Distributed systems fail all the time. There could be a node crashing, a network link going down, or a dependency timing out. It’s hard to predict when these things can happen.

The job of system design isn’t to eliminate these failures. It’s to build systems that absorb them, recover from them, and keep working through them. This is the reason why reliability becomes such an important system quality.

In a distributed setup, reliability doesn’t come from individual components. A highly available database, a fast API server, or a global load balancer on its own doesn’t guarantee uptime. Reliability emerges when all of these components interact in a way that tolerates failure, isolates blast radius, and maintains service guarantees under pressure.

There’s no single universal solution. What may work for a video streaming platform might not be suitable for a financial transaction system. However, some building blocks keep showing up again and again, irrespective of the domain. Here are a few examples:

Fault tolerance enables systems to remain functional even when components fail or behave inconsistently.

Load balancing distributes traffic evenly to avoid overloading any single node or region.

Rate limiting guards against abuse and overload by controlling the flow of incoming requests.

Service discovery enables services to locate each other dynamically in environments where nodes are added and removed frequently.Consistent hashing keeps distributed data placements stable and scalable under churn.

None of these solves reliability alone. But when combined thoughtfully, they form the foundation of resilient architecture. In this article, we will take a closer look at strategies that can help improve the reliability of a system.

Reliability and Fault Tolerance

Reliability means the system works consistently over a period and even during pressure situations. It's about uptime and correctness. For example, a search engine that returns corrupted results isn’t reliable, even if it never goes down.

Fault tolerance, on the other hand, is the ability to keep operating despite failures. A distributed system becomes fault-tolerant when it absorbs disruptions without passing those failures directly to the user.

As mentioned, failures in distributed systems are quite common. Here are some basic things that could go wrong:

Node crashes: A machine goes down mid-request. Without replication or retries, that request dies with it.

Network partitions: Services that usually talk to each other stop seeing each other.

Slow responses (latency spikes): Sometimes a service doesn’t fail, but just gets slow. Timeouts start to pile up, and retries kick in.

Out-of-memory or resource exhaustion: Saturated memory, file descriptors, or CPU can cause degraded behavior before an actual crash.

Software bugs and configuration drift: A bad deploy, an expired certificate, or a mismatched schema can introduce logical faults that are harder to detect.

Let’s now look at some common reliability and fault tolerance strategies that can boost reliability in a distributed system.

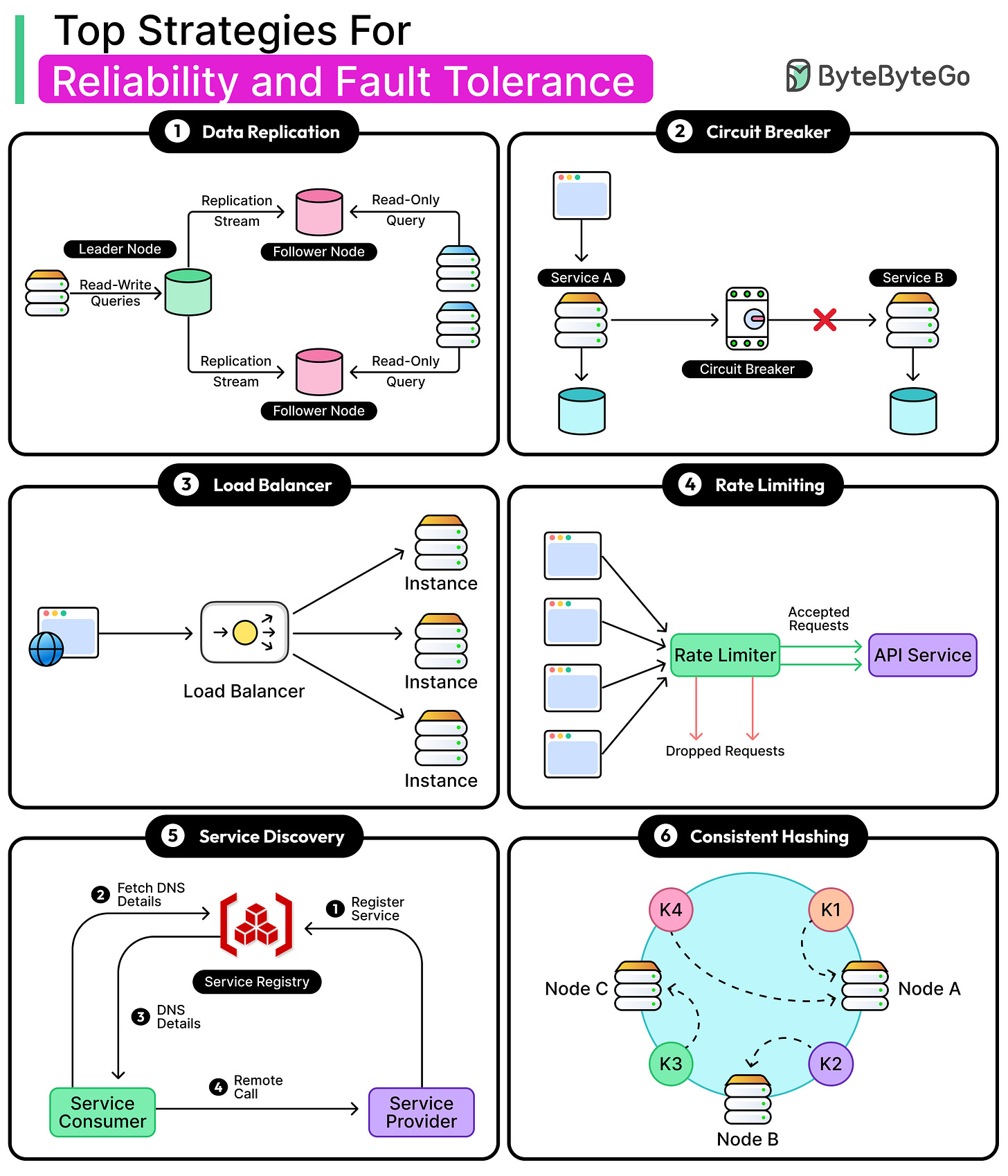

Data Replication

Replication is one of the most fundamental techniques of fault tolerance. It works by maintaining multiple copies of data or services, ideally in different failure zones, so that if one copy becomes unavailable, another can take over without disruption.

This sounds simple on the surface, but real-world replication introduces trade-offs around consistency, performance, coordination, and recovery.

Replication shows up in two main contexts: service-level and data-level.

Service-level replication involves running multiple instances of a stateless service (for example, API servers or microservices) behind a load balancer. This improves availability and throughput. If one instance dies, others continue handling traffic.

Data-level replication copies and synchronizes state across nodes, most critically in databases and storage systems. Here, consistency and conflict resolution become serious concerns.

Data replication models can be broadly classified into the following categories:

Leader-based replication (primary-replica): One node (the leader) handles all writes, and propagates changes to one or more followers. This model is simple and easy to reason about. However, failover can be complex if the leader crashes mid-write.

Multi-leader replication: Multiple nodes accept writes and propagate them to each other asynchronously. This improves write availability in geographically distributed systems but can introduce conflict resolution headaches.

Leaderless replication: Relies on quorum-based reads and writes, with no single point of coordination. Clients send requests to multiple nodes, and responses are combined based on consistency levels. This offers strong partition tolerance, but increases coordination complexity and risk of stale reads or conflicting writes.

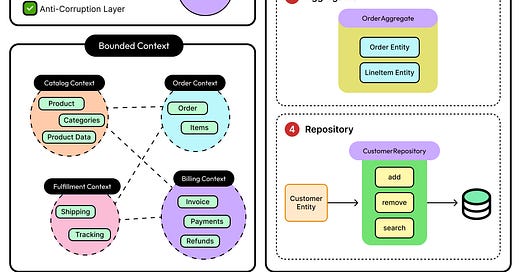

See the diagram below that shows leader-based replication.

Replication improves reliability by adding redundancy, but there are also trade-offs:

Consistency vs. Availability: The more nodes involved in confirming a write, the more consistent the system becomes. But it comes at the cost of higher write latency and reduced availability during partitions.

Performance Overhead: Syncing data across regions adds network and serialization overhead. Systems must choose between synchronous replication (safer, but slower) and asynchronous replication (faster, but riskier).

Conflict Resolution: In multi-leader or leaderless systems, concurrent updates can result in divergent replicas. Resolution strategies include last-write-wins, custom merge logic, or vector clocks.

Failure Recovery: Replication can delay system recovery if a failed node rejoins with stale or corrupted data. Anti-entropy protocols (like Merkle tree comparisons) or hinted handoff mechanisms are needed to repair data safely.

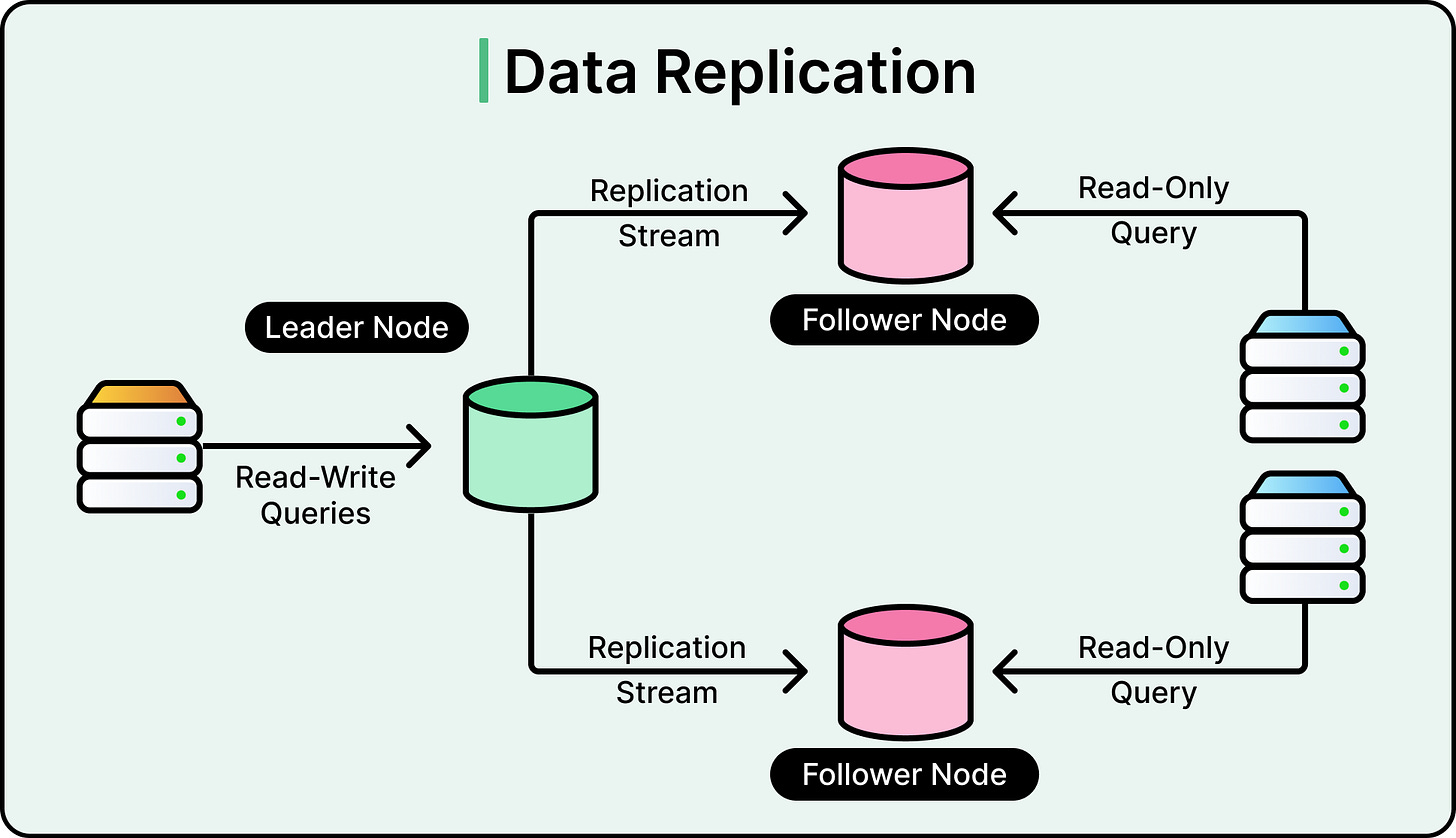

Failover

Failover is the mechanism that ensures the system keeps operating despite disruptions. It detects when something breaks, then automatically redirects traffic or promotes backups, so the system can recover without human intervention.

For stateless services, failover is usually straightforward. Load balancers monitor instance health using readiness checks or heartbeats. When an instance stops responding, it’s taken out of rotation and new requests flow to healthy replicas. This works well because stateless services don’t require coordination or data transfer during handover.

Stateful systems complicate the picture. When a database leader fails, it’s not enough to just promote a standby. The system must ensure that the new leader has the latest state, that no two nodes think they’re in charge, and that clients are routed correctly.

See the diagram below for the same:

These requirements make failover more fragile, especially under partial failure or network partitions. The critical question in failover is: how does the system know when to act?

Premature failover causes instability. Healthy components get kicked out due to temporary slowness or network jitter. Delayed failover leads to user-visible downtime.

Most systems walk this line using a combination of heartbeats, health probes, and request error rates.

Two common failover strategies dominate: active-passive and active-active.

In active-passive setups, a primary node handles traffic while a secondary waits silently. If the primary fails, the standby is promoted. This model is simpler and safer but comes with a recovery delay.

In active-active systems, all nodes share traffic, and any node can absorb extra load if one goes down. This model offers instant failover but requires load-awareness and state synchronization to avoid overload or inconsistency.

Systems that require a single authoritative leader, like distributed databases or consensus stores, use protocols like Raft or Paxos to handle failover through formal leader election.

These protocols prevent "split-brain" conditions, where two nodes mistakenly believe they are the leader and accept conflicting writes. However, they add latency and complexity, especially under high churn or slow networks.

Retries and Backoff

The basic idea behind retries is simple: if a request fails, wait and try again.

However, the reality is messier. Not all failures are temporary, and not all operations are safe to repeat. And if dozens or hundreds of clients retry simultaneously, they can flood an already struggling service, causing what should have been a small, recoverable failure to spiral out of control.

The classic example is a brief outage in a critical internal service. Clients immediately retry failed requests. The target service is already under load, and retries can double or triple the traffic. The system collapses under the weight of its recovery attempts. This is known as a retry storm, and it’s one of the fastest ways to amplify failure.

To prevent this, retries must be designed with a backoff strategy that introduces a delay between retries, giving the system time to recover. There are a couple of options available:

Fixed backoff adds a consistent delay between attempts.

Exponential backoff increases the delay with each retry attempt, reducing pressure during prolonged outages. Adding jitter (a random variation to the wait time) helps avoid synchronized retries across clients, which is critical in large-scale systems.

Exponential backoff with jitter is the default strategy in most production-grade clients. It balances retry speed with system protection and avoids synchronized retry spikes.

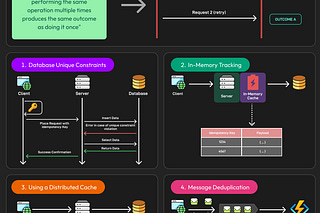

However, not all operations should be retried. Anything non-idempotent (like incrementing a counter or transferring funds) can cause duplicate effects if retried blindly. Systems must either guarantee idempotency or track request IDs to prevent duplication. This is why many APIs, especially in payment systems, require an idempotency key: a client-generated token that ensures a repeated request has the same effect as the original.

Retries also need limits. A failing dependency may not recover for minutes or at all. Infinite retries tie up resources, block queues, and delay error reporting. Most systems cap retries to a handful of attempts (typically three to five) before surfacing the failure upstream.

These decisions should align with the criticality of the operation and the likelihood of transient recovery.

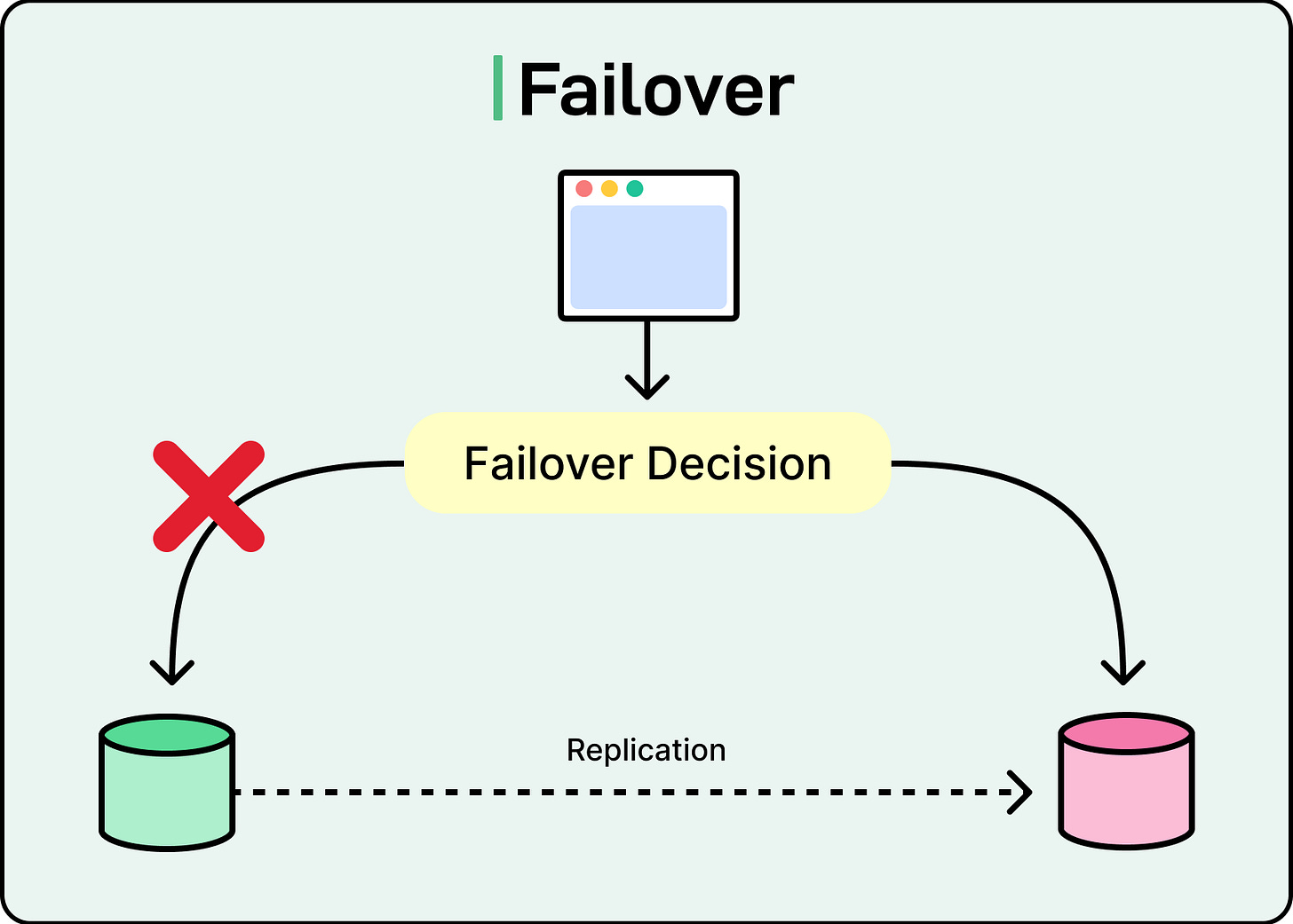

Circuit Breakers

Sometimes the best way to keep a system reliable is to stop calling the part that’s already broken. That’s the idea behind circuit breakers. They take inspiration from electrical systems: when current surges beyond safe limits, a circuit trips to protect the wiring. In distributed systems, the “surge” is usually retries, timeouts, or a sudden spike in error responses from a dependency.

Circuit breakers sit between services and monitor the flow of requests. When failure rates spike, they cut off further traffic temporarily, giving the failing service room to recover and preventing cascading overload across the system.

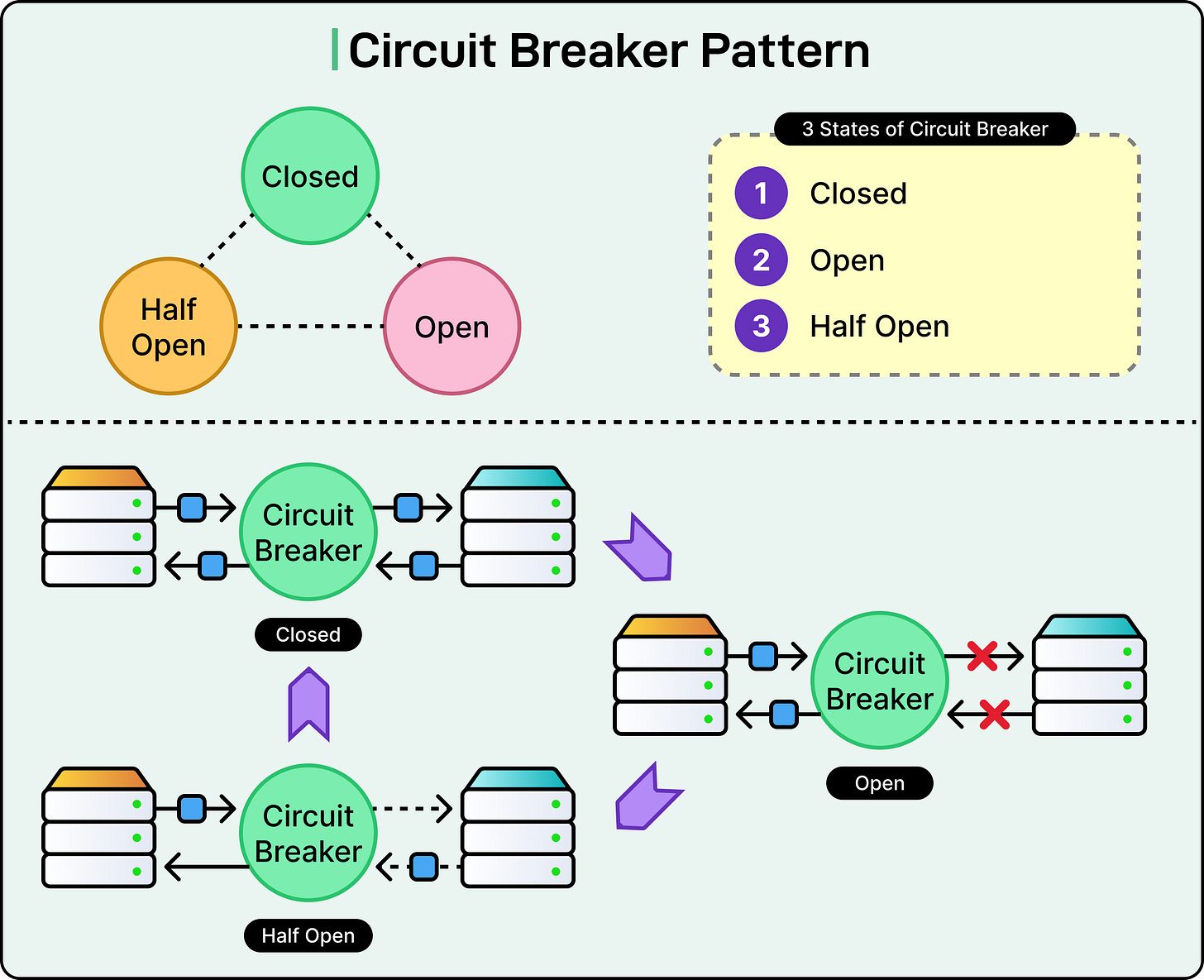

A circuit breaker can be in one of the following states:

Open: All requests are blocked. The dependency is considered unhealthy.

Half-open: A few test requests are allowed. Success leads to recovery.

Closed: Normal operation. Failures are tracked, but traffic flows freely.

For example, when a threshold of failures is reached (for example, 50% failures over a 10-second window), it trips. In the open state, the breaker rejects new requests immediately, often returning a fallback response or a fast failure. This prevents clients from hammering a broken service and allows downstream systems to stabilize.

After a cooldown period, the breaker transitions to a half-open state. A small number of requests are allowed through as a probe. If those succeed, the breaker moves to the closed state and resumes normal traffic. If failures continue, it reopens. This feedback loop protects both the failing service and the client systems relying on it.

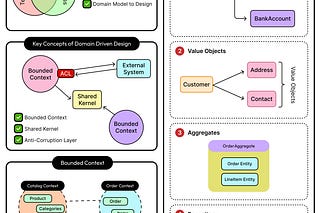

See the diagram below:

Circuit breakers are especially important when used in combination with retries. Without one, a failed service under heavy retry traffic can easily crash further. With a breaker in place, those retries are short-circuited before they reach the failing component. This saves resources and improves response times during failure.

That said, circuit breakers must be tuned carefully. If the threshold is too sensitive, the system may trip unnecessarily. If it’s too lenient, the breaker won't activate until it's too late. Developers must also decide what to return when the breaker is open. It could be a cached response, a fallback message, or an error.

Load Balancing

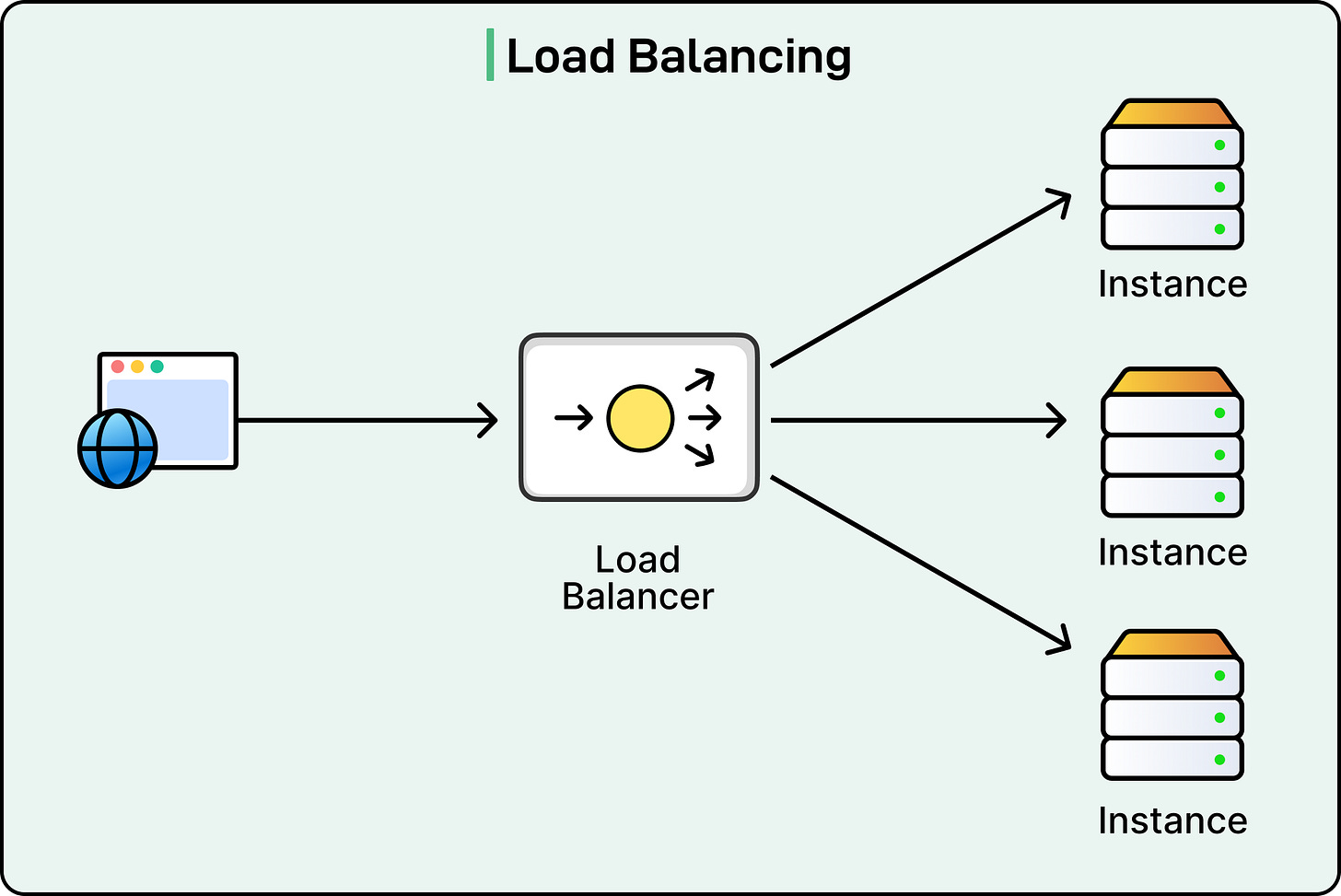

No matter how fast a server is, it will fail if overloaded. Load balancing solves that by distributing requests across multiple instances, zones, or regions, ensuring no single component becomes a bottleneck or a point of failure. It’s one of the simplest ways to increase availability and throughput, but it plays a critical role in the overall reliability of distributed systems.

At its core, load balancing answers one question: where should this request go?

The goal isn’t just to spread traffic evenly, but to do so intelligently, based on capacity, latency, availability, or even specific business logic. Poor load balancing can lead to hotspots, inconsistent performance, and increased risk of failure when one node gets overwhelmed while others are idle.

There are two broad categories of load balancing:

Layer 4 (Transport-level): Works at the TCP/UDP level, unaware of the actual request contents. This is fast and simple, but lacks routing flexibility.

Layer 7 (Application-level): Understands HTTP headers, cookies, and other metadata. This allows for smarter routing, like directing requests based on user type, device, or API endpoint.

Common algorithms include round-robin (cycling through servers), least-connections (choosing the least loaded instance), and weighted distribution (sending more traffic to beefier nodes). More advanced setups use latency-based routing, request hashing, or adaptive algorithms that react to runtime health metrics.

Rate Limiting

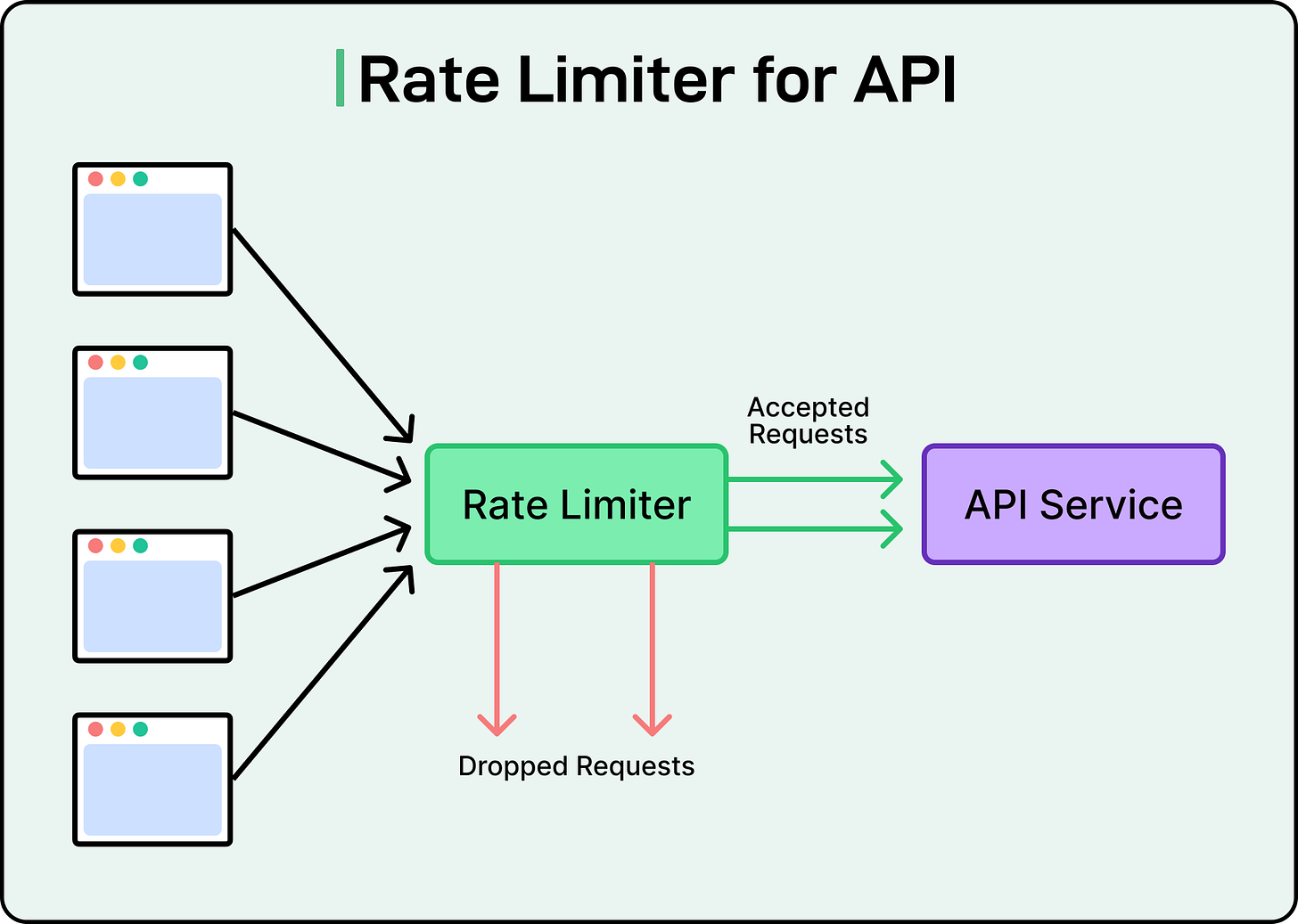

Every system has a breaking point. Sometimes traffic surges because of genuine user demand, such as a product launch, a viral post, or a flash sale. Other times, it’s a buggy integration gone rogue or a bad actor spamming the API.

Rate limiting helps enforce boundaries on how many requests a client can send, protecting services from overload, instability, and unintended abuse.

In distributed architectures, rate limiting is a reliability mechanism. Without it, downstream services can get overwhelmed by bursts of traffic, whether legitimate or malicious. Even retries can backfire: if a dependency starts failing and clients blindly retry, the resulting traffic spike can push it over the edge. Rate limiting helps control this feedback loop.

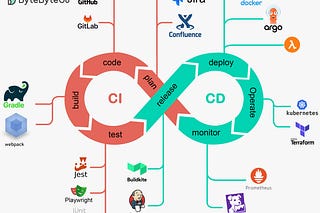

See the diagram below:

At a high level, rate limiting defines how many requests are allowed over a fixed time window, usually per user, IP, API key, or token. If the limit is exceeded, the system rejects further requests with an error (often HTTP 429 Too Many Requests) or queues them for later.

Several algorithms are used to implement rate limiting, each with trade-offs:

Fixed window: Counts requests in discrete intervals (for example, per minute).

Sliding window: Tracks requests across a moving time window for smoother enforcement.

Leaky bucket: Enforces a fixed outflow rate regardless of incoming burst size.

Token bucket: Refills tokens at a fixed rate. Clients spend tokens per request, allowing bursts up to a limit, then throttling.

These algorithms are typically implemented using in-memory stores like Redis or Memcached for fast, shared counters.

Rate limits must be tuned carefully. Too strict, and real users get blocked. Too loose, and the system risks being flooded. Good systems support tiered limits based on client roles or subscription levels. Some platforms also implement adaptive limits, tightening or relaxing thresholds based on system health or request success rates.

Service Discovery

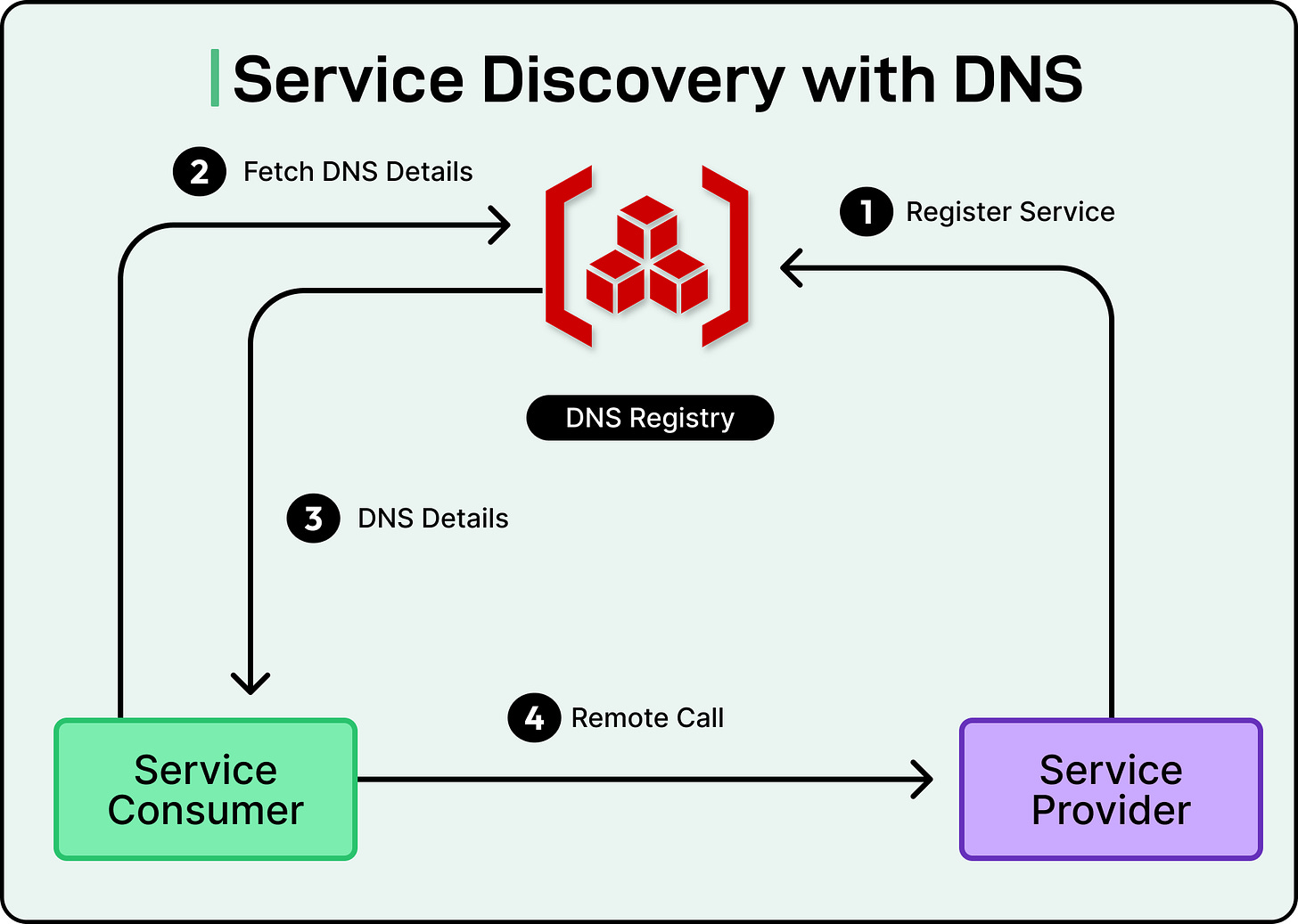

In static environments, services live at fixed addresses. However, modern infrastructure isn’t static. It’s dynamic, elastic, and constantly shifting. Containers get rescheduled, instances scale up or down, and services restart with new IPs.

In this scenario, hardcoded endpoints break systems fast. Reliability depends on knowing where healthy services are right now. That’s the job of service discovery.

Service discovery is the mechanism that lets one service locate another, not just by name, but by live, up-to-date information about where it’s running and whether it’s healthy. It ensures traffic only goes to available, responsive endpoints and shields systems from the fragility of manual configuration.

There are two broad models of service discovery: client-side and server-side.

In client-side discovery, the client itself queries a registry to get a list of available service instances. It then picks one and connects directly. This gives clients more control and can reduce proxy overhead.

In server-side discovery, clients send requests to a proxy or load balancer, which queries the registry and forwards the request to a healthy instance. This keeps client code clean and centralizes routing decisions.

Both models depend on the same underlying mechanism: a service registry. This registry maintains a constantly updated list of service instances and their health. For this to work reliably, three things need to happen:

Registration: When a service comes online, it announces itself to the registry. This often happens at startup or via automation from the orchestrator.

Health checking: The registry actively probes each instance or listens for heartbeats to detect failures. Unhealthy instances are removed from routing pools.

Deregistration: When a service shuts down or fails, it must be removed quickly to avoid blackholing requests.

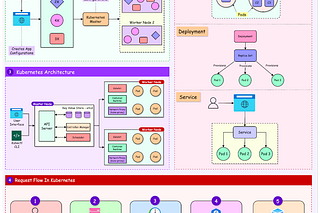

If any of these steps fail, reliability suffers. See the diagram below:

A node that isn’t deregistered keeps receiving traffic it can’t handle. A slow health check lets dead instances linger. A failed registration means the service is up but invisible to its callers.

Tools like Consul, Eureka, and Zookeeper have long handled service discovery in custom infrastructure. In containerized environments, Kubernetes DNS and its service abstraction (ClusterIP, Headless Service, etc.) make discovery native and declarative. In cloud-native setups, service meshes introduce an additional control plane that can discover, route, and secure service-to-service communication transparently.

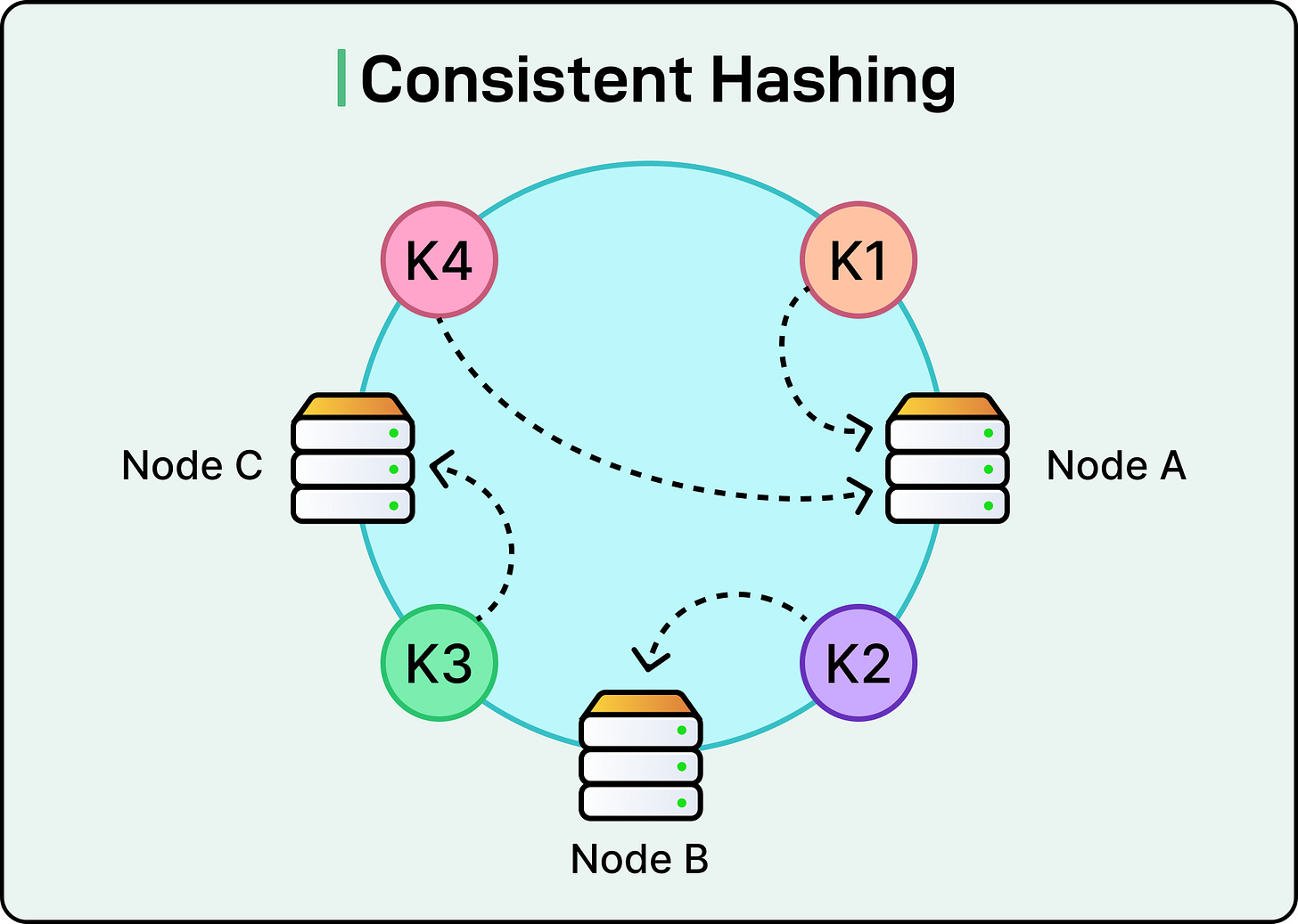

Consistent Hashing

In distributed storage systems, the hardest part often isn’t storing the data but knowing where it lives.

When nodes are added or removed, the system has to reassign keys to new destinations. If done naively, this reshuffling can be catastrophic: caches get invalidated, databases get overwhelmed, and availability takes a hit.

Most systems start with simple key partitioning: hash the key, then take a modulo of the number of nodes (hash(key) % N). This works fine when the number of nodes is fixed. However, in real systems, nodes can change due to scaling, failures, or rebalancing. Every time the value of N changes, nearly all keys get reassigned, forcing data movement and breaking cache locality.

Consistent hashing avoids this. It arranges both keys and nodes on a conceptual ring (a hash space). A key is assigned to the first node clockwise from its position on the ring. When a node is added or removed, only the keys that fall within its specific range are affected, usually around 1/N of the total keys, instead of all of them.

See the diagram below:

This minimal disruption is what makes consistent hashing so powerful.

To improve balance and avoid uneven key distribution (especially when nodes aren’t perfectly spaced), most implementations use virtual nodes. Each physical node is assigned multiple positions on the ring, distributing its share of keys more evenly. This also makes it easier to shift the load gradually by adding or removing virtual nodes rather than entire machines.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at reliability and fault tolerance strategies in great detail. Here are the key learning points in brief:

Reliability in distributed systems comes from designing for failure, replicating state, rerouting traffic, and isolating faults before they spread.

Fault tolerance techniques like replication, failover, and retries work together to keep systems responsive even when individual components fail.

Replication ensures that data and services remain available during failures, but requires careful handling of consistency and recovery to avoid data loss or divergence.

Failover shifts traffic or control from failed components to healthy ones, but must avoid false positives, split-brain scenarios, and overload on fallback nodes.

Retries help recover from transient errors, but without backoff and jitter, they can trigger retry storms that overwhelm already struggling systems.

Circuit breakers block traffic to failing dependencies, allowing them time to recover while protecting the rest of the system from cascading failures.

Load balancing spreads traffic across nodes to avoid hotspots and maximize availability, but must respond dynamically to health, latency, and capacity.

Rate limiting enforces traffic boundaries to prevent overload, abuse, and feedback loops from retries, ensuring system stability under stress.

Service discovery enables dynamic routing to healthy endpoints in environments where nodes scale or shift constantly, acting as the real-time source of truth for availability.

Consistent hashing provides a stable key-to-node mapping that minimizes disruption during scaling or failures, making distributed caches and storage systems predictable and efficient.