Scalability is the ability of a system to handle growth (more users, more data, and more requests) with high performance. In modern distributed systems, scalability is not a nice-to-have. Whether serving a global user base or responding to a viral spike, systems that fail to scale often fail outright.

This becomes especially critical in cloud-native environments, where usage patterns shift rapidly and infrastructure costs scale with traffic. An application that handles 1000 users today might need to serve 100K tomorrow if things work out. If that jump requires a complete redesign, it’s already too late.

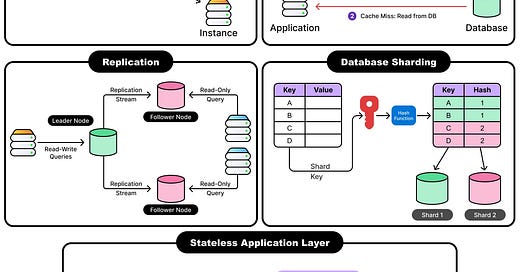

Scalability is often confused with performance or elasticity. These are related but distinct concerns:

Performance is related to how fast a system responds under a fixed load. It’s a question of latency and throughput.

Elasticity is related to how quickly and automatically a system adapts to changing demand, often in terms of infrastructure.

Scalability is related to how well a system maintains its characteristics as load increases. It asks: What happens when the load doubles?

In this article, we look at core strategies that are used to build scalable systems. Each technique solves a different problem, and most systems use a combination of them. Getting scalability right isn’t about choosing one pattern, but about knowing when to apply which tool, and where it might cause problems.

Horizontal vs Vertical Scalability

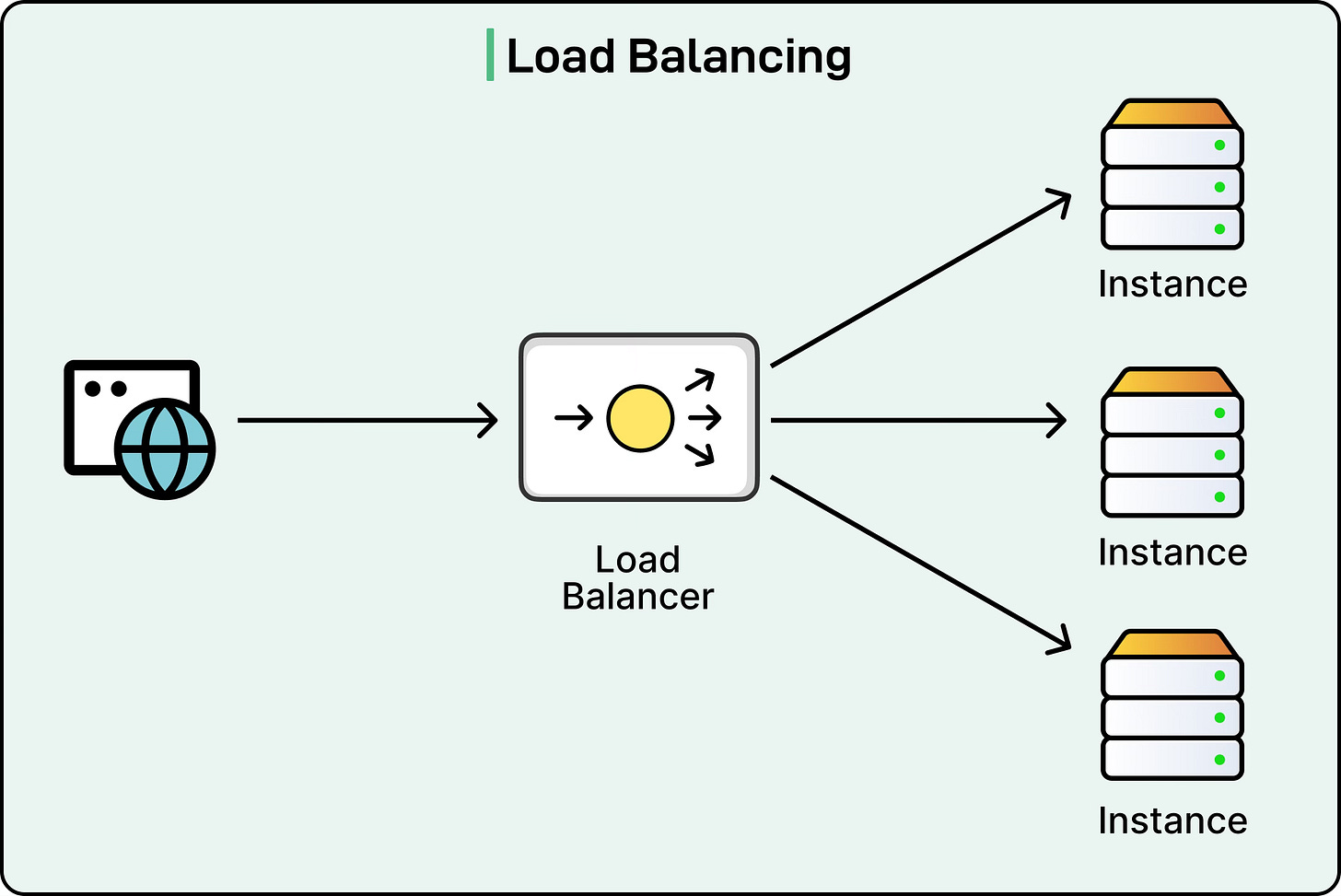

There are two primary ways to scale a system: scale up or scale out.

Vertical scaling, or scaling up, means increasing the resources available to a single machine. Add more CPU, more RAM, faster disks. The application stays the same, but the machine it runs on gets stronger. This works well for monoliths or legacy systems that aren’t designed to run in parallel.

It’s simple, often just a matter of choosing a bigger EC2 instance or a beefier VM. However, vertical scaling hits limits quickly. Hardware has practical ceilings. CPUs reach saturation points, memory upgrades become disproportionately expensive, and disk I/O starts to drag. More importantly, vertical scaling concentrates risk. When everything runs on a single node, that node becomes a single point of failure. A hardware crash can bring down the entire service.

Horizontal scaling, or scaling out, distributes the load across multiple machines. Instead of relying on one powerful server, the system spreads work across a fleet of nodes. Adding capacity means adding more instances, not upgrading existing ones. This model underpins most modern distributed systems and cloud-native architectures.

Horizontal scaling brings advantages:

Fault tolerance: Losing one node doesn’t take the whole system down.

Cost control: It’s often cheaper to run several modest machines than one massive one.

Flexibility: New nodes can be added dynamically as demand grows.

That flexibility comes with trade-offs. Services must be stateless or designed to externalize state. Load balancing becomes essential. Distributed coordination, data consistency, and deployment complexity all increase. In other words, horizontal scalability shifts the challenge from infrastructure to architecture.

Early-stage systems often begin with vertical scaling for simplicity. However, as traffic grows and reliability becomes critical, horizontal scaling provides the resilience needed to support long-term growth.

Stateless vs Stateful Components

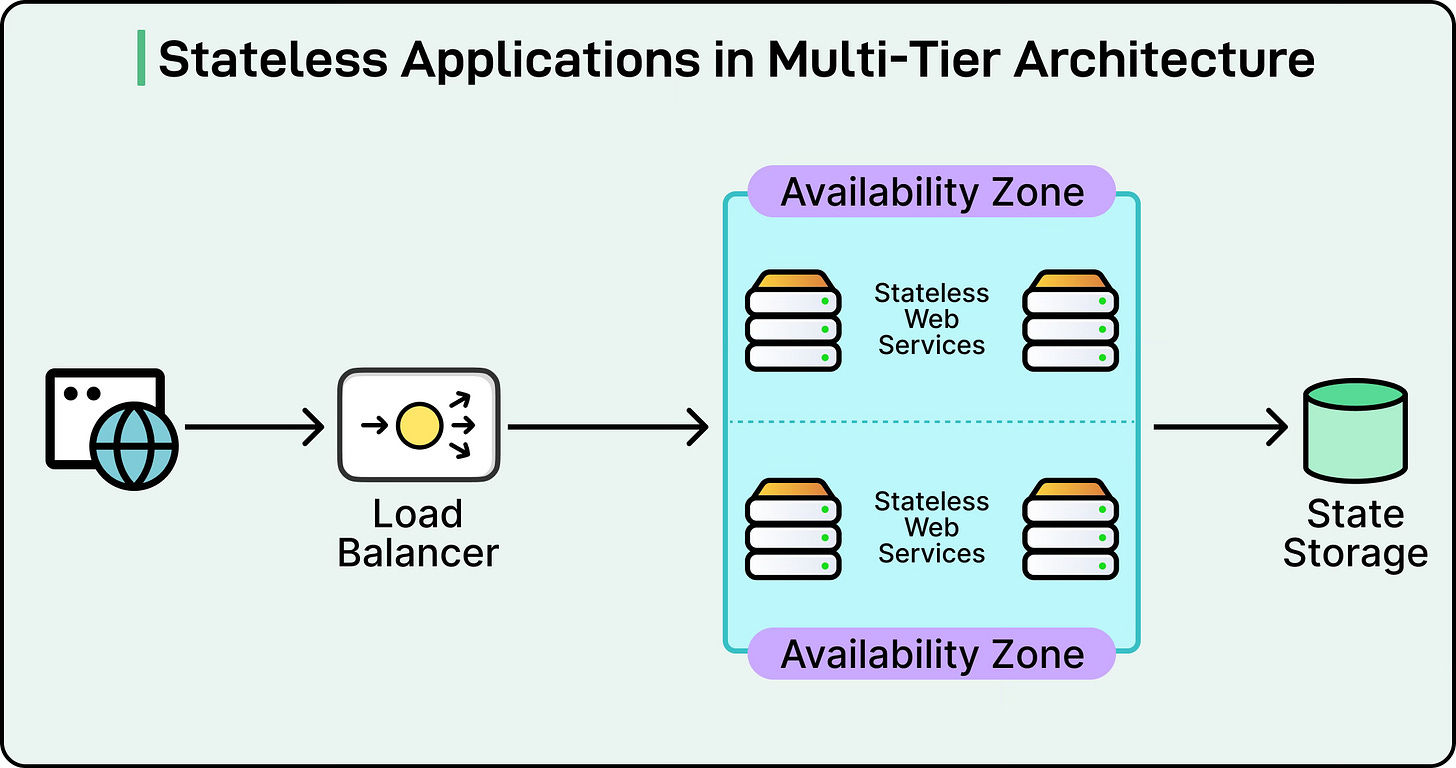

Scalability depends heavily on how a system handles state. At the core of most distributed architectures lies an important question: Should this component remember anything?

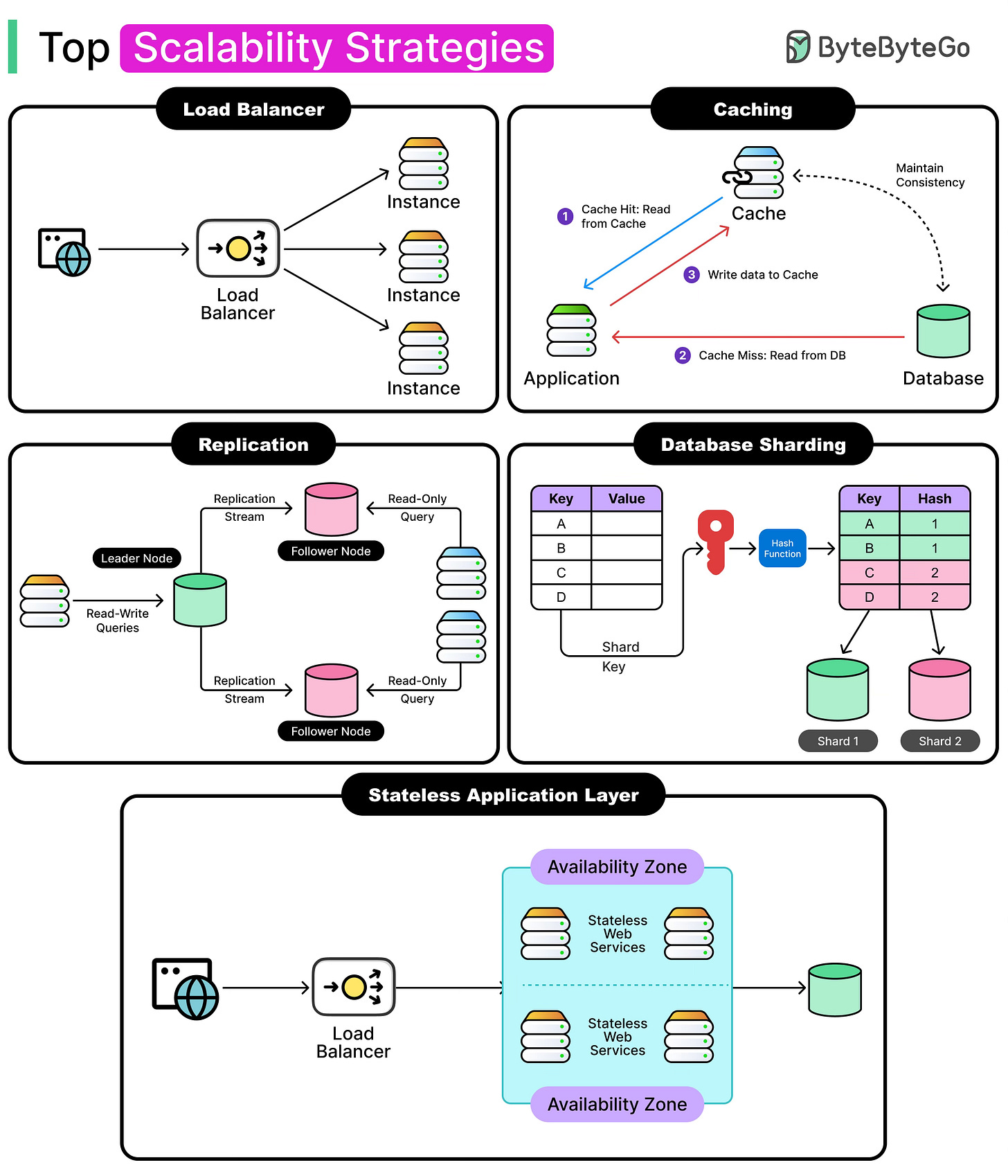

Stateless components don’t retain any information about previous interactions. Each request is independent. The server doesn’t know what came before. Most REST APIs follow this pattern. A request arrives, gets processed, and the response goes back. See the diagram below:

This stateless model simplifies scaling. Instances can be cloned and distributed behind a load balancer with minimal coordination. If one instance goes down, another can handle the next request.

Stateful components, by contrast, maintain context across sessions or requests. They store data in memory, track ongoing connections, or hold session-specific information. Examples include:

Databases that persist user or system data.

WebSocket servers manage live bi-directional connections.

In-memory caches like Redis with real-time application state.

Application servers that manage user sessions locally.

These components introduce complexity. Scaling them horizontally requires careful handling of data and coordination. Simply spinning up more instances doesn’t work unless the state is shared, replicated, or partitioned correctly.

To make stateful systems scale, a couple of common approaches are as follows:

External session stores: Offload session state to a database or cache like Redis, so stateless services can still support logged-in users.

Sticky sessions: Route the same user to the same server to preserve in-memory session state. This approach can work temporarily, but it creates fragility and poor fault tolerance.

It’s tempting to believe that the state is inherently bad, but every real system has it somewhere. The challenge lies in where it lives and how it's managed. Stateless design makes scalability easier, but all meaningful systems eventually deal with state, so it must be handled with intention.

Auto Scaling Techniques

Manual scaling doesn’t work when traffic patterns shift, usage spikes come without warning, and fixed infrastructure either breaks under pressure or burns money during idle time. Auto-scaling solves this by reacting to real-time metrics and adjusting system capacity without human intervention.

Modern platforms support automated scaling in multiple ways, but two of the most common ecosystems (for example, Kubernetes and AWS) offer mature, production-grade solutions tailored to different kinds of infrastructure. Let’s look at them in a little more detail for reference:

1 - Kubernetes Pod Autoscaling

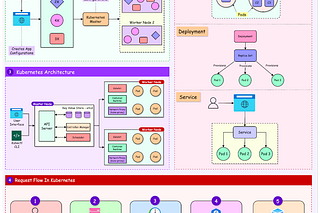

Kubernetes treats scaling as a core capability. It supports several auto-scaling mechanisms, each targeting a different part of the system.

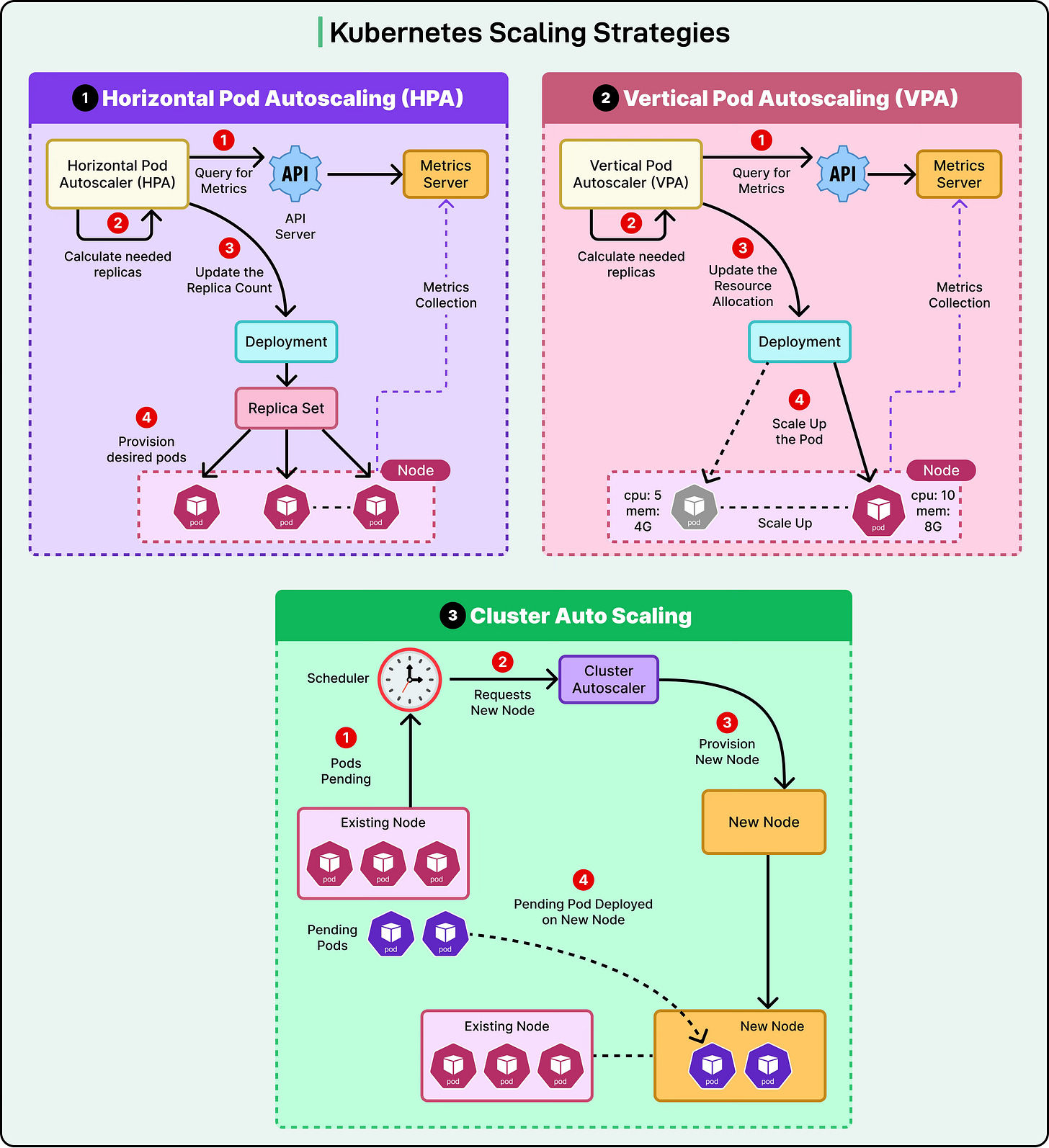

Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA) increases or decreases the number of pod replicas based on metrics like CPU, memory usage, or custom-defined metrics.

Vertical Pod Autoscaler (VPA) adjusts the resource requests and limits for individual pods. If a pod consistently needs more memory than it requests, VPA recommends or applies new values. This helps right-size workloads, but comes with trade-offs. VPA may restart pods to apply changes, which can affect availability.

Cluster Autoscaler watches for pods that can't be scheduled due to insufficient resources. When this happens, it scales out the underlying node pool. If excess capacity is detected, it can scale nodes back to save cost.

See the diagram below that shows these auto-scaling strategies in the context of Kubernetes:

In practice, these autoscalers often work together. For example, when a backend API service receives sudden spikes in traffic, HPA adds more pods to handle the load. If the node pool runs out of room to place these pods, the Cluster Autoscaler steps in and provisions additional nodes.

2 - AWS Auto-Scaling

AWS offers auto-scaling across a wide range of services, each with its own operational model.

EC2 Auto Scaling Groups let engineers define a group of instances tied to scaling policies. Based on CPU usage, request latency, or custom CloudWatch metrics, the group scales up or down. Launch configurations or launch templates define how new instances get initialized.

ECS (Elastic Container Service) supports auto-scaling tasks based on service demand, integrating with Application Load Balancers and CloudWatch alarms.

RDS (Relational Database Service) supports storage auto-scaling and, in some configurations, read replica promotion for scaling read-heavy workloads.

Scaling in AWS revolves around CloudWatch alarms, scaling policies, and lifecycle hooks. Alarms monitor defined metrics. When thresholds are breached, scaling policies are triggered. Lifecycle hooks can pause instance termination or launch, giving time to run cleanup scripts, drain connections, or register new nodes.

Sharding and Replication

Scaling stateless services is relatively straightforward.

The hard part begins when data gets involved. Databases, message queues, and persistent stores are inherently stateful, and they don’t scale as easily as web servers or API gateways. This is where sharding and replication come into play. They are two foundational strategies for scaling stateful systems.

Sharding

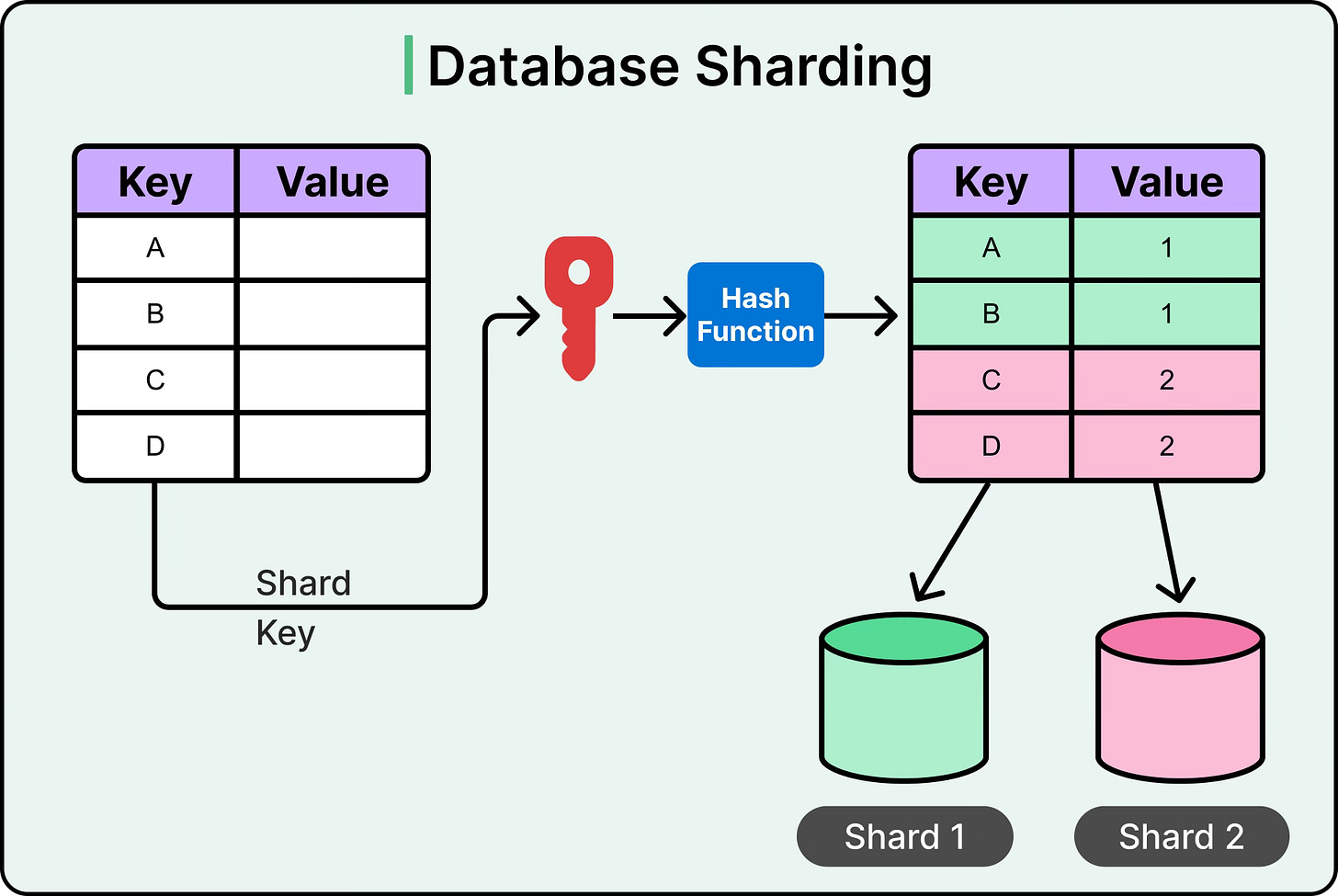

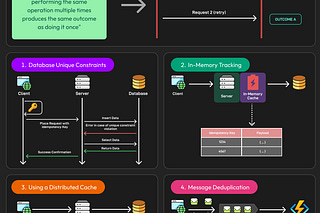

Sharding distributes data across multiple partitions, called shards, where each shard handles a subset of the overall dataset. The goal is to split the load so that no single machine becomes a bottleneck. Instead of one massive table handling every user, each shard might handle a specific slice, based on user ID, region, or hashed keys.

This enables horizontal scalability for databases. Writes, reads, and queries can run in parallel, targeting only the shard that owns the relevant data. It also improves fault isolation. If one shard goes down, only a subset of users is affected.

Common sharding strategies include:

Range-based sharding: Data is divided by value ranges, like user_id 1–10000, 10001–20000, and so on. It’s simple but prone to hotspots if access patterns skew toward specific ranges.

Hash-based sharding: A hash function distributes records more evenly across shards, reducing hotspots but complicating range queries.

Directory-based sharding: A lookup table maps keys to shards. It adds flexibility but introduces a central dependency.

See the diagram below for an example of database sharding using hash-based approach.

Replication

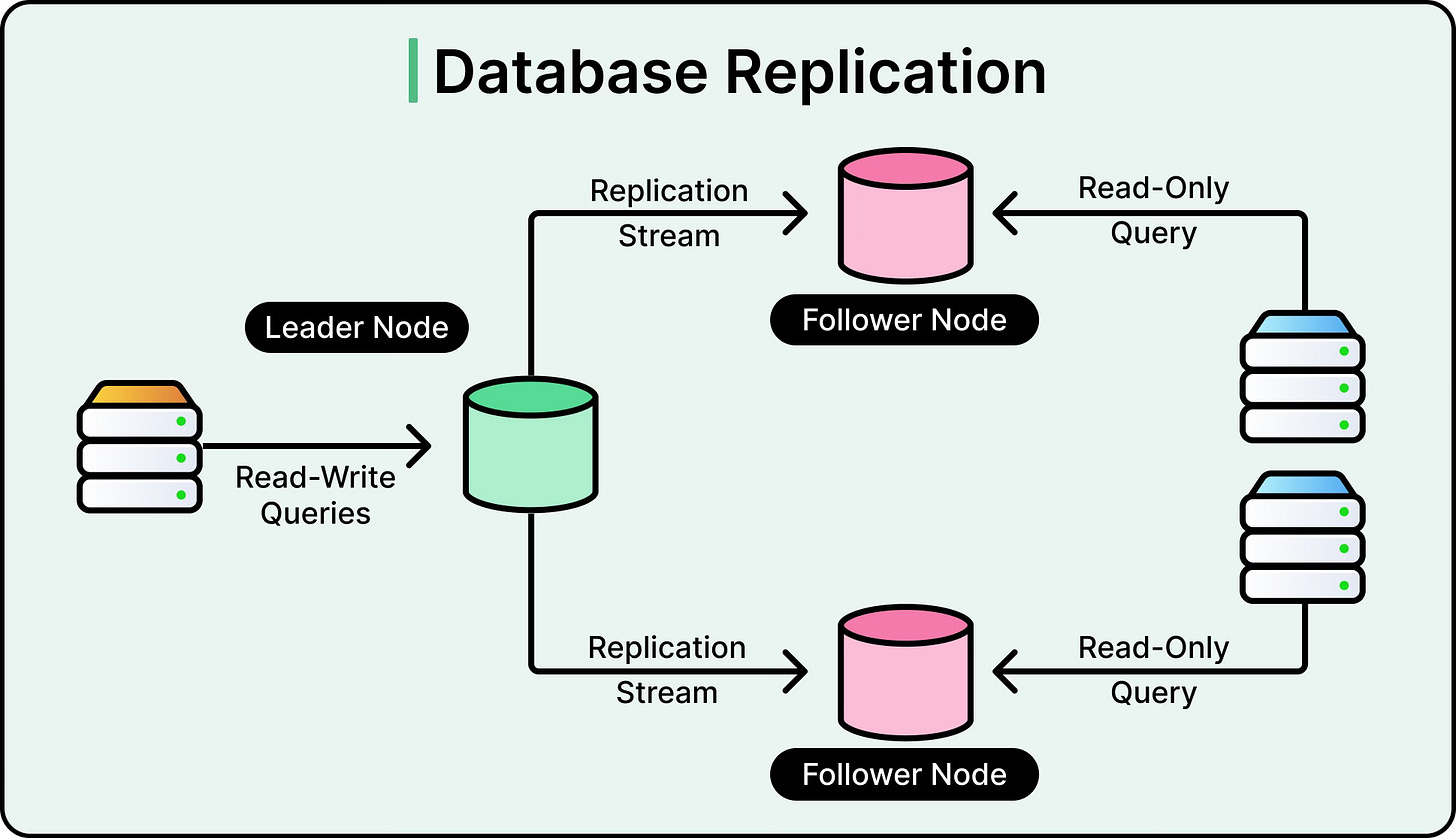

While sharding splits data to scale writes and storage, replication copies data to improve reads and availability.

In primary-secondary setups, the primary node handles all writes, and one or more replicas handle reads. This reduces load on the primary and allows read-heavy systems to scale horizontally. Replication also serves as a failover mechanism. If the primary fails, a replica can be promoted. See the diagram below:

Some databases support multi-leader replication, where multiple nodes accept writes and sync with each other. This improves write throughput and geographic distribution, but increases the complexity of conflict resolution and maintaining consistency guarantees.

Others use leaderless replication, where any node can accept reads or writes. These systems rely on quorum-based read/write protocols and are designed for high availability in distributed environments.

Replication raises some challenges:

Consistency: Read-after-write consistency is not guaranteed unless replicas sync immediately, which introduces latency.

Lag: In high-write environments, replicas can fall behind, returning stale data.

Failover logic: Automated promotion of replicas must be carefully designed to avoid split-brain scenarios.

Caching

Every system has a slow path. This can be the database that takes milliseconds to respond, the compute job that takes seconds to complete, or the API call that hits a rate limit.

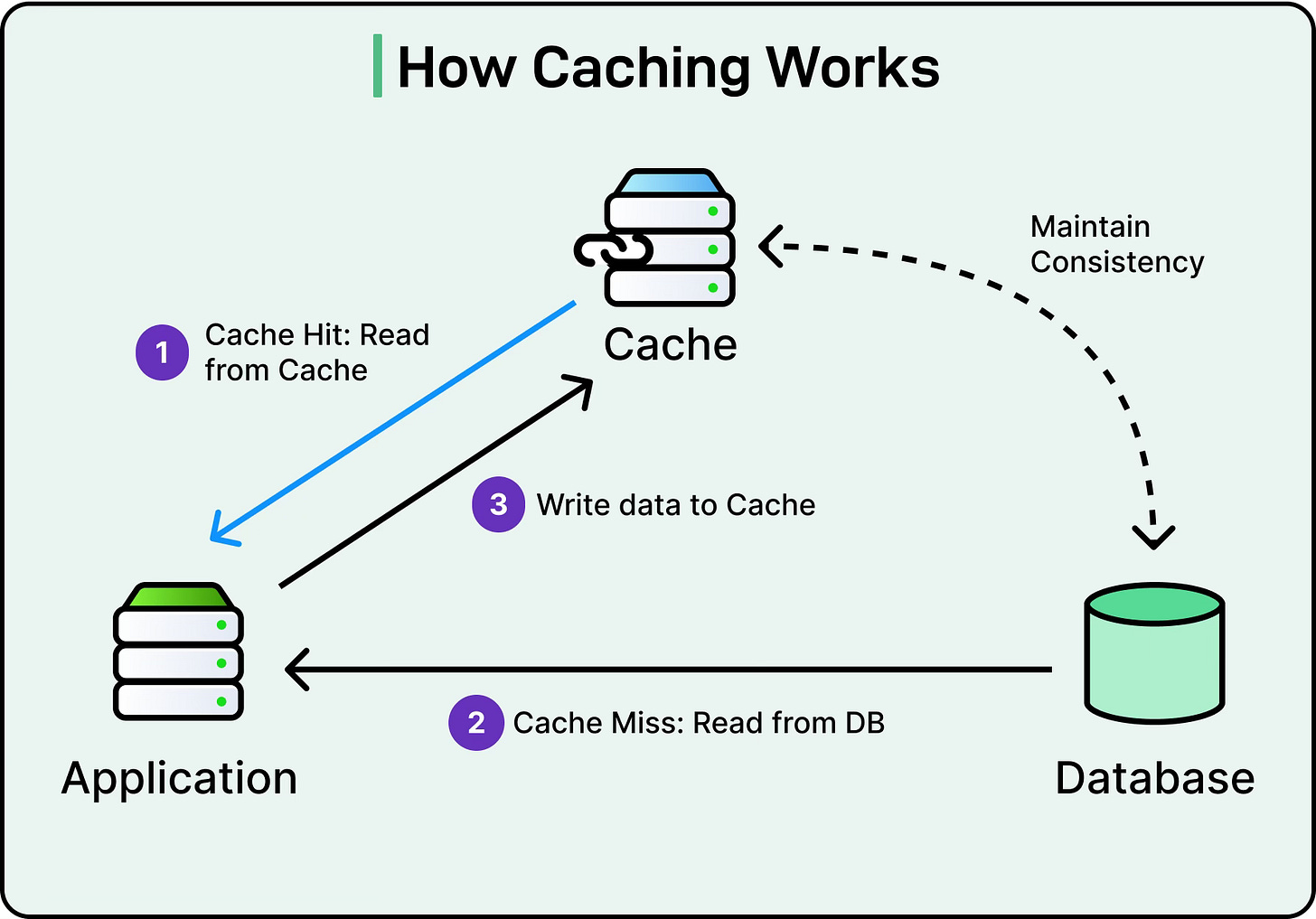

Caching sidesteps that path by serving precomputed or previously retrieved results from faster, more accessible storage. It reduces pressure on databases, improves response times, and absorbs sudden spikes in load.

See the diagram below for a basic example of caching.

Caching supports scalability in two primary ways:

Reduces repeated computation or database access, improving throughput under load.

Shortens response time, improving perceived performance and lowering infrastructure cost.

Caching shows up at multiple levels in modern systems, each solving a different bottleneck, such as:

Client-side caching happens in browsers, mobile apps, or front-end SDKs. It stores resources like images, API responses, and static assets locally to avoid redundant network calls. It’s fast and efficient, but fragile if cache invalidation isn’t handled well.

Application-layer caching uses in-memory stores like Redis or Memcached to hold frequently accessed data. It’s commonly used for storing user sessions, authorization tokens, configuration flags, or precomputed results. Since it lives close to the application, it minimizes latency and reduces backend load.

Database query caching stores the results of expensive or repetitive queries. Some databases provide built-in support, while others rely on external layers. For instance, caching the results of a slow JOIN or an aggregated count reduces repeated hits to underlying tables.

Edge caching via CDNs places content close to users by caching static or dynamic responses at edge servers around the world. This reduces both latency and origin traffic, especially useful in high-traffic, globally distributed systems.

Practical Design Considerations and Trade-Offs

Scalability isn’t a checklist but a system-wide property that emerges when multiple strategies work together.

Each solves a different problem and introduces trade-offs that need to be considered. Some points to keep in mind are as follows:

Stateless services are easy to scale horizontally, but they still rely on stateful backends. Those backends (databases, caches, message brokers) must be designed to scale as well. A system with 50 API instances won’t survive if all of them hit a single relational database that can’t handle concurrent load.

Auto-scaling adds elasticity but only works when metrics are meaningful and thresholds are tuned. If a system reacts too quickly to spikes, it may over-provision and waste resources. If it reacts too slowly, it may get overwhelmed before new instances come online.

Sharding improves write throughput, but introduces operational overhead. It’s harder to query across shards. It requires careful key design. And rebalancing under load is risky. Replication helps with read performance and availability, but it doesn’t eliminate write bottlenecks or consistency problems. Caching boosts speed but adds complexity around invalidation, consistency, and memory pressure.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at several scaling strategies along with their trade-offs and design considerations.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Scalability is the system’s ability to handle a growing load without degrading performance or reliability.

Vertical scaling adds more resources to a single machine but hits hardware and fault tolerance limits quickly.

Horizontal scaling distributes load across multiple machines, making it the preferred model in distributed, cloud-native architectures.

Stateless components are easier to scale because they don't retain session data. Stateful components require careful coordination to scale reliably.

Kubernetes supports auto-scaling at the pod, resource, and node levels through HPA, VPA, and Cluster Autoscaler, respectively.

AWS provides infrastructure-level auto-scaling for EC2, ECS, and RDS, triggered by CloudWatch alarms and scaling policies.

Sharding divides data across partitions to scale write throughput, but requires smart key design and careful operational handling.

Replication copies data to improve read performance and availability, but introduces challenges like lag and consistency trade-offs.

Caching reduces load on databases and compute layers by storing frequently accessed data in faster storage layers.

Each scaling technique solves a different problem. Real-world systems combine them thoughtfully to handle growth.