Consider how a food delivery application works when someone places an order.

The app needs to know which restaurants are currently open, where they’re located, whether they’re accepting orders, and how busy they are. If a restaurant closes early or temporarily stops accepting orders due to high demand, the app needs to know immediately. This information changes constantly throughout the day, and having outdated information leads to failed orders and frustrated customers.

Modern software applications face remarkably similar challenges.

Instead of restaurants, we have services. Instead of checking if a restaurant is open, we need to know if a payment service is healthy and responding. Instead of finding the nearest restaurant location, we need to discover which server instance can handle our request with the lowest latency. Just as the food delivery app would fail if it sent orders to closed restaurants, our applications fail when they try to communicate with services at outdated addresses or send requests to unhealthy instances.

In today’s cloud environments, applications are commonly broken down into dozens or even hundreds of services. These services run across a dynamic infrastructure where servers appear and disappear based on traffic, containers restart in different locations, and entire service instances can move between machines for load balancing.

The fundamental question becomes: how do all these services find and communicate with each other in this constantly shifting landscape?

In this article, we look at service discovery, the critical system that answers this question. We’ll examine why traditional approaches break down at scale, understand the core concepts, and patterns of service discovery.

Life Before Service Discovery

The simplest approach to service communication is hardcoding the network addresses directly in the application configuration.

If an Order Service needs to call a Payment Service, we might simply configure it with the payment service’s location:

payment_service_url = “http://192.168.1.50:8080”

This straightforward approach works perfectly fine when we’re dealing with a handful of services that rarely change.

Let’s examine what happens in practice with this approach.

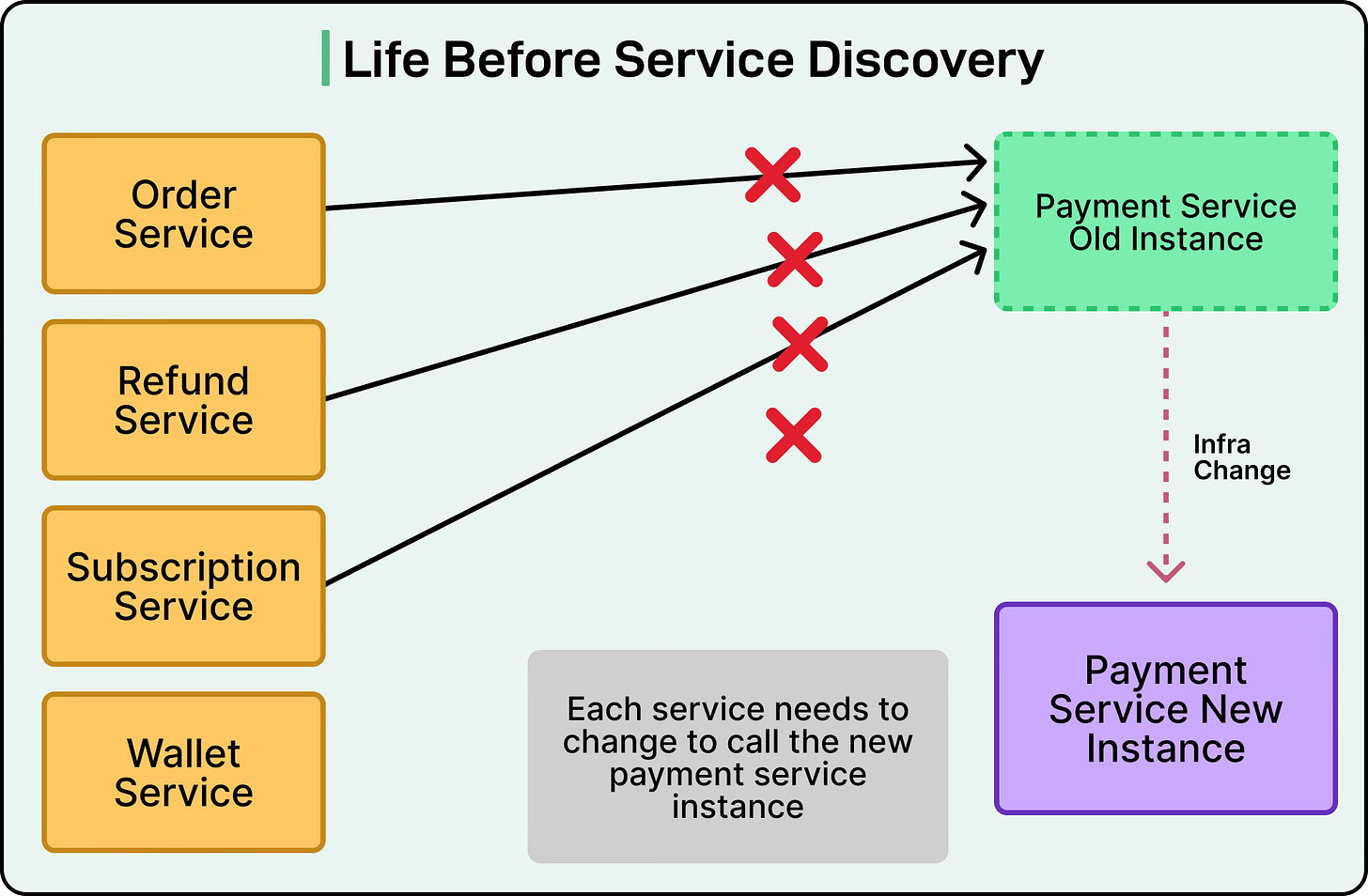

Imagine an e-commerce platform where the Order Service processes customer purchases by calling the Payment Service to charge credit cards.

Initially, the Payment Service runs on a single server at that fixed IP address.

Everything works smoothly until that server needs maintenance, or worse, crashes unexpectedly.

When the Payment Service moves to a new server at a different address, problems cascade through the system.

The Order Service continues sending requests to the old address, causing all payments to fail.

To fix this, someone must manually update the configuration file in the Order Service and restart it.

However, the Order Service isn’t the only service calling the Payment Service.

The Refund Service, Subscription Service, and Wallet Service all have the same hardcoded address. Each one needs its configuration updated and restarted, causing widespread disruption.

See the diagram below for reference:

Modern cloud environments make this problem exponentially worse.

Services now run in containers that can start on any available server. Auto-scaling creates new service instances when traffic increases and destroys them when traffic decreases. Cloud platforms might move services between physical machines for resource optimization. An instance that was at one IP address in the morning might be at a completely different address by afternoon.

The maintenance burden quickly becomes unsustainable. With dozens of services, each potentially calling several others, configuration changes become a full-time job.

A single service relocation might require updating configuration files across twenty different services, coordinating restarts, and hoping nothing breaks in the process. This fragility and operational overhead made it clear that hardcoding addresses couldn’t scale with modern distributed architectures.

The Core Concepts of Service Discovery

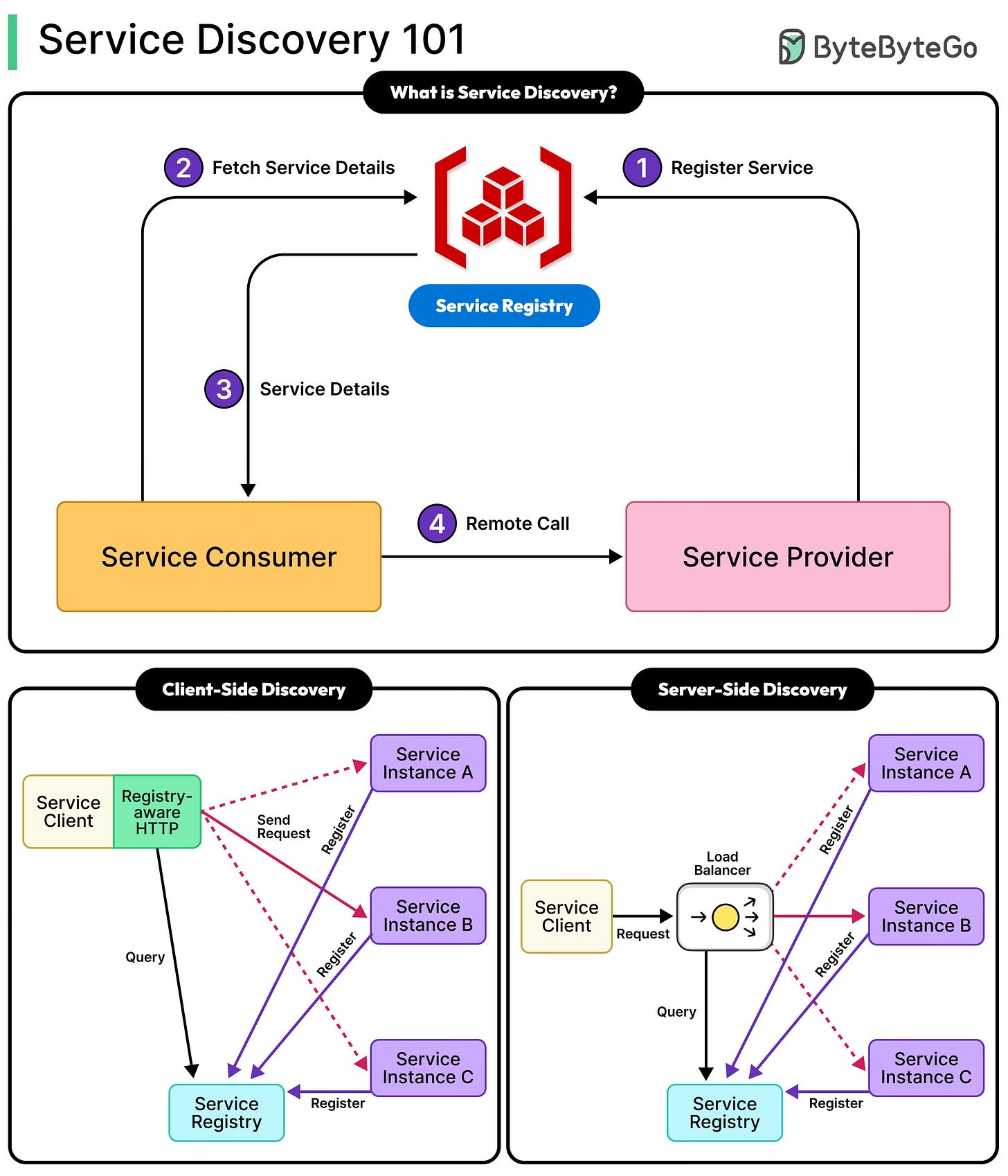

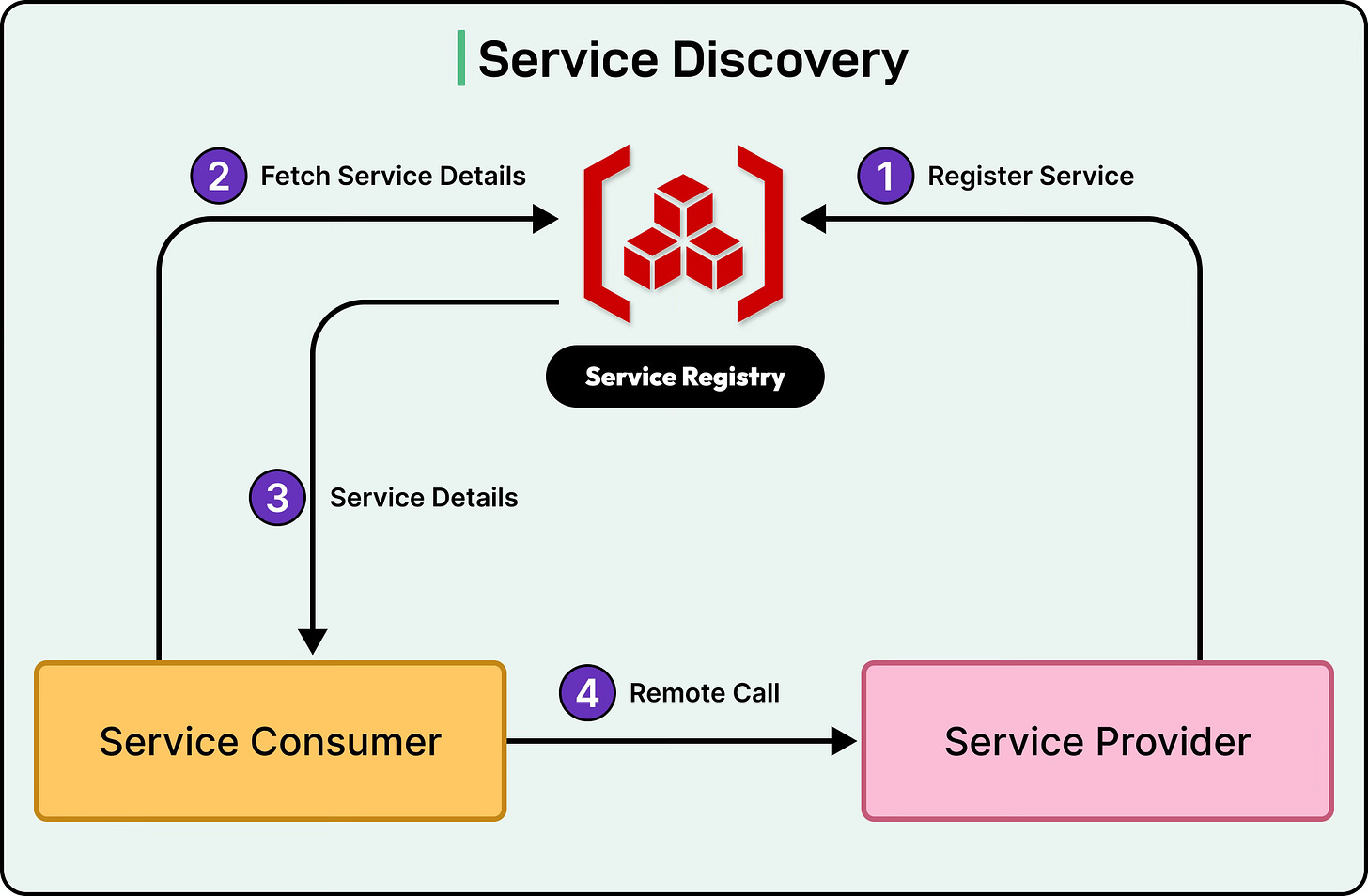

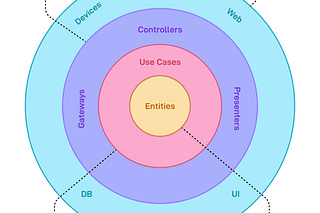

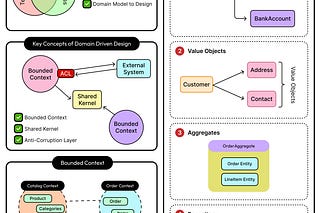

Service discovery solves the hardcoding problem through three fundamental components working together.

First, the Service Registry acts as a centralized database that maintains current information about all available services in the system. Think of it as a constantly updated directory that knows where every service is located at any given moment.

Second, Service Registration is the process by which services announce their presence to this registry when they start up. When a new Payment Service instance launches, it immediately tells the registry, “I’m available at this address and ready to handle requests.”

Third, Service Lookup enables services to query the registry to find other services they need to communicate with. When the Order Service needs to process a payment, it asks the registry for the current location of available Payment Service instances.

See the diagram below:

The lifecycle of a service instance reveals how these components work together in practice.

When a Payment Service instance starts on a new container, it first registers itself with the service registry, providing its IP address (10.0.2.15) and port (8080).

The registry adds this information to its database and begins monitoring the service’s health.

The Payment Service then sends regular heartbeat signals, typically every 10 to 30 seconds, confirming it’s still alive and operational.

The registry also performs active health checks, sending HTTP requests to a designated health endpoint to verify the service can actually handle traffic.

Throughout its lifetime, the Payment Service continues these heartbeats while serving requests.

If it becomes overloaded or encounters errors, it can update its status to “degraded” or “unhealthy,” signaling that traffic should be routed elsewhere. When the service prepares to shut down for maintenance or scaling down, it sends a deregistration message to the registry, which immediately removes it from the available instances list.

If a service crashes unexpectedly without deregistering, the registry detects the missing heartbeats and marks it as failed after a timeout period, preventing other services from sending requests to the dead instance.

The registry stores far more than simple network addresses.

Each service entry includes metadata such as version numbers (v2.1.3), environment tags (production, staging), capabilities (supports-refunds, accepts-EUR), and current health metrics (response time, error rate).

This rich metadata enables intelligent routing decisions. For instance, the Order Service can specifically request Payment Service instances that support a particular currency, or preferentially route to newer versions during a gradual rollout. The registry might track that certain instances are experiencing high latency and automatically deprioritize them, distributing load to healthier instances without any manual intervention.

Two Approaches for Service Discovery

There are two main approaches to handling service discovery: client-side and server-side. Let’s look at both in detail:

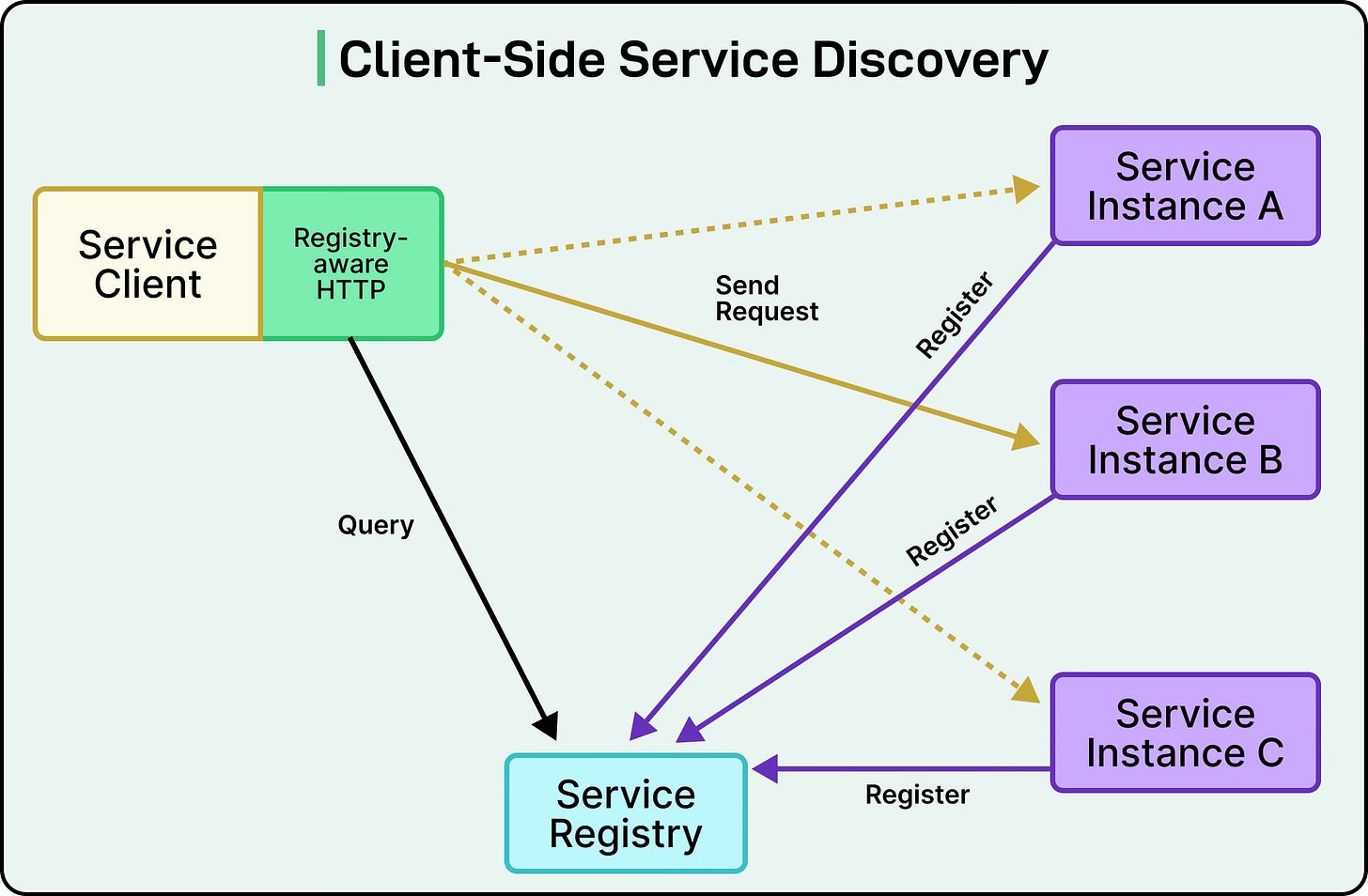

Client-Side Discovery

In client-side discovery, each service takes responsibility for finding and choosing which instance to call.

When the Order Service needs to process a payment, it directly queries the service registry for all available Payment Service instances.

The registry returns a list of healthy instances with their addresses and metadata.

The Order Service then applies its own load-balancing logic to select one instance, perhaps choosing the one with the lowest latency or using a round-robin approach, and makes a direct connection to that specific Payment Service instance.

See the diagram below that shows the concept of client-side discovery:

Netflix pioneered this approach at scale with its Eureka registry and Ribbon client-side load balancer.

Their architecture made sense because they operated at a massive scale, where even load balancers could become bottlenecks. By putting intelligence in the clients, they could implement sophisticated routing strategies. Services could make decisions based on real-time metrics, retry failed requests with different instances, and implement circuit breakers to avoid unhealthy instances. Since there’s no intermediary, requests go directly from service to service, minimizing latency.

However, client-side discovery introduces significant complexity.

Every service needs to include discovery logic, load balancing algorithms, health checking, and retry mechanisms. In organizations using multiple programming languages, this means maintaining discovery client libraries for Java, Python, Go, and any other language in use. Each library must implement the same features and behaviors, and keeping them synchronized becomes a constant challenge. A bug in the load-balancing logic needs to be fixed and deployed across every service in the system.

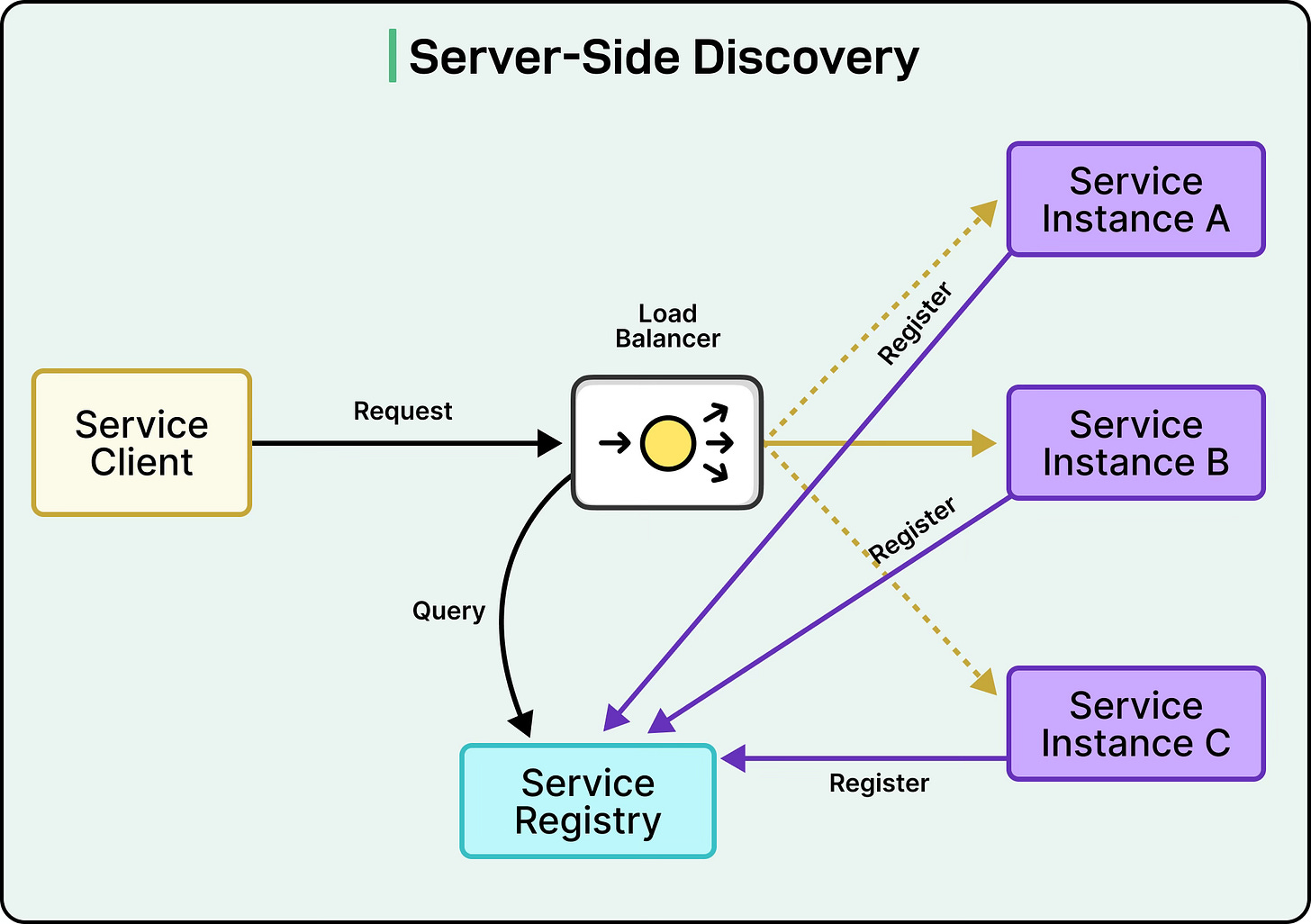

Server-Side Discovery

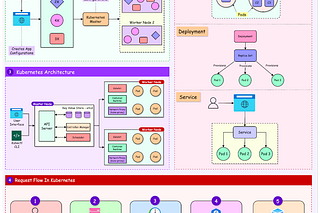

Server-side discovery moves the complexity away from individual services into a dedicated component like a load balancer or API gateway.

See the diagram below:

In this pattern, services simply send requests to a well-known, stable address.

When the Order Service needs the Payment Service, it sends its request to a load balancer at a fixed address like http://loadbalancer/payment-service.

The load balancer queries the service registry, chooses an appropriate instance, and forwards the request.

The Order Service remains blissfully unaware of how many Payment Service instances exist or where they’re located.

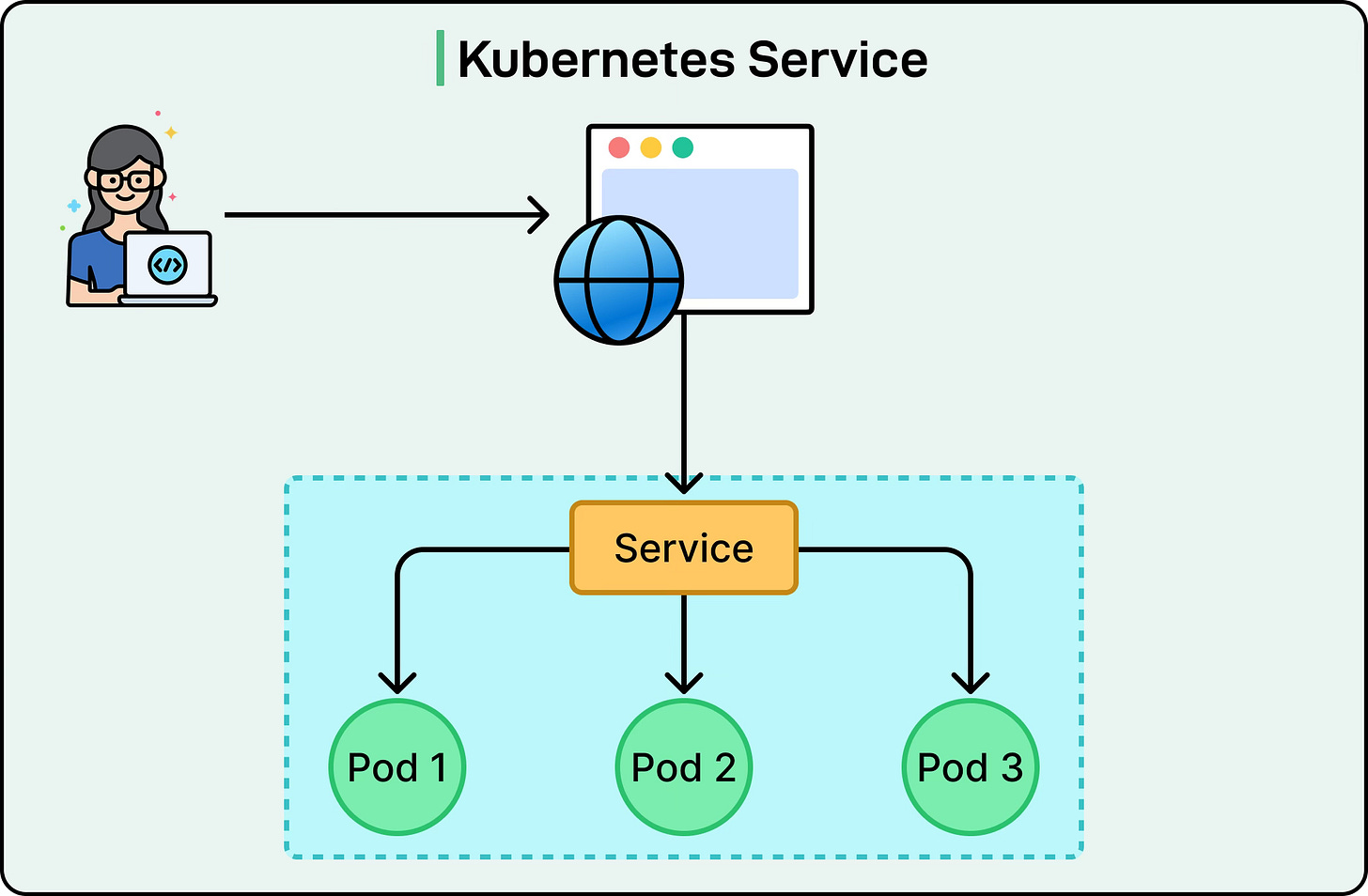

Kubernetes has popularized this approach with its built-in Service abstraction. When we create a Kubernetes Service, it gets a stable DNS name and a virtual IP address. Services simply call each other using these stable names, while Kubernetes handles the discovery, load balancing, and routing behind the scenes. This dramatically simplifies application code since services don’t need any discovery logic at all.

See the diagram below:

The main drawback is the additional network hop through the load balancer, which adds latency to every request. The load balancer itself can become a bottleneck or single point of failure if not properly scaled and made highly available. There’s also less flexibility for application-specific routing logic since all decisions are centralized in the load balancer.

The Modern Reality

Most organizations today adopt server-side discovery or sophisticated hybrid approaches that blur the traditional boundaries.

However, the rise of service meshes represents an evolution that combines the benefits of both patterns. These systems use sidecar proxies that run alongside each service.

From the application’s perspective, it looks like server-side discovery since they just call localhost, but the sidecar proxy handles discovery and load balancing locally, providing the performance benefits of client-side discovery without the application complexity.

Service Discovery at Scale

When services span multiple geographic regions, service discovery faces entirely new challenges.

Network latency between regions becomes a major concern. A request from US-East to Asia-Pacific might take 200 milliseconds just for the round trip, compared to under 1 millisecond within the same data center. If services in Asia need to query a service registry in the US for every discovery request, this latency gets added to every service interaction, making the system unbearably slow.

Network partitions between regions aren’t just theoretical possibilities but routine occurrences. Undersea cables get damaged, routing issues cause packet loss, and entire network links between continents can fail. When this happens, services in one region might be unable to reach the registry in another region, potentially making all services undiscoverable even though they’re running perfectly fine locally.

Federated Discovery

The solution involves running separate service registries in each region that share information.

Each region maintains its own registry cluster that primarily handles local services. Services in US-East register with the US-East registry, while services in Asia-Pacific register with their local registry. These regional registries then federate, selectively sharing information about services that should be discoverable globally.

Consider a global e-commerce platform. Order Services run in every region to serve local customers with low latency. These services register only with their regional registry and remain invisible to other regions. The Inventory Service, however, runs only in US-East, where the warehouse management system operates.

This service registers as “globally visible,” causing the US-East registry to replicate its information to registries in all other regions. When an Order Service in Asia-Pacific needs to check inventory, it queries its local registry, which returns the Inventory Service location in US-East from its replicated data.

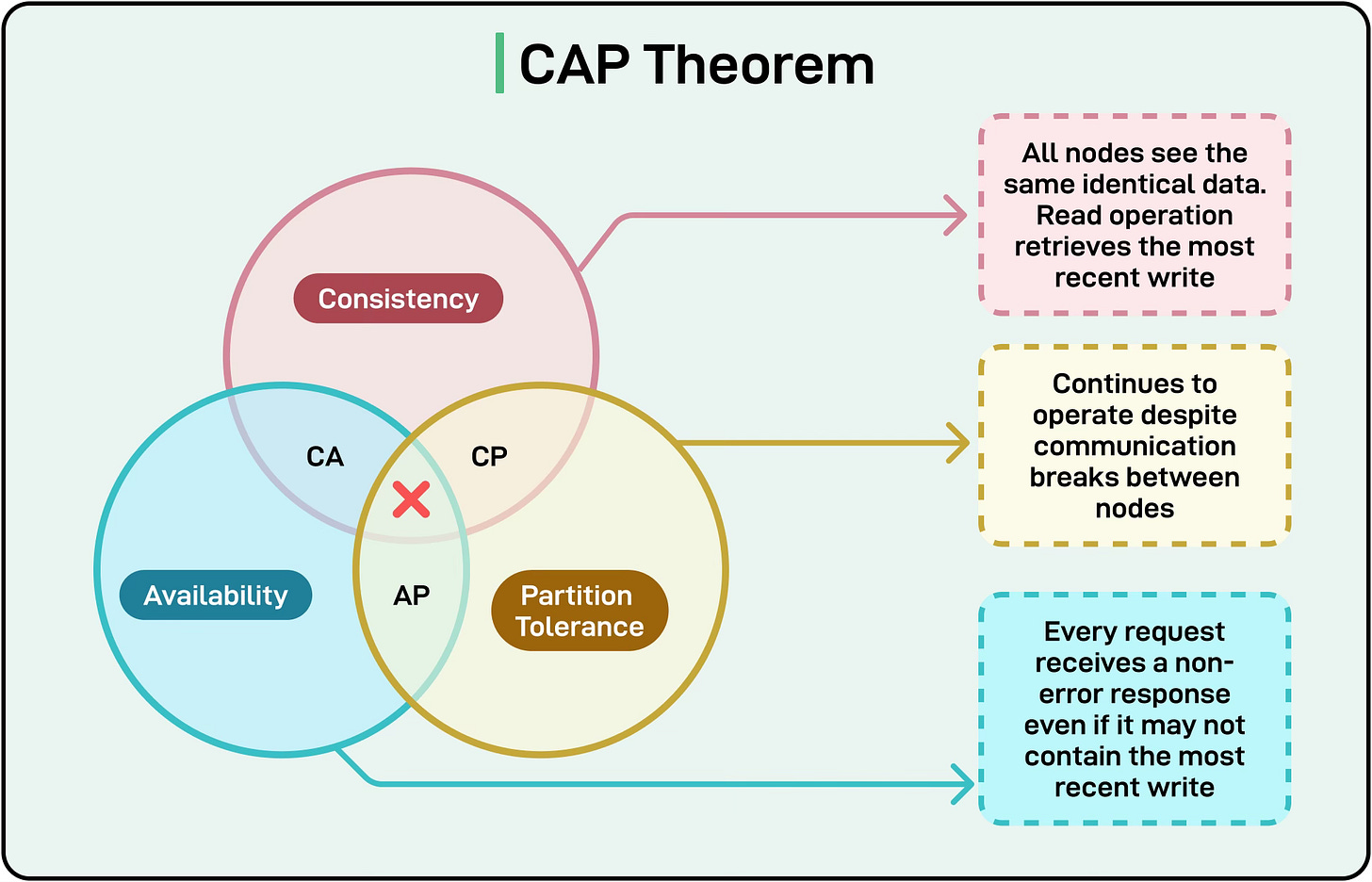

The CAP Theorem in Practice

In distributed systems, we cannot simultaneously guarantee Consistency (all registries have identical data), Availability (discovery always works), and Partition tolerance (handling network splits).

Multi-region service discovery typically chooses availability over strict consistency. When a new service registers in one region, it might take 30 seconds or even several minutes before other regions learn about it. This “eventual consistency” means different regions temporarily have different views of the global service topology.

In production, “eventual” typically means seconds for critical updates like health status changes, but potentially minutes for new service registrations.

This trade-off is acceptable because service topology doesn’t change rapidly in stable systems. It’s better for each region to continue operating with slightly outdated information than to stop working entirely when regions can’t communicate with each other.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at service discovery in detail.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Service discovery eliminates the need for hardcoded network addresses by providing a dynamic mechanism for services to find each other in distributed systems, similar to how a food delivery app tracks which restaurants are currently available and accepting orders.

Hardcoding IP addresses and ports fails in modern cloud environments because services constantly move between servers, auto-scale based on traffic, and run in ephemeral containers that can restart anywhere in the infrastructure.

The three core components of service discovery are the Service Registry (centralized database of service locations), Service Registration (how services announce themselves), and Service Lookup (how services find each other).

Services follow a complete lifecycle from registration at startup through sending regular heartbeats to confirm health, updating their status when degraded, and deregistering when shutting down gracefully or being marked as failed when heartbeats stop.

The registry stores rich metadata beyond IP addresses, including version numbers, capabilities, health metrics, and environment tags, enabling intelligent routing decisions like sending traffic only to instances that support specific features.

Client-side discovery gives services direct control over load balancing and routing decisions, but requires every service to implement discovery logic, creating complexity, especially in polyglot environments with multiple programming languages.

Server-side discovery simplifies services by moving discovery logic to load balancers or API gateways, though it adds an extra network hop and potential bottleneck, which is why Kubernetes and most modern platforms prefer this approach.

Multi-region service discovery must handle significant network latency between regions and routine network partitions that can isolate entire regions from each other.

Federated discovery solves multi-region challenges by running separate registries in each region that share information about global services, while keeping regional services local to minimize unnecessary cross-region traffic.

Production systems often choose eventual consistency over strict consistency in multi-region setups, accepting that different regions might have slightly different views of service topology for a few seconds or minutes in exchange for continued availability during network partitions.