On the modern web, speed is a critical factor. When a page takes five seconds to load, conversion rates collapse. When it loads in under two seconds, engagement jumps and sales follow. The difference often comes down to how far the content has to travel.

Every request that crosses continents or bounces through congested networks adds milliseconds that pile up into seconds. Those seconds cost revenue, frustrate users, and put unnecessary strain on backend systems. Reducing that distance is one of the most effective levers for improving performance, and this is where a Content Delivery Network (CDN) comes into play.

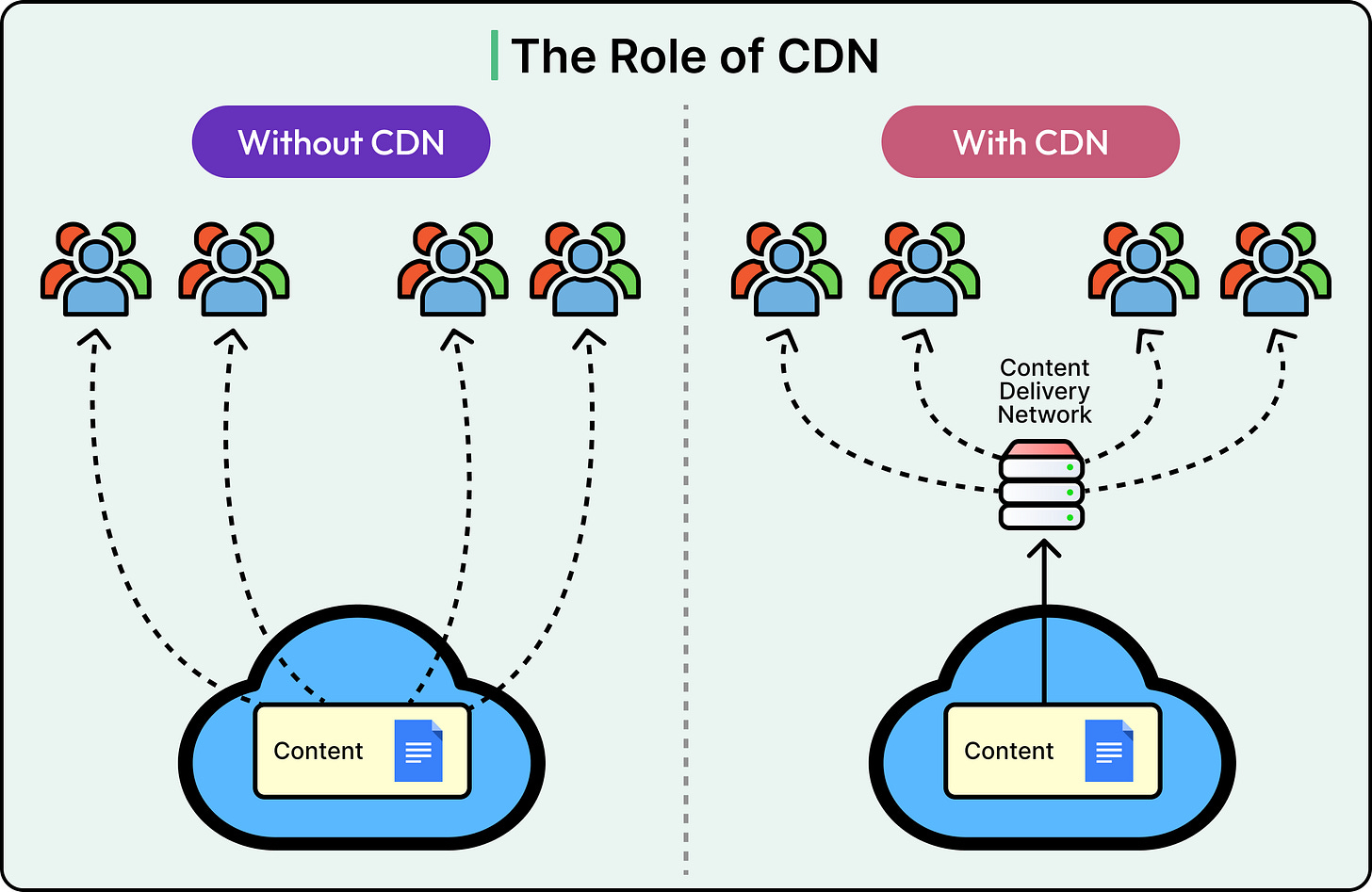

A CDN is a globally distributed set of servers that places content closer to the people who consume it.

Instead of every request going back to a single origin server, the CDN responds from an edge location near the user, cutting round-trip times and offloading work from the origin. It also increases availability, absorbs traffic spikes, and adds a defensive layer against malicious traffic.

Today, CDNs sit in front of most large-scale web and mobile applications. E-commerce storefronts, streaming services, and SaaS platforms rely on them to deliver consistent performance across continents.

Understanding how they work, where they fit, and how to tune them is essential for designing resilient, high-performance systems. In this article, we will explore how CDNs work, their trade-offs, and best practices.

Why the Need for a CDN

Serving content from a single origin works well when the audience is small and geographically close. As soon as the user base spreads across regions or continents, latency grows and reliability drops.

Several bottlenecks show up quickly:

Geographic distance: Packets still obey the speed of light. A request from Singapore to a server in New York takes hundreds of milliseconds each way, even under perfect conditions. Multiply that by multiple round-trip for assets, APIs, and authentication, and load times increase.

Network congestion: Public internet paths aren’t guaranteed to be optimal. Routing policies, peering agreements, and slowdowns can all add delays or drop packets.

Origin capacity: A single backend, even behind load balancers, has finite CPU, memory, and network bandwidth. A sudden spike (say from a flash sale or a viral post) can overwhelm it.

Bandwidth costs: Pushing large assets like images, videos, or software downloads repeatedly from the origin to distant clients drives up outbound data bills.

Security exposure: An origin directly exposed to the internet becomes a single point of attack. DDoS traffic, malicious scraping, and repeated exploit attempts hit it head-on.

A CDN addresses these pain points by distributing content to strategically placed servers across the globe. Requests hit the nearest edge location, reducing round-trip time and avoiding long-haul network hops. Popular assets are served directly from these edge caches, slashing repeated load on the origin.

The benefits are as follows:

Performance improves because content travels a shorter path.

Availability increases as the load spreads across many edge servers.

Scalability becomes easier since edges can absorb traffic bursts without immediately touching the origin.

Security hardens because edges filter, rate-limit, and absorb hostile traffic before it reaches backend systems.

Instead of every request pulling from the same central point, a CDN-supported system serves from many points in parallel, closer to the demand. That shift turns a fragile single-path delivery into a resilient, multi-path network.

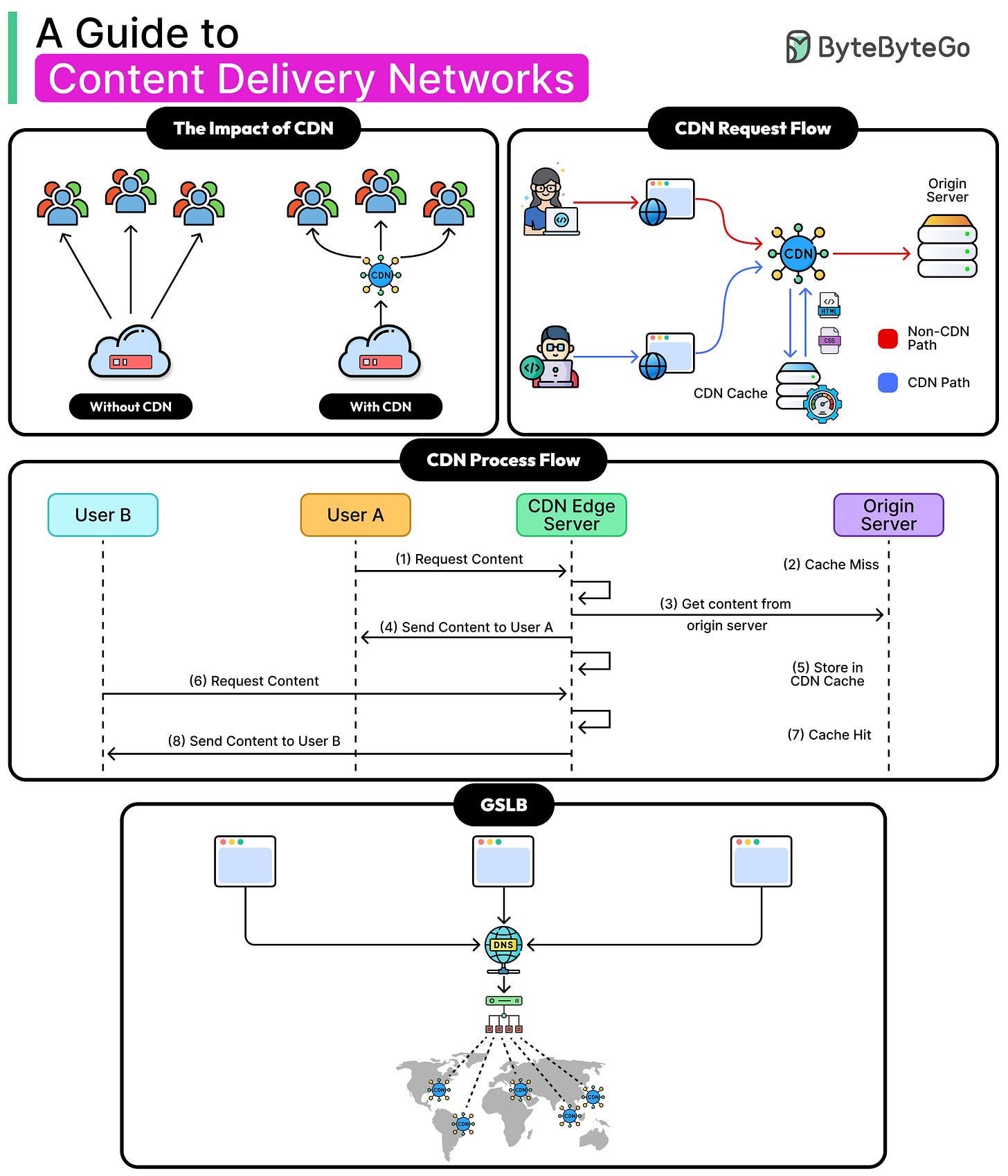

How a CDN Works (Step-by-Step)

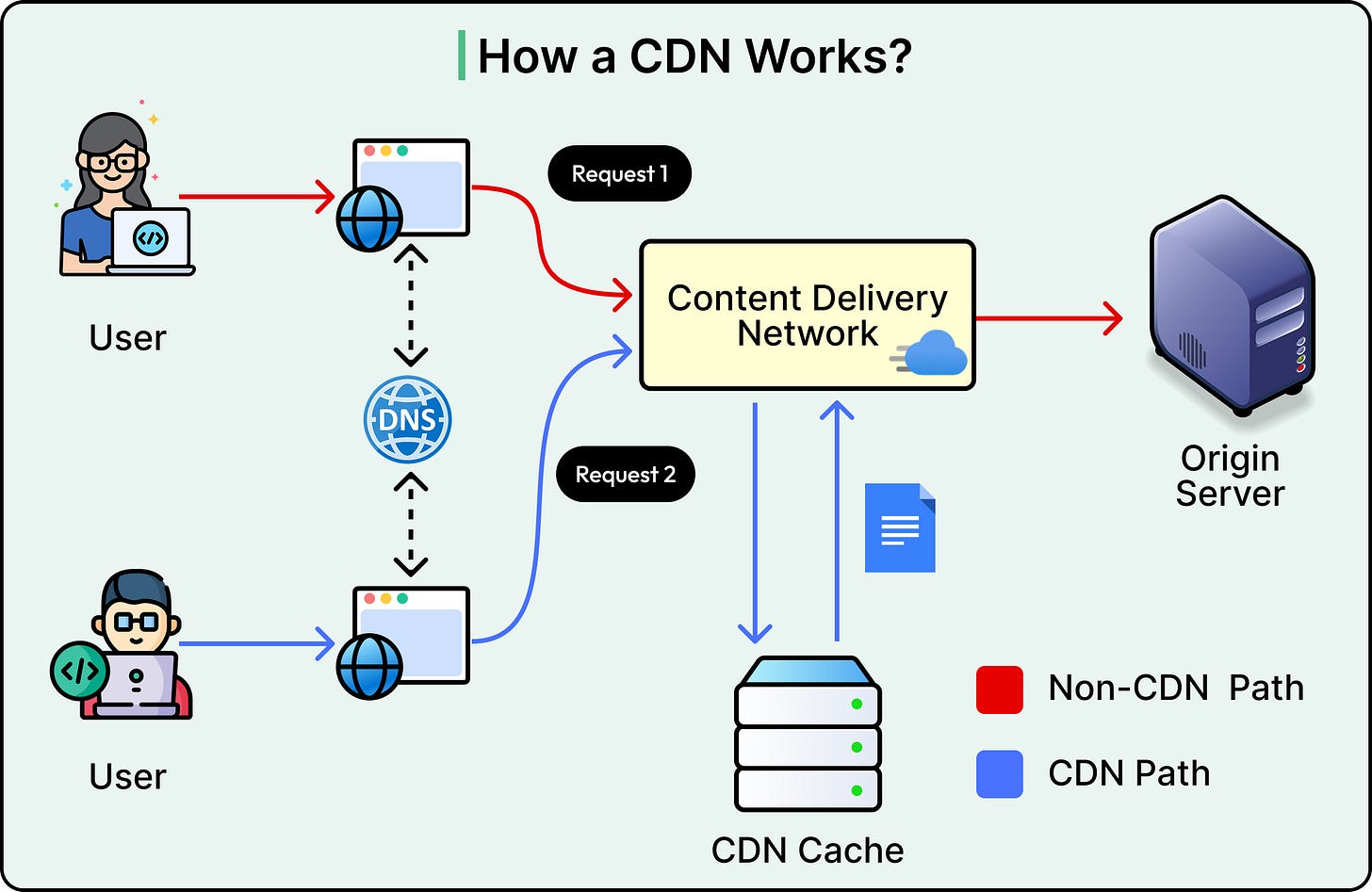

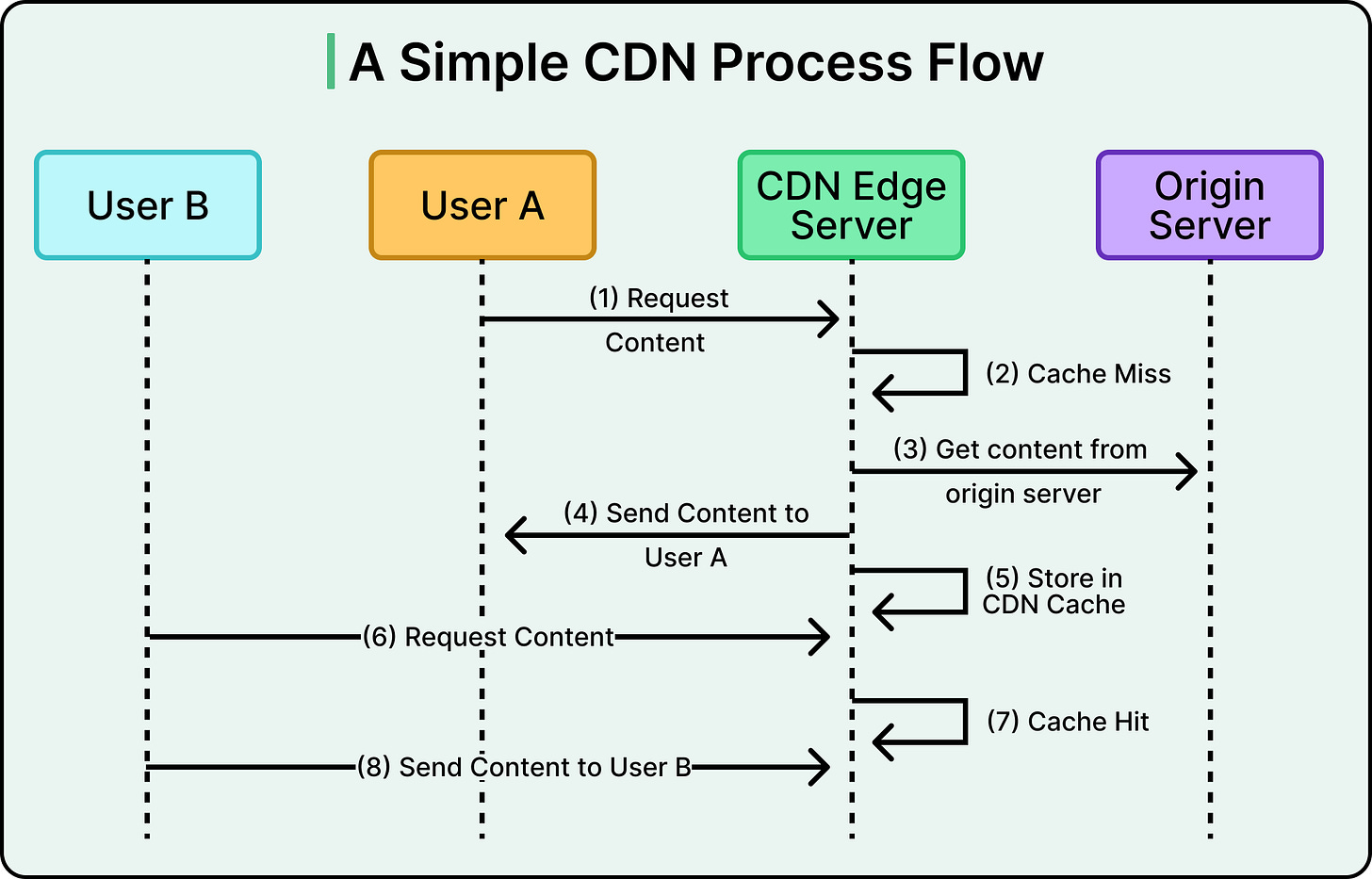

A CDN sits between the client and the origin, shaping the request path so that content is delivered from the most efficient source possible. The flow looks simple from the outside, but several coordinated steps make it happen.

Let’s look at the various steps below:

1 - DNS Resolution

When a browser or app requests content, it first needs to resolve the domain name to an IP address.

In a CDN setup, this query is handled by the CDN’s authoritative DNS service. Instead of returning the IP of the origin, the DNS system picks the optimal edge server based on factors like:

Geographic proximity to the client.

Current load on available edges.

Network health and latency measurements.

2 - Request Routing

Once the DNS response points to an edge IP, the client sends the HTTP(S) request there.

The routing decision (often aided by anycast networking) ensures the request travels the shortest practical path. This keeps latency down and reduces the chance of packet loss.

3 - Cache Lookup

The edge server receives the request and checks its local cache.

Cache hit: The object is present and fresh (TTL not expired). The edge immediately serves it.

Cache miss: The object is absent or stale. The edge proceeds to fetch it from the origin.

High cache hit ratios are the backbone of CDN efficiency. Every hit avoids an origin round-trip and reduces backend load.

4 - Origin Fetch

If the cache misses, the edge forwards the request to the origin server. This step is the costliest in terms of latency and resource usage.

The origin processes the request and returns the content to the edge.

See the diagram below that shows a simple process flow for CDN:

5 - Caching and Delivery

After receiving the object from the origin, the edge stores it with an assigned Time-to-Live (TTL).

The same object can now be served to other clients requesting it, without another trip to the origin.

6 - Optimization and Security Layers

Before sending the response, the edge can apply:

Compression and minification for smaller payloads.

Protocol upgrades like HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 for better multiplexing and lower latency.

Security filters such as TLS termination, Web Application Firewall (WAF) rules, and DDoS mitigation.

CDN Architecture and Components

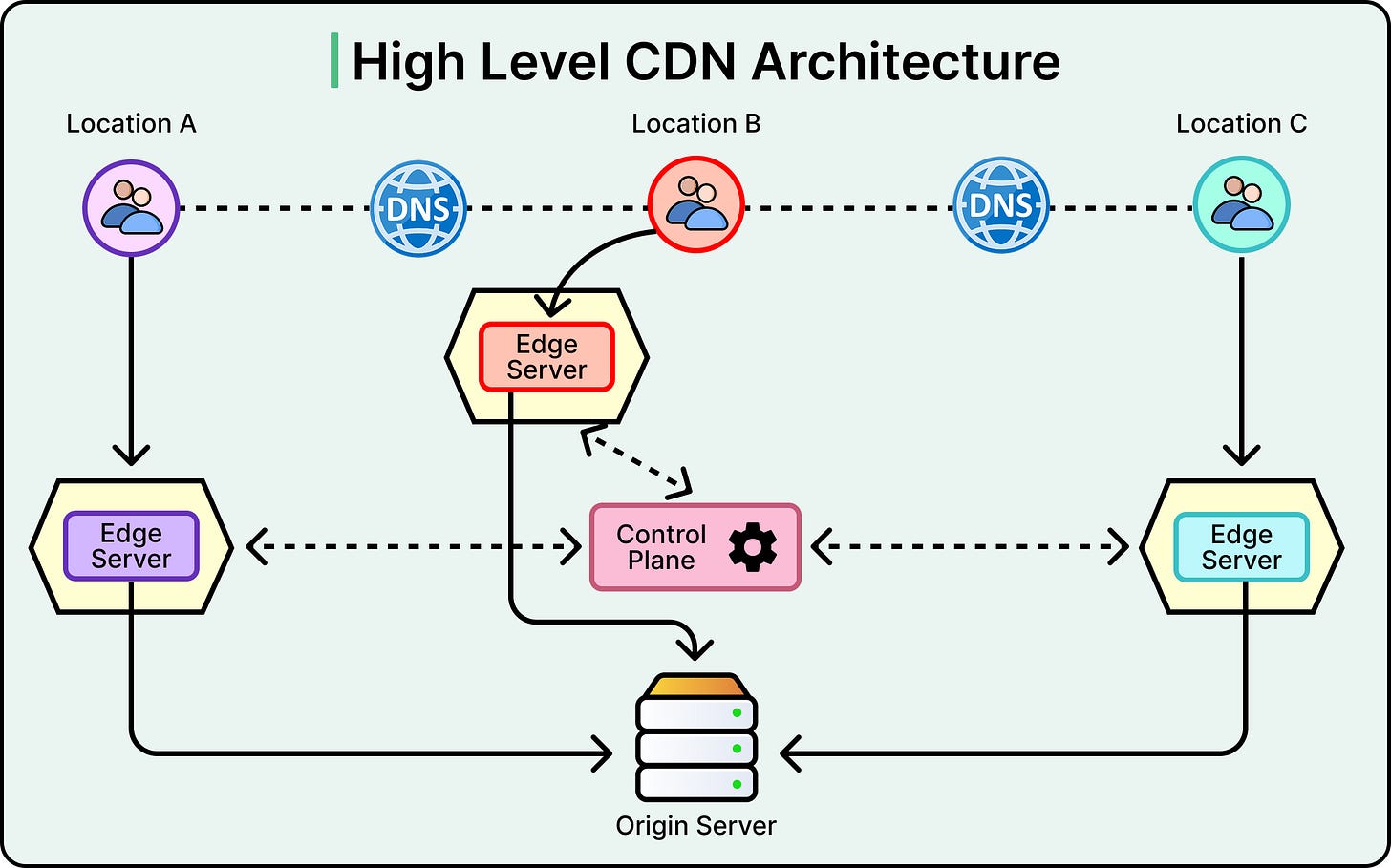

A CDN is not a single block of hardware or software.

It is a coordinated system of services, infrastructure, and control mechanisms. Understanding the role of each part makes it easier to tune performa troubleshoot issues, and plan capacity.

Let’s look at each component in more detail.

Origin Server

The origin holds the authoritative version of the content. It might be a single web server, a cluster behind a load balancer, or a cloud storage bucket serving static assets.

The origin responds when the CDN cannot serve a request from cache.

Keeping the origin secure and stable is critical since every cache miss depends on it. Origins often sit behind a restricted firewall, allowing traffic only from CDN edge IP ranges.

CDN Edge Servers (Points of Presence)

Edge servers are distributed in Points of Presence (PoPs) around the globe.

These are the first touchpoints for user requests after DNS resolution. They store cached copies of content and apply optimizations like compression and image resizing. They also enforce security rules before requests reach the origin.

Strategic placement of these servers ensures that most users connect to an edge within a few network hops.

Domain Name System (DNS)

DNS in a CDN setup does more than map names to IPs. It works with Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB) to direct requests to the best edge location based on proximity, load, and network health.

DNS latency directly affects the start of the request flow. However, misconfigured DNS can send users to suboptimal edges, increasing latency.

CDN Control Plane

The control plane manages configuration, deployment, and monitoring. From here, teams define caching policies, configure SSL certificates, push security rules, and trigger content purges.

It is usually exposed through a web portal, CLI, and API. Control plane availability matters for making changes, though it does not serve traffic directly.

Monitoring and Analytics

Continuous measurement keeps the CDN effective.

Metrics such as cache hit ratio, origin fetch rate, response times, and error codes help detect performance regressions or capacity issues. Logs at the edge give visibility into how requests are routed and served. Aggregated analytics reveal usage patterns by geography and content type.

Request Routing Techniques

Routing is the decision-making layer that determines which CDN server handles each incoming request.

Good routing minimizes latency, balances load, and avoids weak network paths. Poor routing does the opposite, sending users to congested or distant servers. There are a few ways by which effective routing is managed:

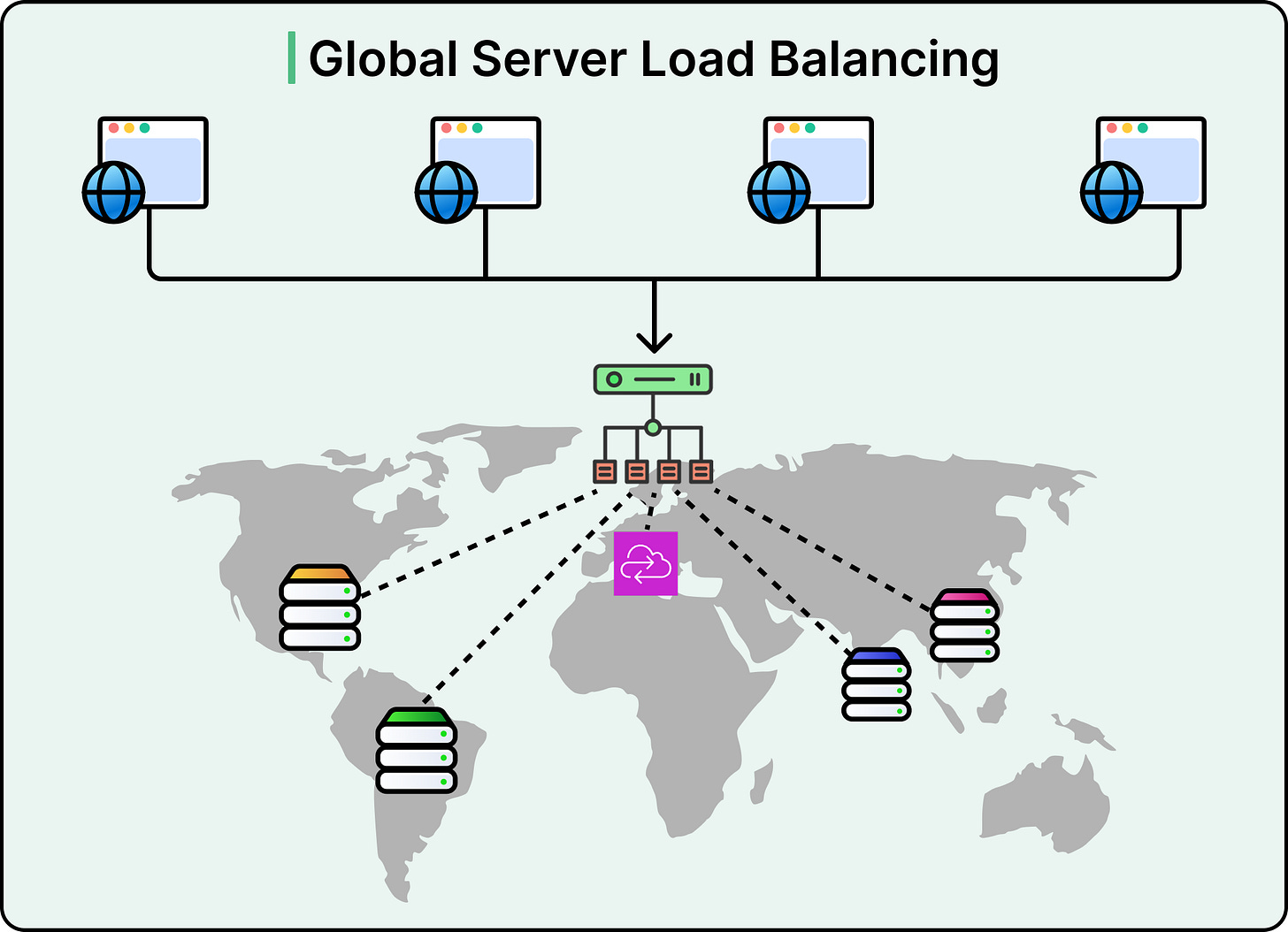

Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB)

GSLB distributes requests across multiple geographically separated servers or data centers. In a CDN, it often operates within the provider’s authoritative DNS service. The goal is to select the server that can respond fastest and most reliably.

Selection criteria typically include:

Geographic proximity to reduce round-trip time.

Current server load is to prevent bottlenecks.

Real-time network conditions, such as packet loss or high latency.

When a DNS query reaches the CDN’s authoritative servers, the GSLB system evaluates these factors before returning the IP address of the chosen edge location. This decision happens within milliseconds but directly influences end-user experience.

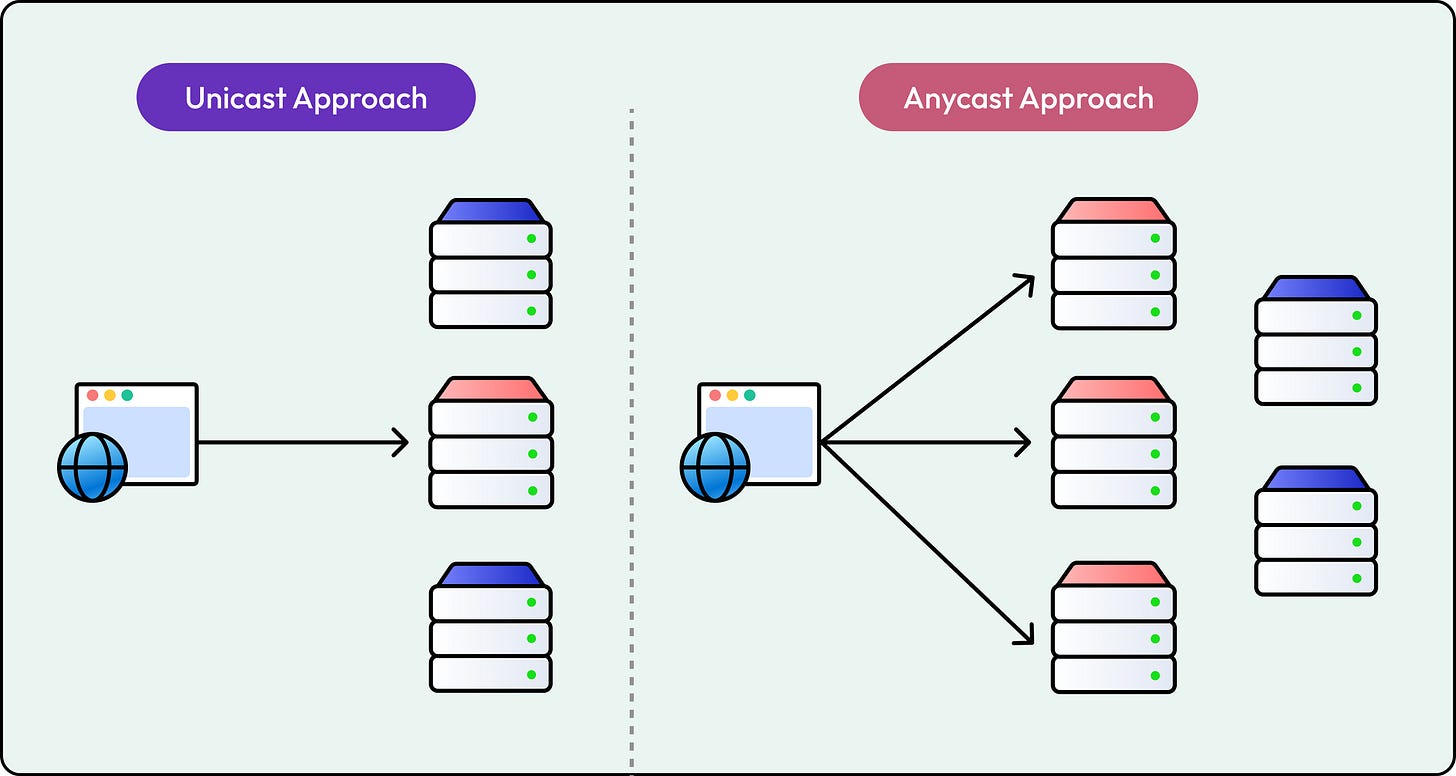

Anycast DNS

Anycast assigns the same IP address to multiple servers in different locations.

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) routing ensures that requests are sent to the nearest or best-connected server based on network topology.

The main benefits of Anycast are as follows:

Anycast helps absorb large-scale attacks by distributing malicious traffic across many endpoints.

It reduces the impact of localized outages because requests automatically shift to other available locations.

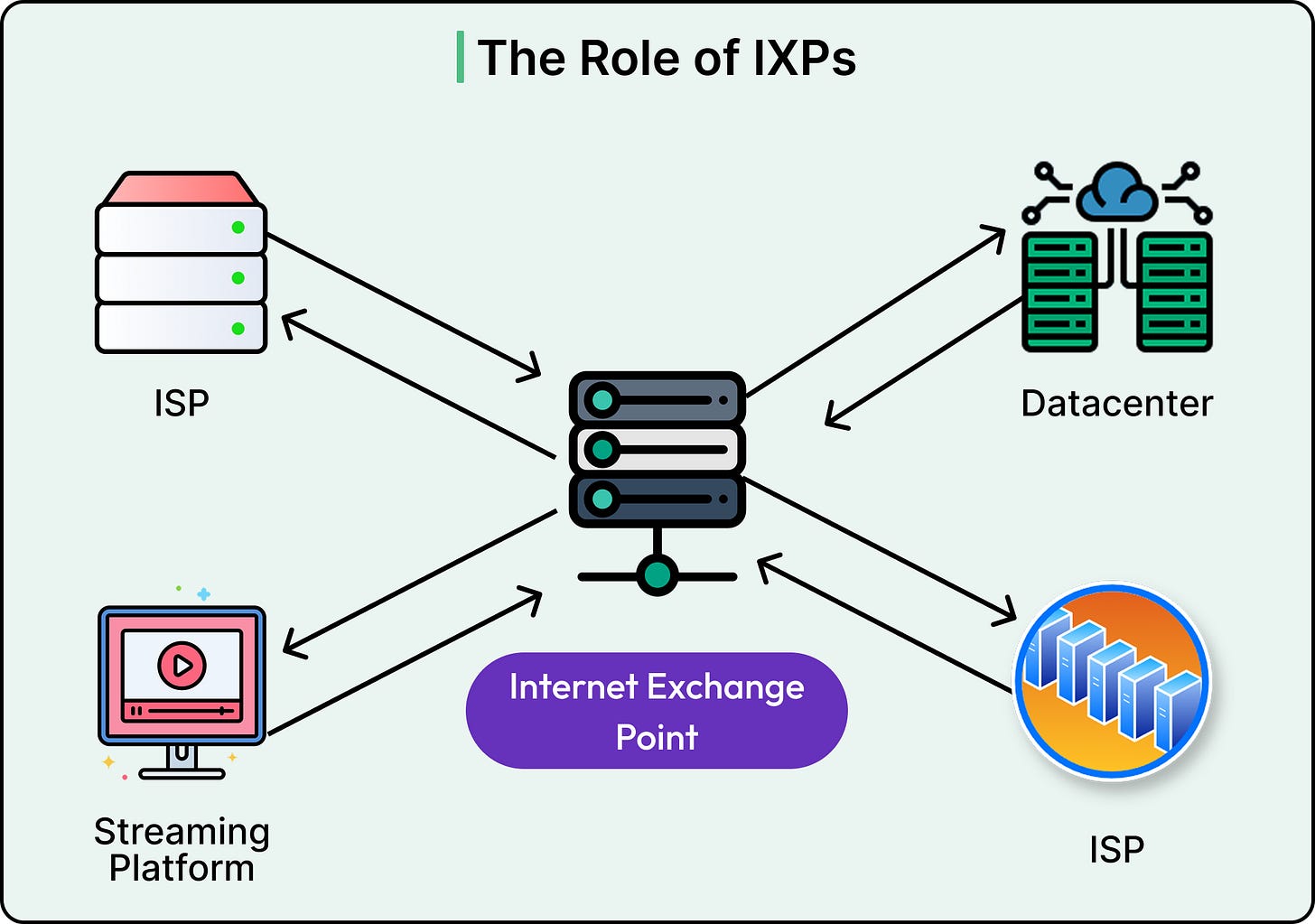

Internet Exchange Points (IXPs)

IXPs are physical facilities where networks interconnect to exchange traffic directly.

By placing CDN infrastructure at major IXPs, providers shorten the path between their edge servers and the user’s internet service provider.

The main advantages of this technique are as follows:

It helps reduce latency by avoiding unnecessary hops.

It also minimizes “tromboning”, where traffic takes a long detour before reaching a nearby destination.

Best Practices for Optimizing CDN Performance

A CDN can only perform as well as it is configured.

Misapplied settings or neglected maintenance turn it into an expensive pass-through instead of a performance booster. These practices help keep the edge fast, efficient, and secure.

Caching Optimization

Caching decisions have a direct impact on load times and origin health.

Some tips are as follows:

Set Time-to-Live (TTL) values based on content volatility. Longer TTLs work for static assets, while rapidly changing data needs shorter lifetimes.

Use cache-control headers to control freshness and revalidation.

Implement purge mechanisms to remove outdated content without forcing a full cache clear.

Track cache hit ratio to ensure policies are reducing origin traffic.

Content Optimization

Reducing payload size improves performance for all users, regardless of location.

Some important ways to do so are as follows:

Minify and compress HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

Serve images in efficient formats like WebP or AVIF, and tailor image resolution to device capabilities.

Apply lazy loading so non-critical assets load only when needed.

Pre-fetch or pre-render content likely to be requested next to cut perceived latency.

Network Optimization

Protocol and routing choices directly affect delivery speed. Some basic techniques are as follows:

Enable Anycast routing to direct traffic to the nearest healthy edge.

Use HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 for multiplexing, header compression, and better connection reuse.

Tune TCP settings like the initial congestion window and enable TCP Fast Open where supported.

Security Optimization

Performance and security are linked since malicious traffic can also slow or cripple a CDN. Here are some tips to handle this:

Terminate TLS at the edge with modern cipher suites and session resumption.

Deploy Web Application Firewall (WAF) rules to block common exploits before they reach the origin.

Enable DDoS mitigation to absorb volumetric attacks.

Keep edge software and configurations up to date to close vulnerabilities.

Summary

In this article, we’ve covered the concept and technical aspects of Content Delivery Networks in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

CDNs reduce latency, improve reliability, and protect origins by serving content from globally distributed edge servers closer to end users.

Serving from a single origin introduces latency, network congestion, higher costs, and greater security exposure; CDNs mitigate these by distributing load and filtering traffic at the edge.

The CDN delivery flow involves DNS resolution to the nearest edge, routing the request, checking the cache, fetching from the origin if needed, storing content with TTL, and applying optimizations and security before delivery.

Key components include the origin server for authoritative content, edge servers in Points of Presence for caching and optimization, DNS with load balancing, a control plane for configuration, and monitoring for performance insights.

Routing techniques such as Global Server Load Balancing, Anycast DNS, and Internet Exchange Points ensure requests take the fastest, most reliable path to an edge.

Performance optimization relies on tuning cache policies, compressing and minifying assets, using modern protocols like HTTP/2 and HTTP/3, and maintaining strong security measures at the edge.