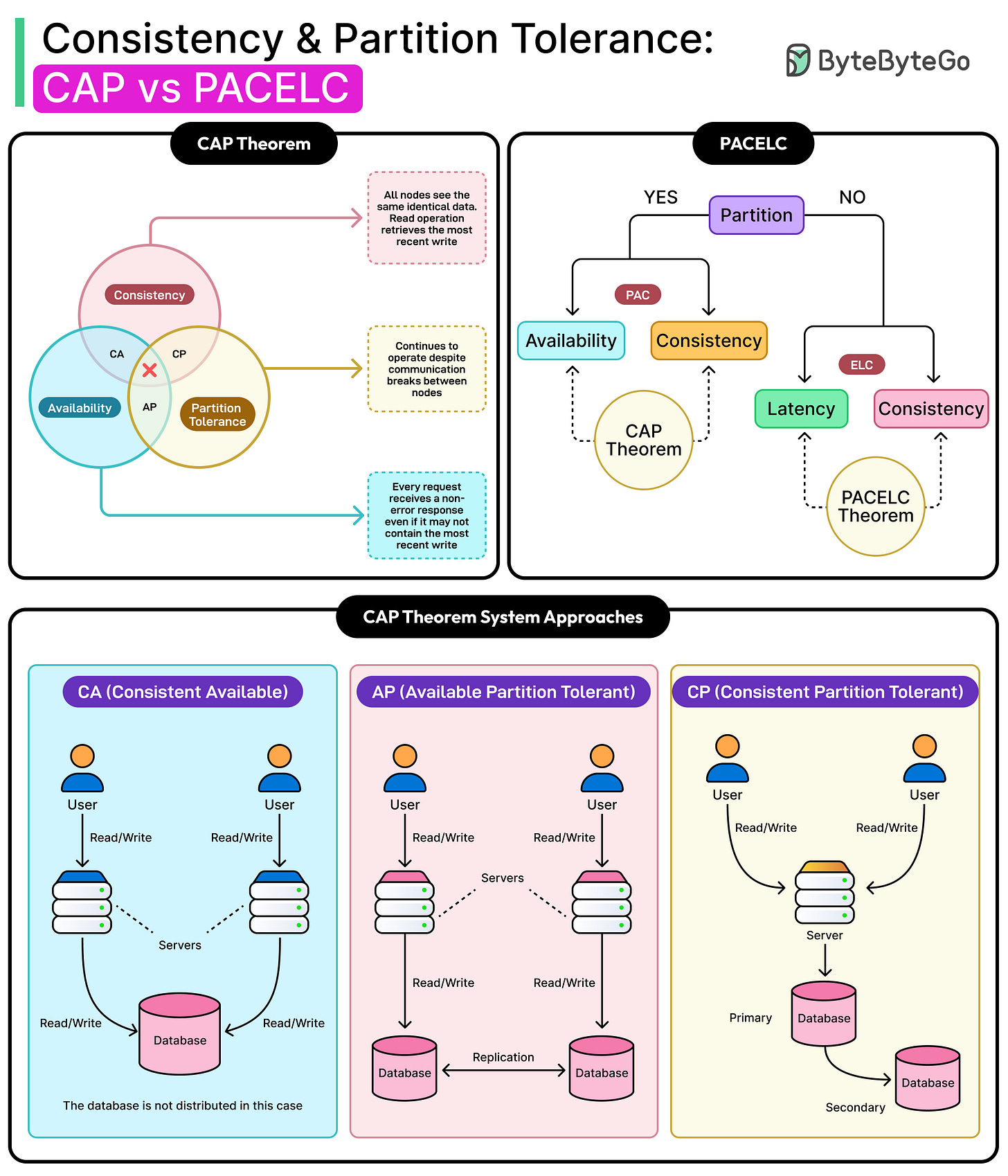

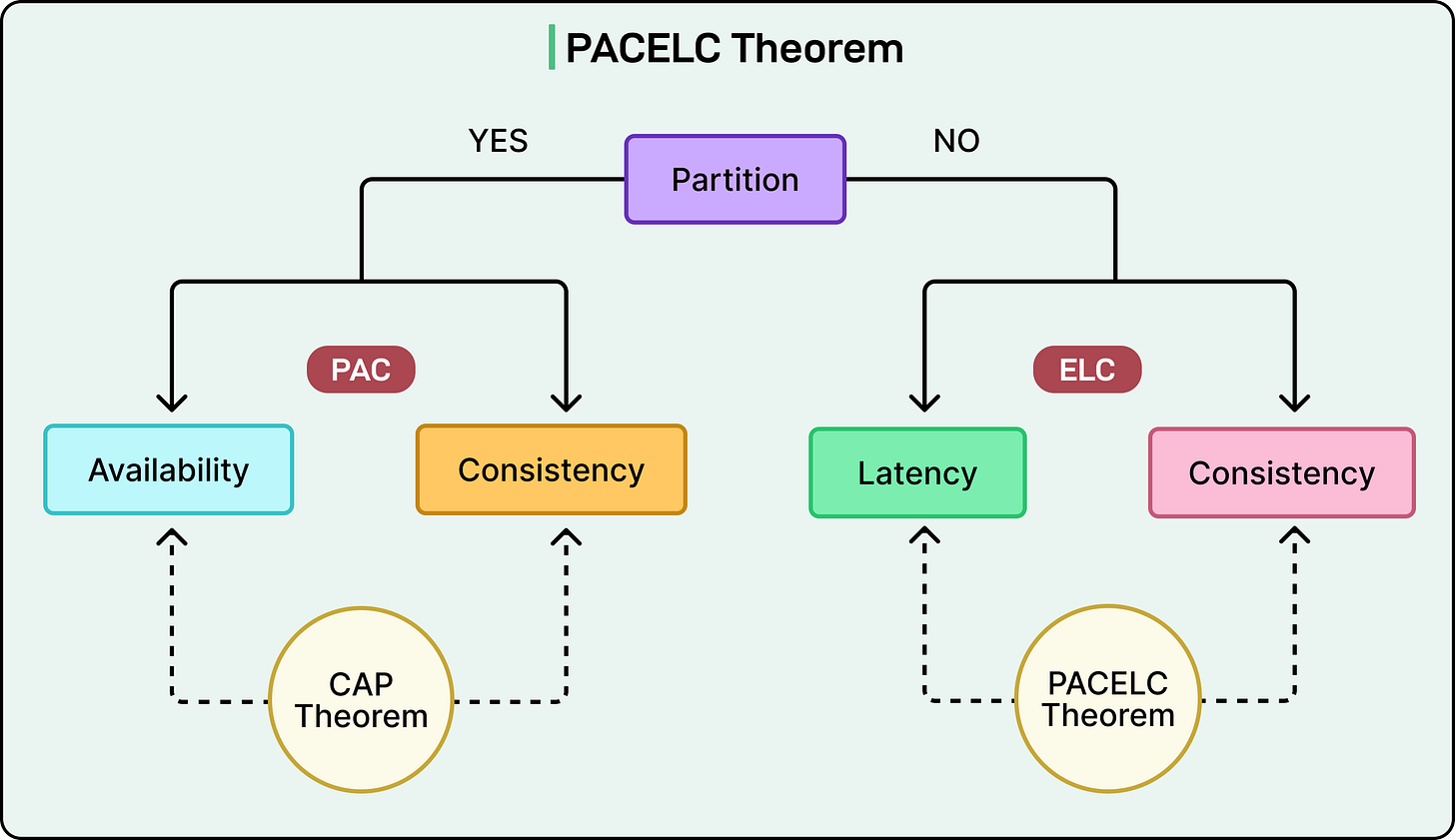

Two models help make sense of this: the CAP theorem and the PACELC theorem. CAP explains why databases must choose between staying available and staying consistent in the presence of network partitions. PACELC extends that reasoning to the normal case: even without failure, databases still trade latency for consistency.

In this article, we will look at these two models as they apply to real-world database design and understand the various trade-offs involved.

Consistency and Partition Tolerance

Distributed systems often fail because of unclear expectations around what data should look like during failure. Two properties lie at the center of this conversation:

Consistency

Partition Tolerance

Consistency, in the context of distributed systems, refers to a strong and precise guarantee that every read must return the most recent successful write or fail. This is often also called linearizability. It ensures operations appear to execute in a single, globally agreed-upon order. For example, if a user sends a message and then immediately refreshes the screen, a consistent system guarantees that the message shows up on the next read.

This is not the same as eventual consistency, which only promises that replicas will converge to the same value. It is also different from application-level consistency, such as enforcing valid state transitions. In this context, consistency is about time and visibility. It ensures that once a write is acknowledged, all subsequent reads reflect that write, no matter which node serves the request.

Partition Tolerance means the system continues to operate despite broken communication between nodes. These failures happen more often than they should, due to dropped packets, network congestion, zone outages, or misconfigured firewalls. Any system that runs across multiple machines or locations must assume partitions will occur, and the architecture must be prepared to handle them.

A partition-tolerant system keeps working when parts of the network stop talking to each other. However, there is a trade-off. Such a system needs to give up either availability or consistency during that partition.

This is where things start to get problematic. If two replicas cannot communicate but both continue serving traffic, one of them may return stale or conflicting data. If they stop serving traffic until they can coordinate, the system becomes unavailable. This is not an implementation flaw but a consequence of physical limits. Messages have to cross real wires, and sometimes they get delayed, dropped, or misrouted entirely.

Systems resolve this trade-off differently.

Some choose availability, allowing updates in both partitions and resolving conflicts later.

Others choose consistency, blocking requests when they cannot confirm quorum.

The right choice depends on the use case. For example, a financial ledger may favor consistency, whereas a product recommendation engine prioritizes availability.

The CAP Theorem

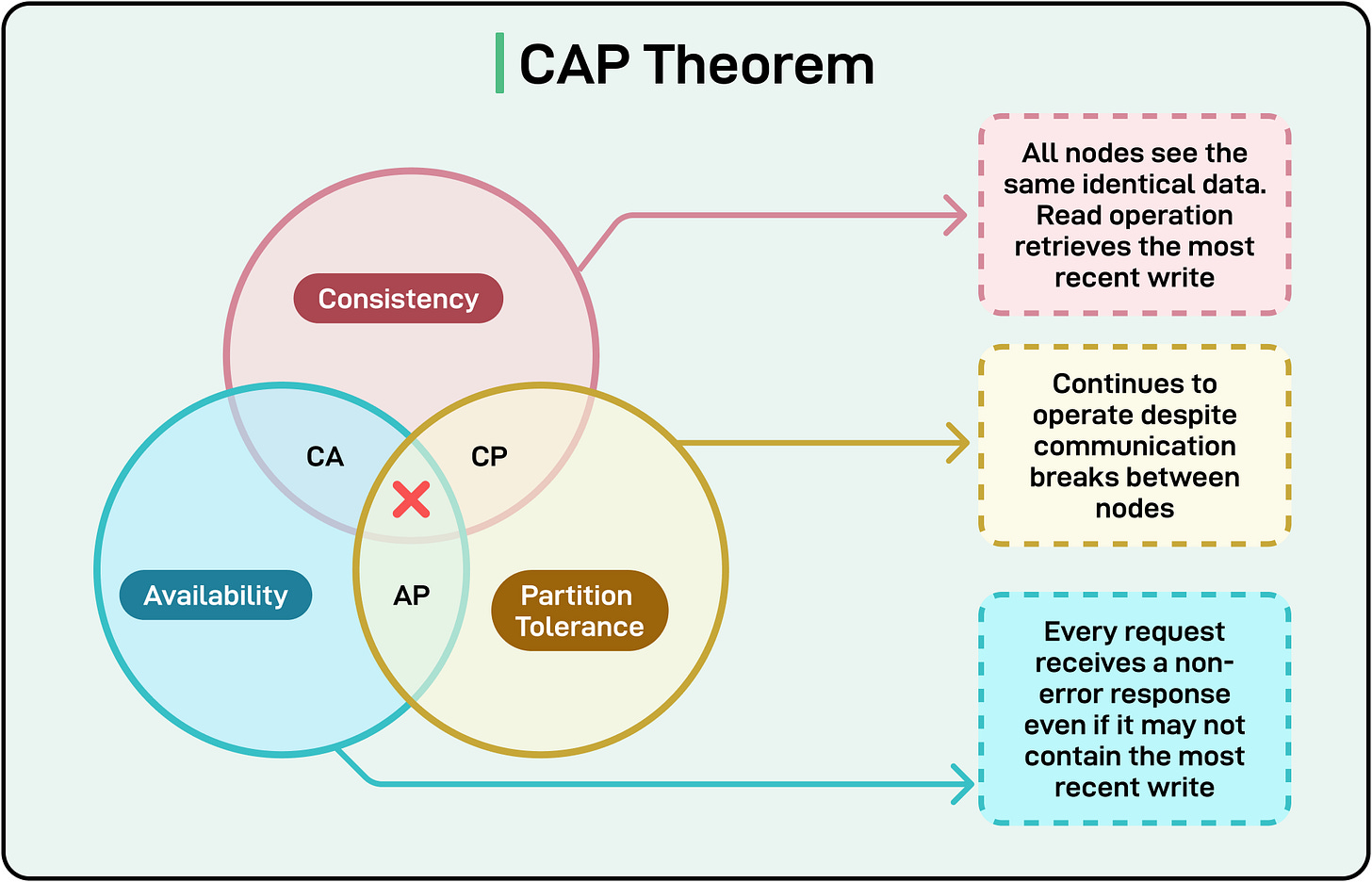

In 2000, Eric Brewer presented the idea that in any distributed system, it is impossible to guarantee consistency, availability, and partition tolerance simultaneously. This idea came to be known as the CAP Theorem.

To understand what the theorem says, it helps to first define the three terms clearly and precisely:

As mentioned, consistency means every read receives the result of the most recent successful write. This is the same strong consistency discussed earlier: a read should never return stale data if a newer value has been acknowledged.

Availability means every request to a non-failing node receives a response, even if it cannot be guaranteed to reflect the most recent write. In other words, the system does not hang, error out, or time out, as long as the request reaches a healthy node.

Partition Tolerance means the system continues operating even when network messages between nodes are lost, delayed, or dropped. Since networks are unreliable by nature, every distributed system must assume that partitions will happen.

The CAP theorem makes a focused claim: if a partition occurs, a distributed system must choose between consistency and availability. Note that the theorem does not say that only two of the three properties can ever be present. It mentions that during a network partition, which is often an inevitable condition in real-world systems, the system must give up either consistency or availability.

This constraint results in the following scenarios:

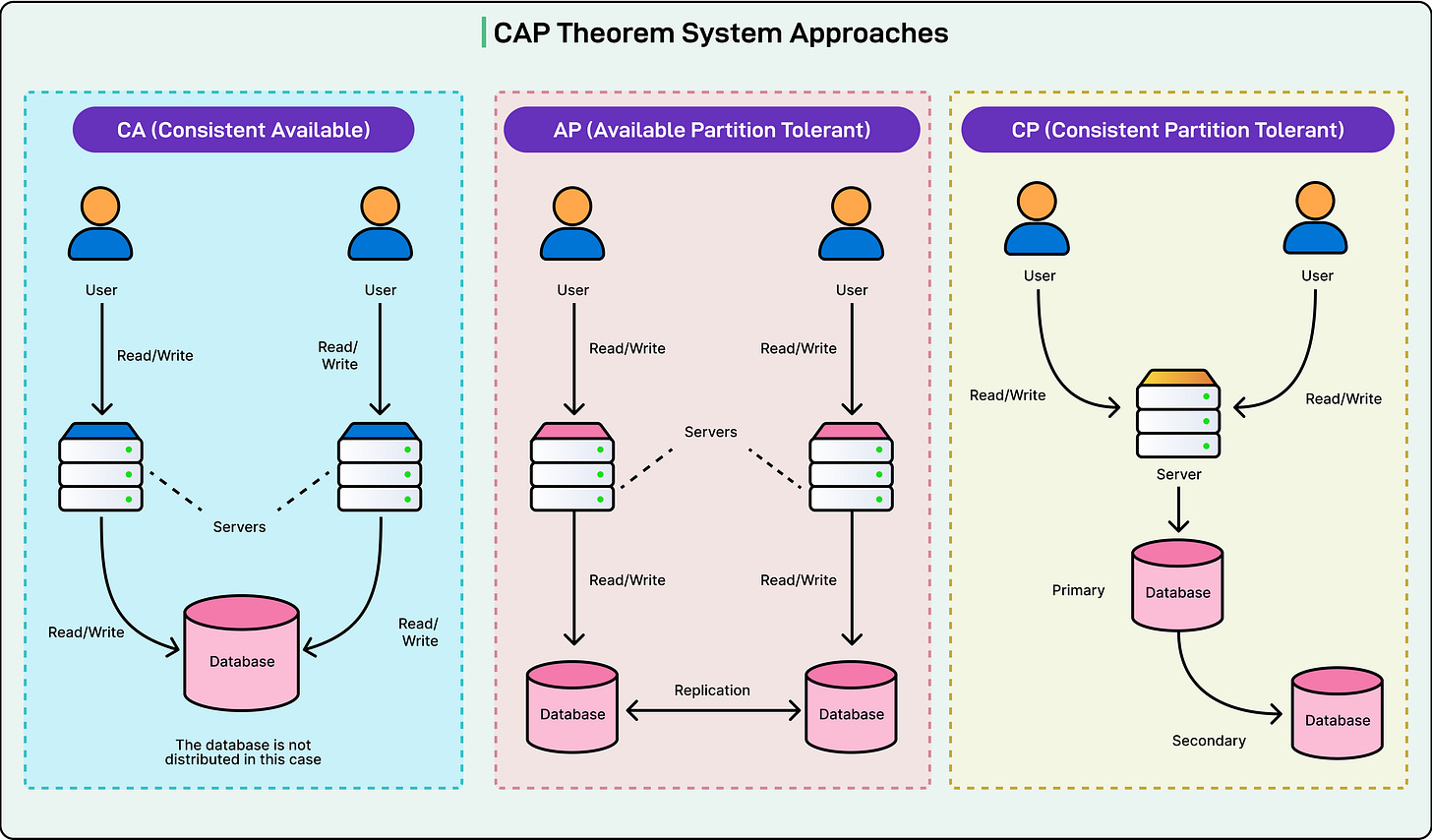

A CP system will prioritize consistency. If a node cannot verify that its peers have seen a write, it will refuse to serve requests or block writes until coordination is restored. This preserves data correctness but sacrifices availability during a partition.

An AP system will prioritize availability. It continues to serve requests even when coordination with other nodes is not possible. This keeps the system responsive but risks serving stale data or accepting conflicting writes.

A common misunderstanding is the idea that systems “pick any two” of the three properties. That framing misses the conditional nature of the theorem. The trade-off only activates during a partition. In the absence of failure, a well-designed system can be consistent and available. But the moment a partition hits, one guarantee must yield.

See the diagram below that clarifies this scenario:

CAP Theorem In Practice

The real test of any distributed system doesn’t happen on a clean day.

When messages stop flowing between nodes, either due to a dropped link, an overloaded switch, or a misconfigured firewall, the system enters uncertain territory. It can no longer guarantee that every part of the cluster sees the same data. This is where the CAP theorem becomes more than theory. Design decisions show up as user-facing behavior, and trade-offs start costing real money.

In a CP system, the priority is clear: preserve consistency at all costs. When a partition occurs, nodes that cannot reach a quorum will refuse to serve writes. Sometimes, they may block reads as well. In other words, the system avoids making decisions it can’t guarantee are safe.

For example, Zookeeper uses majority-based consensus (via Zab, its coordination protocol). If a node can’t see the majority of the ensemble, it halts operations. From the outside, this looks like downtime. But internally, it’s a deliberate step to avoid split-brain scenarios where two sides accept conflicting updates.

In contrast, AP systems lean into availability. If a client reaches a live node, that node accepts the write, even if it has no idea what the other half of the system is doing. Once the partition heals, the system attempts to reconcile conflicting updates. This might involve last-write-wins, custom conflict resolution logic, or version vectors like vector clocks that track causality.

Systems like Amazon’s Dynamo, which inspired many NoSQL databases, follow this model. They favor responsiveness and durability, even if it means temporarily sacrificing consistency.

This trade-off hits hardest in user-facing systems. Consider a shopping cart that disappears mid-checkout, a message that gets overwritten, or a financial transaction that shows different states on different devices.

All of these are symptoms of partition-related choices. Engineers must think carefully about consistency models, not just in terms of CAP, but also along the spectrum: linearizability (strict ordering), sequential consistency (agreed-upon order, not necessarily real-time), causal consistency (honors cause-effect relationships), and eventual consistency (updates will converge eventually).

No model is inherently superior. Each fits different application goals. Some examples are as follows:

For a coordination service like Zookeeper, inconsistency can be catastrophic. CP is the only viable choice.

For a recommendation feed or product listing service, a bit of temporary inconsistency is tolerable. AP or eventually consistent systems make sense.

For many distributed databases, like Apache Cassandra, the system also exposes tunable consistency, letting developers choose the level of coordination per read or write.

The PACELC Theorem

The CAP theorem explains how systems behave when there is a failure, but it leaves a gap. Most of the time, distributed systems may not experience partitions. Networks work, and nodes stay in sync.

In such a situation, the question arises: What trade-offs do systems make even when everything is healthy?

This is where the PACELC theorem, proposed by Daniel Abadi, helps. It builds on CAP by adding an important dimension: the cost of consistency during normal operation.

The model reads like a decision tree.

If a Partition occurs (P), then the system must choose between Availability (A) and Consistency (C).

Else (E), when the system is healthy, it must choose between Latency (L) and Consistency (C).

This small extension captures a much broader reality. Systems that prioritize availability under partition also tend to prioritize low latency under normal conditions. And systems that prefer consistency when the network is broken usually make the same choice when the network is fine. PACELC brings these consistent preferences into the spotlight.

Here’s how it plays out in real systems:

DynamoDB and Apache Cassandra can be considered to fall under PA/EL. They prioritize availability when a partition occurs and optimize for low latency during normal operation. These systems use quorum reads and writes, but they allow tunable consistency and fast local responses. Conflict resolution and convergence are handled asynchronously.

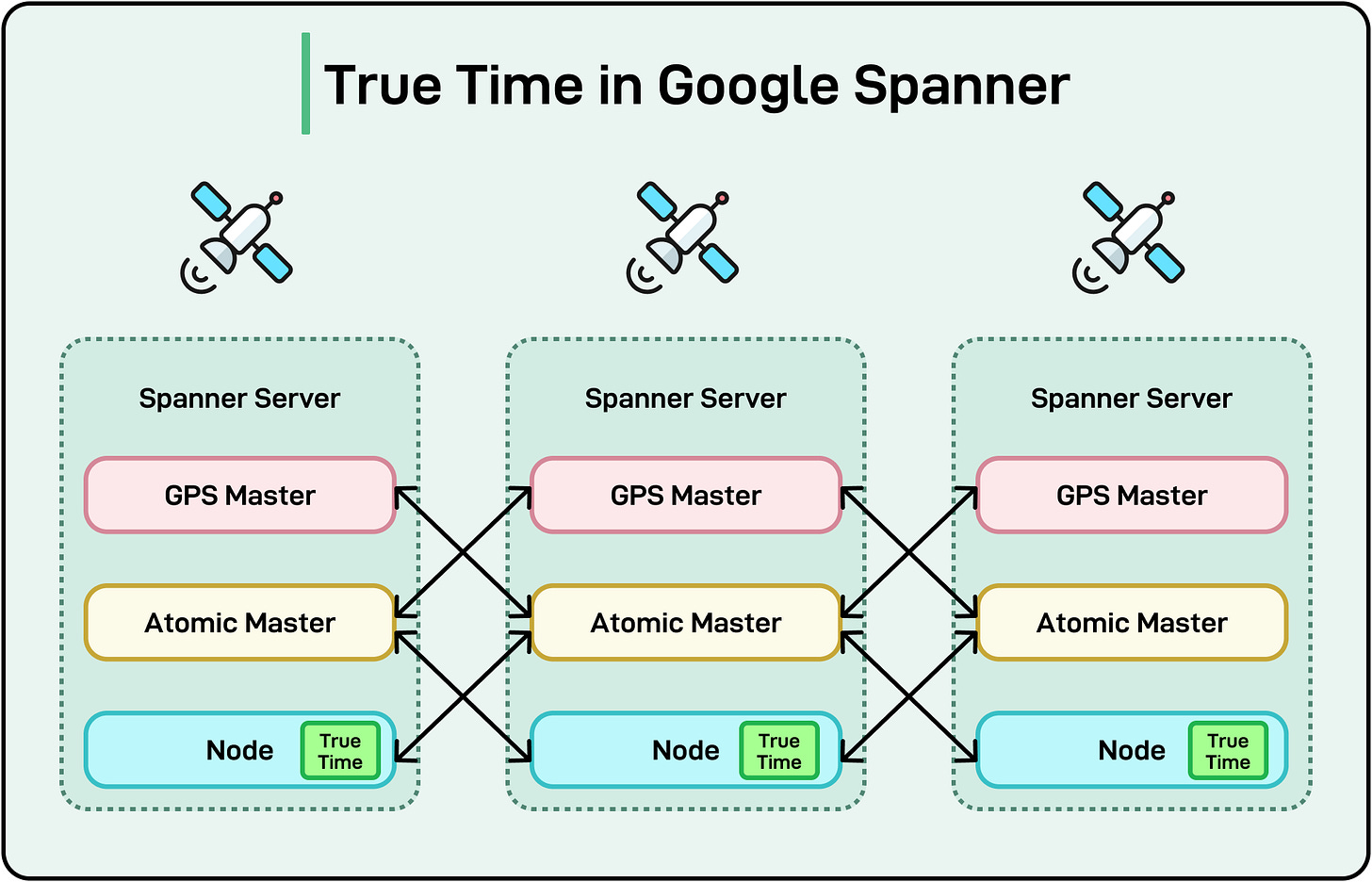

Spanner, Google’s globally distributed SQL database, is a clear PC/EC system. It favors consistency during partitions and continues that commitment even when everything is running normally. Spanner uses tightly synchronized clocks (via TrueTime) and synchronous replication to ensure linearizability. The cost is latency. Every write involves coordination across regions and replica groups, even when there’s no failure.

Note that PACELC is not a replacement for CAP. Instead, it tries to complete the picture and reminds architects that trade-offs don’t go away just because the system is healthy. Consistency and latency pull against each other even in the best-case scenario.

Latency vs Consistency

As mentioned, even in a normal operating mode, the system still faces a critical trade-off: should it return results quickly, or should it ensure those results reflect the most recent state across replicas?

In other words, a system must choose between low latency (L) and strong consistency (C).

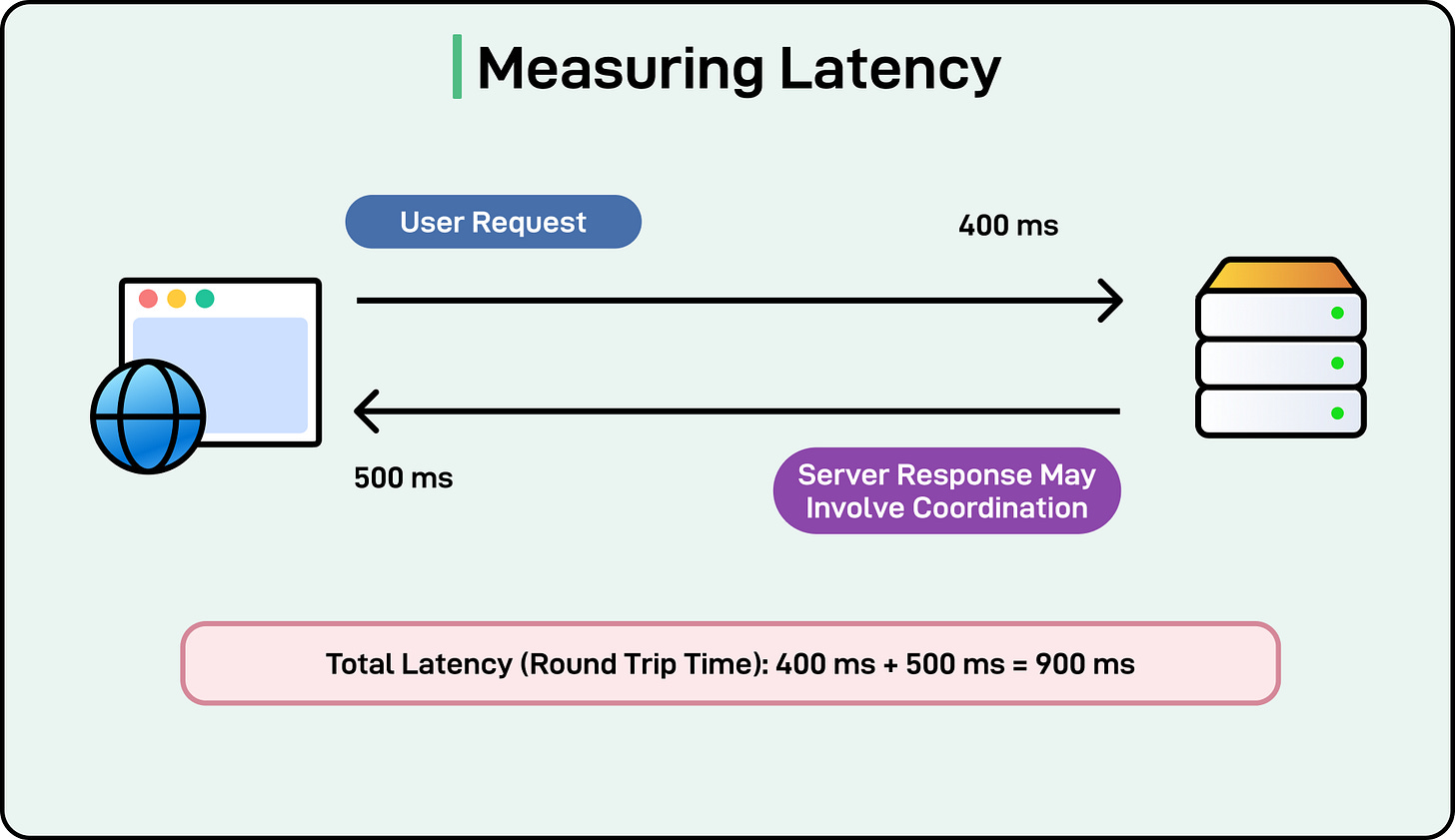

The trade-off comes from how systems synchronize state across replicas. Strong consistency requires coordination. That means waiting for a quorum of nodes to acknowledge a write before confirming success. It also means blocking reads until enough replicas agree on the latest version. These coordination steps add latency, not because of inefficient code, but because of the physics of distributed consensus.

Systems like Google Spanner go all in on consistency. Every write uses Paxos for consensus, and every replica agrees on commit order using tightly bound clocks provided by TrueTime. The result is globally consistent reads and writes, but with higher and more variable latencies. For use cases like financial transactions or distributed SQL workloads, this trade-off is acceptable.

See the diagram below:

On the other side, some systems allow tunable consistency. A developer can decide whether to wait for all replicas, a majority, or just one before confirming a read or write. Fewer acknowledgments mean faster responses. For example, a write with consistency level ONE will return as soon as the first replica stores it, regardless of whether others have seen it. This reduces latency but sacrifices consistency. A follow-up read may not see that write if it lands on a lagging replica.

This flexibility lets teams make context-aware decisions. A product recommendation engine might favor speed, accepting that a user could see a slightly outdated ranking. A payment processing service cannot afford such staleness. Showing a zero balance when money has already been deducted is unacceptable.

Designing for the right balance means understanding what latency guarantees the product needs. It means asking whether users care more about speed or correctness.

Designing Systems with CAP and PACELC

The real value of CAP and PACELC is in practical application. These models exist to help engineers make informed design choices under pressure.

It’s a good practice to start with the first question: What matters most for this system?

The answer shouldn’t be in abstract terms, but for the actual product, users, and use cases.

Is the data mission-critical or disposable?

Can the system afford a brief delay, or must it always be up?

Is it worse for users to see stale data or to wait a few seconds longer for the truth?

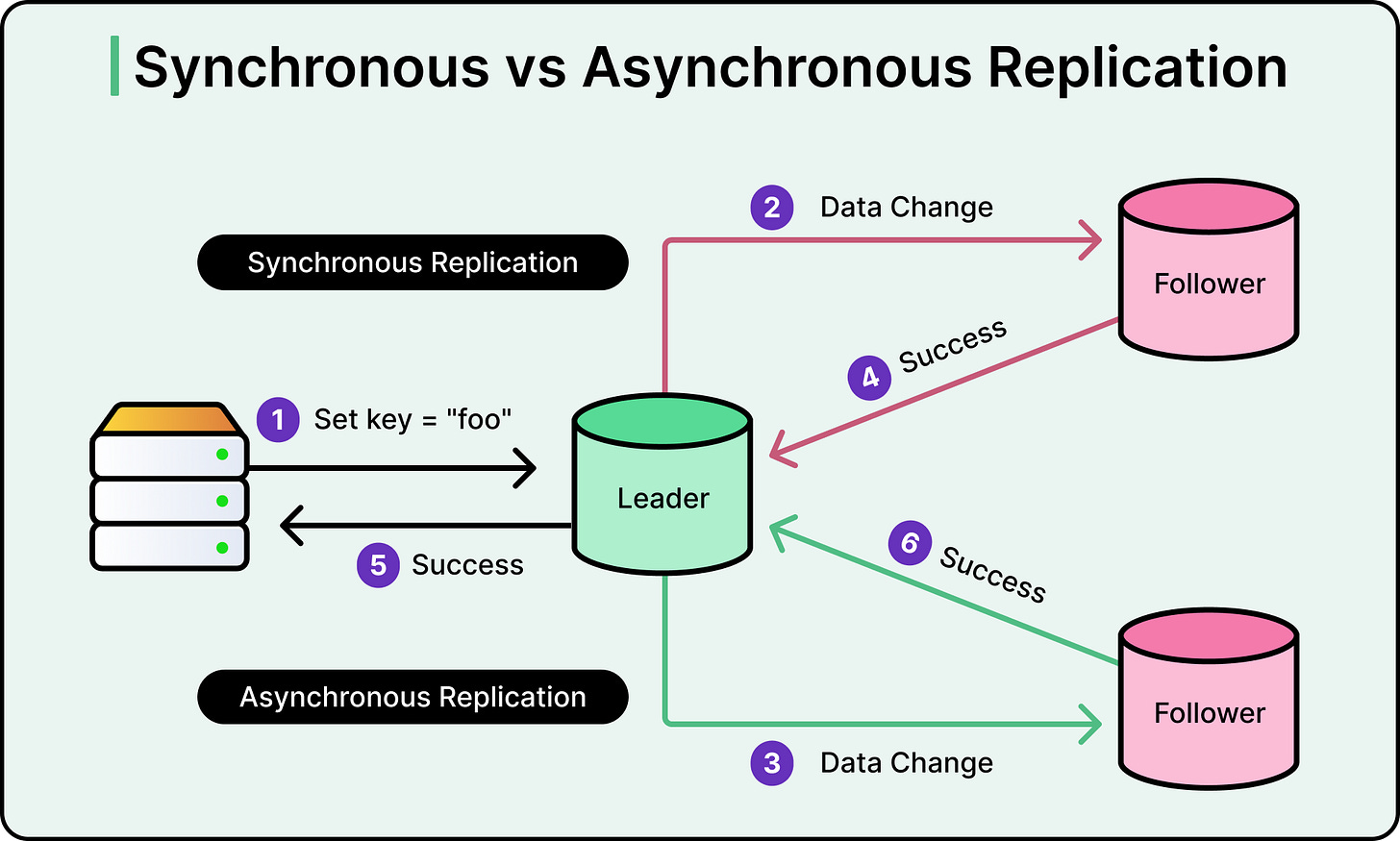

If consistency is non-negotiable, then availability and latency will take a hit during partitions or peak load. In this case, designing for quorum-based coordination and commit acknowledgments from multiple nodes can be useful. Tools like Paxos, Raft, or Multi-Paxos can help. Use write-ahead logs and synchronous replication to ensure no data is lost between replicas.

If availability is paramount, then allow writes to proceed in more relaxed conditions. It can be a good choice to use eventual consistency models and accept divergence for short periods.

When latency is the main concern, avoid synchronous coordination wherever possible. Techniques like local quorum reads, read-your-writes caching, and asynchronous replication help serve data fast, even if it may not be fresh.

See the diagram below for a comparison between synchronous and asynchronous replication.

Summary

In this article, we have taken a detailed look at consistency and partition tolerance in the context of the CAP and PACELC theorems.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Distributed systems must balance consistency, availability, and partition tolerance under real-world constraints, especially as they scale.

The CAP theorem states that during a network partition, a system must choose between consistency and availability.

Consistency means every read reflects the most recent successful write. Partition tolerance means the system keeps running despite network failures.

CAP trade-offs are not theoretical. They manifest as rejected writes, stale reads, or blocked operations during partitions.

CP systems prioritize correctness by rejecting operations when quorum is lost; AP systems favor uptime and reconcile later.

PACELC extends CAP by adding a second dimension: even without failure, systems trade latency for consistency.

Strong consistency requires coordination across replicas, which adds latency even when the system is healthy.

Choosing between consistency, availability, and latency depends on the product’s tolerance for stale data, downtime, and delay.

The most robust architectures don’t avoid trade-offs, but document them clearly and let teams decide based on real requirements.