When applications grow beyond a single server, they face the challenge of handling more users, more data, and more requests than one machine can manage.

This is where load balancers come in.

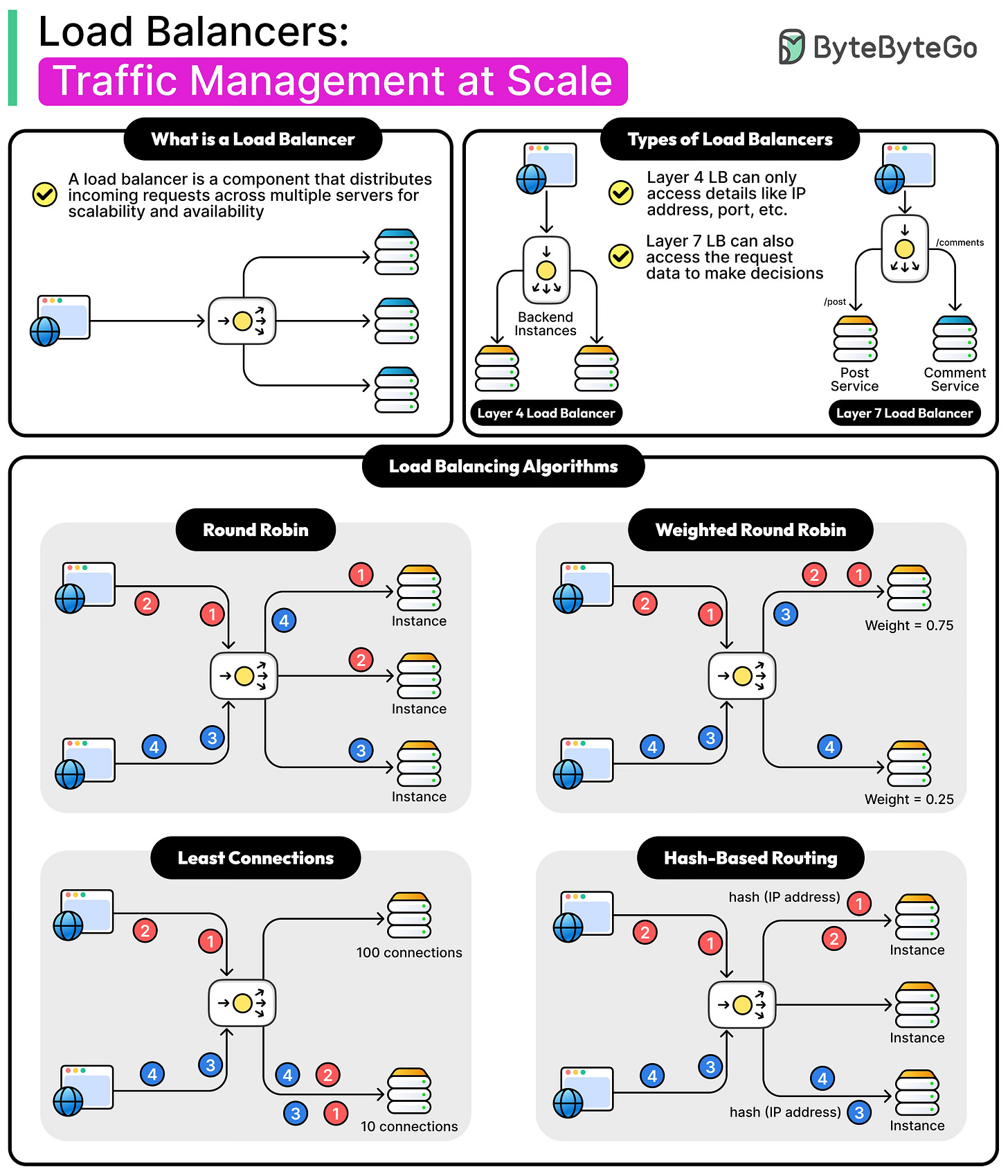

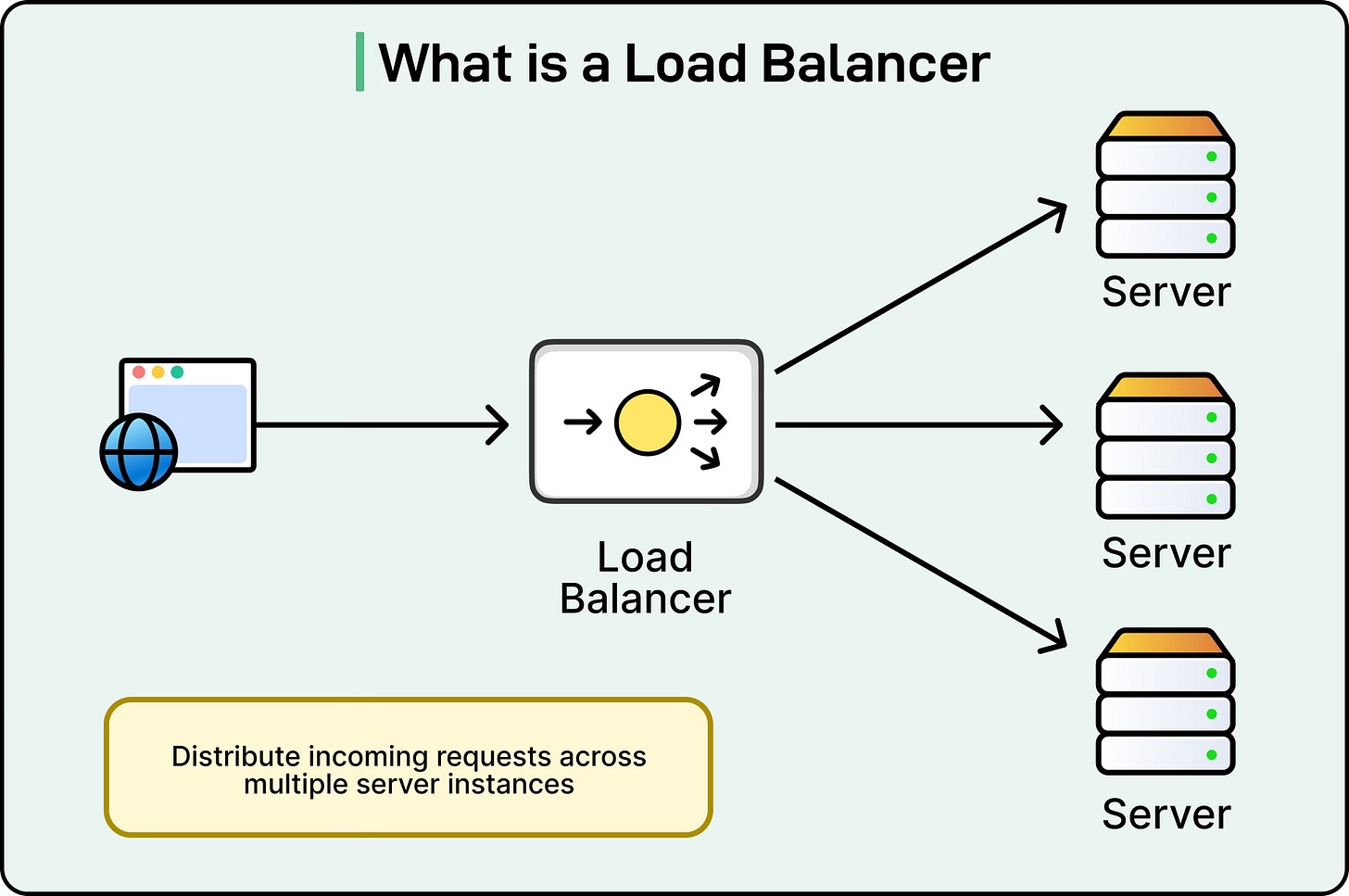

A load balancer is a system that sits between clients and servers and distributes incoming traffic across multiple backend servers. By doing this, it prevents any single server from being overloaded, ensuring that users experience smooth and reliable performance.

Load balancers are fundamental to modern distributed systems because they allow developers to scale applications horizontally by simply adding more servers to a pool. They also increase reliability by detecting server failures and automatically rerouting traffic to healthy machines.

In effect, load balancers improve both availability and scalability, two of the most critical qualities of any large-scale system.

In this article, we will learn how load balancers work internally, the differences between load balancing at the transport and application layers, and the common algorithms that power traffic distribution in real-world systems.

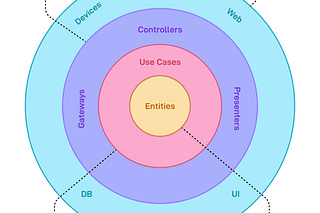

The Role of Load Balancers

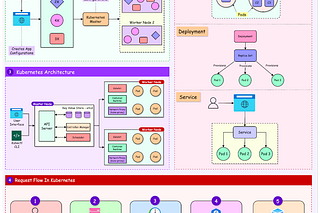

In a typical system architecture, a load balancer acts as the central entry point for all client requests. Instead of clients connecting directly to backend servers, they connect to the load balancer, which then forwards the request to one of the servers in the pool.

See the diagram below:

This setup hides the details of the backend servers from clients, making the system more flexible and secure. For example, if new servers are added or old ones are removed, clients do not need to be aware of these changes. They continue to interact with a single endpoint while the load balancer takes care of distributing traffic behind the scenes.

Since the load balancer sits between clients and servers, it plays a critical role in maintaining fault tolerance. If one of the backend servers goes down, the load balancer can detect the failure through health checks and immediately stop sending traffic to that server. This prevents users from seeing errors and ensures that only healthy servers handle requests.

In many systems, load balancers are also configured for failover, which means that if an entire data center or server pool fails, traffic can be rerouted to another region or cluster without client-side changes.

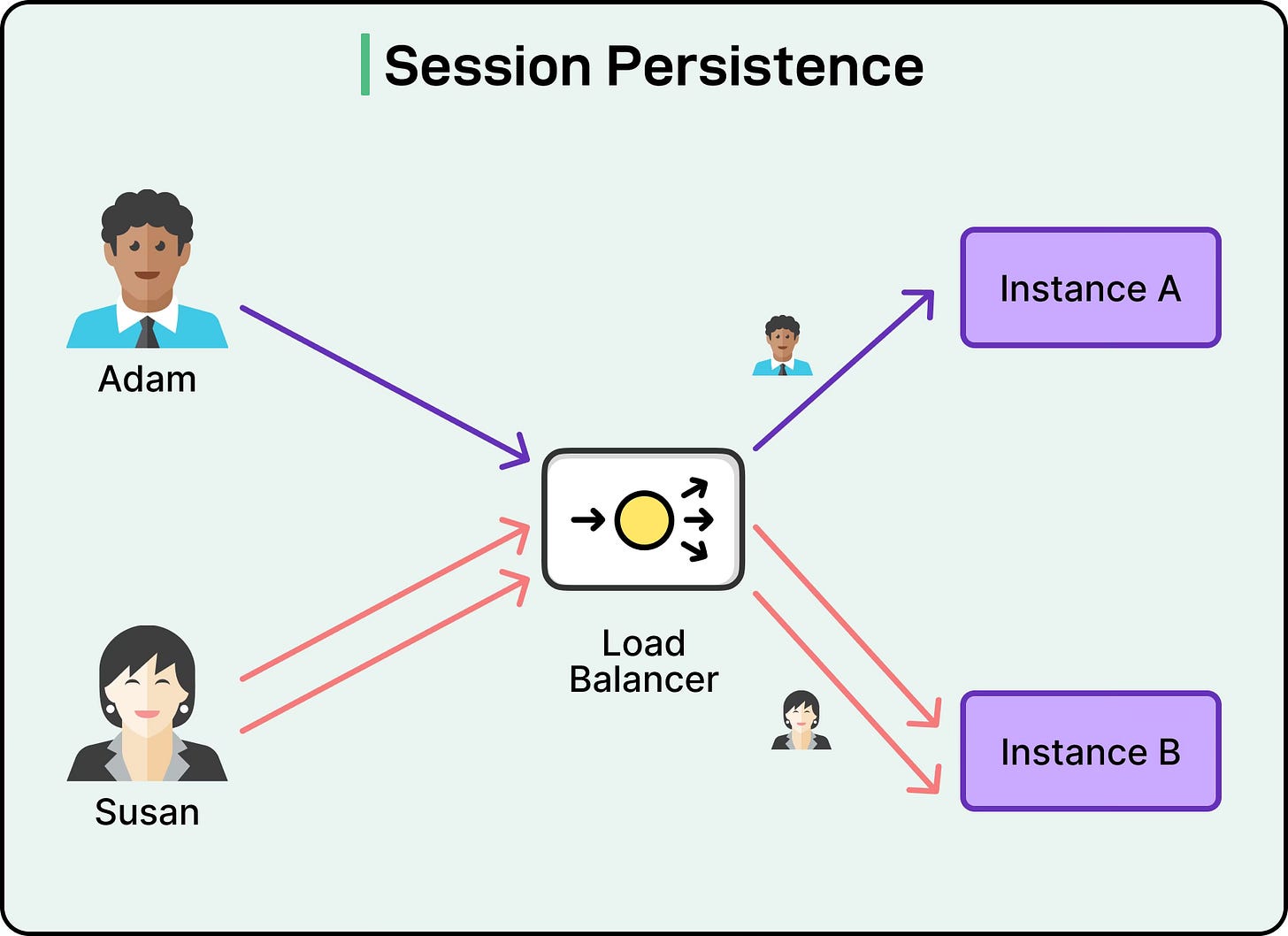

Another important responsibility of load balancers is session persistence. Many applications need to ensure that a user continues interacting with the same server across multiple requests. The load balancer can achieve this by using techniques such as cookies or hashing based on client IP addresses to consistently send requests to the same backend instance. Without this mechanism, certain user sessions might break if traffic were routed randomly each time.

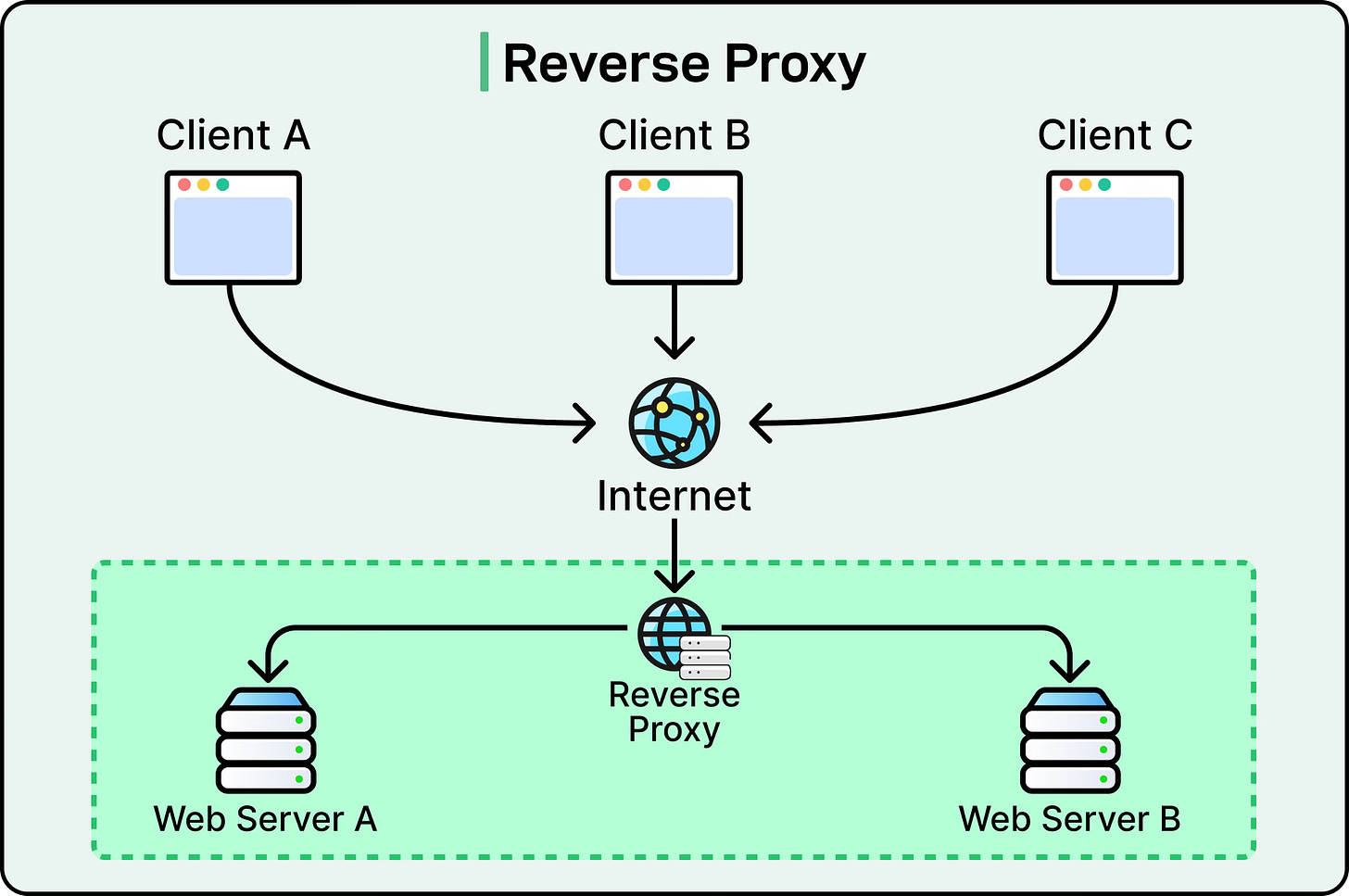

Overall, the load balancer acts as a reverse proxy, simplifying how clients interact with complex distributed systems.

Internal Working of a Load Balancer

At a high level, a load balancer looks simple: it receives a client request, decides which backend server should handle it, and forwards the traffic.

In practice, the internals of a load balancer are highly sophisticated. They involve careful management of network packets, connection states, encryption, and health monitoring. Understanding how this works step by step helps reveal why load balancers are such critical infrastructure in modern distributed systems.

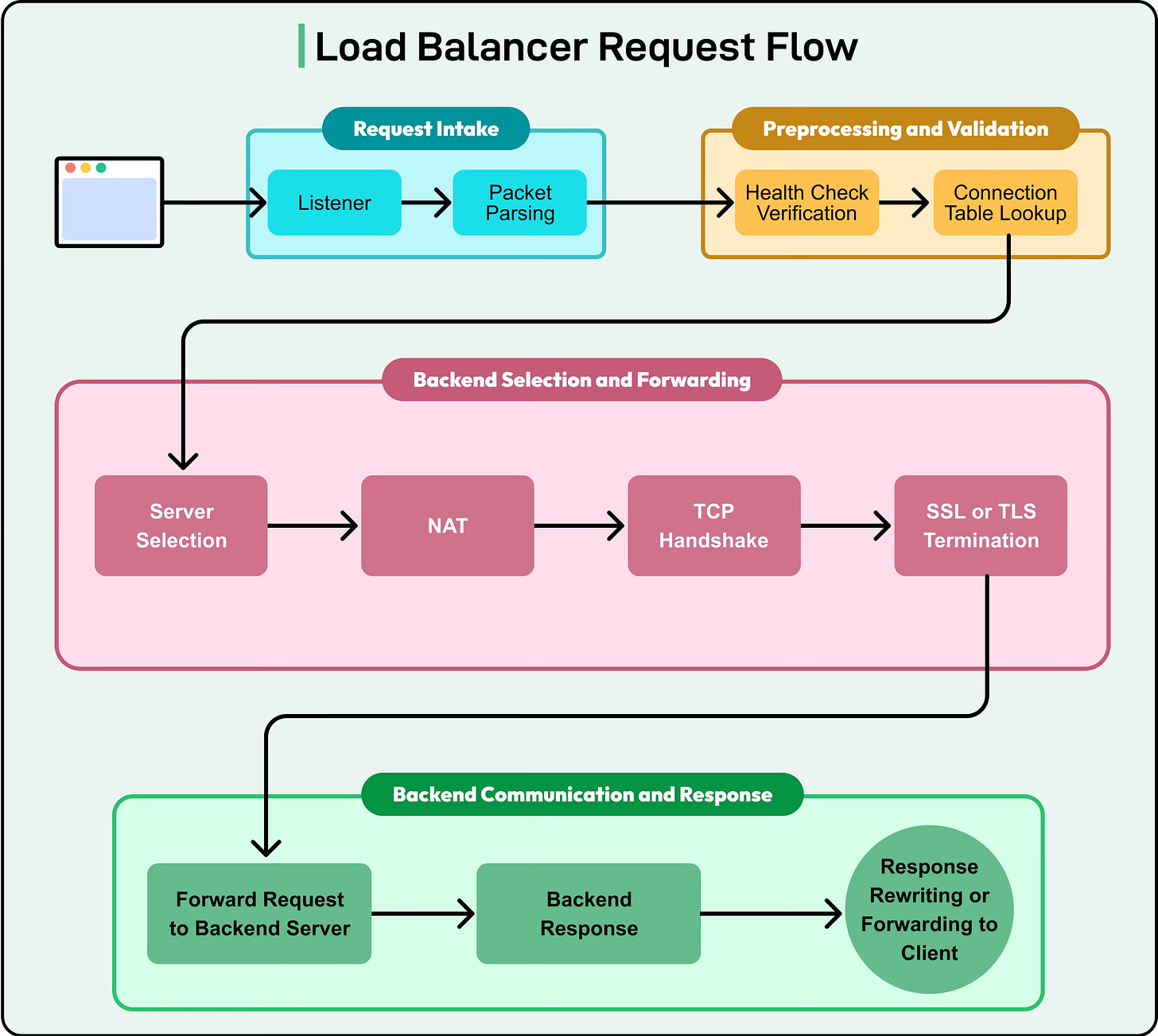

See the diagram below for a high-level overview:

When a client request arrives at the load balancer, the following sequence typically occurs with variations that may happen across different providers:

Listening for Requests: The load balancer first opens a listener socket on a specific IP address and port, such as 0.0.0.0:80 for HTTP or 0.0.0.0:443 for HTTPS. This listener is responsible for receiving all incoming connections from clients.

Packet Parsing and Inspection: Once a connection is established, the load balancer parses the incoming packet headers. At Layer 4, this may only include examining the source IP, destination IP, and TCP or UDP port. At Layer 7, it can go deeper into the packet to inspect HTTP headers, cookies, URLs, or even payload data. This inspection allows the load balancer to apply routing rules based on configured policies. More on this in a later section.

Connection Table Management: The load balancer maintains an internal connection table or session table. This maps each client connection to a backend server. For example, if a client at 192.168.1.10 opens a TCP connection on port 443, the load balancer records which backend server was chosen for that session. This mapping ensures consistency in forwarding subsequent packets of the same connection. Also, this table can track timeouts, retransmissions, and protocol states. Such details matter in long-lived or idle connections.

Server Selection Using Algorithms: Once the packet is inspected, the load balancer applies its configured load balancing algorithm (such as round robin, least connections, etc.) to determine which backend server will handle the request. For applications that require session persistence, the algorithm may be overridden by sticky session rules.

NAT and Packet Rewriting: Before forwarding the packet to the backend server, the load balancer often performs Network Address Translation (NAT). This involves rewriting the packet headers so that the backend server sees the source IP as the load balancer itself, rather than the original client. When the server responds, the load balancer rewrites the response headers so the client believes it is communicating directly with the server. NAT is critical for seamless proxying and security.

TCP Handshake Management: For protocols like TCP, the load balancer may handle the entire three-way handshake with the client before initiating a new connection to the backend. This ensures that if the chosen server is unavailable, the load balancer can retry with a different server without the client being aware of the failure.

SSL/TLS Termination: Many modern load balancers perform SSL or TLS termination. This means they decrypt incoming HTTPS traffic at the load balancer itself. The decrypted traffic can then be inspected for Layer 7 routing decisions, logged for monitoring, or even re-encrypted before forwarding to the backend servers. Offloading encryption to the load balancer reduces CPU usage on backend servers and centralizes certificate management.

Forwarding and Response Handling: Once a backend server is selected and the necessary transformations are applied, the packet is forwarded. The load balancer continues to track the connection so that when the server responds, it can rewrite and forward the response back to the correct client.

Health Checks and Server Monitoring

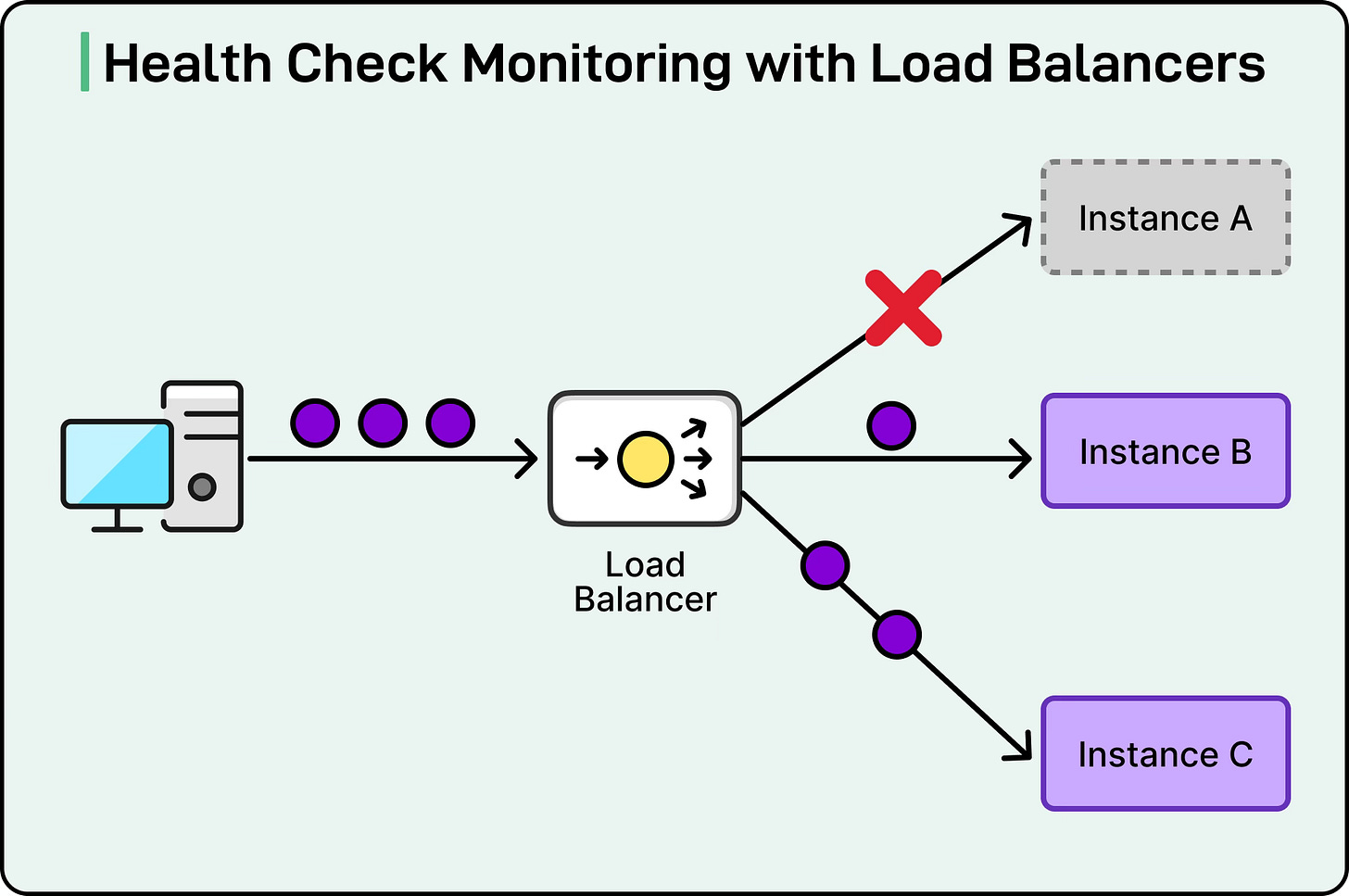

Load balancers must constantly know the health of backend servers. They achieve this by performing periodic health checks as follows:

TCP checks simply attempt to open a connection to the server.

HTTP checks send an HTTP request (for example, GET /health) and verify the response code.

Custom checks may run scripts or check specific application-level behaviors.

If a server fails health checks, it is temporarily removed from the rotation. Once it passes checks again, it is added back. This mechanism ensures that clients are never routed to unhealthy servers.

See the diagram below:

State Maintenance

Maintaining a state table is one of the most critical tasks of a load balancer.

Every active connection must be tracked so that packets are consistently routed to the same backend. This is especially important for TCP, where each connection is defined by a tuple of source IP, source port, destination IP, and destination port.

The state table records:

Which server a client is bound to.

Connection start and end times.

Session stickiness details if enabled.

Timeout values to clean up stale sessions.

Keepalives and Connection Reuse

To optimize performance, load balancers often maintain persistent connections, known as keepalives, with backend servers.

Instead of opening a new TCP connection for every request, the load balancer can reuse an existing connection.

This reduces latency, saves CPU cycles, and avoids excessive connection setup overhead. For protocols like HTTP/2, multiplexing allows multiple streams to share a single connection, further increasing efficiency.

Layer 4 Vs Layer 7 Load Balancing

Load balancers can make their routing decisions at different layers of the OSI model, most commonly at Layer 4 (the transport layer) or at Layer 7 (the application layer).

The choice between the two has a big impact on performance, flexibility, and complexity. Let’s look at both in detail:

Layer 4 Load Balancing

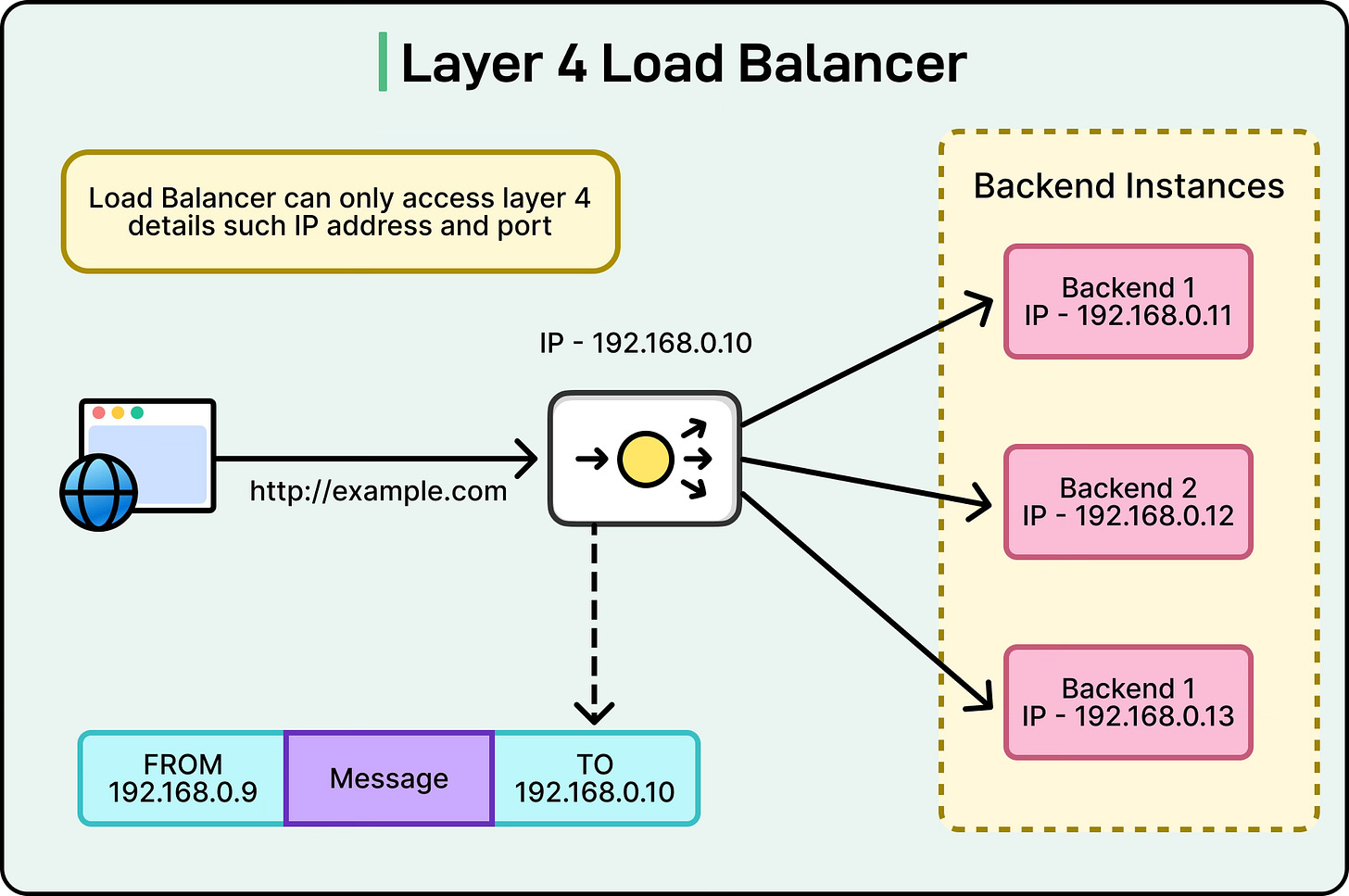

Layer 4 load balancing works at the transport layer of the OSI model. At this level, the load balancer only looks at information available in the TCP or UDP headers, such as the source IP address, destination IP address, source port, and destination port. Based on these values, it decides which backend server should handle the request.

See the diagram below:

For example, if a client connects to a web application over TCP port 443 (HTTPS), the Layer 4 load balancer will receive the connection, check its algorithm (like round robin or least connections), and forward the packets to a chosen server. It does not need to inspect the content of the packets. This makes L4 load balancing very fast and efficient because the load balancer only needs to deal with network and transport layer headers, not the payload.

Common techniques used in L4 load balancing include:

IP Hashing: Using the client IP to always route the connection to the same server.

Port-based Routing: Sending requests to different backend groups based on port numbers.

Simple Algorithms: Applying round robin or least connections without analyzing application-level details.

Since it does not look into the application data, Layer 4 load balancing is often protocol-agnostic and can work equally well for HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, SMTP, or custom TCP/UDP-based applications. The trade-off is that it lacks the fine-grained control of application-aware routing.

Layer 7 Load Balancing

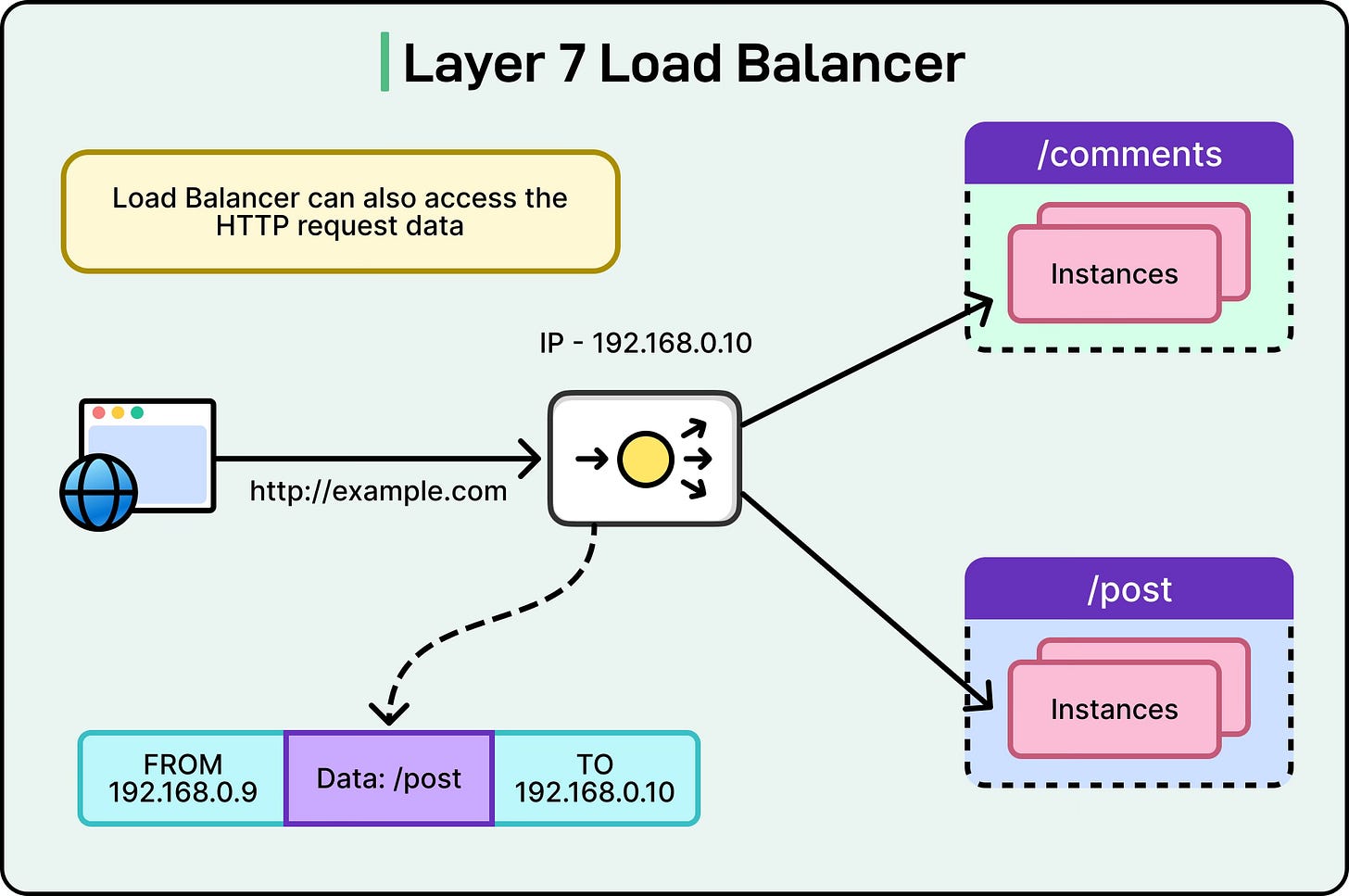

Layer 7 load balancing operates at the application layer, which means it can inspect the actual content of the requests. Instead of just looking at IPs and ports, it can analyze HTTP headers, cookies, request URLs, query strings, and even the body of the request. This gives it much more power to make routing decisions based on application-specific logic.

For instance, a Layer 7 load balancer can:

Route requests for /images/ to a set of servers optimized for static content and /api/ requests to servers running application logic.

Send traffic to different backend pools based on the hostname, which is useful for serving multiple domains or microservices from the same load balancer.

Use cookies to maintain sticky sessions by ensuring a user is always directed to the same server for the duration of their session.

Perform advanced functions like header rewriting, SSL termination, and inspection for security policies.

See the diagram below that shows a Layer 7 load balancing example to route requests to different API services:

Layer 7 load balancers essentially act as “application proxies”. They terminate client connections, parse the request, apply rules, and then open a new connection to the selected backend server. This additional work introduces some overhead compared to Layer 4 but provides much greater flexibility.

Trade-offs Between Layer 4 and Layer 7

The choice between Layer 4 and Layer 7 balancing depends on the system’s requirements.

Performance: Layer 4 is faster because it only deals with TCP/UDP headers. It has lower latency and higher throughput, making it ideal for high-performance systems or workloads that do not need application-aware routing. However, with the advancement in infrastructure, the difference has become quite negligible over the years.

Flexibility: Layer 7 offers far more control because it can understand application data. It can perform routing based on URLs, hostnames, and cookies, which is essential for microservices, APIs, or complex web applications.

Complexity: Layer 4 is simpler to configure and maintain, while Layer 7 requires more detailed configuration and may need additional resources like SSL certificates or application-specific rules.

Use Cases: Layer 4 is often used for raw TCP or UDP applications, gaming servers, VoIP, or simple load distribution where content does not matter. Layer 7 is used for web applications, microservices, API gateways, and environments that require fine-grained traffic control.

In many modern architectures, both types are used together.

A Layer 4 load balancer may handle raw traffic distribution across data centers or availability zones, while Layer 7 load balancers inside each region manage application-level routing among services.

Most Popular Load Balancing Algorithms

The effectiveness of a load balancer depends not just on its ability to receive and forward requests, but also on how it decides which backend server should handle each request.

This decision-making process is governed by load-balancing algorithms. Different algorithms are suited for different workloads, traffic patterns, and server environments.

Below are the most widely used ones, explained in detail:

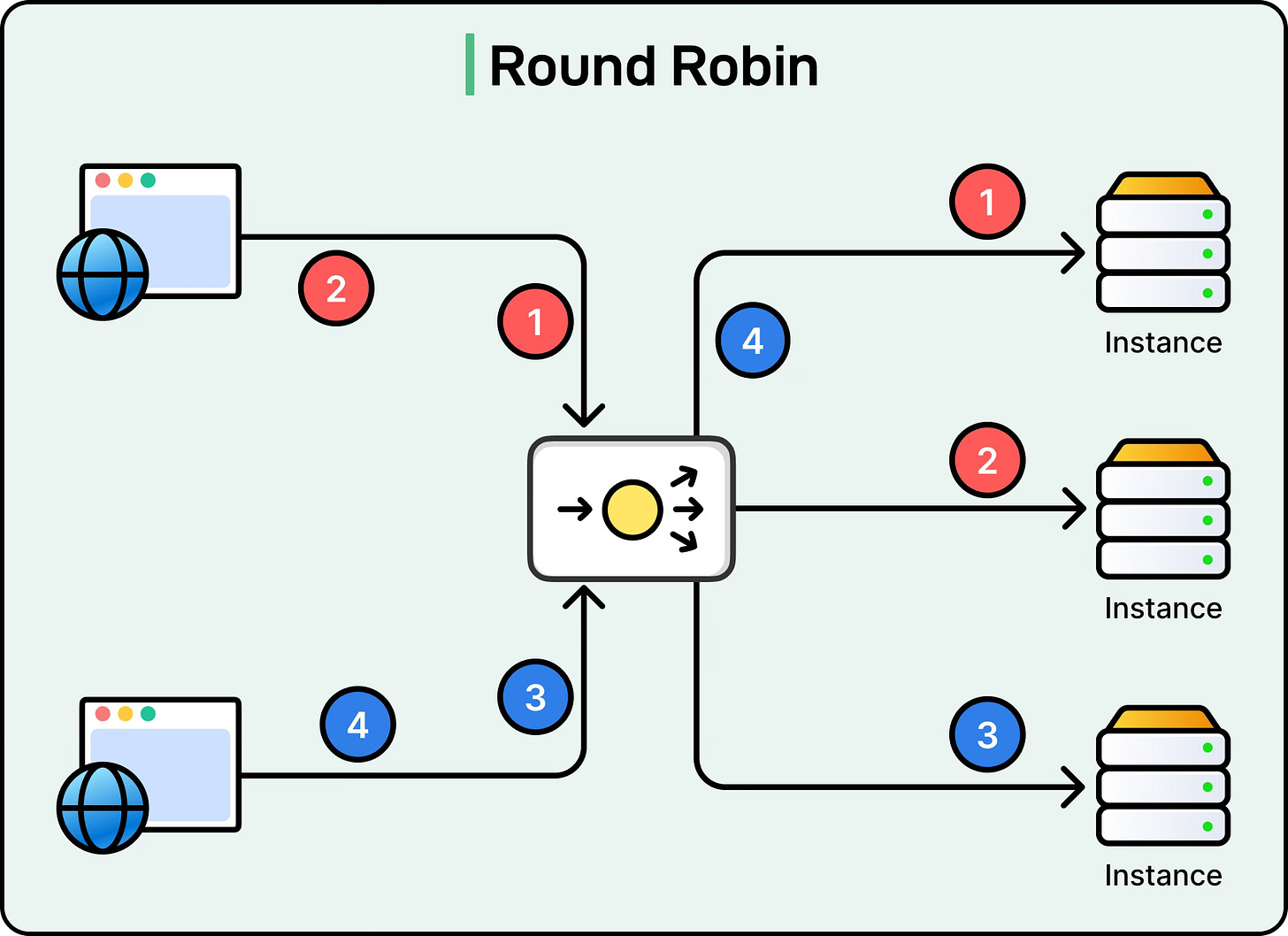

Round Robin

Round Robin is the simplest algorithm. The load balancer cycles through the list of available servers in order and assigns each new request to the next server in line. When it reaches the end of the list, it starts over from the beginning.

See the diagram below:

For example, if there are three server instances (A, B, C), the requests will be distributed as A followed by B followed by C, and then back to A, and so on. This approach works well when all servers have roughly the same capacity and the requests are similar in size.

However, if one request is computationally heavy and another is light, the distribution can become uneven because Round Robin does not account for workload differences.

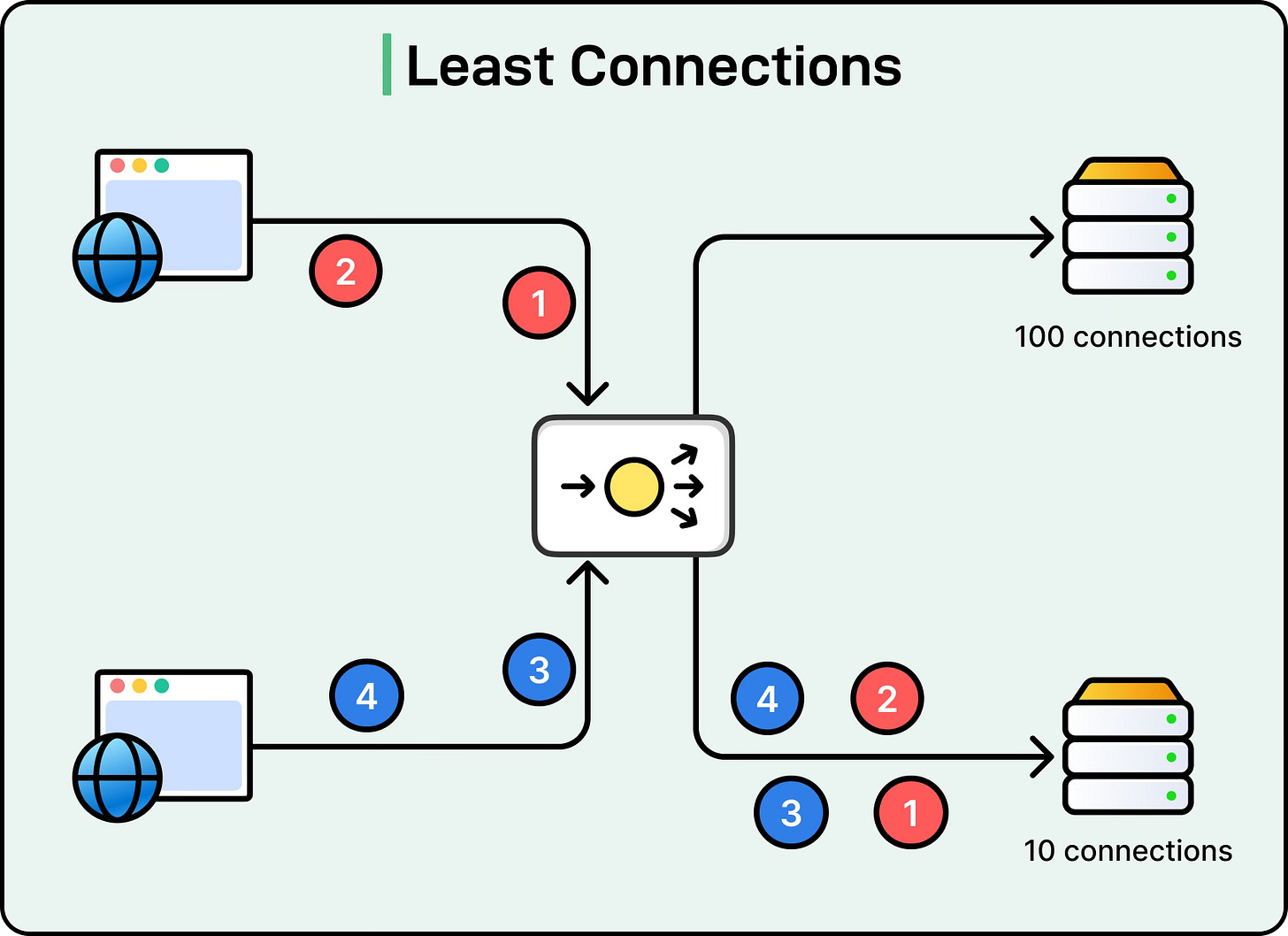

Least Connections

The Least Connections algorithm routes a new request to the server with the fewest active connections. This method is more dynamic than Round Robin because it adapts to the actual load on each server.

For instance, if Server A currently has 100 active connections, and Server B has 10, the next request will go to Server B. This algorithm is particularly useful for long-lived connections such as database queries or streaming applications, where connection counts can vary widely between servers.

The limitation of this approach is that it assumes all connections have equal cost, which may not be true if some connections are lightweight while others are heavy.

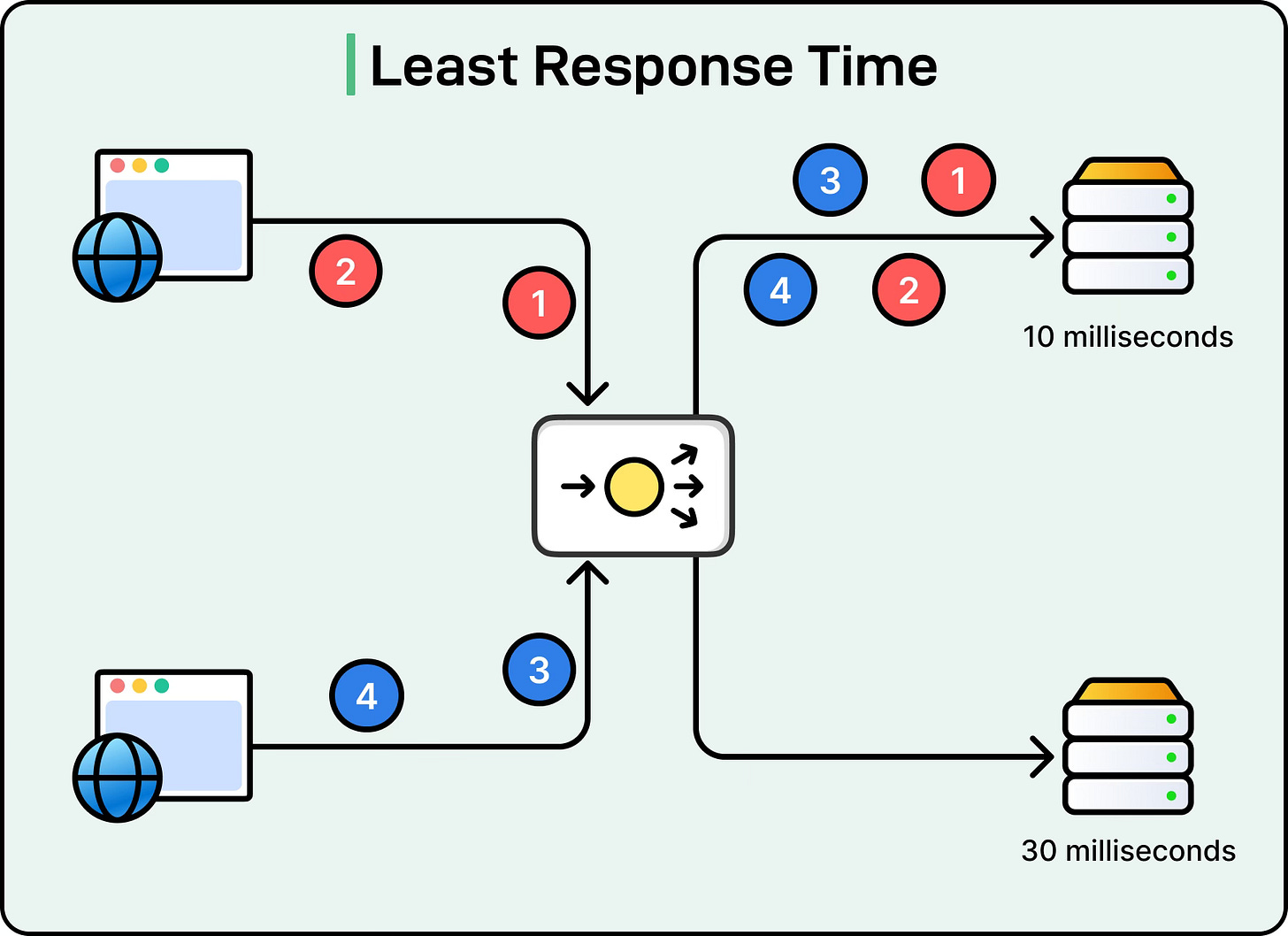

Least Response Time

Least Response Time improves on Least Connections by also considering server latency.

The algorithm looks at two factors: the number of active connections on a server and the average response time. A server with fewer connections and faster responses is preferred.

See the diagram below:

This is especially useful for web applications or APIs where responsiveness is critical. If Server A has low latency but more connections and Server B has high latency but fewer connections, the load balancer will favor Server A as long as its response times remain better. The challenge here is that measuring response times requires constant monitoring and metrics collection, which introduces some overhead.

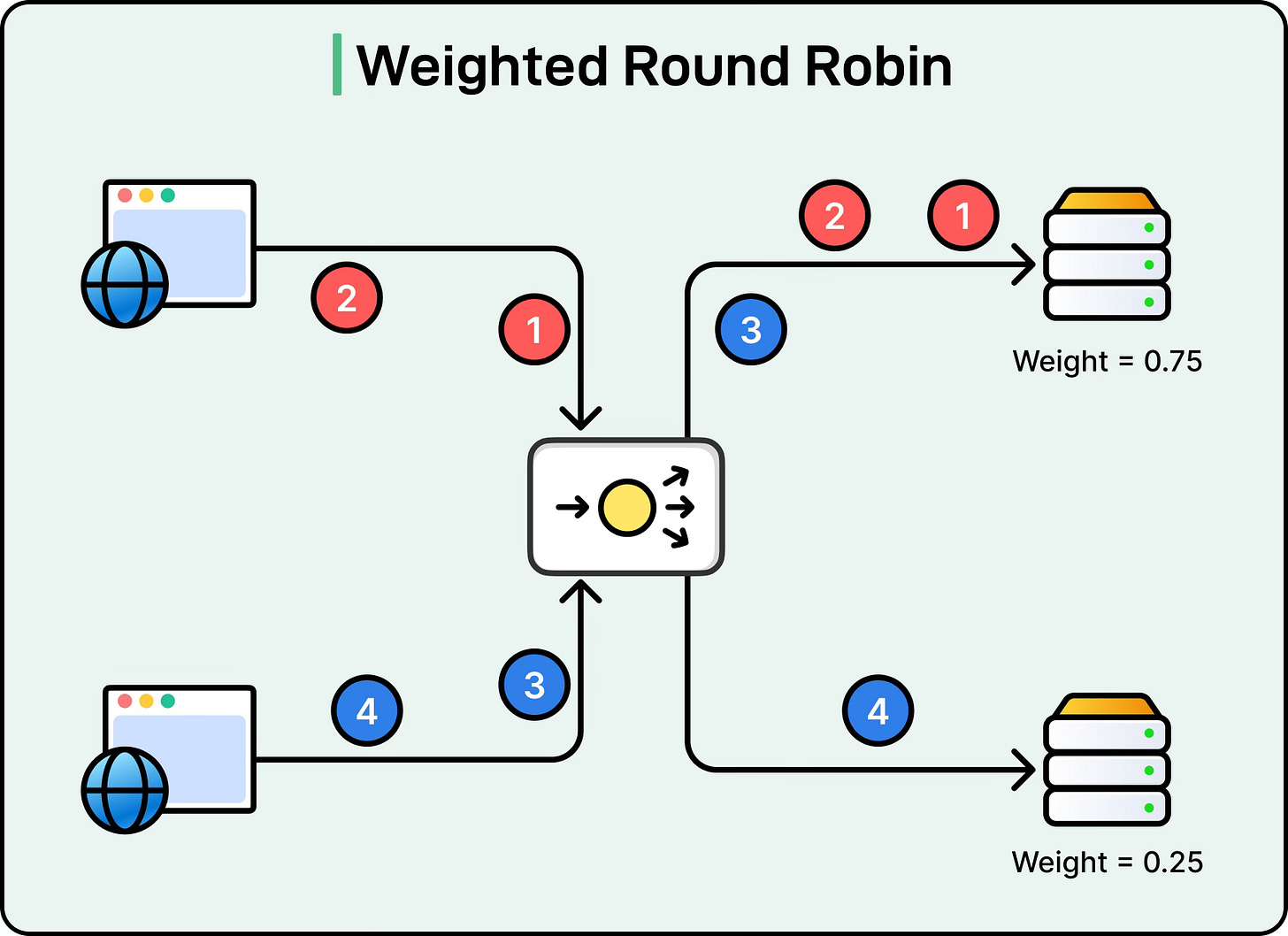

Weighted Round Robin

Weighted Round Robin is an extension of Round Robin that accounts for servers with different capacities. Each server is assigned a weight based on its relative processing power or resources. Servers with higher weights receive more requests in proportion to their capacity.

For example, if Server A has a weight of 3 and Server B has a weight of 1, then out of every four requests, Server A will receive three while Server B receives one. See the diagram below:

This algorithm is ideal for clusters where servers have heterogeneous hardware. However, weights must be carefully tuned to reflect actual server capabilities.

Weighted Least Connections

Weighted Least Connections combines the dynamic nature of Least Connections with the fairness of weighting. Here, each server has a weight, and the load balancer divides the number of active connections by the server’s weight to decide where the next request goes.

For instance, if Server A has a weight of 2 and 4 active connections, and Server B has a weight of 1 and 2 active connections, the effective load on Server A is 2 (4/2) while Server B’s effective load is also 2 (2/1). In this case, both are equally loaded. This method is very effective in mixed environments where both connection counts and server capacities vary.

Random Choice

As the name suggests, Random Choice selects a backend server at random for each request. While this may sound naive, it works surprisingly well when there are many servers and requests are short-lived, since random distribution tends to balance out statistically.

However, randomness can lead to uneven load distribution in smaller clusters or for workloads where request sizes vary significantly. It is rarely used as the primary algorithm, but can be combined with others for simplicity in certain scenarios.

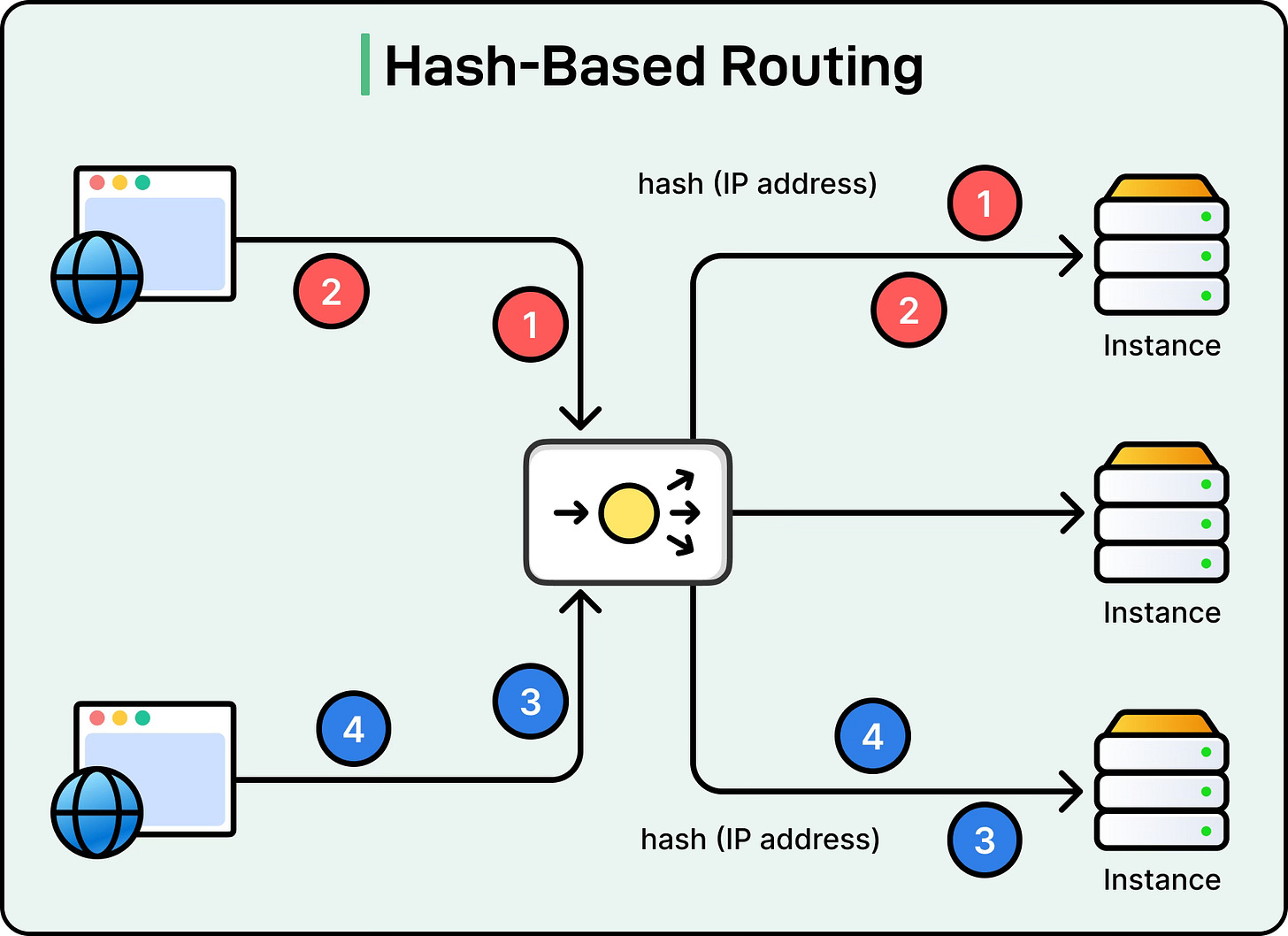

Hash-Based Routing

Hash-based routing uses a hashing function to map a client or request attribute to a specific server.

The most common attribute is the client’s IP address, but other values like session IDs, cookies, or URLs can also be used. The idea is that the same client or session always maps to the same server, ensuring session persistence.

A more advanced form of this is consistent hashing, which is widely used in distributed systems and caching layers. In consistent hashing, servers are placed on a logical ring, and client requests are hashed to positions on the ring. The request is routed to the nearest server on the ring. This minimizes reassignments when servers are added or removed, making it efficient for sticky sessions and distributed data storage.

The trade-off is that hash-based routing can create uneven load if the hash function or client distribution is skewed. To address this, consistent hashing often uses techniques like virtual nodes to balance the load better.

Power of Two Choices

The Power of Two Choices algorithm is a clever compromise between randomness and fairness. Instead of picking a single server at random, the load balancer randomly selects two servers and assigns the request to the one with fewer active connections.

This simple modification significantly improves load distribution compared to pure randomness while keeping the overhead minimal. It provides a good balance between efficiency and fairness, especially in large-scale distributed environments.

Summary

In this article, we’ve looked at how load balancers work internally, the differences between load balancing at the transport and application layers, and the common algorithms that power traffic distribution in real-world systems.

Here are the key learning points in brief:

Load balancers act as the central traffic managers in distributed systems, preventing servers from being overloaded and ensuring smooth user experiences.

They sit between clients and servers as reverse proxies, masking backend details, rerouting around failures, and enabling features like session persistence.

At Layer 4, load balancers operate at the transport layer, routing based on IP addresses and ports, offering speed and efficiency without application awareness.

At Layer 7, they operate at the application layer, inspecting HTTP headers, cookies, and URLs to make fine-grained routing decisions with greater flexibility but added complexity.

Core load balancing algorithms include Round Robin for simple distribution, Least Connections for dynamic balancing, and Least Response Time for latency-sensitive workloads.

Weighted variants of Round Robin and Least Connections account for heterogeneous server capacities, while Random Choice, Hash-based routing, and Power of Two Choices provide alternatives for specialized needs.

Internally, a load balancer handles packet flow through listening, packet parsing, connection table management, algorithmic server selection, NAT translation, TCP handshake handling, SSL termination, and response forwarding.

It maintains state tables for mapping client connections to backend servers, performs health checks to ensure traffic only goes to healthy nodes, and uses keepalives to optimize connection reuse.

Load balancers can run in proxy mode for maximum control or in direct server return mode for high-performance scenarios with less flexibility.