Distributed database systems rely on coordination to work properly. When multiple nodes replicate data and process requests across regions or zones, a particular node has to take charge of write operations. This node is typically called the leader: a single node responsible for ordering updates, committing changes, and ensuring the system remains consistent even under failure.

Leader election exists to answer a simple but critical question: Which node is currently in charge?

The answer can’t rely on assumptions, static configs, or manual intervention. It has to hold up under real-world pressure with crashed processes, network delays, partitions, restarts, and unpredictable message loss.

When the leader fails, the system must detect it, agree on a replacement, and continue operating without corrupting data or processing the same request twice. This is a fault-tolerance and consensus problem, and it sits at the heart of distributed database design.

Leader-based architectures simplify the hard parts of distributed state management in the following ways:

They streamline write serialization across replicas.

They coordinate quorum writes so that a majority of nodes agree on each change.

They prevent conflicting operations from impacting each other in inconsistent ways.

They reduce the complexity of recovery when something inevitably goes wrong.

However, this simplicity on the surface relies on a robust election mechanism underneath. A database needs to be sure about who the leader is at any given time, that the leader is sufficiently up to date, and that a new leader can be chosen quickly and safely when necessary.

In this article, we will look at five major approaches to leader election, each with its assumptions, strengths, and trade-offs.

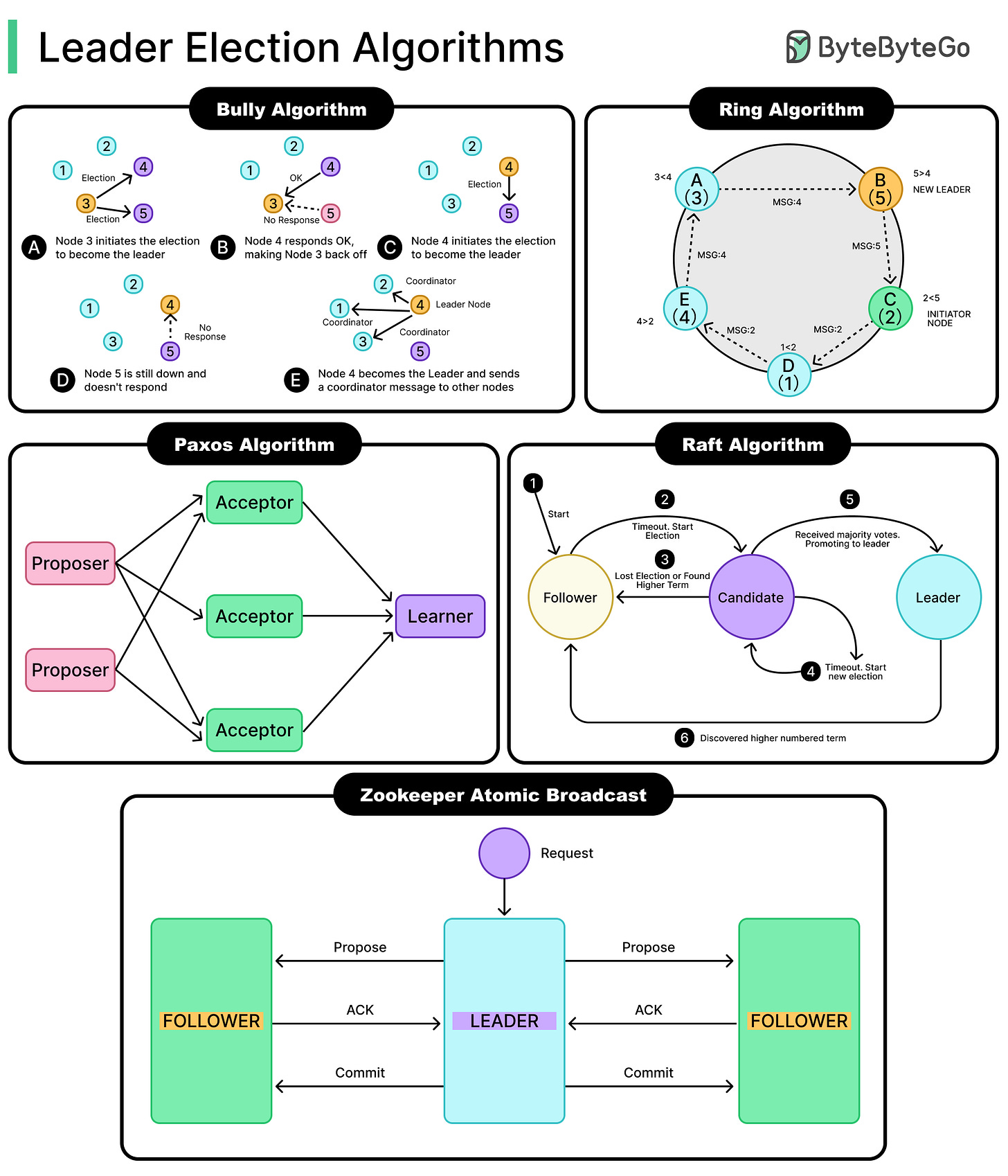

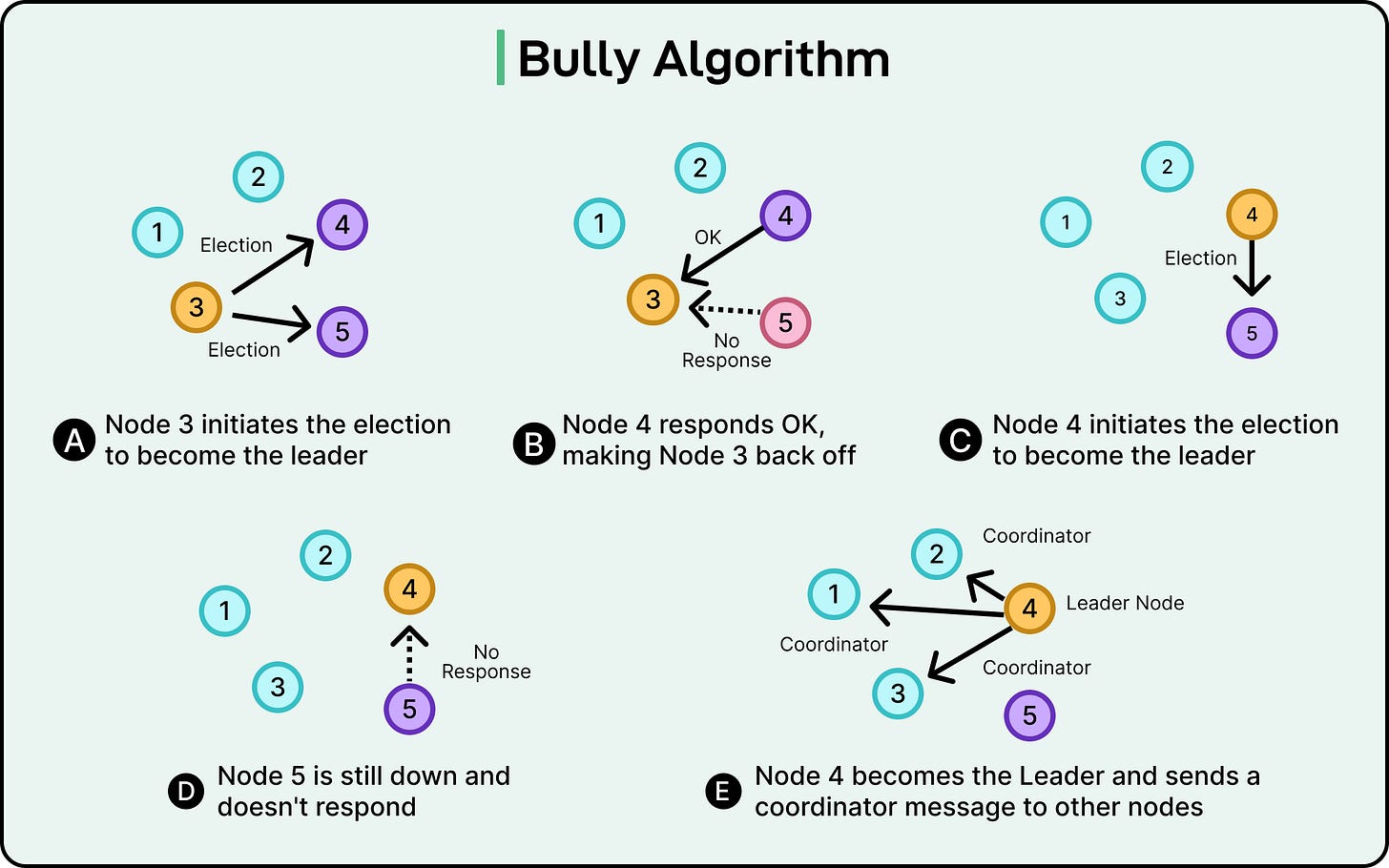

The Bully Algorithm

The Bully algorithm is one of the simplest methods for electing a leader in a distributed system. It relies on a basic rule: the node with the highest ID becomes the leader. If a node notices that the current leader is unresponsive, it tries to take over.

Each node in the system is assigned a unique numeric ID. The higher the ID, the higher the node’s “rank.” All nodes know each other’s IDs in advance, which is important for how the algorithm proceeds.

Suppose there are five nodes with IDs: 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Node 5 is currently the leader.

If Node 5 crashes, and Node 3 notices the failure (say, it stops receiving heartbeats), Node 3 initiates an election. It sends election messages to all nodes with higher IDs. In this example, these nodes are 4 and 5.

Here’s how such a process might work:

Node 3 detects that the leader node with ID 5 is down.

Node 3 sends election messages to 4 and 5.

Node 4 is alive and responds with OKs.

Node 3 backs off, seeing the response from a node with a higher ID.

Node 4 sends election messages to Node 5.

If Node 5 is down, Node 4 gets no reply.

Node 4 becomes the leader and broadcasts a COORDINATOR message to all the nodes.

See the diagram below:

Here’s what can happen:

If none of the higher-ID nodes respond (maybe they’re all down), node 2 declares itself the leader and sends a coordinator message to everyone else.

If any higher-ID node responds, that node takes over the election process. Node 2 backs off and waits, as we saw in the scenario.

Eventually, the node with the highest available ID (say node 4, if node 5 is still down) wins. It declares itself the leader and informs the rest.

The process stops once everyone knows who the new leader is.

If a lower-ID node initiates an election and multiple higher-ID nodes are alive, they may all respond with "OK" or "I’m alive" messages. However, these responses do not declare leadership. They only indicate:

"I have a higher ID than you. You’re not qualified to become a leader. I’ll take over the election process."

After sending the OK, each of those higher-ID nodes now starts its election, sending election messages to nodes with IDs even higher than theirs. This process cascades upward.

The Bully algorithm makes a few strong assumptions:

All nodes know each other's IDs.

Nodes communicate over reliable links.

Leader failure can be detected accurately.

The biggest problem with the Bully algorithm is the communication cost. Every election can involve a burst of messages between multiple nodes. In a large cluster, this gets expensive fast.

It also has poor partition tolerance. If a node falsely assumes the leader is dead due to network delay, it can start an unnecessary election, leading to confusion or duplicated leadership messages.

There’s also the issue of staggered recovery. If nodes come back online out of order, each new node with a higher ID may trigger a new election. The system spends more time electing leaders than doing actual work.

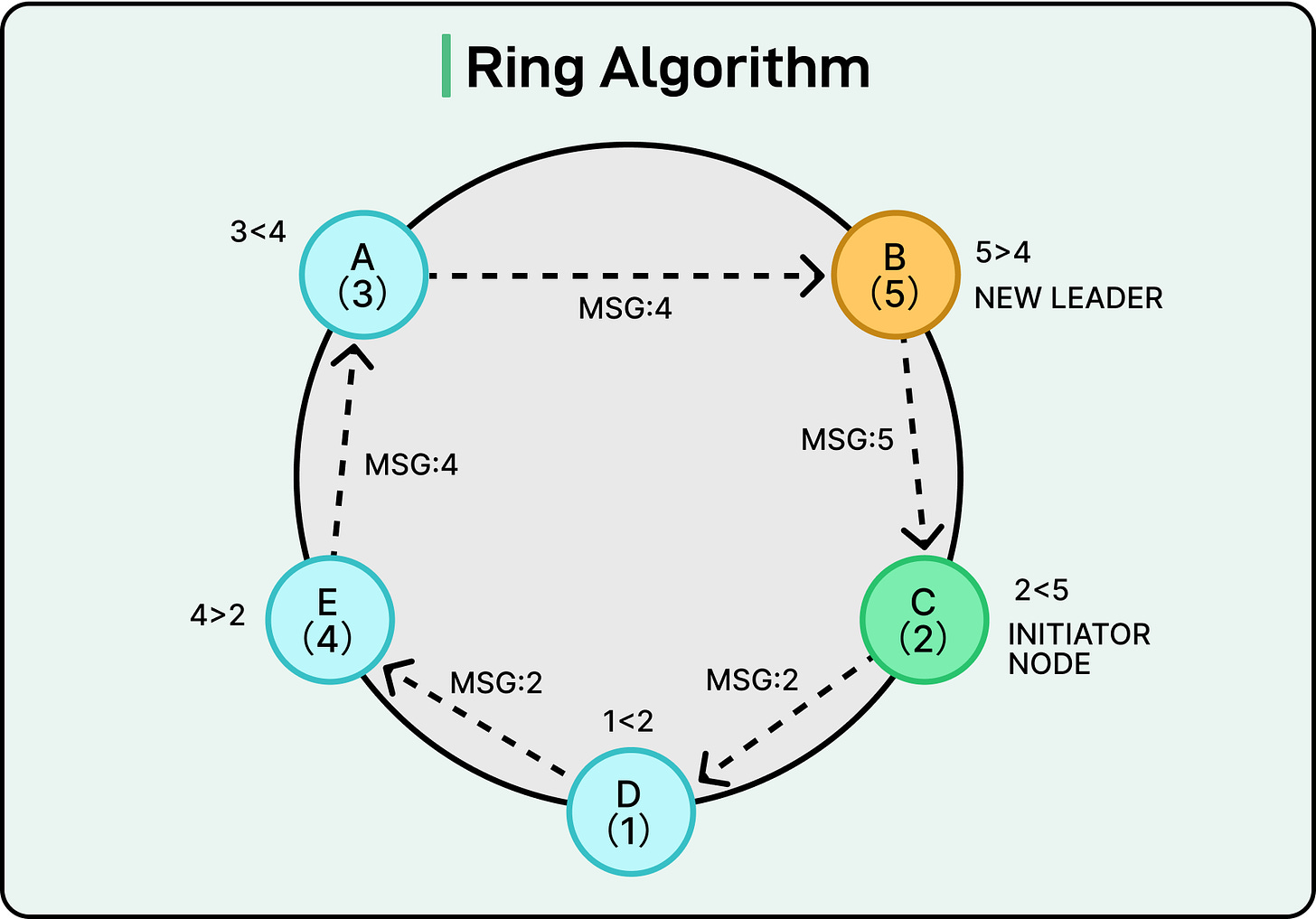

The Ring Algorithm

The Ring algorithm approaches leader election with one simple rule: pass a message around the circle, and the node with the highest ID wins. Unlike the Bully algorithm, there’s no concept of interruption or priority escalation. Every node gets a chance to participate, but only one is crowned as the leader.

The system assumes a logical ring topology, where each node knows who comes next. Messages are passed one hop at a time, always in the same direction. Also, each node has a unique numeric ID.

Suppose there are five nodes arranged in a ring with IDs: Node A (3), Node B (5), Node C (2), Node D (1), Node E (4), back to Node A.

If Node C detects that the leader is down, it starts an election by sending a message to its neighbor (Node D). The message contains its ID of 2. Here’s what can happen:

Node D (1) receives ID 2, compares it to its ID (1), and forwards 2 to Node E.

Node E (4) sees that 4 > 2, so it replaces the message content with 4 and forwards it. There is also a variant of the algorithm in which the ID is not replaced but appended. So the message may become [2,4], but we will go with the replacement approach for this example.

Node A (3) sees that 4 > 3, so it keeps 4 and forwards.

Node B (5) replaces it again with 5 and forwards.

Eventually, the message returns to Node C, the originator.

At this point, Node C sees that its message has returned with the ID 5, which is the highest one in the system. Therefore, it concludes that Node B (ID 5) should be the leader. It sends a coordinator message around the ring, informing everyone that Node B is now the leader.

Here’s why the ring algorithm works:

The ring ensures that every live node participates in the election.

The highest ID naturally propagates and replaces lower IDs as the message circulates.

The originator detects when the cycle completes and finalizes the decision.

Only one leader is elected, and no two nodes can simultaneously claim leadership. The process is guaranteed to terminate as long as the ring is intact and all links function.

There are some weaknesses to this approach:

It assumes reliable, ordered delivery. If a message is lost or delayed, the entire election process can stall.

Breaks under dynamic topology. If nodes come and go, the ring must be rebuilt. That’s slow and error-prone.

Election latency grows linearly with the number of nodes. It always takes N hops to return to the originator, even if the winner is obvious early on.

The Paxos Algorithm

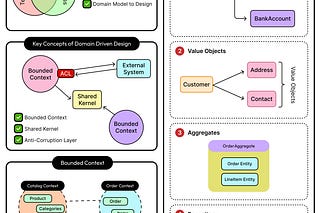

Unlike algorithms that explicitly say “this node is now the boss,” Paxos lets any node try to propose a value, then uses quorum voting to decide which proposal gets accepted. Leadership emerges from whichever node consistently succeeds at this game.

It’s a powerful protocol, but also tricky to get right. Paxos is safe even under unreliable networks, message delays, and partial failures. But it demands precise logic, persistent storage, and a solid understanding of quorum dynamics.

At its core, Paxos tries to solve the problem of consensus or how to get a group of nodes to agree on a single value, even if some of them crash or messages arrive out of order. This value could be anything, such as a log entry, a config setting, or a leader node.

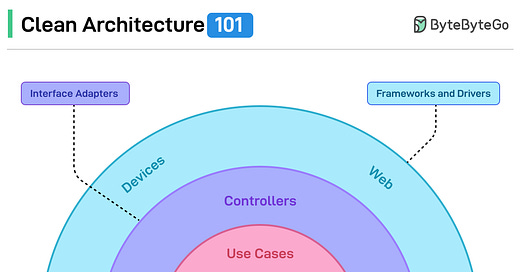

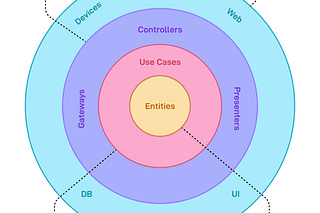

Paxos splits the process into two phases:

Prepare/Promise

Propose/Accept

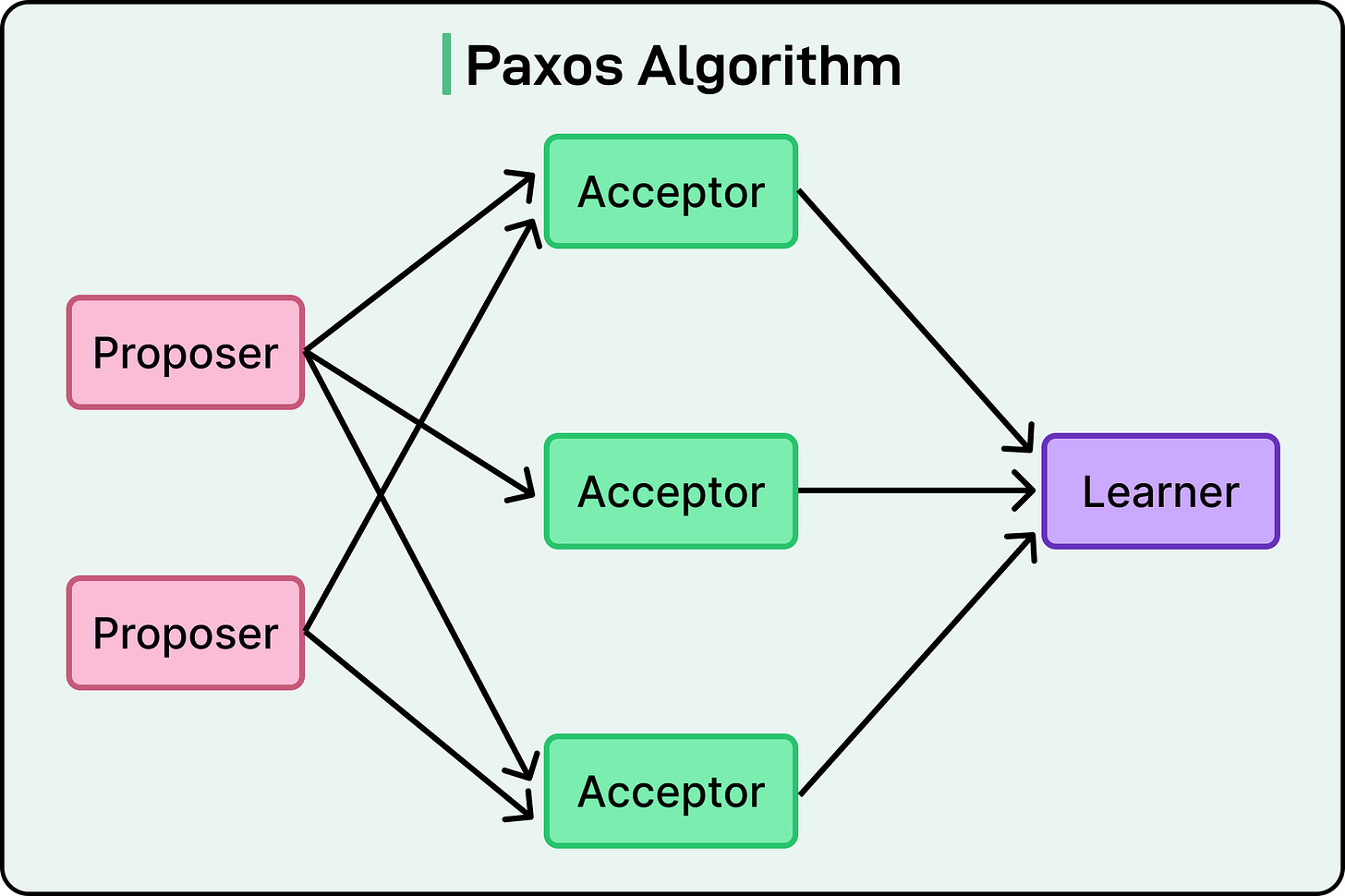

Each node plays one or more roles: proposer, acceptor, and sometimes learner. See the diagram below:

Let’s walk through the process using leader election as the value being proposed.

Phase 1: Prepare and Promise

Any node can act as a proposer. To start, it generates a proposal number, which is a monotonically increasing ID (often a combination of logical counter and node ID for uniqueness).

The proposer sends a Prepare(n) message to a majority of acceptors, asking them to promise not to accept proposals numbered less than n.

When an acceptor receives a Prepare(n), it responds with a Promise(n) if it hasn’t already promised something higher. Along with the promise, it includes the highest proposal it has already accepted, if any.

This step helps suppress conflicting or stale proposals. It ensures future proposals are either newer or build on prior accepted ones.

Here’s an example:

Proposer A sends Prepare(100)

Acceptors 1, 2, and 3 receive it and reply:

Acceptor 1: Promise(100), no prior accepted value

Acceptor 2: Promise(100), previously accepted value (leader = Node 4)

Acceptor 3: Promise(100), no prior accepted value

Now A knows it must carry forward “Node 4” as the leader candidate, even if it didn’t come up with it originally.

Phase 2: Propose and Accept

The proposer selects a value:

If any acceptor replied with a prior accepted value, the proposer must re-propose that value.

If none were accepted before, it can choose its own (for example, “elect Node A as leader”).

It sends an Accept(n, value) message to the same majority. If acceptors haven’t promised anything higher in the meantime, they respond with Accepted(n, value). Once a quorum accepts the value, it is chosen.

Multi-Paxos

In the basic Paxos protocol, every value requires a new round of Prepare/Promise and Accept/Accepted steps. That’s expensive and inefficient if values are proposed frequently, like in a replicated log.

Multi-Paxos optimizes this by:

Electing a distinguished proposer to act as the stable leader.

Letting the leader skip phase 1 for subsequent values, reusing the leadership as long as no one challenges it.

This creates a form of stable leadership. The leader is not elected through a separate mechanism but rather emerges as the only node consistently succeeding in proposing values.

Why Paxos is Hard

Paxos can be hard to implement correctly for the following reasons:

Proposal numbers must be unique and ordered globally.

Nodes must persist state (promises, accepted values) across restarts

Recovery from partial failures or leadership handoff requires careful coordination

It also lacks a clear leadership model in the base version, which leads many teams to either:

Use Multi-Paxos with a stable coordinator

Switch to Raft, which offers the same safety with a more understandable election process

Raft Algorithm

Raft exists because Paxos, while powerful, is hard to implement and even harder to reason about. Raft delivers the same safety guarantees as Paxos, such as no two leaders at the same time, agreement on the log, and progress if a majority is up. However, the design is easier to follow, debug, and deploy.

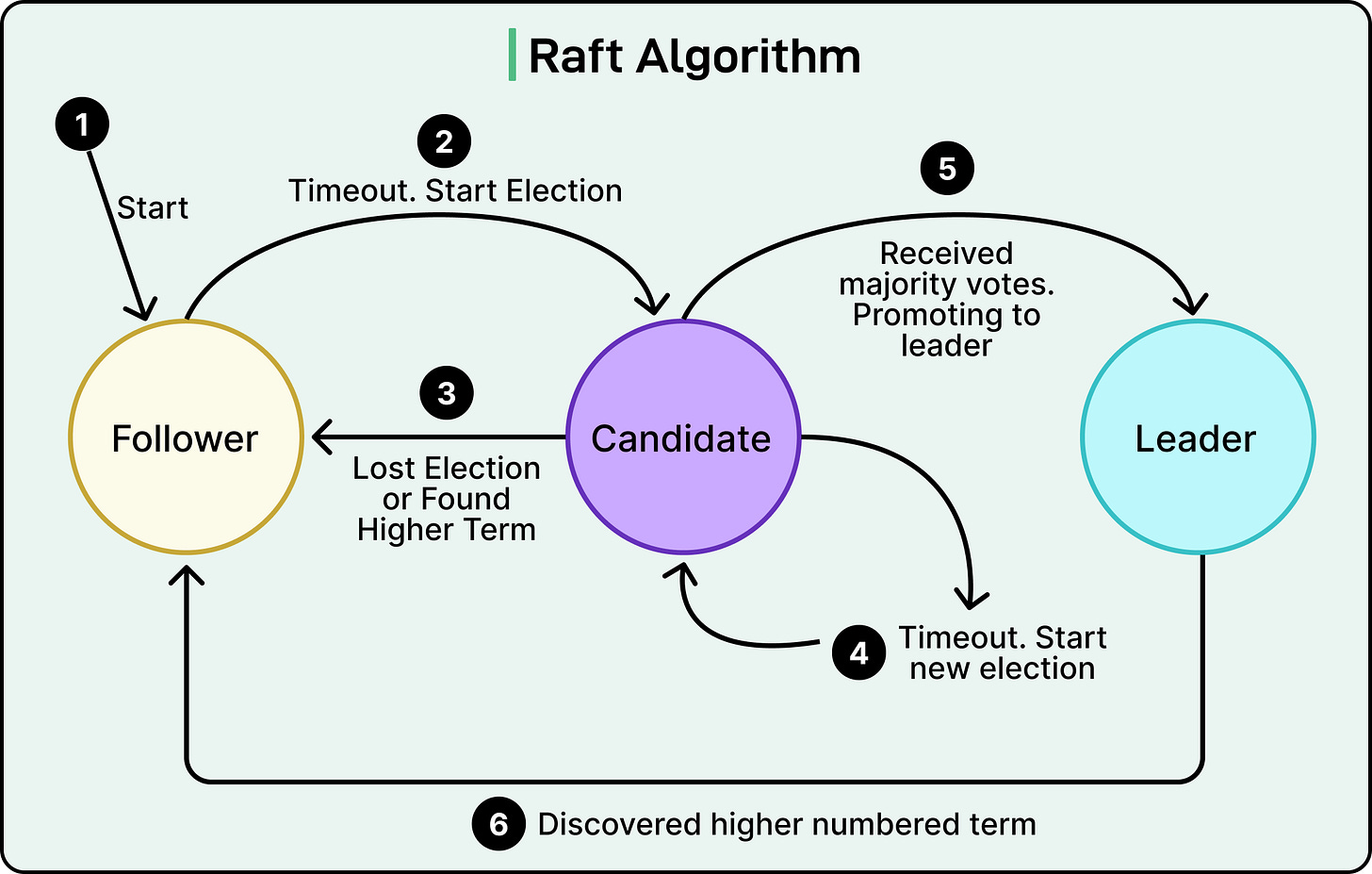

Each Raft node exists in one of three states:

Follower: Passive node, listens to the leader and responds to requests.

Candidate: Attempts to become the leader when no heartbeats are received.

Leader: The active node that handles all client requests and replication.

Nodes start as followers. If they go too long without hearing from a leader (via heartbeats), they assume the leader is dead and trigger an election.

See the diagram below that shows the possible states of the nodes.

Raft avoids election conflicts by using randomized timeouts. Each follower starts a countdown with a random value between, say, 150–300 milliseconds. If it doesn’t hear from a leader before the timer expires, it becomes a candidate and starts an election.

The candidate:

Increments its term (a kind of epoch counter).

Votes for itself.

Sends RequestVote RPCs to all other nodes.

Other nodes will vote for the candidate only if:

They haven’t voted in the current term.

The candidate’s log is at least as up-to-date as their own.

If the candidate gets votes from a majority, it becomes the new leader and begins sending heartbeats to maintain authority. If no candidate wins (for example, split vote), everyone waits and tries again with new timeouts. This randomized approach ensures that one node eventually gets ahead of the pack.

Raft uses terms to track leadership epochs. Each log entry is tied to the term in which it was created. This makes it easy to detect and reject stale or conflicting leaders. Before voting, nodes compare logs. A candidate with an outdated log will be rejected, even if it reaches other nodes first. This ensures that only the most up-to-date node can become the leader. Leaders then replicate new log entries to followers using AppendEntries RPCs. Once a quorum has acknowledged an entry, it’s considered committed.

Raft solves the split-brain problem by enforcing quorum rules:

A leader must have support from a majority of nodes.

Two leaders can't be active in the same term.

A follower only accepts requests from the leader of the current term.

If a stale leader tries to act after a network partition, it’s immediately rejected by newer-term followers.

This clear structure avoids the ambiguity seen in protocols like basic Paxos, where concurrent proposers can slow each other down or leave systems in limbo.

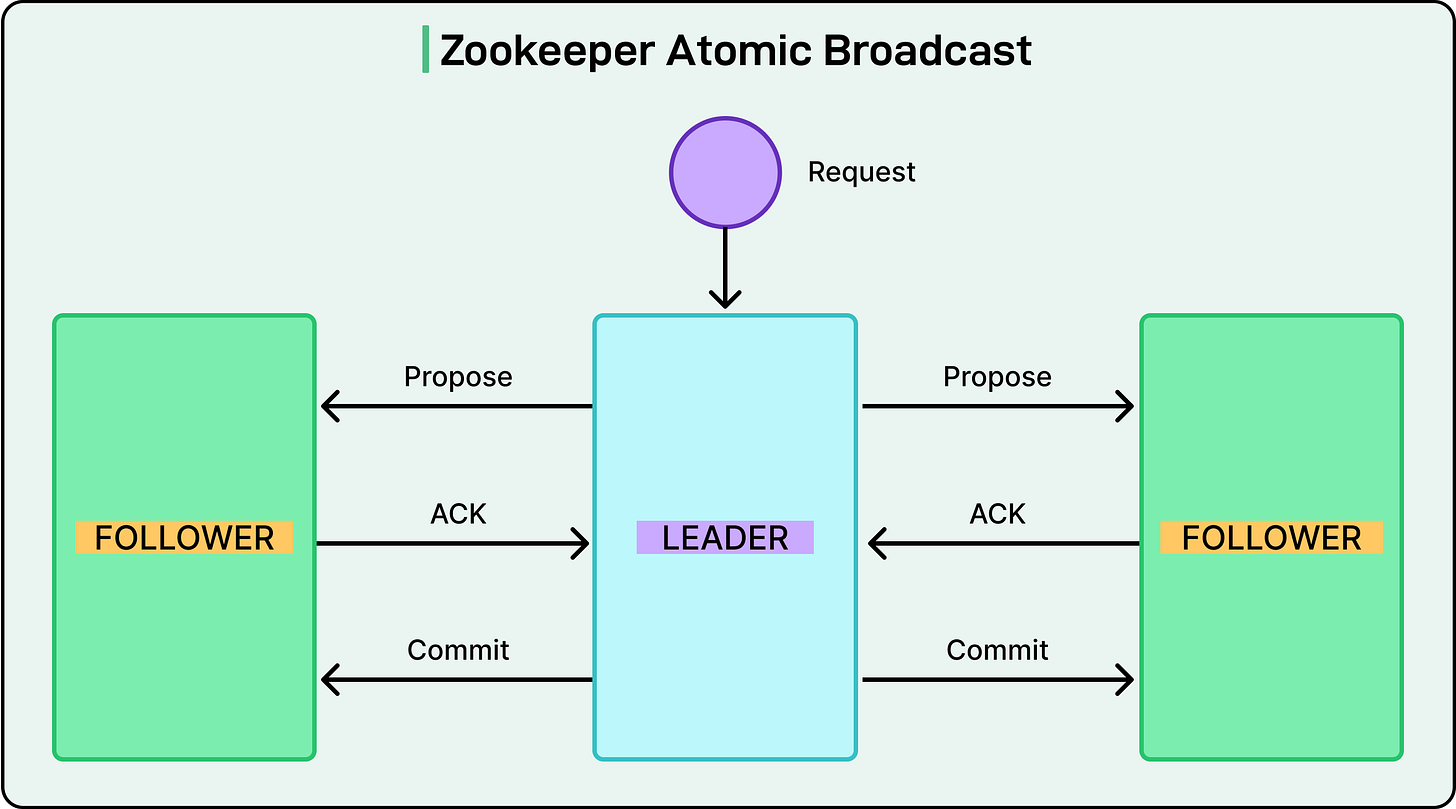

Zookeeper and Zab

ZooKeeper isn’t a database. It doesn’t store user records, query indexes, or replicate log entries. Instead, it plays a critical role in the distributed ecosystem: coordination. When systems need to elect a broker, manage leader failover, or synchronize configuration, ZooKeeper is the go-to service.

Internally, ZooKeeper uses its protocol called Zab (ZooKeeper Atomic Broadcast). Zab handles both leader election and state replication, ensuring that even coordination metadata is safe, consistent, and fault-tolerant.

See the diagram below that shows Zookeeper Atomic Broadcast.

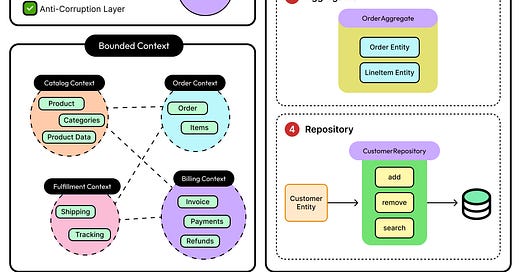

ZooKeeper exposes a hierarchical namespace through znodes. These znodes can hold data and metadata, and can be either persistent or ephemeral.

Ephemeral znodes disappear when the client that created them disconnects.

Sequential znodes get a monotonically increasing number appended to their name.

Zab ensures that ZooKeeper’s leader election is robust. Before a new leader can start processing write requests, it must synchronize with a quorum of followers to ensure it has the most recent committed state.

Each transaction in ZooKeeper is tagged with a zxid (ZooKeeper Transaction ID), which combines the leader's epoch and the log index. This allows nodes to determine who has the freshest view of the world.

During the leader election in Zab:

The candidate with the most up-to-date ZXID is preferred.

The new leader must perform a state synchronization phase with a quorum before it can commit new transactions.

If it can’t sync safely, the election fails and retries.

Comparative Analysis

Each of the five leader election algorithms covered solves the same fundamental problem: selecting a single, reliable leader in a distributed system. However, they approach it with different assumptions, trade-offs, and operational characteristics.

Here are a few points to keep in mind:

In terms of the leadership model, Bully and Ring use deterministic rules based on node IDs. Paxos, Raft, and Zab use quorum-based decision making.

For failure tolerance, Bully assumes reliable links and accurate failure detection. A node falsely marked as dead can lead to multiple leaders or frequent re-elections. The Ring algorithm stalls if any node in the ring crashes without notice. By contrast, Paxos, Raft, and Zab all tolerate partial failures and still reach safe decisions.

In terms of performance, Raft and ZooKeeper/Zab handle re-elections predictably. Bully and Ring suffer in high-churn environments. Paxos, especially in its raw form, can flounder with multiple proposers and unclear leadership, unless paired with enhancements like Multi-Paxos.

Regarding implementation ease, Bully and Ring are straightforward to implement. Raft is more work, but manageable. Paxos is quite difficult to get right. ZooKeeper/Zab hides complexity behind an API, but the underlying mechanics aren’t trivial.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at leader election algorithms for distributed databases in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Leader election ensures that distributed databases can safely coordinate writes, maintain consistency, and recover from failures without ambiguity or data loss.

The Bully algorithm uses unique numeric IDs where the highest-ID node eventually becomes the leader. It’s simple but fragile, assuming reliable communication and static membership.

The Ring algorithm arranges nodes in a logical ring. A node circulates its ID, and each participant forwards the highest one it has seen. When the message returns to the originator, the highest-ID node is declared the leader. It’s lightweight but brittle under node failures or topology changes.

Paxos is a quorum-based consensus algorithm where leadership emerges indirectly. Any node can propose a value. The one that consistently gathers a quorum wins. It uses a two-phase protocol (Prepare/Promise and Propose/Accept) to ensure safety.

Multi-Paxos adds stability by letting one node act as the long-term leader, reusing its role for multiple proposals. This avoids repeated elections but adds complexity and requires durable state management.

Raft was designed for clarity. It explicitly defines leader election via RequestVote RPCs, randomized timeouts, and term-based coordination. Only one leader is active at a time, and it must gather a quorum of votes.

ZooKeeper, powered by the Zab protocol, provides external coordination services rather than internal consensus. It elects leaders using ephemeral sequential znodes. The node with the lowest znode becomes the leader, and others monitor their predecessor.