GraphQL is a modern way to build and use APIs. It was first created by Facebook in 2012 and later released as open source in 2015. Unlike the traditional REST approach, where the server decides what data is returned, GraphQL allows the client to ask for exactly what it needs. This simple shift makes APIs more flexible and efficient, especially when dealing with complex applications that use data from many different sources.

Over the past decade, GraphQL has grown into a powerful standard used by companies of all sizes. It helps developers avoid common problems such as downloading too much data or making multiple calls to get related information. At the same time, it enforces a well-defined structure through its type system, giving both backend and frontend developers a clear contract to work with.

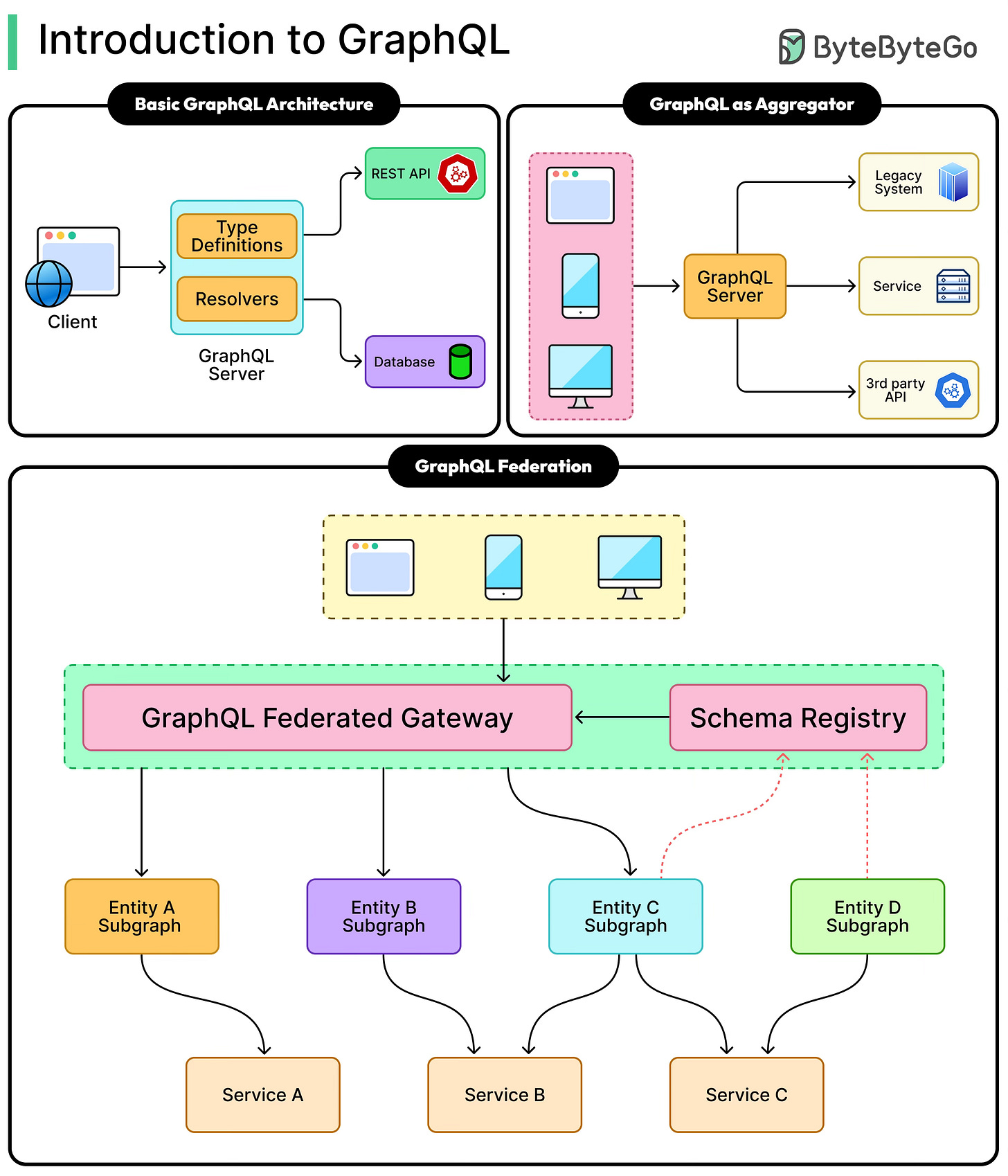

In this article, we will start with the basic concepts of GraphQL, covering how it works and why it has become so popular. From there, we will look at different ways GraphQL can be used as part of system architecture, from simple deployments to large-scale environments. Finally, we will explore advanced topics such as GraphQL Federation, which allows teams to manage APIs across many services in a unified way.

Why GraphQL?

Before GraphQL, most APIs were built using REST. REST has been the standard for a long time, and it works well in many cases, but it comes with limitations that become more noticeable as applications grow in complexity.

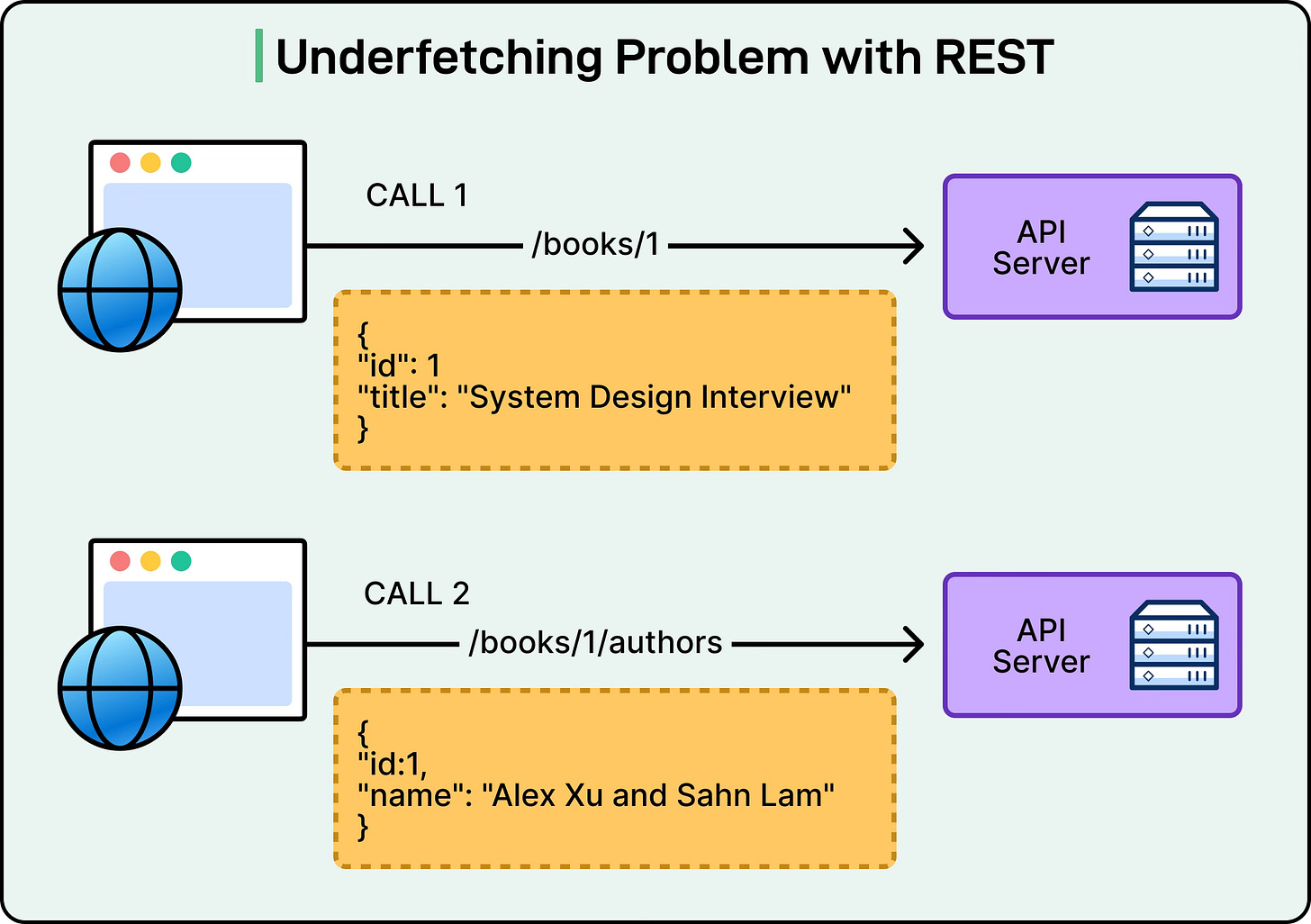

One common issue is over-fetching. With REST, an endpoint often returns more information than the client actually needs, forcing applications to download extra data. On the other hand, under-fetching is also a common issue. Sometimes a single endpoint does not provide enough data, so the client must make multiple requests to stitch everything together. Both situations lead to inefficiency and slower performance.

See the diagram below:

Another challenge with REST is versioning. When new features or fields need to be added, teams often create new versions of their endpoints, such as /api/v1/users and /api/v2/users. Over time, this creates maintenance overhead and confusion for both developers and clients who need to know which version to use.

REST also lacks a built-in type system, which makes it more challenging to ensure consistency between what the client expects and what the server provides. Developers often rely on documentation that can quickly become outdated. If something changes on the server without notice, the client can break without clear error handling.

GraphQL was designed to solve these problems in the following ways:

Instead of multiple endpoints, GraphQL exposes a single endpoint that allows the client to specify exactly what data it wants. This means no more over-fetching or under-fetching.

GraphQL also comes with a strong type system, which acts as a contract between the client and server. Clients can know in advance what fields are available, their data types, and how they relate to each other.

Finally, GraphQL avoids versioning problems by allowing APIs to evolve gracefully. Fields can be added without breaking existing queries, and older fields can be marked as deprecated so developers know to avoid them without disrupting current applications.

Core Concepts of GraphQL

At the heart of GraphQL are a few core ideas that make it powerful and flexible.

The most important concept is the schema. The schema defines the shape of your data and the relationships between different pieces of information. Think of it as a map of what clients are allowed to ask for. For example, a schema might say that a User has fields like id, name, and email.

Once the schema is in place, clients use queries to fetch exactly what they need. Instead of hitting multiple endpoints, a query specifies the fields directly. For example:

{

user(id: 1) {

name

email

}

}

This query will only return the name and email of the user with ID 1, nothing more. The response will look like this:

{

“data”: {

“user”: {

“name”: “Alice”,

“email”: “alice@example.com”

}

}

}To change or add data, GraphQL uses mutations. A mutation works like a query but is designed for updates. For example:

mutation {

createUser(name: “Bob”, email: “bob@example.com”) {

id

name

}

}This request creates a new user and returns the ID and name of that user.

GraphQL also supports subscriptions for real-time updates. Subscriptions let a client listen to changes and get notified immediately. For example, a client could subscribe to new messages in a chat:

subscription {

messageAdded {

id

text

sender

}

}Every time a new message is added, the client receives the data without having to make another request.

Behind the scenes, all of this works because of resolvers. Resolvers are functions on the server that fetch the actual data when a query, mutation, or subscription is executed. For example, the user query above might call a database function to retrieve user information.

Finally, GraphQL’s type system ensures that everything stays consistent. If the schema says email must be a string, the server cannot send back a number. This gives developers confidence that their APIs will behave as expected.

Together, schemas, queries, mutations, subscriptions, and resolvers form the foundation of GraphQL. Once you understand these building blocks, the rest of the ecosystem becomes much easier to follow.

How GraphQL Works in Practice

When a client makes a GraphQL request, the process follows a predictable lifecycle.

It begins with the client sending a query to the server. Unlike REST, where you often have multiple endpoints like /users/1 or /users/1/posts, GraphQL usually exposes a single endpoint such as /graphql. All queries, mutations, and subscriptions are sent to this one endpoint. The difference is that the request body contains the query itself, telling the server exactly what data the client wants.

Once the server receives the query, the first step is parsing and validation. The GraphQL engine checks the structure of the query and compares it to the schema. If a client requests a field that does not exist in the schema, the request is rejected right away. This validation step prevents errors and ensures that clients can only ask for fields that are actually supported.

After validation, the query moves to the execution phase. The server runs resolvers for each field requested. For example, if the client asks for a user’s name and email, the server will call the functions that fetch those fields from the database or another backend service. These resolvers can be simple or complex, depending on where the data lives, but they are always tied to the schema.

Finally, the server collects the results and sends back a structured response in JSON format. Importantly, the response mirrors the shape of the query. If the client only asked for name and email, the response will contain only those fields, nothing more. This is very different from REST, where endpoints often return a fixed set of data regardless of what the client actually needs.

To make the difference concrete, imagine a mobile app that needs just a user’s name. With REST, the app might call /users/1 and receive a full payload containing ID, email, address, and other fields, even if most of it goes unused. With GraphQL, the app sends a query asking only for the name, and the response contains exactly that. This efficiency becomes even more valuable in large applications with multiple clients, such as mobile, web, and IoT devices, each with different data needs.

In short, GraphQL simplifies the way clients and servers communicate. Instead of juggling multiple endpoints, everything flows through a single entry point, validated by the schema, executed by resolvers, and returned in the exact shape the client asked for.

GraphQL Architecture Possibilities

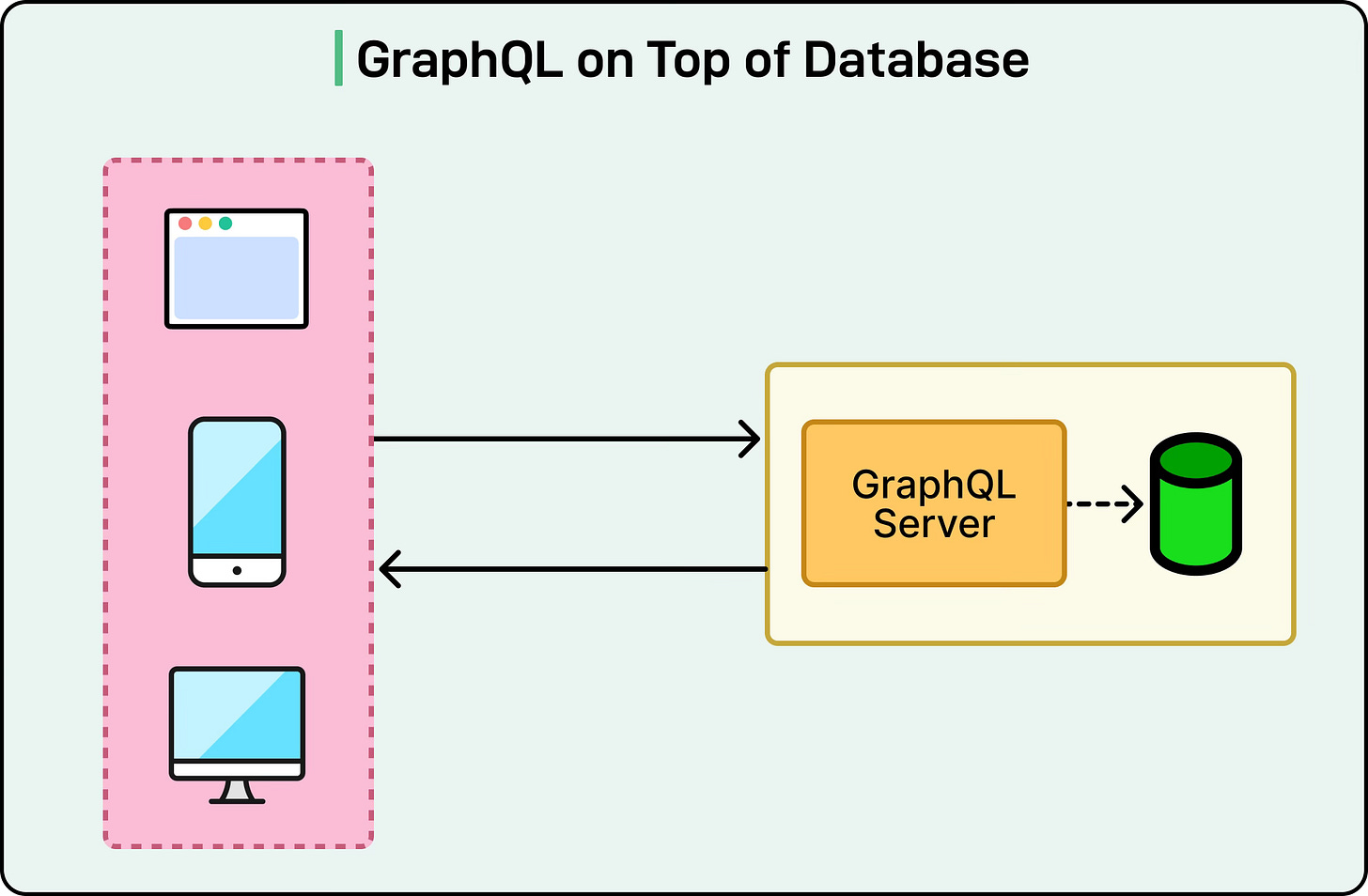

GraphQL is flexible enough to fit into different system architectures, and how you use it often depends on the complexity of your application and the variety of your data sources.

The simplest setup is when GraphQL sits directly on top of a single data source, such as a relational database. In this approach, each query or mutation in GraphQL maps directly to a database operation. For example, a user query might call a SQL statement like SELECT * FROM users WHERE id=1. This setup is straightforward and works well for smaller applications where all the data lives in one place.

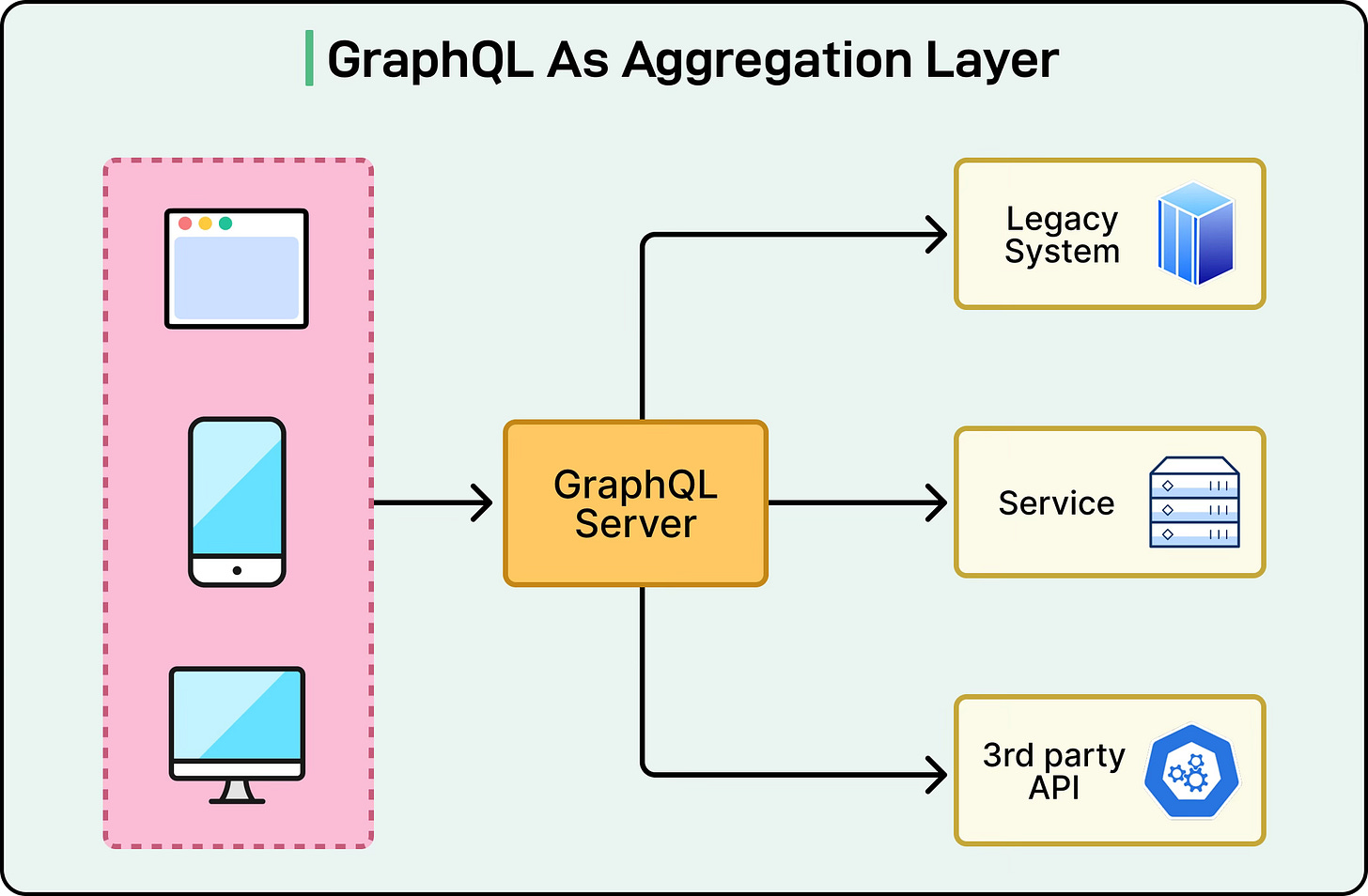

As systems grow, data rarely lives in just one database. Many modern applications use a mix of microservices, legacy systems, third-party APIs, and different types of databases.

In these cases, GraphQL works as an aggregation layer. Instead of clients having to call each backend system individually, the GraphQL server connects to all of them behind the scenes. The client still sends a single query, and GraphQL takes care of fetching the necessary pieces from multiple sources and combining them into a single response. This not only simplifies client code but also hides the complexity of the backend. See the diagram below:

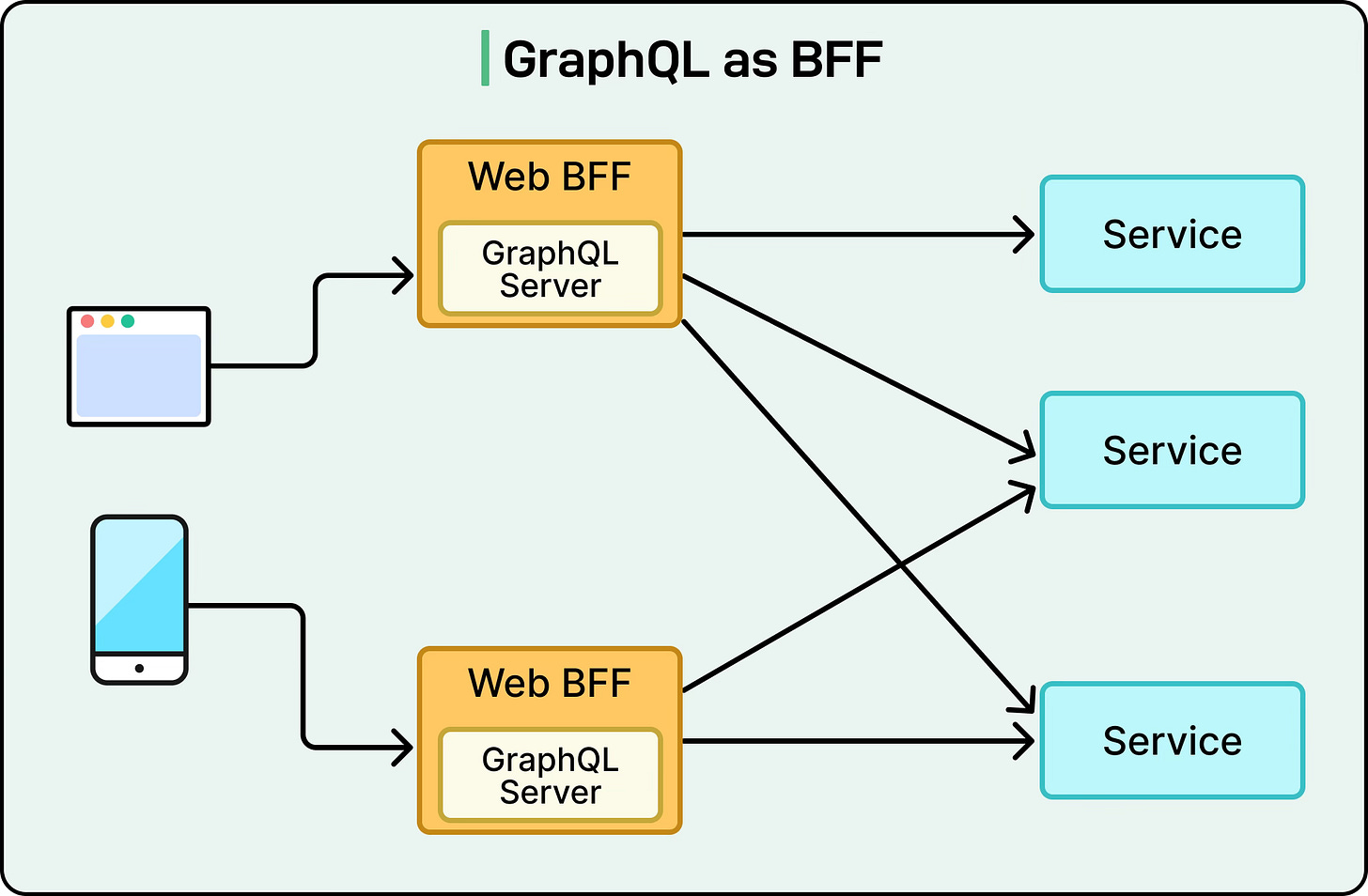

Another common pattern is using GraphQL as a Backend-for-Frontend (BFF) layer. In this style, GraphQL sits between the backend services and the client applications, providing each client with exactly the data it needs. For example, a mobile app may need smaller payloads to save bandwidth, while a desktop web app might request more detailed data for richer features. With GraphQL, both clients can send tailored queries to the same endpoint and get back optimized responses.

This avoids the need to build separate REST APIs or endpoints for each client type. These architectural choices make GraphQL very adaptable. Whether it’s powering a small app directly from a database, orchestrating multiple backend services, or tailoring data for different kinds of clients, GraphQL can fit into the system in a way that reduces complexity and improves efficiency.

GraphQL Federation: Scaling Beyond a Single Schema

When applications are small, it is often fine to put everything into one GraphQL schema. All the types, queries, and resolvers live together in a single service. However, as systems grow, this “monolithic schema” becomes hard to manage. Different teams may own different parts of the data, and keeping everything in one place can slow down development, create conflicts, and make the schema too large to work with effectively.

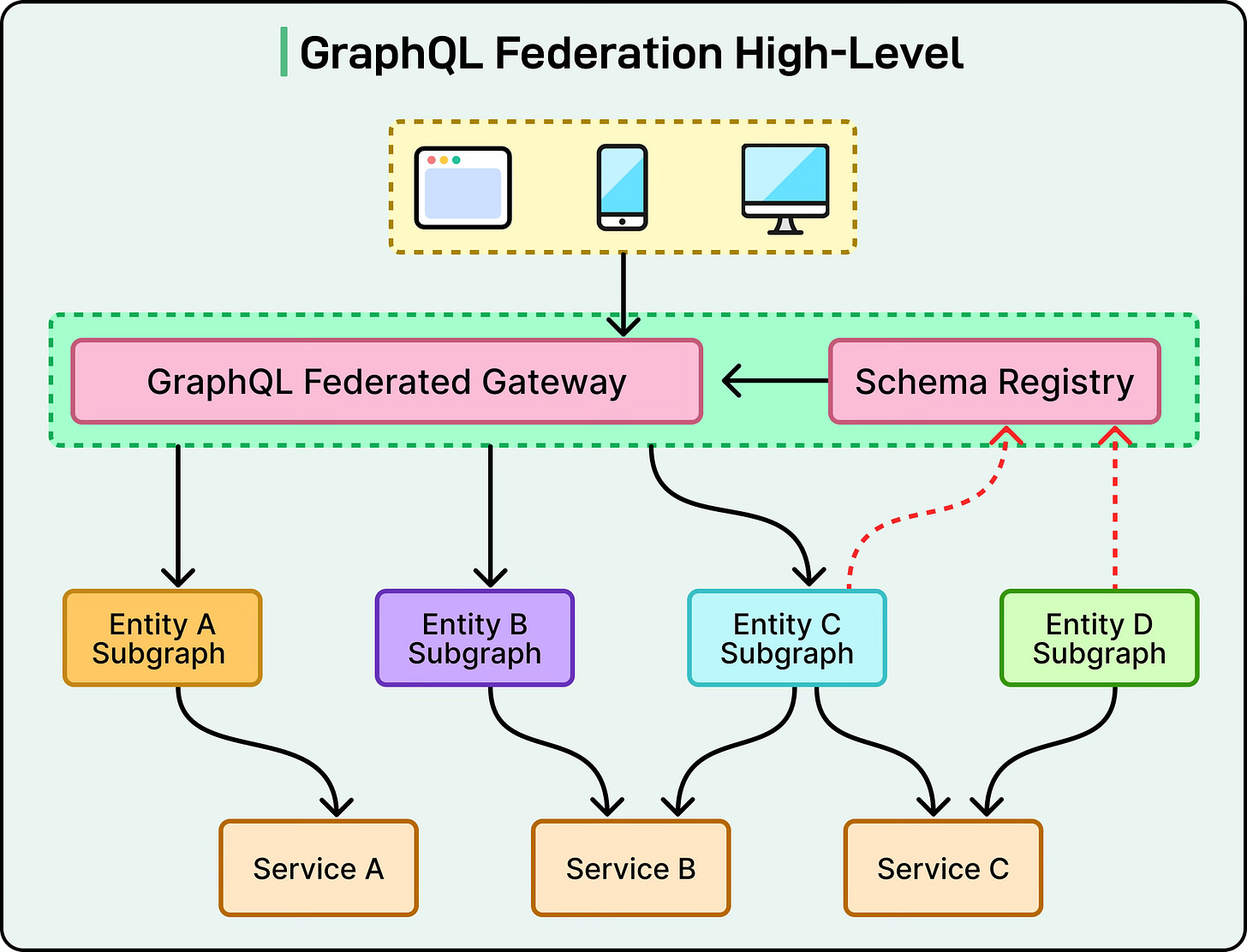

This is where GraphQL Federation comes in. Federation allows you to split a large schema into smaller pieces, each managed by its own service, while still giving clients the experience of querying a single unified graph. Each service defines the part of the schema it owns, and then these pieces are composed together into one schema that clients can use as if it were a single system.

A common implementation of this idea is Apollo Federation. In this approach, there are two main parts: the subgraphs, which are the individual GraphQL services responsible for their own slice of the schema, and the gateway, which sits in front and combines these subgraphs into one federated schema for the client. From the client’s perspective, nothing changes—they still send one query to a single endpoint—but behind the scenes, the gateway knows which subgraph to call for each piece of the query and merges the results together.

See the diagram below:

To make this work smoothly, GraphQL federation uses a few special concepts. For example:

The @key directive is used to tell the gateway how to uniquely identify an entity, such as a User, by its ID.

The @extends directive allows one service to add new fields to a type that was defined in another service. For example, the “accounts” service might define the User type, and the “orders” service could extend User to include an orders field.

Similarly, the @provides directive lets a service declare which fields it can supply when resolving a related type. These tools allow multiple services to collaborate on shared types without stepping on each other.

It’s worth noting that federation is different from schema stitching, which was an earlier attempt to combine multiple GraphQL schemas. Schema stitching often involved manually merging schemas and writing custom code to resolve overlaps, which could become complicated and brittle as systems scaled. Federation, on the other hand, was designed with large organizations in mind, where many teams contribute to a single graph in a structured and predictable way.

In simple terms, GraphQL Federation makes it possible to scale GraphQL across an organization. It keeps schemas manageable, allows teams to work independently, and still gives clients the simplicity of querying a single unified graph.

Real-World Use Cases of GraphQL

GraphQL is not just a theoretical improvement over REST. It is actively used by companies across industries to solve practical problems.

One of the most common use cases is in mobile applications. Mobile clients often have limited bandwidth and different data requirements compared to desktop applications. With REST, developers might have to build separate endpoints tailored for each platform, but with GraphQL, the same endpoint can serve both. A mobile app can request a small set of fields to minimize payload size, while a web client can fetch more detailed data in a single request.

Another major use case is microservice orchestration. Large organizations often have dozens or even hundreds of microservices, each responsible for a specific domain such as users, orders, or payments. Without GraphQL, clients may need to call multiple services and manage the complexity themselves. With GraphQL, a single query can pull together data from different microservices, giving the client one clean response. This makes life easier for frontend developers and reduces the need for tight coordination between teams.

GraphQL is also valuable in hybrid environments where new systems must work alongside legacy APIs. Many companies cannot replace their old systems overnight, but they can put a GraphQL layer on top of them. This allows clients to query legacy REST APIs, SOAP services, or even SQL databases through a single GraphQL endpoint. Over time, as legacy systems are replaced, the GraphQL schema can evolve while the client queries stay the same.

The GraphQL ecosystem has grown rapidly, making adoption easier. Tools like Apollo Server provide a production-ready GraphQL server with support for schema federation and advanced features. GraphQL Yoga offers a lightweight and flexible alternative for smaller projects. Platforms like Hasura allow developers to instantly generate GraphQL APIs on top of a database with minimal setup. GraphQL Mesh can connect multiple sources—REST APIs, gRPC services, or databases—and present them as one unified GraphQL schema. These tools lower the barrier to entry and allow teams to adopt GraphQL without rebuilding everything from scratch.

In short, GraphQL is being used in real-world scenarios to solve real challenges: serving diverse clients, simplifying microservice architectures, and bridging the gap between old and new systems. The growing ecosystem of tools ensures that teams can find an approach that fits their needs, whether they are just starting or operating at enterprise scale.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at GraphQL in detail. Here are the key learning points in brief:

GraphQL was created at Facebook and open-sourced in 2015 as a modern alternative to REST for building APIs.

It solves common REST problems like over-fetching, under-fetching, versioning complexity, and lack of strong typing.

The core building blocks include schemas, queries, mutations, subscriptions, resolvers, and a strict type system.

A GraphQL request goes through parsing, validation, resolver execution, and returns a JSON response shaped exactly like the query.

GraphQL can be deployed in different architectures: directly on a database, as an aggregation layer for multiple services, or as a Backend-for-Frontend (BFF).

GraphQL Federation enables large-scale adoption by splitting schemas into smaller subgraphs managed by different teams and unifying them through a gateway.

Federation is more scalable and structured than earlier schema stitching approaches, especially for organizations with many microservices.

Real-world use cases include optimizing mobile applications, orchestrating microservices, and bridging legacy systems with modern clients.